Advances Bring First True Hope to Spinal Cord Injury Patients

Jeff Marquis and Kelly Thomas, fellow research participants and spinal cord injury patients, in a rehab session.

Seven years ago, mountain biking near his home in Whitefish, Montana, Jeff Marquis felt confident enough to try for a jump he usually avoided. But he hesitated just a bit as he was going over. Instead of catching air, Marquis crashed.

Researchers' major new insight is that recovery is still possible, even years after an injury.

After 18 days on a ventilator in intensive care and two-and-a-half months in a rehabilitation hospital, Marquis was able to move his arms and wrists, but not his fingers or anything below his chest. Still, he was determined to remain as independent as possible. "I wasn't real interested in having people take care of me," says Marquis, now 35. So, he dedicated the energy he formerly spent biking, kayaking, and snowboarding toward recovering his own mobility.

For generations, those like Marquis with severe spinal cord injuries dreamt of standing and walking again – with no realistic hope of achieving these dreams. But now, a handful of people with such injuries, including Marquis, have stood on their own and begun to learn to take steps again. "I'm always trying to improve the situation but I'm happy with where I'm at," Marquis says.

The recovery Marquis and a few of his fellow patients have achieved proves that our decades-old understanding of the spinal cord was wrong. Researchers' major new insight is that recovery is still possible, even years after an injury. Only a few thousand nerve cells actually die when the spinal cord is injured. The other neurons still have the ability to generate signals and movement on their own, says Susan Harkema, co-principal investigator at the Kentucky Spinal Cord Injury Research Center, where Marquis is being treated.

"The spinal cord has much more responsibility for executing movement than we thought before," Harkema says. "Successful movement can happen without those connections from the brain." Nerve cell circuits remaining after the injury can control movement, she says, but leaving people sitting in a wheelchair doesn't activate those sensory circuits. "When you sit down, you lose all the sensory information. The whole circuitry starts discombobulating."

Harkema and others use a two-pronged approach – both physical rehabilitation and electrical stimulation – to get those spinal cord circuits back into a functioning state. Several research groups are still honing this approach, but a few patients have already taken steps under their own power, and others, like Marquis, can now stand unassisted – both of which were merely fantasies for spinal cord injury patients just five years ago.

"This really does represent a leap forward in terms of how we think about the capacity of the spinal cord to be repaired after injury," says Susan Howley, executive vice president for research for the Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation, which supports research for spinal cord injuries.

Jeff Marquis biking on a rock before his accident.

This new biological understanding suggests the need for a wholesale change in how people are treated after a spinal cord injury, Howley says. But today, most insurance companies cover just 30-40 outpatient rehabilitation sessions per year, whether you've sprained your ankle or severed your spinal cord. To deliver the kind of therapy that really makes a difference for spinal cord injury patients requires "60-80-90 or 150 sessions," she says, adding that she thinks insurance companies will more than make up for the cost of those therapy sessions if spinal cord injury patients are healthier. Early evidence suggests that getting people back on their feet helps prevent medical problems common among paralyzed people, including urinary tract infections, which can require costly hospital stays.

"Exercise and the ability to fully bear one's own weight are as crucial for people who live with paralysis as they are for able-bodied people," Howley notes, adding that the Reeve Foundation is now trying to expand the network of facilities available in local communities to offer this essential rehabilitation.

"Providing the right kind of training every day to people could really improve their opportunity to recover," Harkema says.

It's not entirely clear yet how far someone could progress with rehabilitation alone, Harkema says, but probably the best results for someone with a severe injury will also require so-called epidural electrical stimulation. This device, implanted in the lower back for a cost of about $30,000, sends an electrical current at varying frequencies and intensities to the spinal cord. Several separate teams of researchers have now shown that epidural stimulation can help restore sensation and movement to people who have been paralyzed for years.

Epidural stimulation boosts the electrical signal that is generated below the point of injury, says Daniel Lu, an associate professor and vice chair of neurosurgery at the UCLA School of Medicine. Before a spinal cord injury, he says, a neuron might send a message at a volume of 10 but after injury, that volume might drop to a two or three. The epidural stimulation potentially trains the neuron to respond to the lower volume, Lu says.

Lu has used such stimulators to improve hand function – "essentially what defines us" – in two patients with spinal cord injuries. Both increased their grip strength so they now can lift a cup to drink by themselves, which they couldn't do before. He's also used non-invasive stimulation to help restore bladder function, which he says many spinal cord injury patients care about as much as walking again.

Not everyone will benefit from these treatments. People whose injury was caused by a cut to the spinal cord, as with a knife or bullet, probably can't be helped, Lu says, adding that they account for less than 5 percent of spinal cord injuries.

The current challenge Lu says is not how to stimulate the spinal cord, but where to stimulate it and the frequency of stimulation that will be most effective for each patient. Right now, doctors use an off-the-shelf stimulator that is used to treat pain and is not optimized for spinal cord patients, Harkema says.

Swiss researchers have shown impressive results from intermittent rather than continuous epidural stimulation. These pulses better reflect the way the brain sends its messages, according to Gregoire Courtine, the senior author on a pair of papers published Nov. 1 in Nature and Nature Neuroscience. He showed that he could get people up and moving within just a few days of turning on the stimulation. Three of his patients are walking again with only a walker or minimal assistance, and they also gained voluntary leg movements even when the stimulator was off. Continuous stimulation, this research shows, actually interferes with the patients' perception of limb position, and thus makes it harder for them to relearn to walk.

Even short of walking, proper physical rehabilitation and electrical stimulation can transform the quality of life of people with spinal cord injury, Howley and Harkema say. Patients don't need to be able to reach the top shelf or run a marathon to feel like they've been "cured" from their paralysis. Instead, recovering bowel, bladder and sexual functions, the ability to regulate their temperature and blood pressure, and reducing the breakdown of skin that can lead to a life-threatening infection can all be transformative – and all appear to improve with the combination of rehabilitation and electrical stimulation.

Howley cites a video of one of Harkema's patients, Stefanie Putnam, who was passing out five to six times a day because her blood pressure was so low. She couldn't be left alone, which meant she had no independence. After several months of rehabilitation and stimulation, she can now sit up for long periods, be left alone, and even, she says gleefully, cook her own dinner. "Every time I watch it, it brings me to tears," Howley says of the video. "She's able to resume her normal life activity. It's mind-boggling."

The work also suggests a transformation in the care of people immediately after injury. They should be allowed to stand and start taking steps as soon as possible, even if they cannot do it under their own power, Harkema says. Research is also likely to show that quickly implanting a stimulator after an injury will make a difference, she says.

There may be medications that can help immediately after an injury, too. One drug currently being studied, called riluzole, has already been approved for ALS and might help limit the damage of a spinal cord injury, Howley says. But testing its effectiveness has been a slow process, she says, because it needs to be given within 12 hours of the initial injury and not enough people get to the testing sites in time.

Stem cell therapy also offers promise for spinal cord injury patients, Howley says – but not the treatments currently provided by commercial stem cell clinics both in the U.S. and overseas, which she says are a sham. Instead, she is carefully following research by a California-based company called Asterias Biotherapeutics, which announced plans Nov. 8 to merge with a company called BioTime.

Asterias and a predecessor company have been treating people since 2010 in an effort to regrow nerves in the spinal cord. All those treated have safely tolerated the cells, but not everyone has seen a huge improvement, says Edward Wirth, who has led the trial work and is Asterias' chief medical director. He says he thinks he knows what's held back those who didn't improve much, and hopes to address those issues in the next 3- to 4-year-long trial, which he's now discussing with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

So far, he says, some patients have had an almost complete return of movement in their hands and arms, but little improvement in their legs. The stem cells seem to stimulate tissue repair and regeneration, he says, but only around the level of the injury in the spinal cord and a bit below. The legs, he says, are too far away to benefit.

Wirth says he thinks a combination of treatments – stem cells, electrical stimulation, rehabilitation, and improved care immediately after an injury – will likely produce the best results.

While there's still a long way to go to scale these advances to help the majority of the 300,000 spinal cord injury patients in the U.S., they now have something that's long been elusive: hope.

"Two or three decades ago there was no hope at all," Howley says. "We've come a long way."

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

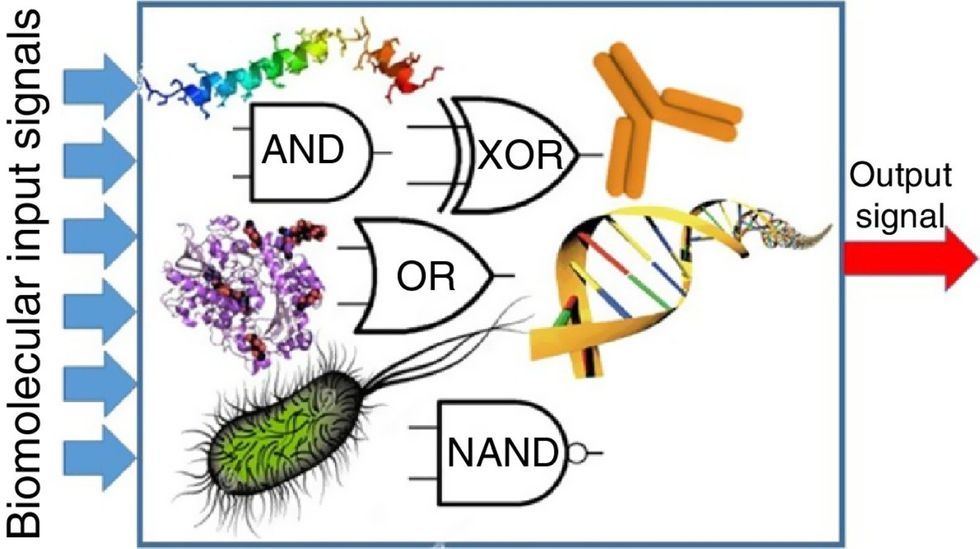

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.