Antibody Testing Alone is Not the Key to Re-Opening Society

Immunity tests have too many unknowns right now to make them very useful in determining protective antibody status.

[Editor's Note: We asked experts from different specialties to weigh in on a timely Big Question: "How should immunity testing play a role in re-opening society?" Below, a virologist offers her perspective.]

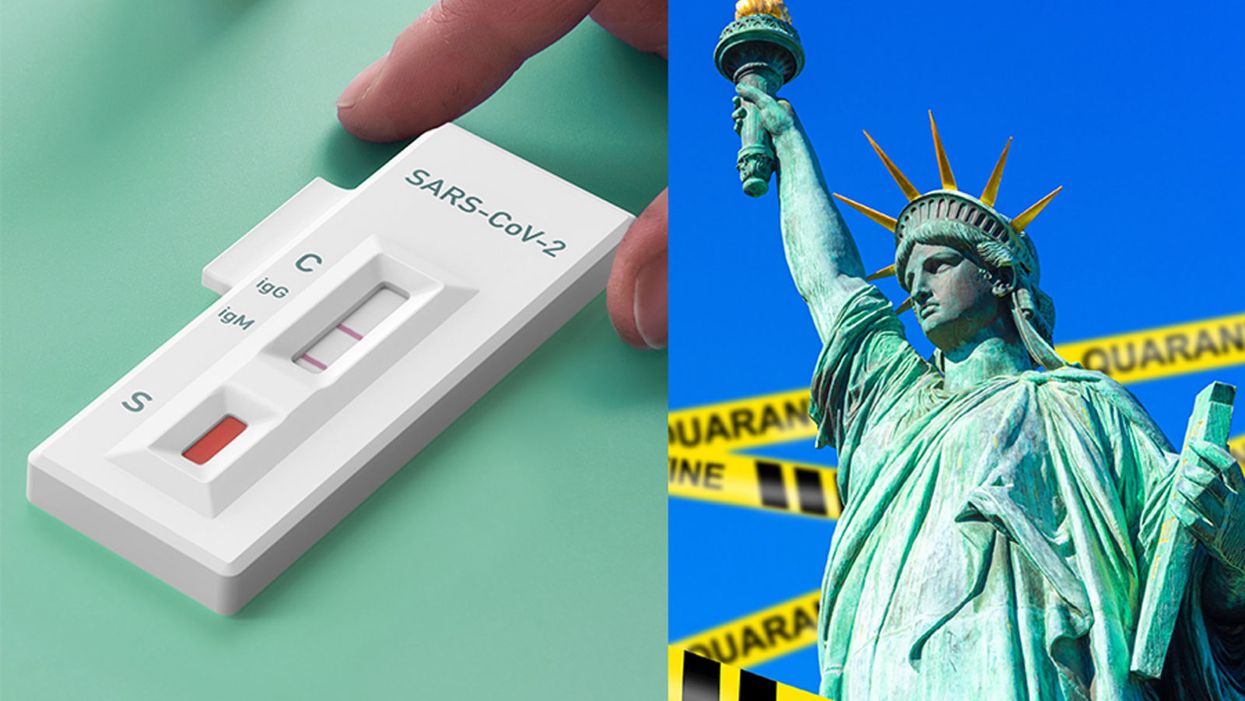

With the advent of serology testing and increased emphasis on "re-opening" America, public health officials have begun considering whether or not people who have recovered from COVID-19 can safely re-enter the workplace.

"Immunity certificates cannot certify what is not known."

Conventional wisdom holds that people who have developed antibodies in response to infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, are likely to be immune to reinfection.

For most acute viral infections, this is generally true. However, SARS-CoV-2 is a new pathogen, and there are currently many unanswered questions about immunity. Can recovered patients be reinfected or transmit the virus? Does symptom severity determine how protective responses will be after recovery? How long will protection last? Understanding these basic features is essential to phased re-opening of the government and economy for people who have recovered from COVID-19.

One mechanism that has been considered is issuing "immunity certificates" to individuals with antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. These certificates would verify that individuals have already recovered from COVID-19, and thus have antibodies in their blood that will protect them against reinfection, enabling them to safely return to work and participate in society. Although this sounds reasonable in theory, there are many practical reasons why this is not a wise policy decision to ease off restrictive stay-home orders and distancing practices.

Too Many Scientific Unknowns

Serology tests measure antibodies in the serum—the liquid component of blood, which is where the antibodies are located. In this case, serology tests measure antibodies that specifically bind to SARS-CoV-2 virus particles. Usually when a person is infected with a virus, they develop antibodies that can "recognize" that virus, so the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies indicates that a person has been previously exposed to the virus. Broad serology testing is critical to knowing how many people have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, since testing capacity for the virus itself has been so low.

Tests for the virus measure amounts of SARS-CoV-2 RNA—the virus's genetic material—directly, and thus will not detect the virus once a person has recovered. Thus, the majority of people who were not severely ill and did not require hospitalization, or did not have direct contact with a confirmed case, will not test positive for the virus weeks after they have recovered and can only determine if they had COVID-19 by testing for antibodies.

In most cases, for most pathogens, antibodies are also neutralizing, meaning they bind to the virus and render it incapable of infecting cells, and this protects against future infections. Immunity certificates are based on the assumption that people with antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2 will be protected against reinfection. The problem is that we've only known that SARS-CoV-2 existed for a little over four months. Although studies so far indicate that most (but not all) patients with confirmed COVID-19 cases develop antibodies, we don't know the extent to which antibodies are protective against reinfection, or how long that protection will last. Immunity certificates cannot certify what is not known.

The limited data so far is encouraging with regard to protective immunity. Most of the patient sera tested for antibodies show reasonable titers of IgG, the type of antibodies most likely to be neutralizing. Furthermore, studies have shown that these IgG antibodies are capable of neutralizing surrogate viruses as well as infectious SARS-CoV-2 in laboratory tests. In addition, rhesus monkeys that were experimentally infected with SARS-CoV-2 and allowed to recover were protected from reinfection after a subsequent experimental challenge. These data tentatively suggest that most people are likely to develop neutralizing IgG, and protective immunity, after being infected by SARS-CoV-2.

However, not all COVID-19 patients do produce high levels of antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2. A small number of patients in one study had no detectable neutralizing IgG. There have also been reports of patients in South Korea testing PCR positive after a prior negative test, indicating reinfection or reactivation. These cases may be explained by the sensitivity of the PCR test, and no data have been produced to indicate that these cases are genuine reinfection or recurrence of viral infection.

Complicating matters further, not all serology tests measure antibody titers. Some rapid serology tests are designed to be binary—the test can either detect antibodies or not, but does not give information about the amount of antibodies circulating. Based on our current knowledge, we cannot be certain that merely having any level of detectable antibodies alone guarantees protection from reinfection, or from a subclinical reinfection that might not cause a second case of COVID-19, but could still result in transmission to others. These unknowns remain problematic even with tests that accurately detect the presence of antibodies—which is not a given today, as many of the newly available tests are reportedly unreliable.

A Logistical and Ethical Quagmire

While most people are eager to cast off the isolation of physical distancing and resume their normal lives, mere desire to return to normality is not an indicator of whether those antibodies actually work, and no certificate can confer immune protection. Furthermore, immunity certificates could lead to some complicated logistical and ethical issues. If antibodies do not guarantee protective immunity, certifying that they do could give antibody-positive people a false sense of security, causing them to relax infection control practices such as distancing and hand hygiene.

"We should not, however, place our faith in assumptions and make return to normality contingent on an arbitrary and uninformative piece of paper."

Certificates could be forged, putting susceptible people at higher exposure risk. It's not clear who would issue them, what they would entitle the bearer to do or not do, or how certification would be verified or enforced. There are many ways in which such certificates could be used as a pretext to discriminate against people based on health status, in addition to disability, race, and socioeconomic status. Tracking people based on immune status raises further concerns about privacy and civil rights.

Rather than issuing documents confirming immune status, we should instead "re-open" society cautiously, with widespread virus and serology testing to accurately identify and isolate infected cases rapidly, with immediate contact tracing to safely quarantine and monitor those at exposure risk. Broad serosurveillance must be coupled with functional assays for neutralization activity to begin assessing how protective antibodies might actually be against SARS-CoV-2 infection. To understand how long immunity lasts, we should study antibodies, as well as the functional capabilities of other components of the larger immune system, such as T cells, in recovered COVID-19 patients over time.

We should not, however, place our faith in assumptions and make return to normality contingent on an arbitrary and uninformative piece of paper. Re-opening society, the government, and the economy depends not only on accurately determining how many people have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, but on a deeper understanding of how those antibodies work to provide protection.

Scientists make progress with growing organs for transplants

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have laid the foundations for growing synthetic embryos that could develop a beating heart, gut and brain.

Story by Big Think

For over a century, scientists have dreamed of growing human organs sans humans. This technology could put an end to the scarcity of organs for transplants. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The capability to grow fully functional organs would revolutionize research. For example, scientists could observe mysterious biological processes, such as how human cells and organs develop a disease and respond (or fail to respond) to medication without involving human subjects.

Recently, a team of researchers from the University of Cambridge has laid the foundations not just for growing functional organs but functional synthetic embryos capable of developing a beating heart, gut, and brain. Their report was published in Nature.

The organoid revolution

In 1981, scientists discovered how to keep stem cells alive. This was a significant breakthrough, as stem cells have notoriously rigorous demands. Nevertheless, stem cells remained a relatively niche research area, mainly because scientists didn’t know how to convince the cells to turn into other cells.

Then, in 1987, scientists embedded isolated stem cells in a gelatinous protein mixture called Matrigel, which simulated the three-dimensional environment of animal tissue. The cells thrived, but they also did something remarkable: they created breast tissue capable of producing milk proteins. This was the first organoid — a clump of cells that behave and function like a real organ. The organoid revolution had begun, and it all started with a boob in Jello.

For the next 20 years, it was rare to find a scientist who identified as an “organoid researcher,” but there were many “stem cell researchers” who wanted to figure out how to turn stem cells into other cells. Eventually, they discovered the signals (called growth factors) that stem cells require to differentiate into other types of cells.

For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells.

By the end of the 2000s, researchers began combining stem cells, Matrigel, and the newly characterized growth factors to create dozens of organoids, from liver organoids capable of producing the bile salts necessary for digesting fat to brain organoids with components that resemble eyes, the spinal cord, and arguably, the beginnings of sentience.

Synthetic embryos

Organoids possess an intrinsic flaw: they are organ-like. They share some characteristics with real organs, making them powerful tools for research. However, no one has found a way to create an organoid with all the characteristics and functions of a real organ. But Magdalena Żernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist, might have set the foundation for that discovery.

Żernicka-Goetz hypothesized that organoids fail to develop into fully functional organs because organs develop as a collective. Organoid research often uses embryonic stem cells, which are the cells from which the developing organism is created. However, there are two other types of stem cells in an early embryo: stem cells that become the placenta and those that become the yolk sac (where the embryo grows and gets its nutrients in early development). For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells. In other words, Żernicka-Goetz suspected the best way to grow a functional organoid was to produce a synthetic embryoid.

As described in the aforementioned Nature paper, Żernicka-Goetz and her team mimicked the embryonic environment by mixing these three types of stem cells from mice. Amazingly, the stem cells self-organized into structures and progressed through the successive developmental stages until they had beating hearts and the foundations of the brain.

“Our mouse embryo model not only develops a brain, but also a beating heart [and] all the components that go on to make up the body,” said Żernicka-Goetz. “It’s just unbelievable that we’ve got this far. This has been the dream of our community for years and major focus of our work for a decade and finally we’ve done it.”

If the methods developed by Żernicka-Goetz’s team are successful with human stem cells, scientists someday could use them to guide the development of synthetic organs for patients awaiting transplants. It also opens the door to studying how embryos develop during pregnancy.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

Scientists find enzymes in nature that could replace toxic chemicals

Basecamp Research is using portable labs like this one to gather samples from ecosystems around the world.

Some 900 miles off the coast of Portugal, nine major islands rise from the mid-Atlantic. Verdant and volcanic, the Azores archipelago hosts a wealth of biodiversity that keeps field research scientist, Marlon Clark, returning for more. “You’ve got this really interesting biogeography out there,” says Clark. “There’s real separation between the continents, but there’s this inter-island dispersal of plants and seeds and animals.”

It’s a visual paradise by any standard, but on a microscopic level, there’s even more to see. The Azores’ nutrient-rich volcanic rock — and its network of lagoons, cave systems, and thermal springs — is home to a vast array of microorganisms found in a variety of microclimates with different elevations and temperatures.

Clark works for Basecamp Research, a biotech company headquartered in London, and his job is to collect samples from ecosystems around the world. By extracting DNA from soil, water, plants, microbes and other organisms, Basecamp is building an extensive database of the Earth’s proteins. While DNA itself isn’t a protein, the information stored in DNA is used to create proteins, so extracting, sequencing, and annotating DNA allows for the discovery of unique protein sequences.

Using what they’re finding in the middle of the Atlantic and beyond, Basecamp’s detailed database is constantly growing. The outputs could be essential for cleaning up the damage done by toxic chemicals and finding alternatives to these chemicals.

Catalysts for change

Proteins provide structure and function in all living organisms. Some of these functional proteins are enzymes, which quite literally make things happen.

“Industrial chemistry is heavily polluting, especially the chemistry done in pharmaceutical drug development. Biocatalysis is providing advantages, both to make more complex drugs and to be more sustainable, reducing the pollution and toxicity of conventional chemistry," says Ahir Pushpanath, who heads partnerships for Basecamp.

“Enzymes are perfectly evolved catalysts,” says Ahir Pushpanath, a partnerships lead at Basecamp. ”Enzymes are essentially just a polymer, and polymers are made up of amino acids, which are nature’s building blocks.” He suggests thinking about it like Legos — if you have a bunch of Lego pieces and use them to build a structure that performs a function, “that’s basically how an enzyme works. In nature, these monuments have evolved to do life’s chemistry. If we didn’t have enzymes, we wouldn’t be alive.”

In our own bodies, enzymes catalyze everything from vision to digesting food to regrowing muscles, and these same types of enzymes are necessary in the pharmaceutical, agrochemical and fine chemical industries. But industrial conditions differ from those inside our bodies. So, when scientists need certain chemical reactions to create a particular product or substance, they make their own catalysts in their labs — generally through the use of petroleum and heavy metals.

These petrochemicals are effective and cost-efficient, but they’re wasteful and often hazardous. With growing concerns around sustainability and long-term public health, it's essential to find alternative solutions to toxic chemicals. “Industrial chemistry is heavily polluting, especially the chemistry done in pharmaceutical drug development,” Pushpanath says.

Basecamp is trying to replace lab-created catalysts with enzymes found in the wild. This concept is called biocatalysis, and in theory, all scientists have to do is find the right enzymes for their specific need. Yet, historically, researchers have struggled to find enzymes to replace petrochemicals. When they can’t identify a suitable match, they turn to what Pushpanath describes as “long, iterative, resource-intensive, directed evolution” in the laboratory to coax a protein into industrial adaptation. But the latest scientific advances have enabled these discoveries in nature instead.

Marlon Clark, a research scientist at Basecamp Research, looks for novel biochemistries in the Azores.

Glen Gowers

Enzyme hunters

Whether it’s Clark and a colleague setting off on an expedition, or a local, on-the-ground partner gathering and processing samples, there’s a lot to be learned from each collection. “Microbial genomes contain complete sets of information that define an organism — much like how letters are a code allowing us to form words, sentences, pages, and books that contain complex but digestible knowledge,” Clark says. He thinks of the environmental samples as biological libraries, filled with thousands of species, strains, and sequence variants. “It’s our job to glean genetic information from these samples.”

“We can actually dream up new proteins using generative AI," Pushpanath says.

Basecamp researchers manage this feat by sequencing the DNA and then assembling the information into a comprehensible structure. “We’re building the ‘stories’ of the biota,” Clark says. The more varied the samples, the more valuable insights his team gains into the characteristics of different organisms and their interactions with the environment. Sequencing allows scientists to examine the order of nucleotides — the organic molecules that form DNA — to identify genetic makeups and find changes within genomes. The process used to be too expensive, but the cost of sequencing has dropped from $10,000 a decade ago to as low as $100. Notably, biocatalysis isn’t a new concept — there have been waves of interest in using natural enzymes in catalysis for over a century, Pushpanath says. “But the technology just wasn’t there to make it cost effective,” he explains. “Sequencing has been the biggest boon.”

AI is probably the second biggest boon.

“We can actually dream up new proteins using generative AI,” Pushpanath says, which means that biocataylsis now has real potential to scale.

Glen Gowers, the co-founder of Basecamp, compares the company’s AI approach to that of social networks and streaming services. Consider how these platforms suggest connecting with the friends of your friends, or how watching one comedy film from the 1990s leads to a suggestion of three more.

“They’re thinking about data as networks of relationships as opposed to lists of items,” says Gowers. “By doing the same, we’re able to link the metadata of the proteins — by their relationships to each other, the environments in which they’re found, the way those proteins might look similar in sequence and structure, their surrounding genome context — really, this just comes down to creating a searchable network of proteins.”

On an Azores island, this volcanic opening may harbor organisms that can help scientists identify enzymes for biocatalysis to replace toxic chemicals.

Emma Bolton

Uwe Bornscheuer, professor at the Institute of Biochemistry at the University of Greifswald, and co-founder of Enzymicals, another biocatalysis company, says that the development of machine learning is a critical component of this work. “It’s a very hot topic, because the challenge in protein engineering is to predict which mutation at which position in the protein will make an enzyme suitable for certain applications,” Bornscheuer explains. These predictions are difficult for humans to make at all, let alone quickly. “It is clear that machine learning is a key technology.”

Benefiting from nature’s bounty

Biodiversity commonly refers to plants and animals, but the term extends to all life, including microbial life, and some regions of the world are more biodiverse than others. Building relationships with global partners is another key element to Basecamp’s success. Doing so in accordance with the access and benefit sharing principles set forth by the Nagoya Protocol — an international agreement that seeks to ensure the benefits of using genetic resources are distributed in a fair and equitable way — is part of the company's ethos. “There's a lot of potential for us, and there’s a lot of potential for our partners to have exactly the same impact in building and discovering commercially relevant proteins and biochemistries from nature,” Clark says.

Bornscheuer points out that Basecamp is not the first company of its kind. A former San Diego company called Diversa went public in 2000 with similar work. “At that time, the Nagoya Protocol was not around, but Diversa also wanted to ensure that if a certain enzyme or microorganism from Costa Rica, for example, were used in an industrial process, then people in Costa Rica would somehow profit from this.”

An eventual merger turned Diversa into Verenium Corporation, which is now a part of the chemical producer BASF, but it laid important groundwork for modern companies like Basecamp to continue to scale with today’s technologies.

“To collect natural diversity is the key to identifying new catalysts for use in new applications,” Bornscheuer says. “Natural diversity is immense, and over the past 20 years we have gained the advantages that sequencing is no longer a cost or time factor.”

This has allowed Basecamp to rapidly grow its database, outperforming Universal Protein Resource or UniProt, which is the public repository of protein sequences most commonly used by researchers. Basecamp’s database is three times larger, totaling about 900 million sequences. (UniProt isn’t compliant with the Nagoya Protocol, because, as a public database, it doesn’t provide traceability of protein sequences. Some scientists, however, argue that Nagoya compliance hinders progress.)

“Eventually, this work will reduce chemical processes. We’ll have cleaner processes, more sustainable processes," says Uwe Bornscheuer, a professor at the University of Greifswald.

With so much information available, Basecamp’s AI has been trained on “the true dictionary of protein sequence life,” Pushpanath says, which makes it possible to design sequences for particular applications. “Through deep learning approaches, we’re able to find protein sequences directly from our database, without the need for further laboratory-directed evolution.”

Recently, a major chemical company was searching for a specific transaminase — an enzyme that catalyzes a transfer of amino groups. “They had already spent a year-and-a-half and nearly two million dollars to evolve a public-database enzyme, and still had not reached their goal,” Pushpanath says. “We used our AI approaches on our novel database to yield 10 candidates within a week, which, when validated by the client, achieved the desired target even better than their best-evolved candidate.”

Basecamp’s other huge potential is in bioremediation, where natural enzymes can help to undo the damage caused by toxic chemicals. “Biocatalysis impacts both sides,” says Gowers. “It reduces the usage of chemicals to make products, and at the same time, where contamination sites do exist from chemical spills, enzymes are also there to kind of mop those up.”

So far, Basecamp's round-the-world sampling has covered 50 percent of the 14 major biomes, or regions of the planet that can be distinguished by their flora, fauna, and climate, as defined by the World Wildlife Fund. The other half remains to be catalogued — a key milestone for understanding our planet’s protein diversity, Pushpanath notes.

There’s still a long road ahead to fully replace petrochemicals with natural enzymes, but biocatalysis is on an upward trajectory. "Eventually, this work will reduce chemical processes,” Bornscheuer says. “We’ll have cleaner processes, more sustainable processes.”