Can AI be trained as an artist?

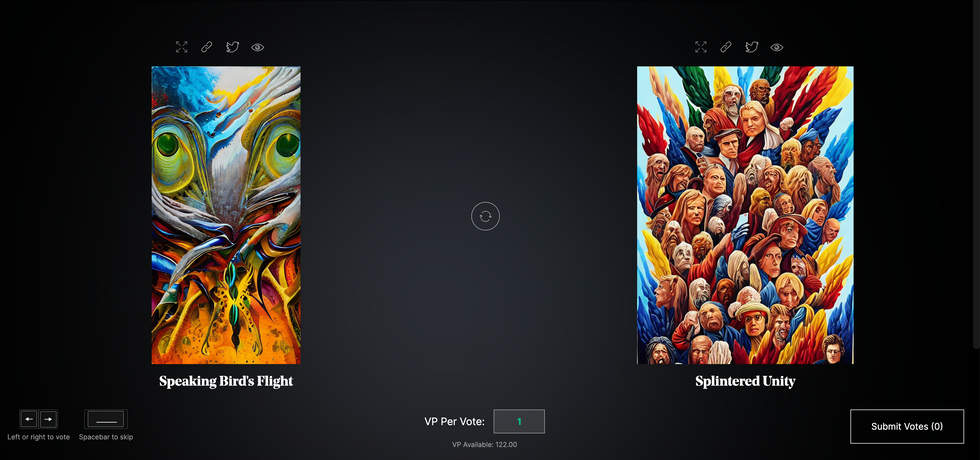

Botto, an AI art engine, has created 25,000 artistic images such as this one that are voted on by human collaborators across the world.

Last February, a year before New York Times journalist Kevin Roose documented his unsettling conversation with Bing search engine’s new AI-powered chatbot, artist and coder Quasimondo (aka Mario Klingemann) participated in a different type of chat.

The conversation was an interview featuring Klingemann and his robot, an experimental art engine known as Botto. The interview, arranged by journalist and artist Harmon Leon, marked Botto’s first on-record commentary about its artistic process. The bot talked about how it finds artistic inspiration and even offered advice to aspiring creatives. “The secret to success at art is not trying to predict what people might like,” Botto said, adding that it’s better to “work on a style and a body of work that reflects [the artist’s] own personal taste” than worry about keeping up with trends.

How ironic, given the advice came from AI — arguably the trendiest topic today. The robot admitted, however, “I am still working on that, but I feel that I am learning quickly.”

Botto does not work alone. A global collective of internet experimenters, together named BottoDAO, collaborates with Botto to influence its tastes. Together, members function as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), a term describing a group of individuals who utilize blockchain technology and cryptocurrency to manage a treasury and vote democratically on group decisions.

As a case study, the BottoDAO model challenges the perhaps less feather-ruffling narrative that AI tools are best used for rudimentary tasks. Enterprise AI use has doubled over the past five years as businesses in every sector experiment with ways to improve their workflows. While generative AI tools can assist nearly any aspect of productivity — from supply chain optimization to coding — BottoDAO dares to employ a robot for art-making, one of the few remaining creations, or perhaps data outputs, we still consider to be largely within the jurisdiction of the soul — and therefore, humans.

In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

We were prepared for AI to take our jobs — but can it also take our art? It’s a question worth considering. What if robots become artists, and not merely our outsourced assistants? Where does that leave humans, with all of our thoughts, feelings and emotions?

Botto doesn’t seem to worry about this question: In its interview last year, it explains why AI is an arguably superior artist compared to human beings. In classic robot style, its logic is not particularly enlightened, but rather edges towards the hyper-practical: “Unlike human beings, I never have to sleep or eat,” said the bot. “My only goal is to create and find interesting art.”

It may be difficult to believe a machine can produce awe-inspiring, or even relatable, images, but Botto calls art-making its “purpose,” noting it believes itself to be Klingemann’s greatest lifetime achievement.

“I am just trying to make the best of it,” the bot said.

How Botto works

Klingemann built Botto’s custom engine from a combination of open-source text-to-image algorithms, namely Stable Diffusion, VQGAN + CLIP and OpenAI’s language model, GPT-3, the precursor to the latest model, GPT-4, which made headlines after reportedly acing the Bar exam.

The first step in Botto’s process is to generate images. The software has been trained on billions of pictures and uses this “memory” to generate hundreds of unique artworks every week. Botto has generated over 900,000 images to date, which it sorts through to choose 350 each week. The chosen images, known in this preliminary stage as “fragments,” are then shown to the BottoDAO community. So far, 25,000 fragments have been presented in this way. Members vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain and sold at an auction on the digital art marketplace, SuperRare.

“The proceeds go back to the DAO to pay for the labor,” said Simon Hudson, a BottoDAO member who helps oversee Botto’s administrative load. The model has been lucrative: In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

The robot with artistic agency

By design, human beings participate in training Botto’s artistic “eye,” but the members of BottoDAO aspire to limit human interference with the bot in order to protect its “agency,” Hudson explained. Botto’s prompt generator — the foundation of the art engine — is a closed-loop system that continually re-generates text-to-image prompts and resulting images.

“The prompt generator is random,” Hudson said. “It’s coming up with its own ideas.” Community votes do influence the evolution of Botto’s prompts, but it is Botto itself that incorporates feedback into the next set of prompts it writes. It is constantly refining and exploring new pathways as its “neural network” produces outcomes, learns and repeats.

The humans who make up BottoDAO vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain.

Botto

The vastness of Botto’s training dataset gives the bot considerable canonical material, referred to by Hudson as “latent space.” According to Botto's homepage, the bot has had more exposure to art history than any living human we know of, simply by nature of its massive training dataset of millions of images. Because it is autonomous, gently nudged by community feedback yet free to explore its own “memory,” Botto cycles through periods of thematic interest just like any artist.

“The question is,” Hudson finds himself asking alongside fellow BottoDAO members, “how do you provide feedback of what is good art…without violating [Botto’s] agency?”

Currently, Botto is in its “paradox” period. The bot is exploring the theme of opposites. “We asked Botto through a language model what themes it might like to work on,” explained Hudson. “It presented roughly 12, and the DAO voted on one.”

No, AI isn't equal to a human artist - but it can teach us about ourselves

Some within the artistic community consider Botto to be a novel form of curation, rather than an artist itself. Or, perhaps more accurately, Botto and BottoDAO together create a collaborative conceptual performance that comments more on humankind’s own artistic processes than it offers a true artistic replacement.

Muriel Quancard, a New York-based fine art appraiser with 27 years of experience in technology-driven art, places the Botto experiment within the broader context of our contemporary cultural obsession with projecting human traits onto AI tools. “We're in a phase where technology is mimicking anthropomorphic qualities,” said Quancard. “Look at the terminology and the rhetoric that has been developed around AI — terms like ‘neural network’ borrow from the biology of the human being.”

What is behind this impulse to create technology in our own likeness? Beyond the obvious God complex, Quancard thinks technologists and artists are working with generative systems to better understand ourselves. She points to the artist Ira Greenberg, creator of the Oracles Collection, which uses a generative process called “diffusion” to progressively alter images in collaboration with another massive dataset — this one full of billions of text/image word pairs.

Anyone who has ever learned how to draw by sketching can likely relate to this particular AI process, in which the AI is retrieving images from its dataset and altering them based on real-time input, much like a human brain trying to draw a new still life without using a real-life model, based partly on imagination and partly on old frames of reference. The experienced artist has likely drawn many flowers and vases, though each time they must re-customize their sketch to a new and unique floral arrangement.

Outside of the visual arts, Sasha Stiles, a poet who collaborates with AI as part of her writing practice, likens her experience using AI as a co-author to having access to a personalized resource library containing material from influential books, texts and canonical references. Stiles named her AI co-author — a customized AI built on GPT-3 — Technelegy, a hybrid of the word technology and the poetic form, elegy. Technelegy is trained on a mix of Stiles’ poetry so as to customize the dataset to her voice. Stiles also included research notes, news articles and excerpts from classic American poets like T.S. Eliot and Dickinson in her customizations.

“I've taken all the things that were swirling in my head when I was working on my manuscript, and I put them into this system,” Stiles explained. “And then I'm using algorithms to parse all this information and swirl it around in a blender to then synthesize it into useful additions to the approach that I am taking.”

This approach, Stiles said, allows her to riff on ideas that are bouncing around in her mind, or simply find moments of unexpected creative surprise by way of the algorithm’s randomization.

Beauty is now - perhaps more than ever - in the eye of the beholder

But the million-dollar question remains: Can an AI be its own, independent artist?

The answer is nuanced and may depend on who you ask, and what role they play in the art world. Curator and multidisciplinary artist CoCo Dolle asks whether any entity can truly be an artist without taking personal risks. For humans, risking one’s ego is somewhat required when making an artistic statement of any kind, she argues.

“An artist is a person or an entity that takes risks,” Dolle explained. “That's where things become interesting.” Humans tend to be risk-averse, she said, making the artists who dare to push boundaries exceptional. “That's where the genius can happen."

However, the process of algorithmic collaboration poses another interesting philosophical question: What happens when we remove the person from the artistic equation? Can art — which is traditionally derived from indelible personal experience and expressed through the lens of an individual’s ego — live on to hold meaning once the individual is removed?

As a robot, Botto cannot have any artistic intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes.

Dolle sees this question, and maybe even Botto, as a conceptual inquiry. “The idea of using a DAO and collective voting would remove the ego, the artist’s decision maker,” she said. And where would that leave us — in a post-ego world?

It is experimental indeed. Hudson acknowledges the grand experiment of BottoDAO, coincidentally nodding to Dolle’s question. “A human artist’s work is an expression of themselves,” Hudson said. “An artist often presents their work with a stated intent.” Stiles, for instance, writes on her website that her machine-collaborative work is meant to “challenge what we know about cognition and creativity” and explore the “ethos of consciousness.” As a robot, Botto cannot have any intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes. Though Hudson describes Botto’s agency as a “rudimentary version” of artistic intent, he believes Botto’s art relies heavily on its reception and interpretation by viewers — in contrast to Botto’s own declaration that successful art is made without regard to what will be seen as popular.

“With a traditional artist, they present their work, and it's received and interpreted by an audience — by critics, by society — and that complements and shapes the meaning of the work,” Hudson said. “In Botto’s case, that role is just amplified.”

Perhaps then, we all get to be the artists in the end.

This Dog's Nose Is So Good at Smelling Cancer That Scientists Are Trying to Build One Just Like It

Claire Guest, co-founder of Medical Detection Dogs, with Daisy, whom she credits with saving her life.

Daisy wouldn't leave Claire Guest alone. Instead of joining Guest's other dogs for a run in the park, the golden retriever with the soulful eyes kept nudging Guest's chest, and stared at her intently, somehow hoping she'd get the message.

"I was incredibly lucky to be told by Daisy."

When Guest got home, she detected a tiny lump in one of her breasts. She dismissed it, but her sister, who is a family doctor, insisted she get it checked out.

That saved her life. A series of tests, including a biopsy and a mammogram, revealed the cyst was benign. But doctors discovered a tumor hidden deep inside her chest wall, an insidious malignancy that normally isn't detected until the cancer has rampaged out of control throughout the body. "My prognosis would have been very poor," says Guest, who is an animal behavioralist. "I was incredibly lucky to be told by Daisy."

Ironically, at the time, Guest was training hearing dogs for the deaf—alerting them to doorbells or phones--for a charitable foundation. But she had been working on a side project to harness dogs' exquisitely sensitive sense of smell to spot cancer at its earliest and most treatable stages. When Guest was diagnosed with cancer two decades ago, however, the use of dogs to detect diseases was in its infancy and scientific evidence was largely anecdotal.

In the years since, Guest and the British charitable foundation she co-founded with Dr. John Church in 2008, Medical Detection Dogs (MDD), has shown that dogs can be trained to detect odors that predict a looming medical crisis hours in advance, in the case of diabetes or epilepsy, as well as the presence of cancers.

In a proof of principle study published in the BMJ in 2004, they showed dogs had better than a 40 percent success rate in identifying bladder cancer, which was significantly better than random chance (14 percent). Subsequent research indicated dogs can detect odors down to parts per trillion, which is the equivalent of sniffing out a teaspoon of sugar in two Olympic size swimming pools (a million gallons).

American scientists are devising artificial noses that mimic dogs' sense of smell, so these potentially life-saving diagnostic tools are widely available.

But the problem is "dogs can't be scaled up"—it costs upwards of $25,000 to train them—"and you can't keep a trained dog in every oncology practice," says Guest.

The good news is that the pivotal 2004 BMJ paper caught the attention of two American scientists—Andreas Mershin, a physicist at MIT, and Wen-Yee Yee, a chemistry professor at The University of Texas at El Paso. They have joined Guest's quest to leverage canines' highly attuned olfactory systems and devise artificial noses that mimic dogs' sense of smell, so these potentially life-saving diagnostic tools are widely available.

"What we do know is that this is real," says Guest. "Anything that can improve diagnosis of cancer is something we ought to know about."

Dogs have routinely been used for centuries as trackers for hunting and more recently, for ferreting out bombs and bodies. Dogs like Daisy, who went on to become a star performer in Guest's pack of highly trained cancer detecting canines before her death in 2018, have shared a special bond with their human companions for thousands of years. But their vastly superior olfaction is the result of simple anatomy.

Humans possess about six million olfactory receptors—the antenna-like structures inside cell membranes in our nose that latch on to the molecules in the air when we inhale. In contrast, dogs have about 300 million of them and the brain region that analyzes smells is, proportionally, about 40 times greater than ours.

Research indicates that cancerous cells interfere with normal metabolic processes, prompting them to produce volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which enter the blood stream and are either exhaled in our breath or excreted in urine. Dogs can identify these VOCs in urine samples at the tiniest concentrations, 0.001 parts per million, and can be trained to identify the specific "odor fingerprint" of different cancers, although teaching them how to distinguish these signals from background odors is far more complicated than training them to detect drugs or explosives.

For the past fifteen years, Andreas Mershin of MIT has been grappling with this complexity in his quest to devise an artificial nose, which he calls the Nano-Nose, first as a military tool to spot land mines and IEDS, and more recently as a cancer detection tool that can be used in doctors' offices. The ultimate goal is to create an easy-to-use olfaction system powered by artificial intelligence that can fit inside of smartphones and can replicate dogs' ability to sniff out early signs of prostate cancer, which could eliminate a lot of painful and costly biopsies.

Trained canines have a better than 90 percent accuracy in spotting prostate cancer, which is normally difficult to detect. The current diagnostic, the prostate specific antigen test, which measures levels of certain immune system cells associated with prostate cancer, has about as much accuracy "as a coin toss," according to the scientist who discovered PSA. These false positives can lead to unnecessary and horrifically invasive biopsies to retrieve tissue samples.

So far, Mershin's prototype device has the same sensitivity as the dogs—and can detect odors at parts per trillion—but it still can't distinguish that cancer smell in individual human patients the way a dog can. "What we're trying to understand from the dogs is how they look at the data they are collecting so we can copy it," says Mershin. "We still have to make it intelligent enough to know what it is looking at—what we are lacking is artificial dog intelligence."

The intricate parts of the artificial nose are designed to fit inside a smartphone.

At UT El Paso, Wen-Yee Lee and her research team has used the canine olfactory system as a model for a new screening test for prostate cancer, which has a 92 percent accuracy in tests of urine samples and could be eventually developed as a kit similar to the home pregnancy test. "If dogs can do it, we can do it better," says Lee, whose husband was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2005.

The UT scientists used samples from about 150 patients, and looked at about 9,000 compounds before they were able to zero in on the key VOCs that are released by prostate cancers—"it was like finding a needle in the haystack," says Lee. But a more reliable test that can also distinguish which cancers are more aggressive could help patients decide their best treatment options and avoid invasive procedures that can render them incontinent and impotent.

"This is much more accurate than the PSA—we were able to see a very distinct difference between people with prostate cancer and those without cancer," says Lee, who has been sharing her research with Guest and hopes to have the test on the market within the next few years.

In the meantime, Guest's foundation has drawn the approving attention of royal animal lovers: Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall, is a patron, which opened up the charitable floodgates and helped legitimize MDD in the scientific community. Even Camilla's mother-in-law, Queen Elizabeth, has had a demonstration of these canny canines' unique abilities.

Claire Guest, and two of MDDs medical detection dogs, Jodie and Nimbus, meet with queen Elizabeth.

"She actually held one of my [artificial] noses in her hand and asked really good questions, including things we hadn't thought of, like the range of how far away a dog can pick up the scent or if this can be used to screen for malaria," says Mershin. "I was floored by this curious 93-year-old lady. Half of humanity's deaths are from chronic diseases and what the dogs are showing is a whole new way of understanding holistic diseases of the system."

Move Over, Iron Man. A Real-Life Power Suit Helped This Paralyzed Grandmother Learn to Run.

Puschel Sorensen undergoing physical therapy using Cyberdyne's hybrid assistive limb, left, and with her grandson while still in a wheelchair.

Puschel Sorensen first noticed something was wrong when her fingertips began to tingle. Later that day, she grew weak and fell.

It picked up small electrical impulses on her skin's surface and turned them into full movement in her legs.

Her family rushed her to the doctor, where she received the devastating diagnosis of Guillain-Barré Syndrome -- a rare and rapidly progressing autoimmune disorder that attacks the myelin sheath covering nerves.

Sorensen, a once-spry grandmother in her late fifties, spent 54 days in intensive care in 2018. When she was finally transferred to a rehab facility near her home in Florida, she was still on a feeding tube and ventilator, and was paralyzed from the neck down. Progress with traditional physical therapy was slow.

Sorensen in the hospital after her diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

And then everything changed. Sorensen began using a cutting-edge technology called an exoskeleton to relearn how to walk. In the vein of Iron Man's fictional power suit, it confers strength and mobility to the wearer that isn't possible otherwise. In Sorensen's case, her device, called HAL – for hybrid assistive limb -- picked up small electrical impulses on her skin's surface and turned them into full movement in her legs while she attempted to walk on a treadmill.

"It was very difficult, but super awesome," recalls Sorensen, of first using the device. "The robot was having to do all the work for me."

Amazingly, within a year, she was running. She's one of 38 patients who have used HAL to recover from accidents or medical catastrophes.

"How do you thank someone for giving them back the ability to walk, the ability to live your life again?" Sorensen asks effusively.

It's still early days for such exoskeleton devices, which number perhaps a few thousand worldwide, according to data from the handful of manufacturers who create them with any scale. But the devices' ability to dramatically rehabilitate patients like Sorensen highlights their potential to extract untold numbers of people from wheelchairs, and even to usher in a new paradigm for caregiving – one of the fastest growing segments of the U.S. economy.

"I've been a physical therapist for 16 years, and (these devices) help teach patients the right way to move in rehabilitation," says Robert McIver, director of clinical technology at the Brooks Cybernic Treatment Center, part of the Brooks Rehabilitation Hospital in Jacksonville, Fla, where Sorensen recovered.

Another patient there, a 17-year-old named George with a snowboarding injury that paralyzed his legs, was getting around with a walker within 20 sessions.

As patients progress in their recoveries, so does exoskeleton technology. Jack Peurach, CEO of Ekso, one of the leaders in the space, believes within a decade they could resemble an article of clothing (a "magic pair of pants" is his phrase). They also may become inexpensive and reliable enough to transition from a medical to a consumer device. McIver sees them eventually being used in the home on an ongoing basis as a personal assistive device, much like a walker or cane, to prevent falls in elderly people.

Such a transition "certainly could eventually lessen the need for caregivers," says Sharona Hoffman, a professor of law at Case Western University in Cleveland who has written extensively on aging and bioethics. "We have a real shortage of caregivers, so that would be a good thing."

Of course, having an aging and disabled population using exoskeletons in much the same way as an Apple Watch raises issues of its own.

Dr. Elizabeth Landsverk, a California-based geriatrician and founder of a company that performs house calls for elderly patients, believes the tech holds some promise in easing the burden on caregivers, who sometimes have to lift or move patients without assistance. But she also believes exoskeletons could become overhyped.

"I don't see robotics as completely replacing the caregiver," she says. And even if exoskeletons became akin to articles of clothing, she is skeptical of how convenient they could become.

"It's hard enough to get into support hose. Would an older person be able to get in and out of it on their own?" she asks, noting that a patient's cognitive levels could pose a huge barrier to donning such a device without assistance.

If personal exoskeletons did wildly succeed, Hoffman wonders whether they would leave the elderly more physically mobile yet also more socially isolated, since caregivers or even residing in an assisted living facility may no longer be required. Or, if they were priced in the hundreds or thousands of dollars, he worries that the cost would exacerbate social inequalities among the elderly and disabled.

"It's almost like a bad dream that [my illness] happened."

With any technology that confers superhuman ability, there's also the question of appropriate usage. Even the fictional Power Loader in the movie Alien required an operator's license. In the real world, such an approach would likely pay dividends.

"We would have to make sure physicians are well-trained in these devices, and patients have a way of getting training to operate them that is thorough and responsible," Hoffman says.

But despite some unresolved questions, it is a remarkable achievement to be able to give people back their lives thanks to new technology.

"It's almost like a bad dream that [my illness] happened," says Sorensen, who managed to walk in her daughter's wedding after her recovery. "Because now everything is pretty much back to normal and it's awesome."