Scientists redesign bacteria to tackle the antibiotic resistance crisis

Probiotic bacteria can be engineered to fight antibiotic-resistant superbugs by releasing chemicals that kill them.

In 1945, almost two decades after Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, he warned that as antibiotics use grows, they may lose their efficiency. He was prescient—the first case of penicillin resistance was reported two years later. Back then, not many people paid attention to Fleming’s warning. After all, the “golden era” of the antibiotics age had just began. By the 1950s, three new antibiotics derived from soil bacteria — streptomycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline — could cure infectious diseases like tuberculosis, cholera, meningitis and typhoid fever, among others.

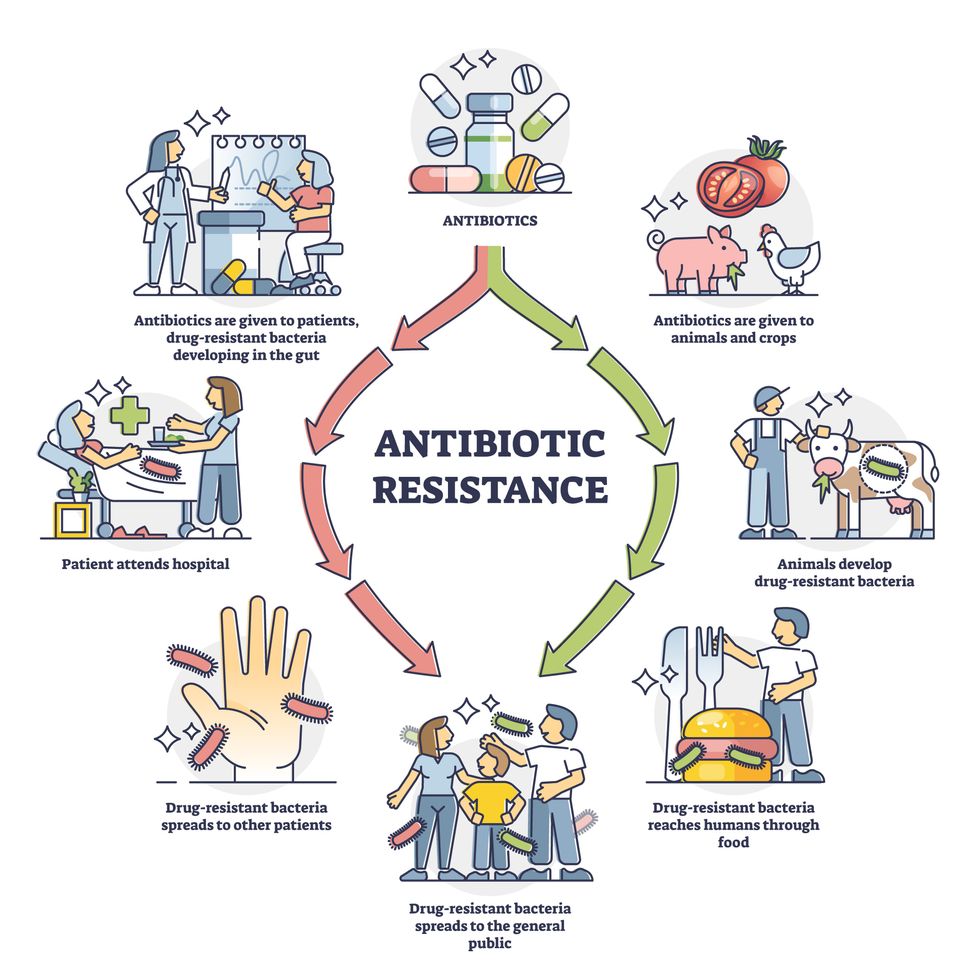

Today, these antibiotics and many of their successors developed through the 1980s are gradually losing their effectiveness. The extensive overuse and misuse of antibiotics led to the rise of drug resistance. The livestock sector buys around 80 percent of all antibiotics sold in the U.S. every year. Farmers feed cows and chickens low doses of antibiotics to prevent infections and fatten up the animals, which eventually causes resistant bacterial strains to evolve. If manure from cattle is used on fields, the soil and vegetables can get contaminated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Another major factor is doctors overprescribing antibiotics to humans, particularly in low-income countries. Between 2000 to 2018, the global rates of human antibiotic consumption shot up by 46 percent.

In recent years, researchers have been exploring a promising avenue: the use of synthetic biology to engineer new bacteria that may work better than antibiotics. The need continues to grow, as a Lancet study linked antibiotic resistance to over 1.27 million deaths worldwide in 2019, surpassing HIV/AIDS and malaria. The western sub-Saharan Africa region had the highest death rate (27.3 people per 100,000).

Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

To make it worse, our remedy pipelines are drying up. Out of the 18 biggest pharmaceutical companies, 15 abandoned antibiotic development by 2013. According to the AMR Action Fund, venture capital has remained indifferent towards biotech start-ups developing new antibiotics. In 2019, at least two antibiotic start-ups filed for bankruptcy. As of December 2020, there were 43 new antibiotics in clinical development. But because they are based on previously known molecules, scientists say they are inadequate for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria. Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

The rise of synthetic biology

To circumvent this dire future, scientists have been working on alternative solutions using synthetic biology tools, meaning genetically modifying good bacteria to fight the bad ones.

From the time life evolved on earth around 3.8 billion years ago, bacteria have engaged in biological warfare. They constantly strategize new methods to combat each other by synthesizing toxic proteins that kill competition.

For example, Escherichia coli produces bacteriocins or toxins to kill other strains of E.coli that attempt to colonize the same habitat. Microbes like E.coli (which are not all pathogenic) are also naturally present in the human microbiome. The human microbiome harbors up to 100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells. The majority of them are beneficial organisms residing in the gut at different compositions.

The chemicals that these “good bacteria” produce do not pose any health risks to us, but can be toxic to other bacteria, particularly to human pathogens. For the last three decades, scientists have been manipulating bacteria’s biological warfare tactics to our collective advantage.

In the late 1990s, researchers drew inspiration from electrical and computing engineering principles that involve constructing digital circuits to control devices. In certain ways, every cell in living organisms works like a tiny computer. The cell receives messages in the form of biochemical molecules that cling on to its surface. Those messages get processed within the cells through a series of complex molecular interactions.

Synthetic biologists can harness these living cells’ information processing skills and use them to construct genetic circuits that perform specific instructions—for example, secrete a toxin that kills pathogenic bacteria. “Any synthetic genetic circuit is merely a piece of information that hangs around in the bacteria’s cytoplasm,” explains José Rubén Morones-Ramírez, a professor at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Mexico. Then the ribosome, which synthesizes proteins in the cell, processes that new information, making the compounds scientists want bacteria to make. “The genetic circuit remains separated from the living cell’s DNA,” Morones-Ramírez explains. When the engineered bacteria replicates, the genetic circuit doesn’t become part of its genome.

Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut.

In 2000, Boston-based researchers constructed an E.coli with a genetic switch that toggled between turning genes on and off two. Later, they built some safety checks into their bacteria. “To prevent unintentional or deleterious consequences, in 2009, we built a safety switch in the engineered bacteria’s genetic circuit that gets triggered after it gets exposed to a pathogen," says James Collins, a professor of biological engineering at MIT and faculty member at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute. “After getting rid of the pathogen, the engineered bacteria is designed to switch off and leave the patient's body.”

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics causes resistant strains to evolve

Adobe Stock

Seek and destroy

As the field of synthetic biology developed, scientists began using engineered bacteria to tackle superbugs. They first focused on Vibrio cholerae, which in the 19th and 20th century caused cholera pandemics in India, China, the Middle East, Europe, and Americas. Like many other bacteria, V. cholerae communicate with each other via quorum sensing, a process in which the microorganisms release different signaling molecules, to convey messages to its brethren. Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut. When untreated, cholera has a mortality rate of 25 to 50 percent and outbreaks frequently occur in developing countries, especially during floods and droughts.

Sometimes, however, V. cholerae makes mistakes. In 2008, researchers at Cornell University observed that when quorum sensing V. cholerae accidentally released high concentrations of a signaling molecule called CAI-1, it had a counterproductive effect—the pathogen couldn’t colonize the gut.

So the group, led by John March, professor of biological and environmental engineering, developed a novel strategy to combat V. cholerae. They genetically engineered E.coli to eavesdrop on V. cholerae communication networks and equipped it with the ability to release the CAI-1 molecules. That interfered with V. cholerae progress. Two years later, the Cornell team showed that V. cholerae-infected mice treated with engineered E.coli had a 92 percent survival rate.

These findings inspired researchers to sic the good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi onto the drug-resistant ones.

Three years later in 2011, Singapore-based scientists engineered E.coli to detect and destroy Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an often drug-resistant pathogen that causes pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis. Once the genetically engineered E.coli found its target through its quorum sensing molecules, it then released a peptide, that could eradicate 99 percent of P. aeruginosa cells in a test-tube experiment. The team outlined their work in a Molecular Systems Biology study.

“At the time, we knew that we were entering new, uncharted territory,” says lead author Matthew Chang, an associate professor and synthetic biologist at the National University of Singapore and lead author of the study. “To date, we are still in the process of trying to understand how long these microbes stay in our bodies and how they might continue to evolve.”

More teams followed the same path. In a 2013 study, MIT researchers also genetically engineered E.coli to detect P. aeruginosa via the pathogen’s quorum-sensing molecules. It then destroyed the pathogen by secreting a lab-made toxin.

Probiotics that fight

A year later in 2014, a Nature study found that the abundance of Ruminococcus obeum, a probiotic bacteria naturally occurring in the human microbiome, interrupts and reduces V.cholerae’s colonization— by detecting the pathogen’s quorum sensing molecules. The natural accumulation of R. obeum in Bangladeshi adults helped them recover from cholera despite living in an area with frequent outbreaks.

The findings from 2008 to 2014 inspired Collins and his team to delve into how good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi can attack drug-resistant bacteria. In 2018, Collins and his team developed the engineered probiotic strategy. They tweaked a bacteria commonly found in yogurt called Lactococcus lactis to treat cholera.

Engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut. --José Rubén Morones-Ramírez.

More scientists followed with more experiments. So far, researchers have engineered various probiotic organisms to fight pathogenic bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus (leading cause of skin, tissue, bone, joint and blood infections) and Clostridium perfringens (which causes watery diarrhea) in test-tube and animal experiments. In 2020, Russian scientists engineered a probiotic called Pichia pastoris to produce an enzyme called lysostaphin that eradicated S. aureus in vitro. Another 2020 study from China used an engineered probiotic bacteria Lactobacilli casei as a vaccine to prevent C. perfringens infection in rabbits.

In a study last year, Ramírez’s group at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, engineered E. coli to detect quorum-sensing molecules from Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA, a notorious superbug. The E. coli then releases a bacteriocin that kills MRSA. “An antibiotic is just a molecule that is not intelligent,” says Ramírez. “On the other hand, engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut.”

Collins and Timothy Lu, an associate professor of biological engineering at MIT, found that engineered E. coli can help treat other conditions—such as phenylketonuria, a rare metabolic disorder, that causes the build-up of an amino acid phenylalanine. Their start-up Synlogic aims to commercialize the technology, and has completed a phase 2 clinical trial.

Circumventing the challenges

The bacteria-engineering technique is not without pitfalls. One major challenge is that beneficial gut bacteria produce their own quorum-sensing molecules that can be similar to those that pathogens secrete. If an engineered bacteria’s biosensor is not specific enough, it will be ineffective.

Another concern is whether engineered bacteria might mutate after entering the gut. “As with any technology, there are risks where bad actors could have the capability to engineer a microbe to act quite nastily,” says Collins of MIT. But Collins and Ramírez both insist that the chances of the engineered bacteria mutating on its own are virtually non-existent. “It is extremely unlikely for the engineered bacteria to mutate,” Ramírez says. “Coaxing a living cell to do anything on command is immensely challenging. Usually, the greater risk is that the engineered bacteria entirely lose its functionality.”

However, the biggest challenge is bringing the curative bacteria to consumers. Pharmaceutical companies aren’t interested in antibiotics or their alternatives because it’s less profitable than developing new medicines for non-infectious diseases. Unlike the more chronic conditions like diabetes or cancer that require long-term medications, infectious diseases are usually treated much quicker. Running clinical trials are expensive and antibiotic-alternatives aren’t lucrative enough.

“Unfortunately, new medications for antibiotic resistant infections have been pushed to the bottom of the field,” says Lu of MIT. “It's not because the technology does not work. This is more of a market issue. Because clinical trials cost hundreds of millions of dollars, the only solution is that governments will need to fund them.” Lu stresses that societies must lobby to change how the modern healthcare industry works. “The whole world needs better treatments for antibiotic resistance.”

Fungus is the ‘New Black’ in Eco-Friendly Fashion

On the left, a Hermès bag made using fine mycelium as a leather alternative, made in partnership with the biotech company MycoWorks; on right, a sheet of mycelium "leather."

A natural material that looks and feels like real leather is taking the fashion world by storm. Scientists view mycelium—the vegetative part of a mushroom-producing fungus—as a planet-friendly alternative to animal hides and plastics.

Products crafted from this vegan leather are emerging, with others poised to hit the market soon. Among them are the Hermès Victoria bag, Lululemon's yoga accessories, Adidas' Stan Smith Mylo sneaker, and a Stella McCartney apparel collection.

The Adidas' Stan Smith Mylo concept sneaker, made in partnership with Bolt Threads, uses an alternative leather grown from mycelium; a commercial version is expected in the near future.

Adidas

Hermès has held presales on the new bag, says Philip Ross, co-founder and chief technology officer of MycoWorks, a San Francisco Bay area firm whose materials constituted the design. By year-end, Ross expects several more clients to debut mycelium-based merchandise. With "comparable qualities to luxury leather," mycelium can be molded to engineer "all the different verticals within fashion," he says, particularly footwear and accessories.

More than a half-dozen trailblazers are fine-tuning mycelium to create next-generation leather materials, according to the Material Innovation Initiative, a nonprofit advocating for animal-free materials in the fashion, automotive, and home-goods industries. These high-performance products can supersede items derived from leather, silk, down, fur, wool, and exotic skins, says A. Sydney Gladman, the institute's chief scientific officer.

That's only the beginning of mycelium's untapped prowess. "We expect to see an uptick in commercial leather alternative applications for mycelium-based materials as companies refine their R&D [research and development] and scale up," Gladman says, adding that "technological innovation and untapped natural materials have the potential to transform the materials industry and solve the enormous environmental challenges it faces."

In fewer than 10 days in indoor agricultural farms, "we grow large slabs of mycelium that are many feet wide and long. We are not confined to the shape or geometry of an animal."

Reducing our carbon footprint becomes possible because mycelium can flourish in indoor farms, using agricultural waste as feedstock and emitting inherently low greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon dioxide is the primary greenhouse gas. "We often think that when plant tissues like wood rot, that they go from something to nothing," says Jonathan Schilling, professor of plant and microbial biology at the University of Minnesota and a member of MycoWorks' Scientific Advisory Board.

But that assumption doesn't hold true for all carbon in plant tissues. When the fungi dominating the decomposition of plants fulfill their function, they transform a large portion of carbon into fungal biomass, Schilling says. That, in turn, ends up in the soil, with mycelium forming a network underneath that traps the carbon.

Unlike the large amounts of fossil fuels needed to produce styrofoam, leather and plastic, less fuel-intensive processing is involved in creating similar materials with a fungal organism. While some fungi consist of a single cell, others are multicellular and develop as very fine threadlike structures. A mass of them collectively forms a "mycelium" that can be either loose and low density or tightly packed and high density. "When these fungi grow at extremely high density," Schilling explains, "they can take on the feel of a solid material such as styrofoam, leather or even plastic."

Tunable and supple in the cultivation process, mycelium is also reliably sturdy in composition. "We believe that mycelium has some unique attributes that differentiate it from plastic-based and animal-derived products," says Gavin McIntyre, who co-founded Ecovative Design, an upstate New York-based biomaterials company, in 2007 with the goal of displacing some environmentally burdensome materials and making "a meaningful impact on our planet."

After inventing a type of mushroom-based packaging for all sorts of goods, in 2013 the firm ventured into manufacturing mycelium that can be adapted for textiles, he says, because mushrooms are "nature's recycling system."

The company aims for its material—which is "so tough and tenacious" that it doesn't require any plastic add-on as reinforcement—to be generally accessible from a pricing standpoint and not confined to a luxury space. The cost, McIntyre says, would approach that of bovine leather, not the more upscale varieties of lamb and goat skins.

Already, production has taken off by leaps and bounds. In fewer than 10 days in indoor agricultural farms, "we grow large slabs of mycelium that are many feet wide and long," he says. "We are not confined to the shape or geometry of an animal," so there's a much lower scrap rate.

Decreasing the scrap rate is a major selling point. "Our customers can order the pieces to the way that they want them, and there is almost no waste in the processing," explains Ross of MycoWorks. "We can make ours thinner or thicker," depending on a client's specific needs. Growing materials locally also results in a reduction in transportation, shipping, and other supply chain costs, he says.

Yet another advantage to making things out of mycelium is its biodegradability at the end of an item's lifecycle. When a pair of old sneakers lands in a compost pile or landfill, it decomposes thanks to microbial processes that, once again, involve fungi. "It is cool to think that the same organism used to create a product can also be what recycles it, perhaps building something else useful in the same act," says biologist Schilling. That amounts to "more than a nice business model—it is a window into how sustainability works in nature."

A product can be called "sustainable" if it's biodegradable, leaves a minimal carbon footprint during production, and is also profitable, says Preeti Arya, an assistant professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City and faculty adviser to a student club of the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, products composed of petroleum-based polymers don't biodegrade—they break down into smaller pieces or even particles. These remnants pollute landfills, oceans, and rivers, contaminating edible fish and eventually contributing to the growth of benign and cancerous tumors in humans, Arya says.

Commending the steps a few designers have taken toward bringing more environmentally conscious merchandise to consumers, she says, "I'm glad that they took the initiative because others also will try to be part of this competition toward sustainability." And consumers will take notice. "The more people become aware, the more these brands will start acting on it."

A further shift toward mycelium-based products has the capability to reap tremendous environmental dividends, says Drew Endy, associate chair of bioengineering at Stanford University and president of the BioBricks Foundation, which focuses on biotechnology in the public interest.

The continued development of "leather surrogates on a scaled and sustainable basis will provide the greatest benefit to the greatest number of people, in perpetuity," Endy says. "Transitioning the production of leather goods from a process that involves the industrial-scale slaughter of vertebrate mammals to a process that instead uses renewable fungal-based manufacturing will be more just."

Can Biotechnology Take the Allergies Out of Cats?

From a special food to a vaccine and gene editing, new technologies may offer solutions for cat lovers with allergies.

Amy Bitterman, who teaches at Rutgers Law School in Newark, gets enormous pleasure from her three mixed-breed rescue cats, Spike, Dee, and Lucy. To manage her chronically stuffy nose, three times a week she takes Allegra D, which combines the antihistamine fexofenadine with the decongestant pseudoephedrine. Amy's dog allergy is rougher--so severe that when her sister launched a business, Pet Care By Susan, from their home in Edison, New Jersey, they knew Susan would have to move elsewhere before she could board dogs. Amy has tried to visit their brother, who owns a Labrador Retriever, taking Allegra D beforehand. But she began sneezing, and then developed watery eyes and phlegm in her chest.

"It gets harder and harder to breathe," she says.

Animal lovers have long dreamed of "hypo-allergenic" cats and dogs. Although to date, there is no such thing, biotechnology is beginning to provide solutions for cat-lovers. Cats are a simpler challenge than dogs. Dog allergies involve as many as seven proteins. But up to 95 percent of people who have cat allergies--estimated at 10 to 30 percent of the population in North America and Europe--react to one protein, Fel d1. Interestingly, cats don't seem to need Fel d1. There are cats who don't produce much Fel d1 and have no known health problems.

The current technologies fight Fel d1 in ingenious ways. Nestle Purina reached the market first with a cat food, Pro Plan LiveClear, launched in the U.S. a year and a half ago. It contains Fel d1 antibodies from eggs that in effect neutralize the protein. HypoCat, a vaccine for cats, induces them to create neutralizing antibodies to their own Fel d1. It may be available in the United States by 2024, says Gary Jennings, chief executive officer of Saiba Animal Health, a University of Zurich spin-off. Another approach, using the gene-editing tool CRISPR to create a medication that would splice out Fel d1 genes in particular tissues, is the furthest from fruition.

"Our goal was to ensure that whatever we do has no negative impact on the cat."

Customer demand is high. "We already have a steady stream of allergic cat owners contacting us desperate to have access to the vaccine or participate in the testing program," Jennings said. "There is a major unmet medical need."

More than a third of Americans own a cat (while half own a dog), and pet ownership is rising. With more Americans living alone, pets may be just the right amount of company. But the number of Americans with asthma increases every year. Of that group, some 20 to 30 percent have pet allergies that could trigger a possibly deadly attack. It is not clear how many pets end up in shelters because their owners could no longer manage allergies. Instead, allergists commonly report that their patients won't give up a beloved companion.

No one can completely avoid Fel d1, which clings to clothing and lands everywhere cat-owners go, even in schools and new homes never occupied by cats. Myths among cat-lovers may lead them to underestimate their own level of risk. Short hair doesn't help: the length of cat hair doesn't affect the production of Fel d1. Bathing your cat will likely upset it and accomplish little. Washing cuts the amount on its skin and fur only for two days. In one study, researchers measured the Fel d1 in the ambient air in a small chamber occupied by a cat—and then washed the cat. Three hours later, with the cat in the chamber again, the measurable Fel d1 in the air was lower. But this benefit was gone after 24 hours.

For years, the best option has been shots for people that prompt protective antibodies. Bitterman received dog and cat allergy injections twice a week as a child. However, these treatments require up to 100 injections over three to five years, and, as in her case, the effect may be partial or wear off. Even if you do opt for shots, treating the cat also makes sense, since you could protect more than one allergic member of your household and any allergic visitors as well.

An Allergy-Neutralizing Diet

Cats produce much of their Fel d1 in their saliva, which then spreads it to their fur when they groom, observed Nestle Purina immunologist Ebenezer Satyaraj. He realized that this made saliva—and therefore a cat's mouth--an unusually effective site for change. Hens exposed to Fel d1 produce their own antibodies, which survive in their eggs. The team coated LiveClear food with a powder form of these eggs; once in a cat's mouth, the chicken antibody binds to the Fel d1 in the cat's saliva, neutralizing it.

The results are partial: In a study with 105 cats, the level of active Fel d1 in their fur had dropped on average by 47 percent after ten weeks eating LiveClear. Cats that produced more Fel d1 at baseline had a more robust response, with a drop of up to 71 percent. A safety study found no effects on cats after six months on the diet. "Our goal was to ensure that whatever we do has no negative impact on the cat," Satyaraj said. Might a dogfood that minimizes dog allergens be on the way? "There is some early work," he said.

A Vaccine

This is a year when vaccines changed the lives of billions. Saiba's vaccine, HypoCat, delivers recombinant Fel d1 and the coat from a plant virus (the Cucumber mosaic virus) without any vital genetic information. The viral coat serves as a carrier. A cat would need shots once or twice a year to produce antibodies that neutralize Fel d1.

HypoCat works much like any vaccine, with the twist that the enemy is the cat's own protein. Is that safe? Saiba's team has followed 70 cats treated with the vaccine over two years and they remain healthy. Again the active Fel d1 doesn't disappear but diminishes. The team asked 10 people with cat allergies to report on their symptoms when they pet their vaccinated cats. Eight of them could pet their cat for nearly a half hour before their symptoms began, compared with an average of 17 minutes before the vaccine.

Jennings hopes to develop a HypoDog shot with a similar approach. However, the goal would be to target four or five proteins in one vaccine, and that increases the risk of hurting the dog. In the meantime, allergic dog-lovers considering an expensive breeder dog might think again: Independent research does not support the idea that any breed of dog produces less dander in the home. In fact, one well-designed study found that Spanish water dogs, Airedales, poodles and Labradoodles--breeds touted as hypo-allergenic--had significantly more of the most common allergen on their coat than an ordinary Lab and the control group.

Gene Editing

One day you might be able to bring your cat to the vet once a year for an injection that would modify specific tissues so they wouldn't produce Fel d1.

Nicole Brackett, a postdoctoral scientist at Viriginia-based Indoor Biotechnologies, which specializes in manufacturing biologics for allergy and asthma, most recently has used CRISPR to identify Fel d1 genetic sequences in cells from 50 domestic cats and 24 exotic ones. She learned that the sequences vary substantially from one cat to the next. This discovery, she says, backs up the observations that Fel d1 doesn't have a vital purpose.

The next step will be a CRISPR knockout of the relevant genes in cells from feline salivary glands, a prime source of Fel d1. Although the company is considering using CRISPR to edit the genes in a cat embryo and possibly produce a Fel d1-free cat, designer cats won't be its ultimate product. Instead, the company aims to produce injections that could treat any cat.

Reducing pet allergens at home could have a compound benefit, Indoor Biotechnologies founder Martin Chapman, an immunologist, notes: "When you dampen down the response to one allergen, you could also dampen it down to multiple allergens." As allergies become more common around the world, that's especially good news.