Bivalent Boosters for Young Children Are Elusive. The Search Is On for Ways to Improve Access.

Theo, an 18-month-old in rural Nebraska, walks with his father in their backyard. For many toddlers, the barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccines are many, such as few locations giving vaccines to very young children.

It’s Theo’s* first time in the snow. Wide-eyed, he totters outside holding his father’s hand. Sarah Holmes feels great joy in watching her 18-month-old son experience the world, “His genuine wonder and excitement gives me so much hope.”

In the summer of 2021, two months after Theo was born, Holmes, a behavioral health provider in Nebraska lost her grandparents to COVID-19. Both were vaccinated and thought they could unmask without any risk. “My grandfather was a veteran, and really trusted the government and faith leaders saying that COVID-19 wasn’t a threat anymore,” she says.” The state of emergency in Louisiana had ended and that was the message from the people they respected. “That is what killed them.”

The current official public health messaging is that regardless of what variant is circulating, the best way to be protected is to get vaccinated. These warnings no longer mention masking, or any of the other Swiss-cheese layers of mitigation that were prevalent in the early days of this ongoing pandemic.

The problem with the prevailing, vaccine centered strategy is that if you are a parent with children under five, barriers to access are real. In many cases, meaningful tools and changes that would address these obstacles are lacking, such as offering vaccines at more locations, mandating masks at these sites, and providing paid leave time to get the shots.

Children are at risk

Data presented at the most recent FDA advisory panel on COVID-19 vaccines showed that in the last year infants under six months had the third highest rate of hospitalization. “From the beginning, the message has been that kids don’t get COVID, and then the message was, well kids get COVID, but it’s not serious,” says Elias Kass, a pediatrician in Seattle. “Then they waited so long on the initial vaccines that by the time kids could get vaccinated, the majority of them had been infected.”

A closer look at the data from the CDC also reveals that from January 2022 to January 2023 children aged 6 to 23 months were more likely to be hospitalized than all other vaccine eligible pediatric age groups.

“We sort of forced an entire generation of kids to be infected with a novel virus and just don't give a shit, like nobody cares about kids,” Kass says. In some cases, COVID has wreaked havoc with the immune systems of very young children at his practice, making them vulnerable to other illnesses, he said. “And now we have kids that have had COVID two or three times, and we don’t know what is going to happen to them.”

Jumping through hurdles

Children under five were the last group to have an emergency use authorization (EUA) granted for the COVID-19 vaccine, a year and a half after adult vaccine approval. In June 2022, 30,000 sites were initially available for children across the country. Six months later, when boosters became available, there were only 5,000.

Currently, only 3.8% of children under two have completed a primary series, according to the CDC. An even more abysmal 0.2% under two have gotten a booster.

Ariadne Labs, a health center affiliated with Harvard, is trying to understand why these gaps exist. In conjunction with Boston Children’s Hospital, they have created a vaccine equity planner that maps the locations of vaccine deserts based on factors such as social vulnerability indexes and transportation access.

“People are having to travel farther because the sites are just few and far between,” says Benjy Renton, a research assistant at Ariadne.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. When the boosters first came out she expected her toddler could get it close to home, but her husband had to drive Charlee four hours roundtrip.

This experience hasn’t been uncommon, especially in rural parts of the U.S. If parents wanted vaccines for their young children shortly after approval, they faced the prospect of loading babies and toddlers, famous for their calm demeanor, into cars for lengthy rides. The situation continues today. Mrs. Smith*, a grant writer and non-profit advisor who lives in Idaho, is still unable to get her child the bivalent booster because a two-hour one-way drive in winter weather isn’t possible.

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited.

Protect Their Future (PTF), a grassroots organization focusing on advocacy for the health care of children, hears from parents several times a week who are having trouble finding vaccines. The vaccine rollout “has been a total mess,” says Tamara Lea Spira, co-founder of PTF “It’s been very hard for people to access vaccines for children, particularly those under three.”

Seventeen states have passed laws that give pharmacists authority to vaccinate as young as six months. Under federal law, the minimum age in other states is three. Even in the states that allow vaccination of toddlers, each pharmacy chain varies. Some require prescriptions.

It takes time to make phone calls to confirm availability and book appointments online. “So it means that the parents who are getting their children vaccinated are those who are even more motivated and with the time and the resources to understand whether and how their kids can get vaccinated,” says Tiffany Green, an associate professor in population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Green adds, “And then we have the contraction of vaccine availability in terms of sites…who is most likely to be affected? It's the usual suspects, children of color, disabled children, low-income children.”

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited. In Bibb County, Ala., vaccinations take place only on Wednesdays from 1:45 to 3:00 pm.

“People who are focused on putting food on the table or stressed about having enough money to pay rent aren't going to prioritize getting vaccinated that day,” says Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy and management at Boston University. She created the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy Database, which tracks state health and economic policies related to the pandemic.

Most states in the U.S. lack paid sick leave policies, and the average paid sick days with private employers is about one week. Green says, “I think COVID should have been a wake-up call that this is necessary.”

Maskless waiting rooms

For her son, Holmes spent hours making phone calls but could uncover no clear answers. No one could estimate an arrival date for the booster. “It disappoints me greatly that the process for locating COVID-19 vaccinations for young children requires so much legwork in terms of time and resources,” she says.

In January, she found a pharmacy 30 minutes away that could vaccinate Theo. With her son being too young to mask, she waited in the car with him as long as possible to avoid a busy, maskless waiting room.

Kids under two, such as Theo, are advised not to wear masks, which make it too hard for them to breathe. With masking policies a rarity these days, waiting rooms for vaccines present another barrier to access. Even in healthcare settings, current CDC guidance only requires masking during high transmission or when treating COVID positive patients directly.

“This is a group that is really left behind,” says Raifman. “They cannot wear masks themselves. They really depend on others around them wearing masks. There's not even one train car they can go on if their parents need to take public transportation… and not risk COVID transmission.”

Yet another challenge is presented for those who don’t speak English or Spanish. According to Translators without Borders, 65 million people in America speak a language other than English. Most state departments of health have a COVID-19 web page that redirects to the federal vaccines.gov in English, with an option to translate to Spanish only.

The main avenue for accessing information on vaccines relies on an internet connection, but 22 percent of rural Americans lack broadband access. “People who lack digital access, or don’t speak English…or know how to navigate or work with computers are unable to use that service and then don’t have access to the vaccines because they just don’t know how to get to them,” Jirmanus, an affiliate of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard and a member of The People’s CDC explains. She sees this issue frequently when working with immigrant communities in Massachusetts. “You really have to meet people where they’re at, and that means physically where they’re at.”

Equitable solutions

Grassroots and advocacy organizations like PTF have been filling a lot of the holes left by spotty federal policy. “In many ways this collective care has been as important as our gains to access the vaccine itself,” says Spira, the PTF co-founder.

PTF facilitates peer-to-peer networks of parents that offer support to each other. At least one parent in the group has crowdsourced information on locations that are providing vaccines for the very young and created a spreadsheet displaying vaccine locations. “It is incredible to me still that this vacuum of information and support exists, and it took a totally grassroots and volunteer effort of parents and physicians to try and respond to this need.” says Spira.

Kass, who is also affiliated with PTF, has been vaccinating any child who comes to his independent practice, regardless of whether they’re one of his patients or have insurance. “I think putting everything on retail pharmacies is not appropriate. By the time the kids' vaccines were released, all of our mass vaccination sites had been taken down.” A big way to help parents and pediatricians would be to allow mixing and matching. Any child who has had the full Pfizer series has had to forgo a bivalent booster.

“I think getting those first two or three doses into kids should still be a priority, and I don’t want to lose sight of all that,” states Renton, the researcher at Ariadne Labs. Through the vaccine equity planner, he has been trying to see if there are places where mobile clinics can go to improve access. Renton continues to work with local and state planners to aid in vaccine planning. “I think any way we can make that process a lot easier…will go a long way into building vaccine confidence and getting people vaccinated,” Renton says.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. Her husband had to drive four hours roundtrip to get the boosters for Charlee.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch

Other changes need to come from the CDC. Even though the CDC “has this historic reputation and a mission of valuing equity and promoting health,” Jirmanus says, “they’re really failing. The emphasis on personal responsibility is leaving a lot of people behind.” She believes another avenue for more equitable access is creating legislation for upgraded ventilation in indoor public spaces.

Given the gaps in state policies, federal leadership matters, Raifman says. With the FDA leaning toward a yearly COVID vaccine, an equity lens from the CDC will be even more critical. “We can have data driven approaches to using evidence based policies like mask policies, when and where they're most important,” she says. Raifman wants to see a sustainable system of vaccine delivery across the country complemented with a surge preparedness plan.

With the public health emergency ending and vaccines going to the private market sometime in 2023, it seems unlikely that vaccine access is going to improve. Now more than ever, ”We need to be able to extend to people the choice of not being infected with COVID,” Jirmanus says.

*Some names were changed for privacy reasons.

At the “Apple Store of Doctor’s Offices,” Preventive Care Is High Tech. Is it Worth $150 a Month?

A patient getting examined at health startup Forward.

What if going to the doctor's office could be … nice?

If you didn't have to wait for your appointment, but were ushered right in; if your medical data was all collated and easily searchable on an iPhone app; if a remote scribe took notes while you spoke with your doctor so you could make eye contact with them; if your doctor didn't seem horribly rushed.

Would you go to the doctor to get help staying healthy, rather than just to stop being sick?

Would that change the way you thought about your health? Would you go to the doctor to get help staying healthy, rather than just to stop being sick? And would that, in the long run, be much better for you?

Those are the animating questions for Forward, a healthcare startup devoted to preventive care. Led by founder Adrian Aoun, formerly of Google/Sidewalk labs, Forward opened its first office in San Francisco in 2016 and has since expanded to Los Angeles, Orange County, New York, and Washington, D.C., with a San Diego location opening soon.

It's been described as the "Apple Store of doctor's offices," which in some ways is a reaction to Forward's vibe: Patients have described the offices as having blonde wood, minimalist design, sparkling water on tap — and lots of high-tech gadgets, like the full-body scanner that replaces the standard scale and stethoscope.

The interior of a Forward office.

(Courtesy Forward)

The more crucial difference, though, is its model of care. Forward doesn't take insurance. Instead, patients, or "members," pay a flat $149 per month, along the lines of a subscription service like Netflix or a gym membership. That fee covers visits, messaging with medical staff through the Forward app, the use of a wearable (like a Fitbit or a sleep tracker) if the physician recommends it, plus any bloodwork or diagnostic tests run in the on-site labs. (The company declined to disclose how many people have signed up for memberships.)

Predictability is Forward's other significant, distinguishing feature: No surprise co-pays, or extra charges showing up on a billing statement months later. Everything is wrapped up in the $149 membership fee, unless the physician recommends visiting an outside specialist.

That caveat isn't a small one. It's important to note that Forward is in no way meant to replace standard health insurance. The service is strictly focused on preventive care, so it wouldn't be much use in case of an emergency; it's meant to help people, as far as is possible, avoid that emergency at all.

Ani Okkasian's family recently went through such an emergency. Her 62-year-old father, an active and seemingly healthy man living with diabetes, had been feeling unwell for a while, but struggled to receive constructive follow-up or tests from his doctor. It finally emerged that his liver was severely damaged, and he suffered a stroke — the risk of which can be elevated by liver disease. He seemed to deteriorate completely within mere weeks, Okkasian said, and in January he passed away.

"He was someone who'd go to the doctor regularly and listen to what they said and follow it," Okkasian said. "I shouldn't have had to bury my father at 62. I still believe to my core that his death could have been avoided if the primary care was adequate."

"I could tell that the people who designed [Forward] had lost someone to the legacy system; it was so streamlined and so much clearer."

Okkasian began researching, looking for a better alternative, and discovered Forward. Founder Aoun lost his grandfather to a heart attack; his brother's heart attack at age 31 was the impetus to start Forward.

"I could tell that that was the genesis," Okkasian said. "Having just lost someone, and having had to deal with different aspects of the healthcare industry — how complicated and convoluted that all is — I could tell that the people who designed [Forward] had lost someone to the legacy system; it was so streamlined and so much clearer."

So Who Is Forward For?

The Affordable Care Act mandates that evidence-based preventive care must be covered by insurers without any cost to the patient. Today, 30 million Americans are still living without health insurance; but for most of the population, cost shouldn't prevent access to standard, preventive care, says Benjamin Sommers, a physician and professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health who has studied the effect of the ACA on preventive care access.

For Okkasian and her family, it wasn't a lack of access to primary care that was at issue; it was the quality of that primary care. In 2019, that's probably true for a lot of people.

"How come all other industries have been disturbed except the medical industry?" Okkasian asked. "It's disturbing the most people. We're so advanced in so many ways, but when it comes to the healthcare system, we're not prioritizing the wellness of a person."

Is Forward the answer? Well, probably not for everyone. Its office are only in a handful of cities, and there are limits to how scalable it would be; it's unavoidable that the $149 per month charge restricts access for a lot of people. Those who have insurance through their employer might have a flexible spending account (FSA) that would cover some or all of the membership fee, and Forward has said that 15 percent of their early members came from underserved communities and were offered free plans; but for many others, that's just an unworkable extra cost.

Sommers also sounded a dubious note about a maximalist attitude toward data collection.

"Even though some patients may think that 'more is always better' — more testing, more screening, etc. — this isn't true," he said. "Some types of cancer screening, ovarian cancer screening for instance, are actually harmful or of no benefit, because studies have shown that they don't improve survival or health outcomes, but can lead to unnecessary testing, pain, false positives, anxiety, and other side effects.

"It's really great for people who are in good health, looking to make it better."

"I'm generally skeptical of efforts to charge people more to get 'extra testing' that isn't currently supported by the medical evidence," he added.

But relatively healthy people who want to take a more active approach to their health — or people who have frequent testing needs, like those using the HIV-prevention drug PrEP, and want to avoid co-pays — might benefit from the on-demand, low-friction experience that Forward offers.

"It's really great for people who are in good health, looking to make it better," Okkasian said. "Your experience is simplified to a point where you feel empowered, not scared."

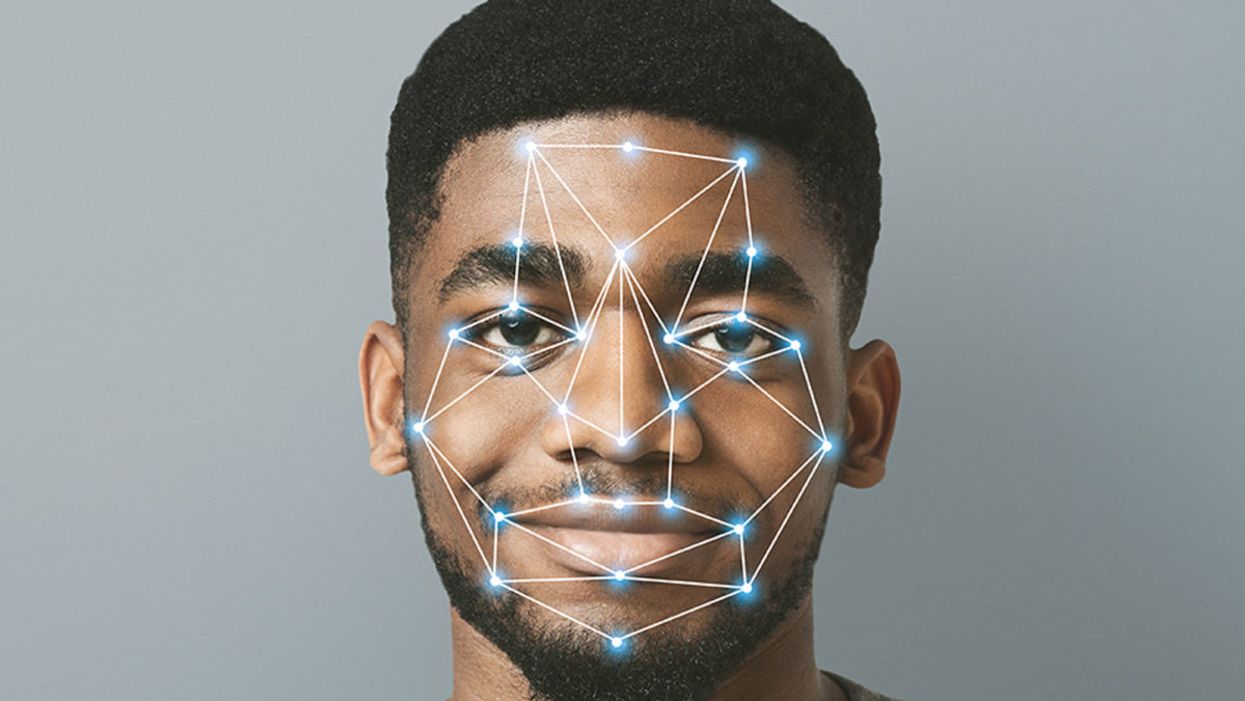

Facial Recognition Can Reduce Racial Profiling and False Arrests

The use of face recognition technology is expanding exponentially right now.

[Editor's Note: This essay is in response to our current Big Question, which we posed to experts with different perspectives: "Do you think the use of facial recognition technology by the police or government should be banned? If so, why? If not, what limits, if any, should be placed on its use?"]

Opposing facial recognition technology has become an article of faith for civil libertarians. Many who supported the bans in cities like San Francisco and Oakland have declared the technology to be inherently racist and abusive.

The greatest danger would be to categorically oppose this technology and pretend that it will simply go away.

I have spent my career as a criminal defense attorney and a civil libertarian -- and I do not fear it. Indeed, I see it as positive so long as it is appropriately regulated and controlled.

We are living in the beginning of a biometric age, where technology uses our physical or biological characteristics for a variety of products and services. It holds great promises as well as great risks. The greatest danger, however, would be to categorically oppose this technology and pretend that it will simply go away.

This is an age driven as much by consumer as it is government demand. Living in denial may be emotionally appealing, but it will only hasten the creation of post-privacy world. If we do not address this emerging technology, movements in public will increasingly result in instant recognition and even tracking. It is the type of fish-bowl society that strips away any expectation of privacy in our interactions and associations.

The biometrics field is expanding exponentially, largely due to the popularity of consumer products using facial recognition technology (FRT) -- from the iPhone program to shopping ones that recognize customers.

But the privacy community is losing this battle because it is using the privacy rationales and doctrines forged in the earlier electronic surveillance periods. Just as generals are often accused of planning to fight the last war, civil libertarians can sometimes cling to past models despite their decreasing relevance in the current world.

I see FRT as having positive implications that are worth pursuing. When properly used, biometrics can actually enhance privacy interests and even reduce racial profiling by reducing false arrests and the warrantless "patdowns" allowed by the Supreme Court. Bans not only deny police a technology widely used by businesses, but return police to the highly flawed default of "eye balling" suspects -- a system with a considerably higher error rate than top FRT programs.

Officers are often wrong and stop a great number of suspects in the hopes of finding a wanted felon.

A study in Australia showed that passport officers who had taken photographs of subjects in ideal conditions nonetheless experienced high error rates when identifying them shortly afterward, including 14 percent false acceptance rates. Currently, officers stop suspects based on their memory from seeing a photograph days or weeks earlier. They are often wrong and stop a great number of suspects in the hopes of finding a wanted felon. The best FRT programs achieve an astonishing accuracy rate, though real-world implementation has challenges that must be addressed.

One legitimate concern raised in early studies showed higher error rates in recognitions for certain groups, particularly African American women. An MIT study finding that error rate prompted major improvements in the algorithms as well as training changes to greatly reduce the frequency of errors. The issue remains a concern, but there is nothing inherently racist in algorithms. These are a set of computer instructions that isolate and process with the parameters and conditions set by creators.

To be sure, there is room for improvement in some algorithms. Tests performed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reportedly showed only an 80 percent accuracy rate in comparing mug shots to pictures of members of Congress when using Amazon's "Rekognition" system. It recently showed the same 80 percent rate in doing the same comparison to members of the California legislators.

However, different algorithms are available with differing levels of performance. Moreover, these products can be set with a lower discrimination level. The fact is that the top algorithms tested by the National Institute of Standards and Technology showed that their accuracy rate is greater than 99 percent.

The greatest threat of biometric technologies is to democratic values.

Assuming a top-performing algorithm is used, the result could be highly beneficial for civil liberties as opposed to the alternative of "eye balling" suspects. Consider the Boston Bombing where police declared a "containment zone" and forced families into the street with their hands in the air.

The suspect, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, moved around Boston and was ultimately found outside the "containment zone" once authorities abandoned near martial law. He was caught on some surveillance systems but not identified. FRT can help law enforcement avoid time-consuming area searches and the questionable practice of forcing people out of their homes to physically examine them.

If we are to avoid a post-privacy world, we will have to redefine what we are trying to protect and reconceive how we hope to protect it. In my view, the greatest threat of biometric technologies is to democratic values. Authoritarian nations like China have made huge investments into FRT precisely because they know that the threat of recognition in public deters citizens from associating or interacting with protesters or dissidents. Recognition changes conduct. That chilling effect is what we have the worry about the most.

Conventional privacy doctrines do not offer much protection. The very concept of "public privacy" is treated as something of an oxymoron by courts. Public acts and associations are treated as lacking any reasonable expectation of privacy. In the same vein, the right to anonymity is not a strong avenue for protection. We are not living in an anonymous world anymore.

Consumers want products like FaceFind, which link their images with others across social media. They like "frictionless" transactions and authentications using faceprints. Despite the hyperbole in places like San Francisco, civil libertarians will not succeed in getting that cat to walk backwards.

The basis for biometric privacy protection should not be focused on anonymity, but rather obscurity. You will be increasingly subject to transparency-forcing technology, but we can legislatively mandate ways of obscuring that information. That is the objective of the Biometric Privacy Act that I have proposed in recent research. However, no such comprehensive legislation has passed through Congress.

The ability to spot fraudulent entries at airports or recognizing a felon in flight has obvious benefits for all citizens.

We also need to recognize that FRT has many beneficial uses. Biometric guns can reduce accidents and criminals' conduct. New authentications using FRT and other biometric programs could reduce identity theft.

And, yes, FRT could help protect against unnecessary police stops or false arrests. Finally, and not insignificantly, this technology could stop serious crimes, from terrorist attacks to the capturing of dangerous felons. The ability to spot fraudulent entries at airports or recognizing a felon in flight has obvious benefits for all citizens.

We can live and thrive in a biometric era. However, we will need to bring together civil libertarians with business and government experts if we are going to control this technology rather than have it control us.

[Editor's Note: Read the opposite perspective here.]