Opioid prescription policies may hurt those in chronic pain

Guidelines aim to prevent opioid-related deaths by making it more challenging to get prescriptions, but they can also block access for those who desperately need them.

Tinu Abayomi-Paul works as a writer and activist, plus one unwanted job: Trying to fill her opioid prescription. She says that some pharmacists laugh and tell her that no one needs the amount of pain medication that she is seeking. Another pharmacist near her home in Venus, Tex., refused to fill more than seven days of a 30-day prescription.

To get a new prescription—partially filled opioid prescriptions can’t be dispensed later—Abayomi-Paul needed to return to her doctor’s office. But without her medication, she was having too much pain to travel there, much less return to the pharmacy. She rationed out the pills over several weeks, an agonizing compromise that left her unable to work, interact with her children, sleep restfully, or leave the house. “Don’t I deserve to do more than survive?” she says.

Abayomi-Paul’s pain results from a degenerative spine disorder, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and more than a dozen other diagnoses and disabilities. She is part of a growing group of people with chronic pain who have been negatively impacted by the fallout from efforts to prevent opioid overdose deaths.

Guidelines for dispensing these pills are complicated because many opioids, like codeine, oxycodone, and morphine, are prescribed legally for pain. Yet, deaths from opioids have increased rapidly since 1999 and become a national emergency. Many of them, such as heroin, are used illegally. The CDC identified three surges in opioid use: an increase in opioid prescriptions in the ‘90s, a surge of heroin around 2010, and an influx of fentanyl and other powerful synthetic opioids in 2013.

As overdose deaths grew, so did public calls to address them, prompting the CDC to change its prescription guidelines in 2016. The new guidelines suggested limiting medication for acute pain to a seven-day supply, capping daily doses of morphine, and other restrictions. Some statistics suggest that these policies have worked; from 2016 to 2019, prescriptions for opiates fell 44 percent. Physicians also started progressively lowering opioid doses for patients, a practice called tapering. A study tracking nearly 100,000 Medicare subscribers on opioids found that about 13 percent of patients were tapering in 2012, and that number increased to about 23 percent by 2017.

But some physicians may be too aggressive with this tapering strategy. About one in four people had doses reduced by more than 10 percent per week, a rate faster than the CDC recommends. The approach left people like Abayomi-Paul without the medication they needed. Every year, Abayomi-Paul says, her prescriptions are harder to fill. David Brushwood, a pharmacy professor who specializes in policy and outcomes at the University of Florida in Gainesville, says opioid dosing isn’t one-size-fits-all. “Patients need to be taken care of individually, not based on what some government agency says they need,” he says.

‘This is not survivable’

Health policy and disability rights attorney Erin Gilmer advocated for people with pain, using her own experience with chronic pain and a host of medical conditions as a guidepost. She launched an advocacy website, Healthcare as a Human Right, and shared her struggles on Twitter: “This pain is more than anything I've endured before and I've already been through too much. Yet because it's not simply identified no one believes it's as bad as it is. This is not survivable.”

When her pain dramatically worsened midway through 2021, Gilmer’s posts grew ominous: “I keep thinking it can't possibly get worse but somehow every day is worse than the last.”

The CDC revised its guidelines in 2022 after criticisms that people with chronic pain were being undertreated, enduring dangerous withdrawal symptoms, and suffering psychological distress. (Long-term opioid use can cause physical dependency, an adaptive reaction that is different than the compulsive misuse associated with a substance use disorder.) It was too late for Gilmer. On July 7, 2021, the 38-year-old died by suicide.

Last August, an Ohio district court ruling set forth a new requirement for Walgreens, Walmart, and CVS pharmacists in two counties. These pharmacists must now document opioid prescriptions that are turned down, even for customers who have no previous purchases at that pharmacy, and they’re required to share this information with other locations in the same chain. None of the three pharmacies responded to an interview request from Leaps.org.

In a practice called red flagging, pharmacists may label a prescription suspicious for a variety of reasons, such as if a pharmacist observes an unusually high dose, a long distance from the patient’s home to the pharmacy, or cash payment. Pharmacists may question patients or prescribers to resolve red flags but, regardless of the explanation, they’re free to refuse to fill a prescription.

As the risk of litigation has grown, so has finger-pointing, says Seth Whitelaw, a compliance consultant at Whitelaw Compliance Group in West Chester, PA, who advises drug, medical device, and biotech companies. Drugmakers accused in National Prescription Opioid Litigation (NPOL), a complex set of thousands of cases on opioid epidemic deaths, which includes the Ohio district case, have argued that they shouldn’t be responsible for the large supply of opiates and overdose deaths. Yet, prosecutors alleged that these pharmaceutical companies hid addiction and overdose risks when labeling opioids, while distributors and pharmacists failed to identify suspicious orders or scripts.

Patients and pharmacists fear red flags

The requirements that pharmacists document prescriptions they refuse to fill so far only apply to two counties in Ohio. But Brushwood fears they will spread because of this precedent, and because there’s no way for pharmacists to predict what new legislation is on the way. “There is no definition of a red flag, there are no lists of red flags. There is no instruction on what to do when a red flag is detected. There’s no guidance on how to document red flags. It is a standardless responsibility,” Brushwood says. This adds trepidation for pharmacists—and more hoops to jump through for patients.

“I went into the doctor one day here and she said, ‘I'm going to stop prescribing opioids to all my patients effective immediately,” Nicolson says.

“We now have about a dozen studies that show that actually ripping somebody off their medication increases their risk of overdose and suicide by three to five times, destabilizes their health and mental health, often requires some hospitalization or emergency care, and can cause heart attacks,” says Kate Nicolson, founder of the National Pain Advocacy Center based in Boulder, Colorado. “It can kill people.” Nicolson was in pain for decades due to a surgical injury to the nerves leading to her spinal cord before surgeries fixed the problem.

Another issue is that primary care offices may view opioid use as a reason to turn down new patients. In a 2021 study, secret shoppers called primary care clinics in nine states, identifying themselves as long-term opioid users. When callers said their opioids were discontinued because their former physician retired, as opposed to an unspecified reason, they were more likely to be offered an appointment. Even so, more than 40 percent were refused an appointment. The study authors say their findings suggest that some physicians may try to avoid treating people who use opioids.

Abayomi-Paul says red flagging has changed how she fills prescriptions. “Once I go to one place, I try to [continue] going to that same place because of the amount of records that I have and making sure my medications don’t conflict,” Abayomi-Paul says.

Nicolson moved to Colorado from Washington D.C. in 2015, before the CDC issued its 2016 guidelines. When the guidelines came out, she found the change to be shockingly abrupt. “I went into the doctor one day here and she said, ‘I'm going to stop prescribing opioids to all my patients effective immediately.’” Since then, she’s spoken with dozens of patients who have been red-flagged or simply haven’t been able to access pain medication.

Despite her expertise, Nicolson isn’t positive she could successfully fill an opioid prescription today even if she needed one. At this point, she’s not sure exactly what various pharmacies would view as a red flag. And she’s not confident that these red flags even work. “You can have very legitimate reasons for being 50 miles away or having to go to multiple pharmacies, given that there are drug shortages now, as well as someone refusing to fill [a prescription.] It doesn't mean that you’re necessarily ‘drug seeking.’”

While there’s no easy solution. Whitelaw says clarifying the role of pharmacists and physicians in patient access to opioids could help people get the medication they need. He is seeking policy changes that focus on the needs of people in pain more than the number of prescriptions filled. He also advocates standardizing the definition of red flags and procedures for resolving them. Still, there will never be a single policy that can be applied to all people, explains Brushwood, the University of Florida professor. “You have to make a decision about each individual prescription.”

Can blockchain help solve the Henrietta Lacks problem?

Marielle Gross, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, shows patients a new app that tracks how their samples are used during biomedical research.

Science has come a long way since Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman from Baltimore, succumbed to cervical cancer at age 31 in 1951 -- only eight months after her diagnosis. Since then, research involving her cancer cells has advanced scientific understanding of the human papilloma virus, polio vaccines, medications for HIV/AIDS and in vitro fertilization.

Today, the World Health Organization reports that those cells are essential in mounting a COVID-19 response. But they were commercialized without the awareness or permission of Lacks or her family, who have filed a lawsuit against a biotech company for profiting from these “HeLa” cells.

While obtaining an individual's informed consent has become standard procedure before the use of tissues in medical research, many patients still don’t know what happens to their samples. Now, a new phone-based app is aiming to change that.

Tissue donors can track what scientists do with their samples while safeguarding privacy, through a pilot program initiated in October by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics and the University of Pittsburgh’s Institute for Precision Medicine. The program uses blockchain technology to offer patients this opportunity through the University of Pittsburgh's Breast Disease Research Repository, while assuring that their identities remain anonymous to investigators.

A blockchain is a digital, tamper-proof ledger of transactions duplicated and distributed across a computer system network. Whenever a transaction occurs with a patient’s sample, multiple stakeholders can track it while the owner’s identity remains encrypted. Special certificates called “nonfungible tokens,” or NFTs, represent patients’ unique samples on a trusted and widely used blockchain that reinforces transparency.

Blockchain could be used to notify people if cancer researchers discover that they have certain risk factors.

“Healthcare is very data rich, but control of that data often does not lie with the patient,” said Julius Bogdan, vice president of analytics for North America at the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), a Chicago-based global technology nonprofit. “NFTs allow for the encapsulation of a patient’s data in a digital asset controlled by the patient.” He added that this technology enables a more secure and informed method of participating in clinical and research trials.

Without this technology, de-identification of patients’ samples during biomedical research had the unintended consequence of preventing them from discovering what researchers find -- even if that data could benefit their health. A solution was urgently needed, said Marielle Gross, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive science and bioethics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

“A researcher can learn something from your bio samples or medical records that could be life-saving information for you, and they have no way to let you or your doctor know,” said Gross, who is also an affiliate assistant professor at the Berman Institute. “There’s no good reason for that to stay the way that it is.”

For instance, blockchain could be used to notify people if cancer researchers discover that they have certain risk factors. Gross estimated that less than half of breast cancer patients are tested for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 — tumor suppressor genes that are important in combating cancer. With normal function, these genes help prevent breast, ovarian and other cells from proliferating in an uncontrolled manner. If researchers find mutations, it’s relevant for a patient’s and family’s follow-up care — and that’s a prime example of how this newly designed app could play a life-saving role, she said.

Liz Burton was one of the first patients at the University of Pittsburgh to opt for the app -- called de-bi, which is short for decentralized biobank -- before undergoing a mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer in November, after it was diagnosed on a routine mammogram. She often takes part in medical research and looks forward to tracking her tissues.

“Anytime there’s a scientific experiment or study, I’m quick to participate -- to advance my own wellness as well as knowledge in general,” said Burton, 49, a life insurance service representative who lives in Carnegie, Pa. “It’s my way of contributing.”

Liz Burton was one of the first patients at the University of Pittsburgh to opt for the app before undergoing a mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer.

Liz Burton

The pilot program raises the issue of what investigators may owe study participants, especially since certain populations, such as Black and indigenous peoples, historically were not treated in an ethical manner for scientific purposes. “It’s a truly laudable effort,” Tamar Schiff, a postdoctoral fellow in medical ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, said of the endeavor. “Research participants are beautifully altruistic.”

Lauren Sankary, a bioethicist and associate director of the neuroethics program at Cleveland Clinic, agrees that the pilot program provides increased transparency for study participants regarding how scientists use their tissues while acknowledging individuals’ contributions to research.

However, she added, “it may require researchers to develop a process for ongoing communication to be responsive to additional input from research participants.”

Peter H. Schwartz, professor of medicine and director of Indiana University’s Center for Bioethics in Indianapolis, said the program is promising, but he wonders what will happen if a patient has concerns about a particular research project involving their tissues.

“I can imagine a situation where a patient objects to their sample being used for some disease they’ve never heard about, or which carries some kind of stigma like a mental illness,” Schwartz said, noting that researchers would have to evaluate how to react. “There’s no simple answer to those questions, but the technology has to be assessed with an eye to the problems it could raise.”

To truly make a difference, blockchain must enable broad consent from patients, not just de-identification.

As a result, researchers may need to factor in how much information to share with patients and how to explain it, Schiff said. There are also concerns that in tracking their samples, patients could tell others what they learned before researchers are ready to publicly release this information. However, Bogdan, the vice president of the HIMSS nonprofit, believes only a minimal study identifier would be stored in an NFT, not patient data, research results or any type of proprietary trial information.

Some patients may be confused by blockchain and reluctant to embrace it. “The complexity of NFTs may prevent the average citizen from capitalizing on their potential or vendors willing to participate in the blockchain network,” Bogdan said. “Blockchain technology is also quite costly in terms of computational power and energy consumption, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.”

In addition, this nascent, groundbreaking technology is immature and vulnerable to data security flaws, disputes over intellectual property rights and privacy issues, though it does offer baseline protections to maintain confidentiality. To truly make a difference, blockchain must enable broad consent from patients, not just de-identification, said Robyn Shapiro, a bioethicist and founding attorney at Health Sciences Law Group near Milwaukee.

The Henrietta Lacks story is a prime example, Shapiro noted. During her treatment for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins, Lacks’s tissue was de-identified (albeit not entirely, because her cell line, HeLa, bore her initials). After her death, those cells were replicated and distributed for important and lucrative research and product development purposes without her knowledge or consent.

Nonetheless, Shapiro thinks that the initiative by the University of Pittsburgh and Johns Hopkins has potential to solve some ethical challenges involved in research use of biospecimens. “Compared to the system that allowed Lacks’s cells to be used without her permission, Shapiro said, “blockchain technology using nonfungible tokens that allow patients to follow their samples may enhance transparency, accountability and respect for persons who contribute their tissue and clinical data for research.”

Read more about laws that have prevented people from the rights to their own cells.

New tech for prison reform spreads to 11 states

The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world, costing $182 billion per year, partly because its antiquated data systems often fail to identify people who should be released. A tech nonprofit is trying to change that.

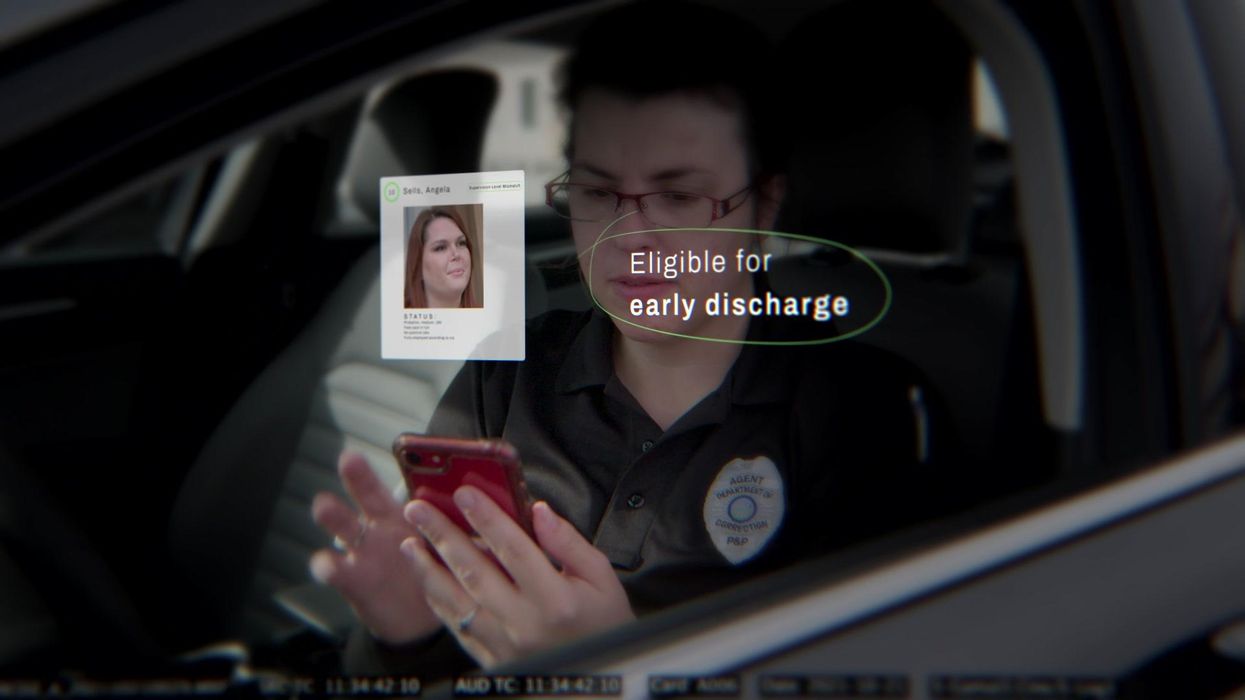

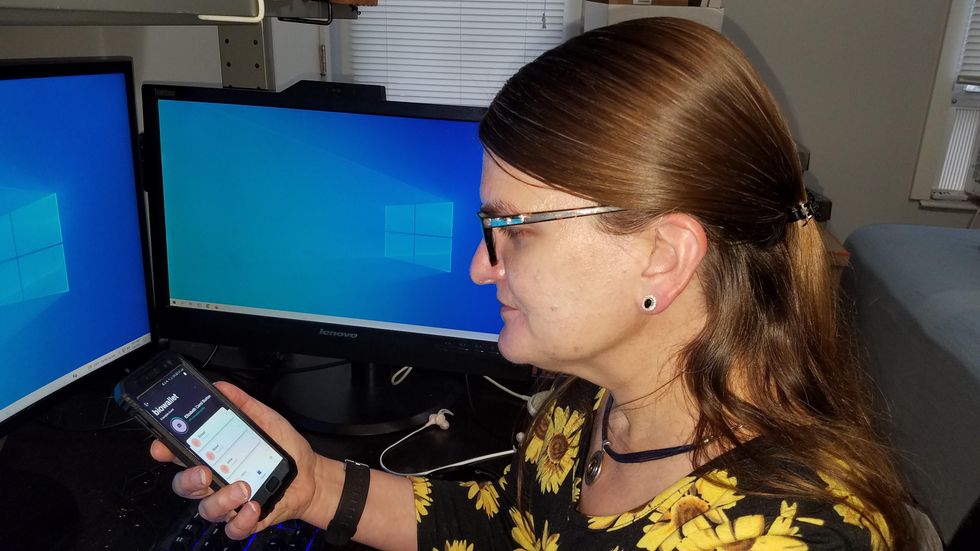

A new non-profit called Recidiviz is using data technology to reduce the size of the U.S. criminal justice system. The bi-coastal company (SF and NYC) is currently working with 11 states to improve their systems and, so far, has helped remove nearly 69,000 people — ones left floundering in jail or on parole when they should have been released.

“The root cause is fragmentation,” says Clementine Jacoby, 31, a software engineer who worked at Google before co-founding Recidiviz in 2019. In the 1970s and 80s, the U.S. built a series of disconnected data systems, and this patchwork is still being used by criminal justice authorities today. It requires parole officers to manually calculate release dates, leading to errors in many cases. “[They] have done everything they need to do to earn their release, but they're still stuck in the system,” Jacoby says.

Recidiviz has built a platform that connects the different databases, with the goal of identifying people who are already qualified for release but remain behind bars or on supervision. “Think of Recidiviz like Google Maps,” says Jacoby, who worked on Maps when she was at the tech giant. Google Maps takes in data from different sources – satellite images, street maps, local business data — and organizes it into one easy view. “Recidiviz does something similar with criminal justice data,” Jacoby explains, “making it easy to identify people eligible to come home or to move to less intensive levels of supervision.”

People like Jacoby’s uncle. His experience with incarceration is what inspired her passion for criminal justice reform in the first place.

The problems are vast

The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world — 2 million people according to the watchdog group, Prison Policy Initiative — at a cost of $182 billion a year. The numbers could be a lot lower if not for an array of problems including inaccurate sentencing calculations, flawed algorithms and parole violations laws.

Sentencing miscalculations

To determine eligibility for release, the current system requires corrections officers to check 21 different requirements spread across five different databases for each of the 90 to 100 people under their supervision. These manual calculations are time prohibitive, says Jacoby, and fall victim to human error.

In addition, Recidiviz found that policies aimed at helping to reduce the prison population don’t always work correctly. A key example is time off for good behavior laws that allow inmates to earn one day off for every 30 days of good behavior. Some states' data systems are built to calculate time off as one day per month of good behavior, rather than per day. Over the course of a decade-long sentence, Jacoby says these miscalculations can lead to a huge discrepancy in the calculated release data and the actual release date.

Algorithms

Commercial algorithm-based software systems for risk assessment continue to be widely used in the criminal justice system, even though a 2018 study published in Science Advances exposed their limitations. After the study went viral, it took three years for the Justice Department to issue a report on their own flawed algorithms used to reduce the federal prison population as part of the 2018 First Step Act. The program, it was determined, overestimated the risk of putting inmates of color into early-release programs.

Despite its name, Recidiviz does not build these types of algorithms for predicting recidivism, or whether someone will commit another crime after being released from prison. Rather, Jacoby says the company’s "descriptive analytics” approach is specifically intended to weed out incarceration inequalities and avoid algorithmic pitfalls.

Parole violation laws

Research shows that 350,000 people a year — about a quarter of the total prison population — are sent back not because they’ve committed another crime, but because they’ve broken a specific rule of their probation. “Things that wouldn't send you or I to prison, but would send someone on parole,” such as crossing county lines or being in the presence of alcohol when they shouldn’t be, are inflating the prison population, says Jacoby.

It’s personal for the co-founder and CEO

“I grew up with an uncle who went into the prison system,” Jacoby says. At 19, he was sentenced to ten years in prison for a non-violent crime. A few months after being released from jail, he was sent back for a non-violent parole violation.

“For my family, the fact that one in four prison admissions are driven not by a crime but by someone who's broken a rule on probation and parole was really profound because that happened to my uncle,” Jacoby says. The experience led her to begin studying criminal justice in high school, then college. She continued her dive into how the criminal justice system works as part of her Passion Project while at Google, a program that allows employees to spend 20 percent of their time on pro-bono work. Two colleagues whose family members had also been stuck in the system joined her.

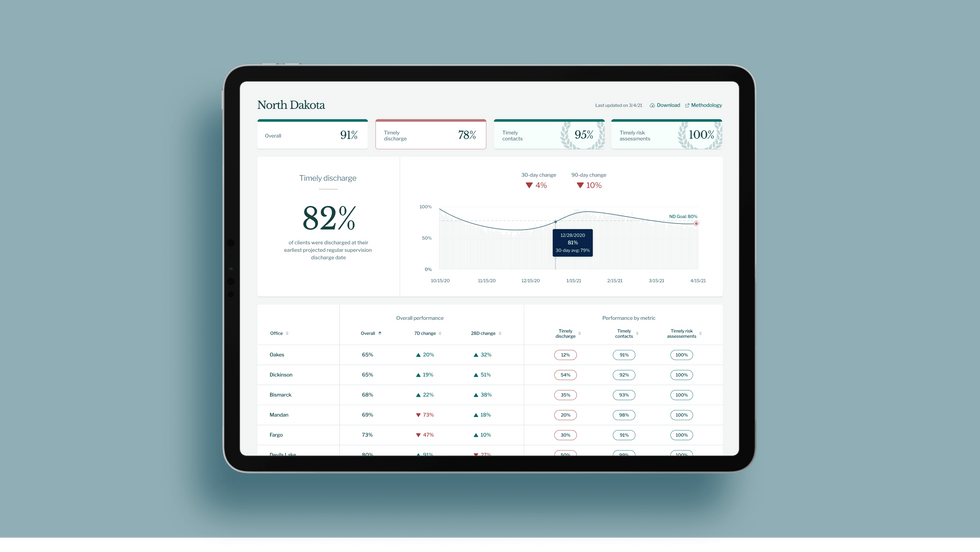

As part of the project, Jacoby interviewed hundreds of people involved in the criminal justice system. “Those on the right, those on the left, agreed that bad data was slowing down reform,” she says. Their research brought them to North Dakota where they began to understand the root of the problem. The corrections department is making “huge, consequential decisions every day [without] … the data,” Jacoby says. In a new video by Recidiviz not yet released, Jacoby recounts her exchange with the state’s director of corrections who told her, “‘It’s not that we have the data and we just don’t know how to make it public; we don’t have the information you think we have.'"

A mock-up (with fake data) of the types of dashboards and insights that Recidiviz provides to state governments.

Recidiviz

As a software engineer, Jacoby says the comment made no sense to her — until she witnessed it first-hand. “We spent a lot of time driving around in cars with corrections directors and parole officers watching them use these incredibly taxing, frankly terrible, old data systems,” Jacoby says.

As they weeded through thousands of files — some computerized, some on paper — they unearthed the consequences of bad data: Hundreds of people in prison well past their release date and thousands more whose release from parole was delayed because of minor paperwork issues. They found individuals stuck in parole because they hadn’t checked one last item off their eligibility list — like simply failing to provide their parole officer with a paystub. And, even when parolees advocated for themselves, the archaic system made it difficult for their parole officers to confirm their eligibility, so they remained in the system. Jacoby and her team also unpacked specific policies that drive racial disparities — such as fines and fees.

The Solution

It’s more than a trivial technical challenge to bring the incomplete, fragmented data onto a 21st century data platform. It takes months for Recidiviz to sift through a state’s information systems to connect databases “with the goal of tracking a person all the way through their journey and find out what’s working for 18- to 25-year-old men, what’s working for new mothers,” explains Jacoby in the video.

TED Talk: How bad data traps people in the U.S. justice system

TED Fellow Clementine Jacoby's TED Talk went live on Jan. 13. It describes how we can fix bad data in the criminal justice system, "bringing thousands of people home, reducing costs and improving public safety along the way."

Clementine Jacoby • TED2022

Ojmarrh Mitchell, an associate professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Arizona State University, who is not involved with the company, says what Recidiviz is doing is “remarkable.” His perspective goes beyond academic analysis. In his pre-academic years, Mitchell was a probation officer, working within the framework of the “well known, but invisible” information sharing issues that plague criminal justice departments. The flexibility of Recidiviz’s approach is what makes it especially innovative, he says. “They identify the specific gaps in each jurisdiction and tailor a solution for that jurisdiction.”

On the downside, the process used by Recidiviz is “a bit opaque,” Mitchell says, with few details available on how Recidiviz designs its tools and tracks outcomes. By sharing more information about how its actions lead to progress in a given jurisdiction, Recidiviz could help reformers in other places figure out which programs have the best potential to work well.

The eleven states in which Recidiviz is working include California, Colorado, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, Pennsylvania and Tennessee. And a pilot program launched last year in Idaho, if scaled nationally, with could reduce the number of people in the criminal justice system by a quarter of a million people, Jacoby says. As part of the pilot, rather than relying on manual calculations, Recidiviz is equipping leaders and the probation officers with actionable information with a few clicks of an app that Recidiviz built.

Mitchell is disappointed that there’s even the need for Recidiviz. “This is a problem that government agencies have a responsibility to address,” he says. “But they haven’t.” For one company to come along and fill such a large gap is “remarkable.”