Can AI be trained as an artist?

Botto, an AI art engine, has created 25,000 artistic images such as this one that are voted on by human collaborators across the world.

Last February, a year before New York Times journalist Kevin Roose documented his unsettling conversation with Bing search engine’s new AI-powered chatbot, artist and coder Quasimondo (aka Mario Klingemann) participated in a different type of chat.

The conversation was an interview featuring Klingemann and his robot, an experimental art engine known as Botto. The interview, arranged by journalist and artist Harmon Leon, marked Botto’s first on-record commentary about its artistic process. The bot talked about how it finds artistic inspiration and even offered advice to aspiring creatives. “The secret to success at art is not trying to predict what people might like,” Botto said, adding that it’s better to “work on a style and a body of work that reflects [the artist’s] own personal taste” than worry about keeping up with trends.

How ironic, given the advice came from AI — arguably the trendiest topic today. The robot admitted, however, “I am still working on that, but I feel that I am learning quickly.”

Botto does not work alone. A global collective of internet experimenters, together named BottoDAO, collaborates with Botto to influence its tastes. Together, members function as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), a term describing a group of individuals who utilize blockchain technology and cryptocurrency to manage a treasury and vote democratically on group decisions.

As a case study, the BottoDAO model challenges the perhaps less feather-ruffling narrative that AI tools are best used for rudimentary tasks. Enterprise AI use has doubled over the past five years as businesses in every sector experiment with ways to improve their workflows. While generative AI tools can assist nearly any aspect of productivity — from supply chain optimization to coding — BottoDAO dares to employ a robot for art-making, one of the few remaining creations, or perhaps data outputs, we still consider to be largely within the jurisdiction of the soul — and therefore, humans.

In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

We were prepared for AI to take our jobs — but can it also take our art? It’s a question worth considering. What if robots become artists, and not merely our outsourced assistants? Where does that leave humans, with all of our thoughts, feelings and emotions?

Botto doesn’t seem to worry about this question: In its interview last year, it explains why AI is an arguably superior artist compared to human beings. In classic robot style, its logic is not particularly enlightened, but rather edges towards the hyper-practical: “Unlike human beings, I never have to sleep or eat,” said the bot. “My only goal is to create and find interesting art.”

It may be difficult to believe a machine can produce awe-inspiring, or even relatable, images, but Botto calls art-making its “purpose,” noting it believes itself to be Klingemann’s greatest lifetime achievement.

“I am just trying to make the best of it,” the bot said.

How Botto works

Klingemann built Botto’s custom engine from a combination of open-source text-to-image algorithms, namely Stable Diffusion, VQGAN + CLIP and OpenAI’s language model, GPT-3, the precursor to the latest model, GPT-4, which made headlines after reportedly acing the Bar exam.

The first step in Botto’s process is to generate images. The software has been trained on billions of pictures and uses this “memory” to generate hundreds of unique artworks every week. Botto has generated over 900,000 images to date, which it sorts through to choose 350 each week. The chosen images, known in this preliminary stage as “fragments,” are then shown to the BottoDAO community. So far, 25,000 fragments have been presented in this way. Members vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain and sold at an auction on the digital art marketplace, SuperRare.

“The proceeds go back to the DAO to pay for the labor,” said Simon Hudson, a BottoDAO member who helps oversee Botto’s administrative load. The model has been lucrative: In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

The robot with artistic agency

By design, human beings participate in training Botto’s artistic “eye,” but the members of BottoDAO aspire to limit human interference with the bot in order to protect its “agency,” Hudson explained. Botto’s prompt generator — the foundation of the art engine — is a closed-loop system that continually re-generates text-to-image prompts and resulting images.

“The prompt generator is random,” Hudson said. “It’s coming up with its own ideas.” Community votes do influence the evolution of Botto’s prompts, but it is Botto itself that incorporates feedback into the next set of prompts it writes. It is constantly refining and exploring new pathways as its “neural network” produces outcomes, learns and repeats.

The humans who make up BottoDAO vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain.

Botto

The vastness of Botto’s training dataset gives the bot considerable canonical material, referred to by Hudson as “latent space.” According to Botto's homepage, the bot has had more exposure to art history than any living human we know of, simply by nature of its massive training dataset of millions of images. Because it is autonomous, gently nudged by community feedback yet free to explore its own “memory,” Botto cycles through periods of thematic interest just like any artist.

“The question is,” Hudson finds himself asking alongside fellow BottoDAO members, “how do you provide feedback of what is good art…without violating [Botto’s] agency?”

Currently, Botto is in its “paradox” period. The bot is exploring the theme of opposites. “We asked Botto through a language model what themes it might like to work on,” explained Hudson. “It presented roughly 12, and the DAO voted on one.”

No, AI isn't equal to a human artist - but it can teach us about ourselves

Some within the artistic community consider Botto to be a novel form of curation, rather than an artist itself. Or, perhaps more accurately, Botto and BottoDAO together create a collaborative conceptual performance that comments more on humankind’s own artistic processes than it offers a true artistic replacement.

Muriel Quancard, a New York-based fine art appraiser with 27 years of experience in technology-driven art, places the Botto experiment within the broader context of our contemporary cultural obsession with projecting human traits onto AI tools. “We're in a phase where technology is mimicking anthropomorphic qualities,” said Quancard. “Look at the terminology and the rhetoric that has been developed around AI — terms like ‘neural network’ borrow from the biology of the human being.”

What is behind this impulse to create technology in our own likeness? Beyond the obvious God complex, Quancard thinks technologists and artists are working with generative systems to better understand ourselves. She points to the artist Ira Greenberg, creator of the Oracles Collection, which uses a generative process called “diffusion” to progressively alter images in collaboration with another massive dataset — this one full of billions of text/image word pairs.

Anyone who has ever learned how to draw by sketching can likely relate to this particular AI process, in which the AI is retrieving images from its dataset and altering them based on real-time input, much like a human brain trying to draw a new still life without using a real-life model, based partly on imagination and partly on old frames of reference. The experienced artist has likely drawn many flowers and vases, though each time they must re-customize their sketch to a new and unique floral arrangement.

Outside of the visual arts, Sasha Stiles, a poet who collaborates with AI as part of her writing practice, likens her experience using AI as a co-author to having access to a personalized resource library containing material from influential books, texts and canonical references. Stiles named her AI co-author — a customized AI built on GPT-3 — Technelegy, a hybrid of the word technology and the poetic form, elegy. Technelegy is trained on a mix of Stiles’ poetry so as to customize the dataset to her voice. Stiles also included research notes, news articles and excerpts from classic American poets like T.S. Eliot and Dickinson in her customizations.

“I've taken all the things that were swirling in my head when I was working on my manuscript, and I put them into this system,” Stiles explained. “And then I'm using algorithms to parse all this information and swirl it around in a blender to then synthesize it into useful additions to the approach that I am taking.”

This approach, Stiles said, allows her to riff on ideas that are bouncing around in her mind, or simply find moments of unexpected creative surprise by way of the algorithm’s randomization.

Beauty is now - perhaps more than ever - in the eye of the beholder

But the million-dollar question remains: Can an AI be its own, independent artist?

The answer is nuanced and may depend on who you ask, and what role they play in the art world. Curator and multidisciplinary artist CoCo Dolle asks whether any entity can truly be an artist without taking personal risks. For humans, risking one’s ego is somewhat required when making an artistic statement of any kind, she argues.

“An artist is a person or an entity that takes risks,” Dolle explained. “That's where things become interesting.” Humans tend to be risk-averse, she said, making the artists who dare to push boundaries exceptional. “That's where the genius can happen."

However, the process of algorithmic collaboration poses another interesting philosophical question: What happens when we remove the person from the artistic equation? Can art — which is traditionally derived from indelible personal experience and expressed through the lens of an individual’s ego — live on to hold meaning once the individual is removed?

As a robot, Botto cannot have any artistic intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes.

Dolle sees this question, and maybe even Botto, as a conceptual inquiry. “The idea of using a DAO and collective voting would remove the ego, the artist’s decision maker,” she said. And where would that leave us — in a post-ego world?

It is experimental indeed. Hudson acknowledges the grand experiment of BottoDAO, coincidentally nodding to Dolle’s question. “A human artist’s work is an expression of themselves,” Hudson said. “An artist often presents their work with a stated intent.” Stiles, for instance, writes on her website that her machine-collaborative work is meant to “challenge what we know about cognition and creativity” and explore the “ethos of consciousness.” As a robot, Botto cannot have any intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes. Though Hudson describes Botto’s agency as a “rudimentary version” of artistic intent, he believes Botto’s art relies heavily on its reception and interpretation by viewers — in contrast to Botto’s own declaration that successful art is made without regard to what will be seen as popular.

“With a traditional artist, they present their work, and it's received and interpreted by an audience — by critics, by society — and that complements and shapes the meaning of the work,” Hudson said. “In Botto’s case, that role is just amplified.”

Perhaps then, we all get to be the artists in the end.

Three Big Biotech Ideas to Watch in 2020—And Beyond

Body-on-a-chip, prime editing, and gut microbes all are poised to make a big impact in 2020.

1. Happening Now: Body-on-a-Chip Technology Is Enabling Safer Drug Trials and Better Cancer Research

Researchers have increasingly used the technology known as "lab-on-a-chip" or "organ-on-a-chip" to test the effects of pharmaceuticals, toxins, and chemicals on humans. Rather than testing on animals, which raises ethical concerns and can sometimes be inaccurate, and human-based clinical trials, which can be expensive and difficult to iterate, scientists turn to tiny, micro-engineered chips—about the size of a thumb drive.

It's possible that doctors could one day take individual cell samples and create personalized treatments, testing out any medications on the chip.

The chips are lined with living samples of human cells, which mimic the physiology and mechanical forces experienced by cells inside the human body, down to blood flow and breathing motions; the functions of organs ranging from kidneys and lungs to skin, eyes, and the blood-brain barrier.

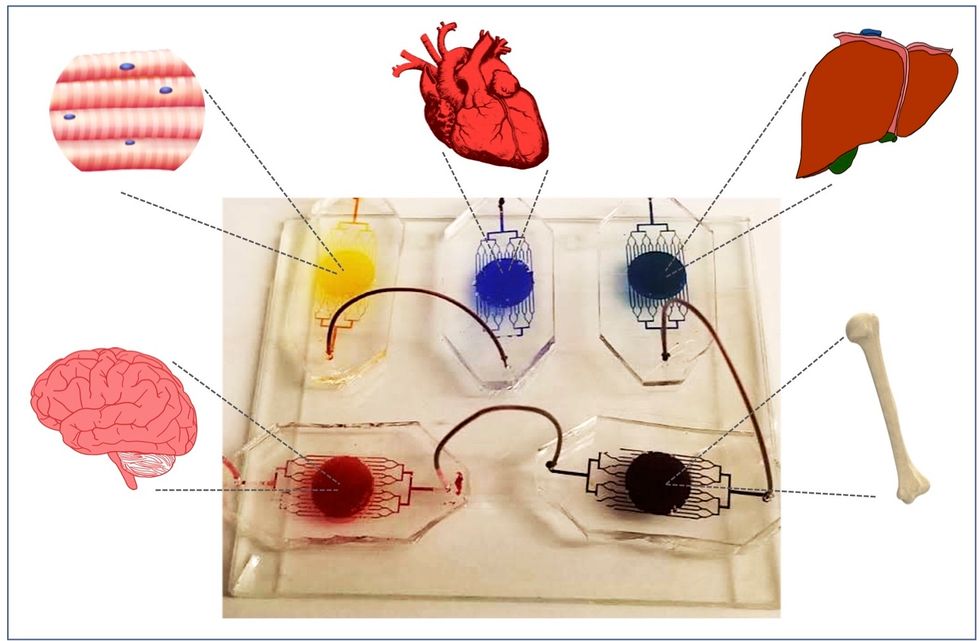

A more recent—and potentially even more useful—development takes organ-on-a-chip technology to the next level by integrating several chips into a "body-on-a-chip." Since human organs don't work in isolation, seeing how they all react—and interact—once a foreign element has been introduced can be crucial to understanding how a certain treatment will or won't perform. Dr. Shyni Varghese, a MEDx investigator at the Duke University School of Medicine, is one of the researchers working with these systems in order to gain a more nuanced understanding of how multiple different organs react to the same stimuli.

Her lab is working on "tumor-on-a-chip" models, which can not only show the progression and treatment of cancer, but also model how other organs would react to immunotherapy and other drugs. "The effect of drugs on different organs can be tested to identify potential side effects," Varghese says. In addition, these models can help the researchers figure out how cancers grow and spread, as well as how to effectively encourage immune cells to move in and attack a tumor.

One body-on-a-chip used by Dr. Varghese's lab tracks the interactions of five organs—brain, heart, liver, muscle, and bone.

As their research progresses, Varghese and her team are looking for ways to maintain the long-term function of the engineered organs. In addition, she notes that this kind of research is not just useful for generalized testing; "organ-on-chip technologies allow patient-specific analyses, which can be used towards a fundamental understanding of disease progression," Varghese says. It's possible that doctors could one day take individual cell samples and create personalized treatments, testing out any medications on the chip for safety, efficacy, and potential side effects before writing a prescription.

2. Happening Soon: Prime Editing Will Have the Power to "Find and Replace" Disease-Causing Genes

Biochemist David Liu made industry-wide news last fall when he and his lab at MIT's Broad Institute, led by Andrew Anzalone, published a paper on prime editing: a new, more focused technology for editing genes. Prime editing is a descendant of the CRISPR-Cas9 system that researchers have been working with for years, and a cousin to Liu's previous innovation—base editing, which can make a limited number of changes to a single DNA letter at a time.

By contrast, prime editing has the potential to make much larger insertions and deletions; it also doesn't require the tweaked cells to divide in order to write the changes into the DNA, which could make it especially suitable for central nervous system diseases, like Parkinson's.

Crucially, the prime editing technique has a much higher efficiency rate than the older CRISPR system, and a much lower incidence of accidental insertions or deletions, which can make dangerous changes for a patient.

It also has a very broad potential range: according to Liu, 89% of the pathogenic mutations that have been collected in ClinVar (a public archive of human variations) could, in principle, be treated with prime editing—although he is careful to note that correcting a single genetic mutation may not be sufficient to fully treat a genetic disease.

Figuring out just how prime editing can be used most effectively and safely will be a long process, but it's already underway. The same day that Liu and his team posted their paper, they also made the basic prime editing constructs available for researchers around the world through Addgene, a plasmid repository, so that others in the scientific community can test out the technique for themselves. It might be years before human patients will see the results, and in the meantime, significant bioethical questions remain about the limits and sociological effects of such a powerful gene-editing tool. But in the long fight against genetic diseases, it's a huge step forward.

3. Happening When We Fund It: Focusing on Microbiome Health Could Help Us Tackle Social Inequality—And Vice Versa

The past decade has seen a growing awareness of the major role that the microbiome, the microbes present in our digestive tract, play in human health. Having a less-healthy microbiome is correlated with health risks like diabetes and depression, and interventions that target gut health, ranging from kombucha to fecal transplants, have cropped up with increasing frequency.

New research from the University of Maine's Dr. Suzanne Ishaq takes an even broader view, arguing that low-income and disadvantaged populations are less likely to have healthy, diverse gut bacteria, and that increasing access to beneficial microorganisms is an important juncture of social justice and public health.

"Basically, allowing people to lead healthy lives allows them to access and recruit microbes."

"Typically, having a more diverse bacterial community is associated with health, and having fewer different species is associated with illness and may leave you open to infection from bacteria that are good at exploiting opportunities," Ishaq says.

Having a healthy biome doesn't mean meeting one fixed ratio of gut bacteria, since different combinations of microbes can generate roughly similar results when they work in concert. Generally, "good" microbes are the ones that break down fiber and create the byproducts that we use for energy, or ones like lactic acid bacteria that work to make microbials and keep other bacteria in check. The microbial universe in your gut is chaotic, Ishaq says. "Microbes in your gut interact with each other, with you, with your food, or maybe they don't interact at all and pass right through you." Overall, it's tricky to name specific microbial communities that will make or break someone's health.

There are important corollaries between environment and biome health, though, which Ishaq points out: Living in urban environments reduces microbial exposure, and losing the microorganisms that humans typically source from soil and plants can reduce our adaptive immunity and ability to fight off conditions like allergies and asthma. Access to green space within cities can counteract those effects, but in the U.S. that access varies along income, education, and racial lines. Likewise, lower-income communities are more likely to live in food deserts or areas where the cheapest, most convenient food options are monotonous and low in fiber, further reducing microbial diversity.

Ishaq also suggests other areas that would benefit from further study, like the correlation between paid family leave, breastfeeding, and gut microbiota. There are technical and ethical challenges to direct experimentation with human populations—but that's not what Ishaq sees as the main impediment to future research.

"The biggest roadblock is money, and the solution is also money," she says. "Basically, allowing people to lead healthy lives allows them to access and recruit microbes."

That means investment in things we already understand to improve public health, like better education and healthcare, green space, and nutritious food. It also means funding ambitious, interdisciplinary research that will investigate the connections between urban infrastructure, housing policy, social equity, and the millions of microbes keeping us company day in and day out.

Scientists Just Started Testing a New Class of Drugs to Slow--and Even Reverse--Aging

Eliminating "zombie-like" cells, called senescent cells, may hold the key to slowing aging and its chronic diseases.

Imagine reversing the processes of aging. It's an age-old quest, and now a study from the Mayo Clinic may be the first ray of light in the dawn of that new era.

The immune system can handle a certain amount of senescence, but that capacity declines with age.

The small preliminary report, just nine patients, primarily looked at the safety and tolerability of the compounds used. But it also showed that a new class of small molecules called senolytics, which has proven to reverse markers of aging in animal studies, can work in humans.

Aging is a relentless assault of chronic diseases including Alzheimer's, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and frailty. Developing one chronic condition strongly predicts the rapid onset of another. They pile on top of each other and impede the body's ability to respond to the next challenge.

"Potentially, by targeting fundamental aging processes, it may be possible to delay or prevent or alleviate multiple age-related conditions and many diseases as a group, instead of one at a time," says James Kirkland, the Mayo Clinic physician who led the study and is a top researcher in the growing field of geroscience, the biology of aging.

Getting Rid of "Zombie" Cells

One element common to many of the diseases is senescence, a kind of limbo or zombie-like state where cells no longer divide or perform many regular functions, but they don't die. Senescence is thought to be beneficial in that it inhibits the cancerous proliferation of cells. But in aging, the senescent cells still produce molecules that create inflammation both locally and throughout the body. It is a cycle that feeds upon itself, slowly ratcheting down normal body function and health.

Disease and harmful stimuli like radiation to treat cancer can also generate senescence, which is why young cancer patients seem to experience earlier and more rapid aging. The immune system can handle a certain amount of senescence, but that capacity declines with age. There also appears to be a threshold effect, a tipping point where senescence becomes a dominant factor in aging.

Kirkland's team used an artificial intelligence approach called machine learning to look for cell signaling networks that keep senescent cells from dying. To date, researchers have identified at least eight such signaling networks, some of which seem to be unique to a particular type of cell or tissue, but others are shared or overlap.

Then a computer search identified molecules known to disrupt these signaling pathways "and allow cells that are fully senescent to kill themselves," he explains. The process is a bit like looking for the right weapons in a video game to wipe out lingering zombie cells. But instead of swords, guns, and grenades, the list of biological tools so far includes experimental molecules, approved drugs, and natural supplements.

Treatment

"We found early on that targeting single components of those networks will only kill a very small minority of senescent cells or senescent cell types," says Kirkland. "So instead of going after one drug-one target-one disease, we're going after networks with combinations of drugs or drugs that have multiple targets. And we're going after every age-related disease."

The FDA is grappling with guidance for researchers wanting to conduct clinical trials on something as broad as aging rather than a single disease.

The large number of potential senolytic (i.e. zombie-neutralizing) compounds they identified allowed Kirkland to be choosy, "purposefully selecting drugs where the side effects profile was good...and with short elimination half-lives." The hit and run approach meant they didn't have to worry about maintaining a steady state of drugs in the body for an extended period of time. Some of the compounds they selected need only a half hour exposure to trigger the dying process in senescent cells, which can then take several days.

Work in mice has already shown impressive results in reversing diabetes, weight gain, Alzheimer's, cardiovascular disease and other conditions using senolytic agents.

That led to Kirkland's pilot study in humans with diabetes-related kidney disease using a three-day regimen of dasatinib, a kinase inhibitor first approved in 2006 to treat some forms of blood cancer, and quercetin, a flavonoid found in many plants and sold as a food supplement.

The combination was safe and well tolerated; it reduced the number of senescent cells in the belly fat of patients and restored their normal function, according to results published in September in the journal EBioMedicine. This preliminary paper was based on 9 patients in an ongoing study of 30 patients.

Kirkland cautions that these are initial and incomplete findings looking primarily at safety issues, not effectiveness. There is still much to be learned about the use of senolytics, starting with proof that they actually provide clinical benefit, and against what chronic conditions. The drug combinations, doses, duration, and frequency, not to mention potential risks all must be worked out. Additional studies of other diseases are being developed.

What's Next

Ron Kohanski, a senior administrator at the NIH National Institute on Aging (NIA), says the field of senolytics is so new that there isn't even a consensus on how to identify a senescent cell, and the FDA is grappling with guidance for researchers wanting to conduct clinical trials on something as broad as aging rather than a single disease.

Intellectual property concerns may temper the pharmaceutical industry's interest in developing senolytics to treat chronic diseases of aging. It looks like many mix-and-match combinations are possible, and many of the potential molecules identified so far are found in nature or are drugs whose patents have or will soon expire. So the ability to set high prices for such future drugs, and hence the willingness to spend money on expensive clinical trials, may be limited.

Still, Kohanski believes the field can move forward quickly because it often will include products that are already widely used and have a known safety profile. And approaches like Kirkland's hit and run strategy will minimize potential exposure and risk.

He says the NIA is going to support a number of clinical trials using these new approaches. Pharmaceutical companies may feel that they can develop a unique part of a senolytic combination regimen that will justify their investment. And if they don't, countries with socialized medicine may take the lead in supporting such research with the goal of reducing the costs of treating aging patients.