Anti-Aging Pioneer Aubrey de Grey: “People in Middle Age Now Have a Fair Chance”

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Aubrey de Grey at the World Stem Cell Summit in Miami on January 25, 2018.

Aging is not a mystery, says famed researcher Dr. Aubrey de Grey, perhaps the world's foremost advocate of the provocative view that medical technology will one day allow humans to control the aging process and live healthily into our hundreds—or even thousands.

"The cultural attitudes toward all of this are going to be completely turned upside down by sufficiently promising results in the lab, in mice."

He likens aging to a car wearing down over time; as the body operates normally, it accumulates damage which can be tolerated for a while, but eventually sends us into steep decline. The most promising way to escape this biological reality, he says, is to repair the damage as needed with precise scientific tools.

The bad news is that doing this groundbreaking research takes a long time and a lot of money, which has not always been readily available, in part due to a cultural phenomenon he terms "the pro-aging trance." Cultural attitudes have long been fatalistic about the inevitability of aging; many people balk at the seemingly implausible prospect of indefinite longevity.

But the good news for de Grey—and those who are cheering him on—is that his view is becoming less radical these days. Both the academic and private sectors are racing to tackle aging; his own SENS Research Foundation, for one, has spun out into five different companies. Defeating aging, he says, "is not just a future industry; it's an industry now that will be both profitable and extremely good for your health."

De Grey sat down with Editor-in-Chief Kira Peikoff at the World Stem Cell Summit in Miami to give LeapsMag the latest scoop on his work. Here is an edited and condensed version of our conversation.

Since your book Ending Aging was published a decade ago, scientific breakthroughs in stem cell research, genome editing, and other fields have taken the world by storm. Which of these have most affected your research?

They have all affected it a lot in one way, and hardly at all in another way. They have speeded it up--facilitated short cuts, ways to get where we're already trying to go. What they have not done is identified any fundamental changes to the overall strategy. In the book, we described the seven major types of damage, and particular ways of going about fixing each of them, and that hasn't changed.

"Repair at the microscopic level, one would be able to expect to do without surgery, just by injecting the right kind of stem cells."

Has any breakthrough specifically made the biggest impact?

It's not just the obvious things, like iPS (induced pluripotent stem cells) and CRISPR (a precise tool for editing genes). It's also the more esoteric things that applied specifically to certain of our areas, but most people don't really know about them. For example, the identification of how to control something called co-translational mitochondrial protein import.

How much of the future of anti-aging treatments will involve regeneration of old tissue, or wholesale growth of new organs?

The more large-scale ones, regenerating whole new organs, are probably only going to play a role in the short-term and will be phased out relatively rapidly, simply because, in order to be useful, one has to employ surgery, which is really invasive. We'll want to try to get around that, but it seems quite likely that in the very early stages, the techniques we have for repairing things at the molecular and cellular level in situ will be insufficiently comprehensive, and so we will need to do the more sledgehammer approach of building a whole new organ and sticking it in.

Every time you are in a position where you're replacing an organ, you have the option, in principle, of repairing the organ, without replacing it. And repair at the microscopic level, one would be able to expect to do without surgery, just by injecting the right kind of stem cells or whatever. That would be something one would expect to be able to apply to someone much closer to death's door and much more safely in general, and probably much more cheaply. One would expect that subsequent generations of these therapies would move in that direction.

Your foundation is working on an initiative requiring $50 million in funding—

Well, if we had $50 million per year in funding, we could go about three times faster than we are on $5 million per year.

And you're looking at a 2021 timeframe to start human trials?

That's approximate. Remember, because we accumulate in the body so many different types of damage, that means we have many different types of therapy to repair that damage. And of course, each of those types has to be developed independently. It's very much a divide and conquer therapy. The therapies interact with each other to some extent; the repair of one type of damage may slow down the creation of another type of damage, but still that's how it's going to be.

And some of these therapies are much easier to implement than others. The easier components of what we need to do are already in clinical trials—stem cell therapies especially, and immunotherapy against amyloid in the brain, for example. Even in phase III clinical trials in some cases. So when I talk about a timeframe like 2021, or early 20s shall we say, I'm really talking about the most difficult components.

What recent strides are you most excited about?

Looking back over the past couple of years, I'm particularly proud of the successes we've had in the very most difficult areas. If you go through the 7 components of SENS, there are two that have absolutely been stuck in a rut and have gotten nowhere for 15 to 20 years, and we basically fixed that in both cases. We published two years ago in Science magazine that essentially showed a way forward against the stiffening of the extracellular matrix, which is responsible for things like wrinkles and hypertension. And then a year ago, we published a real breakthrough paper with regard to placing copies of the mitochondria DNA in the nuclear DNA modified in such a way that they still work, which is an idea that had been around for 30 years; everyone had given up on it, some a long time ago, and we basically revived it.

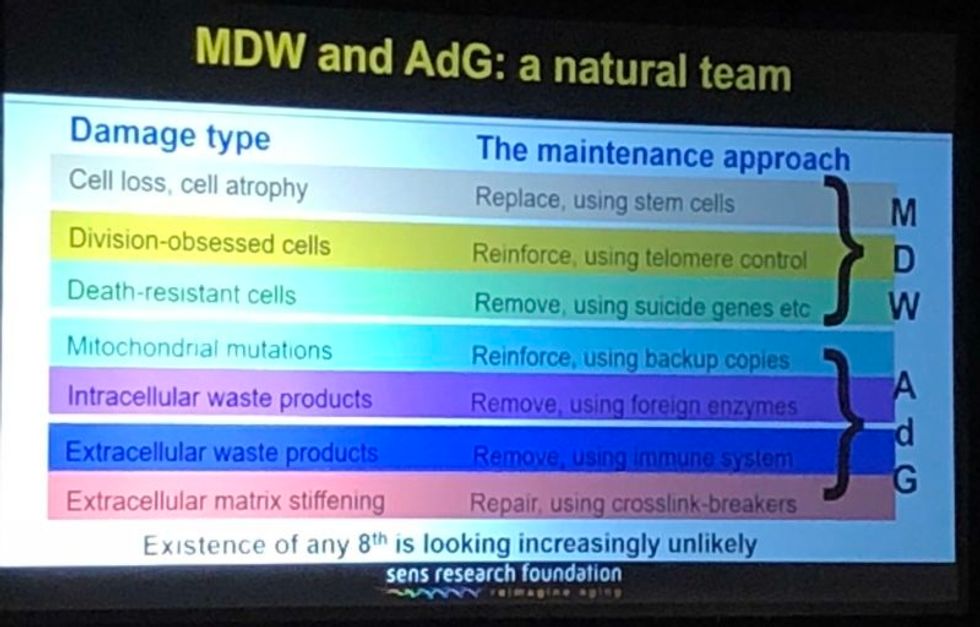

A slide presented by Aubrey de Grey, referencing his collaboration with Mike West at AgeX, showing the 7 types of damage that he believes must be repaired to end aging.

(Courtesy Kira Peikoff)

That's exciting. What do you think are the biggest barriers to defeating aging today: the technological challenges, the regulatory framework, the cost, or the cultural attitude of the "pro-aging" trance?

One can't really address those independently of each other. The technological side is one thing; it's hard, but we know where we're going, we've got a plan. The other ones are very intertwined with each other. A lot of people are inclined to say, the regulatory hurdle will be completely insurmountable, plus people don't recognize aging as a disease, so it's going to be a complete nonstarter. I think that's nonsense. And the reason is because the cultural attitudes toward all of this are going to be completely turned upside down before we have to worry about the regulatory hurdles. In other words, they're going to be turned upside down by sufficiently promising results in the lab, in mice. Once we get to be able to rejuvenate actually old mice really well so they live substantially longer than they otherwise would have done, in a healthy state, everyone's going to know about it and everyone's going to demand – it's not going to be possible to get re-elected unless you have a manifesto commitment to turn the FDA completely upside down and make sure this happens without any kind of regulatory obstacle.

I've been struggling away all these years trying to bring little bits of money in the door, and the reason I have is because of the skepticism as to regards whether this could actually work, combined with the pro-aging trance, which is a product of the skepticism – people not wanting to get their hopes up, so finding excuses about aging being a blessing in disguise, so they don't have to think about it. All of that will literally disintegrate pretty much overnight when we have the right kind of sufficiently impressive progress in the lab. Therefore, the availability of money will also [open up]. It's already cracking: we're already seeing the beginnings of the actual rejuvenation biotechnology industry that I've been talking about with a twinkle in my eye for some years.

"For humans, a 50-50 chance would be twenty years at this point, and there's a 10 percent chance that we won't get there for a hundred years."

Why do you think the culture is starting to shift?

There's no one thing yet. There will be that tipping point I mentioned, perhaps five years from now when we get a real breakthrough, decisive results in mice that make it simply impossible to carry on being fatalistic about all this. Prior to that, what we're already seeing is the impact of sheer old-school repeat advertising—me going out there, banging away and saying the same fucking thing again and again, and nobody saying anything that persuasively knocks me down. … And it's also the fact that we are making incremental amounts of progress, not just ourselves, but the scientific community generally. It has become incrementally more plausible that what I say might be true.

I'm sure you hate getting the timeline question, but if we're five years away from this breakthrough in mice, it's hard to resist asking—how far is that in terms of a human cure?

When I give any kind of timeframes, the only real care I have to take is to emphasize the variance. In this case I think we have got a 50-50 chance of getting to that tipping point in mice within five years from now, certainly it could be 10 or 15 years if we get unlucky. Similarly, for humans, a 50-50 chance would be twenty years at this point, and there's a 10 percent chance that we won't get there for a hundred years.

"I don't get people coming to me saying, well I don't think medicine for the elderly should be done because if it worked it would be a bad thing. People like to ignore this contradiction."

What would you tell skeptical people are the biggest benefits of a very long-lived population?

Any question about the longevity of people is the wrong question. Because the longevity that people fixate about so much will only ever occur as a side effect of health. However long ago you were born or however recently, if you're sick, you're likely to die fairly soon unless we can stop you being sick. Whereas if you're healthy, you're not. So if we do as well as we think we can do in terms of keeping people healthy and youthful however long ago they were born, then the side effect in terms of longevity and life expectancy is likely to be very large. But it's still a side effect, so the way that people actually ought to be—in fact have a requirement to be—thinking, is about whether they want people to be healthy.

Now I don't get people coming to me saying, well I don't think medicine for the elderly should be done because if it worked it would be a bad thing. People like to ignore this contradiction, they like to sweep it under the carpet and say, oh yeah, aging is totally a good thing.

People will never actually admit to the fact that what they are fundamentally saying is medicine for the elderly, if it actually works, would be bad, but still that is what they are saying.

Shifting gears a bit, I'm curious to find out which other radical visionaries in science and tech today you most admire?

Fair question. One is Mike West. I have the great privilege that I now work for him part-time with Age X. I have looked up to him very much for the past ten years, because what he did over the past 20 years starting with Geron is unimaginable today. He was working in an environment where I would not have dreamt of the possibility of getting any private money, any actual investment, in something that far out, that far ahead of its time, and he did it, again and again. It's insane what he managed to do.

What about someone like Elon Musk?

Sure, he's another one. He is totally impervious to the caution and criticism and conservatism that pervades humanity, and he's getting on making these bloody self-driving cars, space tourism, and so on, making them happen. He's thinking just the way I'm thinking really.

"You can just choose how frequently and how thoroughly you repair the damage. And you can make a different choice next time."

You famously said ten years ago that you think the first person to live to 1000 is already alive. Do you think that's still the case?

Definitely, yeah. I can't see how it could not be. Again, it's a probabilistic thing. I said there's at least a 10 percent chance that we won't get to what I call Longevity Escape Velocity for 100 years and if that's true, then the statement about 1000 years being alive already is not going to be the case. But for sure, I believe that the beneficiaries of what we may as well call SENS 1.0, the point where we get to LEV, those people are exceptionally unlikely ever to suffer from any kind of ill health correlated with their age. Because we will never fall below Longevity Escape Velocity once we attain it.

Could someone who was just born today expect—

I would say people in middle age now have a fair chance. Remember – a 50/50 chance of getting to LEV within 20 years, and when you get there, you don't just stay at biologically 70 or 80, you are rejuvenated back to biologically 30 or 40 and you stay there, so your risk of death each year is not related to how long ago you were born, it's the same as a young adult. Today, that's less than 1 in 1000 per year, and that number is going to go down as we get self-driving cars and all that, so actually 1000 is a very conservative number.

So you would be able to choose what age you wanted to go back to?

Oh sure, of course, it's just like a car. What you're doing is you're repairing damage, and the damage is still being created by the body's metabolism, so you can just choose how frequently and how thoroughly you repair the damage. And you can make a different choice next time.

What would be your perfect age?

I have no idea. That's something I don't have an opinion about, because I could change it whenever I like.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A company has slashed the cost of assessing a person's genome to just $100. With lower costs - and as other genetic tools mature and evolve - a wave of new therapies could be coming in the near future.

In May 2022, Californian biotech Ultima Genomics announced that its UG 100 platform was capable of sequencing an entire human genome for just $100, a landmark moment in the history of the field. The announcement was particularly remarkable because few had previously heard of the company, a relative unknown in an industry long dominated by global giant Illumina which controls about 80 percent of the world’s sequencing market.

Ultima’s secret was to completely revamp many technical aspects of the way Illumina have traditionally deciphered DNA. The process usually involves first splitting the double helix DNA structure into single strands, then breaking these strands into short fragments which are laid out on a glass surface called a flow cell. When this flow cell is loaded into the sequencing machine, color-coded tags are attached to each individual base letter. A laser scans the bases individually while a camera simultaneously records the color associated with them, a process which is repeated until every single fragment has been sequenced.

Instead, Ultima has found a series of shortcuts to slash the cost and boost efficiency. “Ultima Genomics has developed a fundamentally new sequencing architecture designed to scale beyond conventional approaches,” says Josh Lauer, Ultima’s chief commercial officer.

This ‘new architecture’ is a series of subtle but highly impactful tweaks to the sequencing process ranging from replacing the costly flow cell with a silicon wafer which is both cheaper and allows more DNA to be read at once, to utilizing machine learning to convert optical data into usable information.

To put $100 genome in perspective, back in 2012 the cost of sequencing a single genome was around $10,000, a price tag which dropped to $1,000 a few years later. Before Ultima’s announcement, the cost of sequencing an individual genome was around $600.

Several studies have found that nearly 12 percent of healthy people who have their genome sequenced, then discover they have a variant pointing to a heightened risk of developing a disease that can be monitored, treated or prevented.

While Ultima’s new machine is not widely available yet, Illumina’s response has been rapid. In September 2022, the company unveiled the NovaSeq X series, which it describes as its fastest most cost-efficient sequencing platform yet, capable of sequencing genomes at $200, with further price cuts likely to follow.

But what will the rapidly tumbling cost of sequencing actually mean for medicine? “Well to start with, obviously it’s going to mean more people getting their genome sequenced,” says Michael Snyder, professor of genetics at Stanford University. “It'll be a lot more accessible to people.”

At the moment sequencing is mainly limited to certain cancer patients where it is used to inform treatment options, and individuals with undiagnosed illnesses. In the past, initiatives such as SeqFirst have attempted further widen access to genome sequencing based on growing amounts of research illustrating the potential benefits of the technology in healthcare. Several studies have found that nearly 12 percent of healthy people who have their genome sequenced, then discover they have a variant pointing to a heightened risk of developing a disease that can be monitored, treated or prevented.

“While whole genome sequencing is not yet widely used in the U.S., it has started to come into pediatric critical care settings such as newborn intensive care units,” says Professor Michael Bamshad, who heads the genetic medicine division in the University of Washington’s pediatrics department. “It is also being used more often in outpatient clinical genetics services, particularly when conventional testing fails to identify explanatory variants.”

But the cost of sequencing itself is only one part of the price tag. The subsequent clinical interpretation and genetic counselling services often come to several thousand dollars, a cost which insurers are not always willing to pay.

As a result, while Bamshad and others hope that the arrival of the $100 genome will create new opportunities to use genetic testing in innovative ways, the most immediate benefits are likely to come in the realm of research.

Bigger Data

There are numerous ways in which cheaper sequencing is likely to advance scientific research, for example the ability to collect data on much larger patient groups. This will be a major boon to scientists working on complex heterogeneous diseases such as schizophrenia or depression where there are many genes involved which all exert subtle effects, as well as substantial variance across the patient population. Bigger studies could help scientists identify subgroups of patients where the disease appears to be driven by similar gene variants, who can then be more precisely targeted with specific drugs.

If insurers can figure out the economics, Snyder even foresees a future where at a certain age, all of us can qualify for annual sequencing of our blood cells to search for early signs of cancer or the potential onset of other diseases like type 2 diabetes.

David Curtis, a genetics professor at University College London, says that scientists studying these illnesses have previously been forced to rely on genome-wide association studies which are limited because they only identify common gene variants. “We might see a significant increase in the number of large association studies using sequence data,” he says. “It would be far preferable to use this because it provides information about rare, potentially functional variants.”

Cheaper sequencing will also aid researchers working on diseases which have traditionally been underfunded. Bamshad cites cystic fibrosis, a condition which affects around 40,000 children and adults in the U.S., as one particularly pertinent example.

“Funds for gene discovery for rare diseases are very limited,” he says. “We’re one of three sites that did whole genome sequencing on 5,500 people with cystic fibrosis, but our statistical power is limited. A $100 genome would make it much more feasible to sequence everyone in the U.S. with cystic fibrosis and make it more likely that we discover novel risk factors and pathways influencing clinical outcomes.”

For progressive diseases that are more common like cancer and type 2 diabetes, as well as neurodegenerative conditions like multiple sclerosis and ALS, geneticists will be able to go even further and afford to sequence individual tumor cells or neurons at different time points. This will enable them to analyze how individual DNA modifications like methylation, change as the disease develops.

In the case of cancer, this could help scientists understand how tumors evolve to evade treatments. Within in a clinical setting, the ability to sequence not just one, but many different cells across a patient’s tumor could point to the combination of treatments which offer the best chance of eradicating the entire cancer.

“What happens at the moment with a solid tumor is you treat with one drug, and maybe 80 percent of that tumor is susceptible to that drug,” says Neil Ward, vice president and general manager in the EMEA region for genomics company PacBio. “But the other 20 percent of the tumor has already got mutations that make it resistant, which is probably why a lot of modern therapies extend life for sadly only a matter of months rather than curing, because they treat a big percentage of the tumor, but not the whole thing. So going forwards, I think that we will see genomics play a huge role in cancer treatments, through using multiple modalities to treat someone's cancer.”

If insurers can figure out the economics, Snyder even foresees a future where at a certain age, all of us can qualify for annual sequencing of our blood cells to search for early signs of cancer or the potential onset of other diseases like type 2 diabetes.

“There are companies already working on looking for cancer signatures in methylated DNA,” he says. “If it was determined that you had early stage cancer, pre-symptomatically, that could then be validated with targeted MRI, followed by surgery or chemotherapy. It makes a big difference catching cancer early. If there were signs of type 2 diabetes, you could start taking steps to mitigate your glucose rise, and possibly prevent it or at least delay the onset.”

This would already revolutionize the way we seek to prevent a whole range of illnesses, but others feel that the $100 genome could also usher in even more powerful and controversial preventative medicine schemes.

Newborn screening

In the eyes of Kári Stefánsson, the Icelandic neurologist who been a visionary for so many advances in the field of human genetics over the last 25 years, the falling cost of sequencing means it will be feasible to sequence the genomes of every baby born.

“We have recently done an analysis of genomes in Iceland and the UK Biobank, and in 4 percent of people you find mutations that lead to serious disease, that can be prevented or dealt with,” says Stefansson, CEO of deCODE genetics, a subsidiary of the pharmaceutical company Amgen. “This could transform our healthcare systems.”

As well as identifying newborns with rare diseases, this kind of genomic information could be used to compute a person’s risk score for developing chronic illnesses later in life. If for example, they have a higher than average risk of colon or breast cancer, they could be pre-emptively scheduled for annual colonoscopies or mammograms as soon as they hit adulthood.

To a limited extent, this is already happening. In the UK, Genomics England has launched the Newborn Genomes Programme, which plans to undertake whole-genome sequencing of up to 200,000 newborn babies, with the aim of enabling the early identification of rare genetic diseases.

"I have not had my own genome sequenced and I would not have wanted my parents to have agreed to this," Curtis says. "I don’t see that sequencing children for the sake of some vague, ill-defined benefits could ever be justifiable.”

However, some scientists feel that it is tricky to justify sequencing the genomes of apparently healthy babies, given the data privacy issues involved. They point out that we still know too little about the links which can be drawn between genetic information at birth, and risk of chronic illness later in life.

“I think there are very difficult ethical issues involved in sequencing children if there are no clear and immediate clinical benefits,” says Curtis. “They cannot consent to this process. I have not had my own genome sequenced and I would not have wanted my parents to have agreed to this. I don’t see that sequencing children for the sake of some vague, ill-defined benefits could ever be justifiable.”

Curtis points out that there are many inherent risks about this data being available. It may fall into the hands of insurance companies, and it could even be used by governments for surveillance purposes.

“Genetic sequence data is very useful indeed for forensic purposes. Its full potential has yet to be realized but identifying rare variants could provide a quick and easy way to find relatives of a perpetrator,” he says. “If large numbers of people had been sequenced in a healthcare system then it could be difficult for a future government to resist the temptation to use this as a resource to investigate serious crimes.”

While sequencing becoming more widely available will present difficult ethical and moral challenges, it will offer many benefits for society as a whole. Cheaper sequencing will help boost the diversity of genomic datasets which have traditionally been skewed towards individuals of white, European descent, meaning that much of the actionable medical information which has come out of these studies is not relevant to people of other ethnicities.

Ward predicts that in the coming years, the growing amount of genetic information will ultimately change the outcomes for many with rare, previously incurable illnesses.

“If you're the parent of a child that has a susceptible or a suspected rare genetic disease, their genome will get sequenced, and while sadly that doesn’t always lead to treatments, it’s building up a knowledge base so companies can spring up and target that niche of a disease,” he says. “As a result there’s a whole tidal wave of new therapies that are going to come to market over the next five years, as the genetic tools we have, mature and evolve.”

This article was first published by Leaps.org in October 2022.

Sharing land and other resources among farmers isn’t new. But research shows it may be increasingly relevant in a time of climatic upheaval.

The livestock trucks arrived all night. One after the other they backed up to the wood chute leading to a dusty corral and loosed their cargo — 580 head of cattle by the time the last truck pulled away at 3pm the next afternoon. Dan Probert, astride his horse, guided the cows to paddocks of pristine grassland stretching alongside the snow-peaked Wallowa Mountains. They’d spend the summer here grazing bunchgrass and clovers and biscuitroot. The scuffle of their hooves and nibbles of their teeth would mimic the elk, antelope and bison that are thought to have historically roamed this portion of northeastern Oregon’s Zumwalt Prairie, helping grasses grow and restoring health to the soil.

The cows weren’t Probert’s, although the fifth-generation rancher and one other member of the Carman Ranch Direct grass-fed beef collective also raise their own herds here for part of every year. But in spring, when the prairie is in bloom, Probert receives cattle from several other ranchers. As the grasses wither in October, the cows move on to graze fertile pastures throughout the Columbia Basin, which stretches across several Pacific Northwest states; some overwinter on a vegetable farm in central Washington, feeding on corn leaves and pea vines left behind after harvest.

Sharing land and other resources among farmers isn’t new. But research shows it may be increasingly relevant in a time of climatic upheaval, potentially influencing “farmers to adopt environmentally friendly practices and agricultural innovation,” according to a 2021 paper in the Journal of Economic Surveys. Farmers might share knowledge about reducing pesticide use, says Heather Frambach, a supply chain consultant who works with farmers in California and elsewhere. As a group they may better qualify for grants to monitor soil and water quality.

Most research around such practices applies to cooperatives, whose owner-members equally share governance and profits. But a collective like Carman Ranch’s — spearheaded by fourth-generation rancher Cory Carman, who purchases beef from eight other ranchers to sell under one “regeneratively” certified brand — shows when producers band together, they can achieve eco-benefits that would be elusive if they worked alone.

Vitamins and minerals in soil pass into plants through their roots, then into cattle as they graze, then back around as the cows walk around pooping.

Carman knows from experience. Taking over her family's land in 2003, she started selling grass-fed beef “because I really wanted to figure out how to not participate in the feedlot world, to have a healthier product. I didn't know how we were going to survive,” she says. Part of her land sits on a degraded portion of Zumwalt Prairie replete with invasive grasses; working to restore it, she thought, “What good does it do to kill myself trying to make this ranch more functional? If you want to make a difference, change has to be more than single entrepreneurs on single pieces of land. It has to happen at a community level.” The seeds of her collective were sown.

Raising 100 percent grass-fed beef requires land that’s got something for cows to graze in every season — which most collective members can’t access individually. So, they move cattle around their various parcels. It’s practical, but it also restores nutrient flows “to the way they used to move, from lowlands and canyons during the winter to higher-up places as the weather gets hot,” Carman says. Meaning, vitamins and minerals in soil pass into plants through their roots, then into cattle as they graze, then back around as the cows walk around pooping.

Cory Carman sells grass-fed beef, which requires land that’s got something for cows to graze in every season.

Courtesy Cory Carman

Each collective member has individual ecological goals: Carman brought in pigs to root out invasive grasses and help natives flourish. Probert also heads a more conventional grain-finished beef collective with 100 members, and their combined 6.5 million ranchland acres were eligible for a grant supporting climate-friendly practices, which compels them to improve soil and water health and biodiversity and make their product “as environmentally friendly as possible,” Probert says. The Washington veg farmer reduced tilling and pesticide use thanks to the ecoservices of visiting cows. Similarly, a conventional hay farmer near Carman has reduced his reliance on fertilizer by letting cattle graze the cover crops he plants on 80 acres.

Additionally, the collective must meet the regenerative standards promised on their label — another way in which they work together to achieve ecological goals. Says David LeZaks, formerly a senior fellow at finance-focused ecology nonprofit Croatan Institute, it’s hard for individual farmers to access monetary assistance. “But it's easier to get financing flowing when you increase the scale with cooperatives or collectives,” he says. “This supports producers in ways that can lead to better outcomes on the landscape.”

New, smaller scale farmers might gain the most from collective and cooperative models.

For example, it can help them minimize waste by using more of an animal, something our frugal ancestors excelled at. Small-scale beef producers normally throw out hides; Thousand Hills’ 50 regenerative beef producers together have enough to sell to Timberland to make carbon-neutral leather. In another example, working collectively resulted in the support of more diverse farms: Meadowlark Community Mill in Wisconsin went from working with one wheat grower, to sourcing from several organic wheat growers marketing flour under one premium brand.

Another example shows how these collaborations can foster greater equity, among other benefits: The Federation of Southern Cooperatives has a mission to support Black farmers as they build community health. It owns several hundred forest acres in Alabama, where it teaches members to steward their own forest land and use it to grow food — one member coop raises goats to graze forest debris and produce milk. Adding the combined acres of member forest land to the Federation’s, the group qualified for a federal conservation grant that will keep this resource available for food production, and community environmental and mental health benefits. “That's the value-add of the collective land-owner structure,” says Dãnia Davy, director of land retention and advocacy.

New, smaller scale farmers might gain the most from collective and cooperative models, says Jordan Treakle, national program coordinator of the National Family Farm Coalition (NFFC). Many of them enter farming specifically to raise healthy food in healthy ways — with organic production, or livestock for soil fertility. With land, equipment and labor prohibitively expensive, farming collectively allows shared costs and risk that buy farmers the time necessary to “build soil fertility and become competitive” in the marketplace, Treakle says. Just keeping them in business is an eco-win; when small farms fail, they tend to get sold for development or absorbed into less-diversified operations, so the effects of their success can “reverberate through the entire local economy.”

Frambach, the supply chain consultant, has been experimenting with what she calls “collaborative crop planning,” where she helps farmers strategize what they’ll plant as a group. “A lot of them grow based on what they hear their neighbor is going to do, and that causes really poor outcomes,” she says. “Nobody replanted cauliflower after the [atmospheric rivers in California] this year and now there's a huge shortage of cauliflower.” A group plan can avoid the under-planting that causes farmers to lose out on revenue.

It helps avoid overplanted crops, too, which small farmers might have to plow under or compost. Larger farmers, conversely, can sell surplus produce into the upcycling market — to Matriark Foods, for example, which turns it into value-add products like pasta sauce for companies like Sysco that supply institutional kitchens at colleges and hospitals. Frambach and Anna Hammond, Matriark’s CEO, want to collectivize smaller farmers so that they can sell to the likes of Matriark and “not lose an incredible amount of income,” Hammond says.

Ultimately, farming is fraught with challenges and even collectivizing doesn’t guarantee that farms will stay in business. But with agriculture accounting for almost 30 percent of greenhouse gas emissions globally, there's an “urgent” need to shift farming practices to more environmentally sustainable models, as well as a “demand in the marketplace for it,” says NFFC’s Treakle. “The growth of cooperative and collective farming can be a huge, huge boon for the ecological integrity of the system.”