Black Participants Are Sorely Absent from Medical Research

Black participants are under-represented in clinical research.

After years of suffering from mysterious symptoms, my mother Janice Thomas finally found a doctor who correctly diagnosed her with two autoimmune diseases, Lupus and Sjogren's. Both diseases are more prevalent in the black population than in other races and are often misdiagnosed.

The National Institutes of Health has found that minorities make up less than 10 percent of trial participants.

Like many chronic health conditions, a lack of understanding persists about their causes, individual manifestations, and best treatment strategies.

On the search for relief from chronic pain, my mother started researching options and decided to participate in clinical trials as a way to gain much-needed insights. In return, she received discounted medical testing and has played an active role in finding answers for all.

"When my doctor told me I could get financial or medical benefits from participating in clinical trials for the same test I was already doing, I figured it would be an easy way to get some answers at little to no cost," she says.

As a person of color, her presence in clinical studies is rare. The National Institutes of Health has found that minorities make up less than 10 percent of trial participants.

Without trial participation that is reflective of the general population, pharmaceutical companies and medical professionals are left guessing how various drugs work across racial lines. For example, albuterol, a widely used asthma treatment, was found to have decreased effectiveness for black American and Puerto Rican children. Many high mortality conditions, like cancer, also show different outcomes based on race.

Over the last decade, the pervasive lack of representation has left communities of color demanding higher levels of involvement in the research process. However, no consensus yet exists on how best to achieve this.

But experts suggest that before we can improve black participation in medical studies, key misconceptions must be addressed, such as the false assumption that such patients are unwilling to participate because they distrust scientists.

Jill A. Fisher, a professor in the Center for Bioethics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, learned in one study that mistrust wasn't the main barrier for black Americans. "There is a lot of evidence that researchers' recruitment of black Americans is generally poorly done, with many black patients simply not asked," Fisher says. "Moreover, the underrepresentation of black Americans is primarily true for efficacy trials - those testing whether an investigational drug might therapeutically benefit patients with specific illnesses."

Without increased minority participation, research will not accurately reflect the diversity of the general population.

Dr. Joyce Balls-Berry, a psychiatric epidemiologist and health educator, agrees that black Americans are often overlooked in the process. One study she conducted found that "enrollment of minorities in clinical trials meant using a variety of culturally appropriate strategies to engage participants," she explained.

To overcome this hurdle, The National Black Church Initiative (NBCI), a faith-based organization made up of 34,000 churches and over 15.7 million African Americans, last year urged the Food and Drug Administration to mandate diversity in all clinical trials before approving a drug or device. However, the FDA declined to implement the mandate, declaring that they don't have the authority to regulate diversity in clinical trials.

"African Americans have not been successfully incorporated into the advancement of medicine and research technologies as legitimate and natural born citizens of this country," admonishes NBCI's president Rev. Anthony Evans.

His words conjure a reminder of the medical system's insidious history for people of color. The most infamous incident is the Tuskegee syphilis scandal, in which white government doctors perpetrated harmful experiments on hundreds of unsuspecting black men for forty years, until the research was shut down in the early 1970s.

Today, in the second decade of twenty-first century, the pernicious narrative that blacks are outsiders in science and medicine must be challenged, says Dr. Danielle N. Lee, assistant professor of biological sciences at Southern Illinois University. And having majority white participants in clinical trials only furthers the notion that "whiteness" is the default.

According to Lee, black individuals often see themselves disconnected from scientific and medical processes. "One of the critiques with science and medical research is that communities of color, and black communities in particular, regard ourselves as outsiders of science," Lee says. "We are othered."

Without increased minority participation, research will not accurately reflect the diversity of the general population.

"We are all human, but we are different, and yes, even different populations of people require modified medical responses," she points out.

Another obstacle is that many trials have health requirements that exclude black Americans, like not wanting individuals who have high blood pressure or a history of stroke. Considering that this group faces health disparities at a higher rate than whites, this eliminates eligibility for millions of potential participants.

One way to increase the diversity in sample participation without an FDA mandate is to include more black Americans in both volunteer and clinical roles during the research process to increase accountability in treatment, education, and advocacy.

"When more of us participate in clinical trials, we help build out the basic data sets that account for health disparities from the start, not after the fact," Lee says. She also suggests that researchers involve black patient representatives throughout the clinical trial process, from the study design to the interpretation of results.

"This allows for the black community to give insight on how to increase trial enrollment and help reduce stigma," she explains.

Thankfully, partnerships are popping up like the one between The Howard University's Cancer Center and Driver, a platform that connects cancer patients to treatment and trials. These sorts of targeted and culturally tailored efforts allow black patients to receive assistance from well-respected organizations.

Some observers suggest that the federal government and pharmaceutical industries must step up to address the gap.

However, some experts say that the black community should not be held solely responsible for solving a problem it did not cause. Instead, some observers suggest that the federal government and pharmaceutical industries must step up to address the gap.

According to Balls-Berry, socioeconomic barriers like transportation, time off work, and childcare related to trial participation must be removed. "These are real-world issues and yet many times researchers have not included these things in their budgets."

When asked to comment, a spokesperson for BIO, the world's largest biotech trade association, emailed the following statement:

"BIO believes that that our members' products and services should address the needs of a diverse population, and enhancing participation in clinical trials by a diverse patient population is a priority for BIO and our member companies. By investing in patient education to improve awareness of clinical trial opportunities, we can reduce disparities in clinical research to better reflect the country's changing demographics."

For my mother, the patient suffering from autoimmune disease, the need for broad participation in medical research is clear. "Without clinical trials, we would have less diagnosis and solutions to diseases," she says. "I think it's an underutilized resource."

Interview with Jamie Metzl: We need a global OS upgrade

Jamie Metzl, author of Hacking Darwin, shares his views with Leaps.org on the future of genetics, tech, healthcare and more.

In this Q&A, leading technology and healthcare futurist Jamie Metzl discusses a range of topics and trend lines that will unfold over the next several decades: whether a version of Moore's Law applies to genetic technologies, the ethics of genetic engineering, the dangers of gene hacking, the end of sex, and much more.

Metzl is a member of the WHO expert advisory committee on human genome editing and the bestselling author of Hacking Darwin.

The conversation was lightly edited by Leaps.org for style and length.

In Hacking Darwin, you describe how we may modify the human body with CRISPR technologies, initially to obtain unsurpassed sports performance and then to enhance other human characteristics. What would such power over human biology mean for the future of our civilization?

After nearly four billion years of evolution, our one species suddenly has the increasing ability to read, write, and hack the code of life. This will have massive implications across the board, including in human health and reproduction, plant and animal agriculture, energy and advanced materials, and data storage and computing, just to name a few. My book Hacking Darwin: Genetic Engineering and the Future of Humanity primarly explored how we are currently deploying and will increasingly use our capabilities to transform human life in novel ways. My next book, The Great Biohack: Recasting Life in an Age of Revolutionary Technology, coming out in May 2024, will examine the broader implications for all of life on Earth.

We humans will, over time, use these technologies on ourselves to solve problems and eventually to enhance our capabilities. We need to be extremely conservative, cautious, and careful in doing so, but doing so will almost certainly be part of our future as a species.

In electronics, Moore's law is an established theory that computing power doubles every 18 months. Is there any parallel to be drawn with genetic technologies?

The increase in speed and decrease in costs of genome sequencing have progressed far faster than Moore’s law. It took thirteen years and cost about a billion dollars to sequence the first human genome. Today it takes just a few hours and can cost as little as a hundred dollars to do a far better job. In 2012, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuel Charpentier published the basic science paper outlining the CRISPR-cas9 genome editing tool that would eventually win them the Nobel prize. Only six years later, the first CRISPR babies were born in China. If it feels like technology is moving ever-faster, that’s because it is.

Let's turn to the topic of aging. Do you think that the field of genetics will advance fast enough to eventually increase maximal lifespan for a child born this year? How about for a person who is currently age 50?

The science of aging is definitely real, but that doesn’t mean we will live forever. Aging is a biological process subject to human manipulation. Decades of animal research shows that. This does not mean we will live forever, but it does me we will be able to do more to expand our healthspans, the period of our lives where we are able to live most vigorously.

The first thing we need to do is make sure everyone on earth has access to the resources necessary to live up to their potential. I live in New York City, and I can take a ten minute subway ride to a neighborhood where the average lifespan is over a decade shorter than in mine. This is true within societies and between countries as well. Secondly, we all can live more like people in the Blue Zones, parts of the world where people live longer, on average, than the rest of us. They get regular exercise, eat healthy foods, have strong social connections, etc. Finally, we will all benefit, over time, from more scientific interventions to extend our healthspan. This may include small molecule drugs like metformin, rapamycin, and NAD+ boosters, blood serum infusions, and many other things.

Science fiction has depicted a future where we will never get sick again, stay young longer or become immortal. Assuming that any of this is remotely possible, should we be afraid of such changes, even if they seem positive in some regards, because we can’t understand the full implications at this point?

Not all of these promises will be realized in full, but we will use these technologies to help us live healthier, longer lives. We will never become immortal becasue nothing lasts forever. We will always get sick, even if the balance of diseases we face shifts over time, as it has always done. It is healthy, and absolutely necessary, that we feel both hope and fear about this future. If we only feel hope, we will blind ourselves to the very real potential downsides. If we only feel fear, we will deny ourselves the very meaningful benefits these technologies have the potential to provide.

A fascinating chapter in Hacking Darwin is entitled The End of Sex. And you see that as a good thing?

We humans will always be a sexually reproducing species, it’s just that we’ll reproduce increasingly less through the physical act of sex. We’re already seeing this with IVF. As the benefits of technology assisted reproduction increase relative to reproduction through the act of sex, many people will come to see assisted reproduction as a better way to reduce risk and, over time, possibly increase benefits. We’ll still have sex for all the other wonderful reasons we have it today, just less for reproduction. There will always be a critical place in our world for Italian romantics!

What are dangers of genetic hackers, perhaps especially if everyone’s DNA is eventually transcribed for medical purposes and available on the internet and in the cloud?

The sky is really the limit for how we can use gentic technologies to do things we may want, and the sky is also the limit for potential harms. It’s quite easy to imagine scenarios in which malevolent actors create synthetic pathogens designed to wreak havoc, or where people steal and abuse other people’s genetic information. It wouldn’t even need to be malevolent actors. Even well-intentioned researchers making unintended mistakes could cause real harm, as we may have seen with COVID-19 if, as appears likely to me, the pandemic stems for a research related incident]. That’s why we need strong governance and regulatory systems to optimize benefits and minimize potential harms. I was honored to have served on the World Health Organization Expert Advisory Committee on Human Genome Editing, were we developed a proposed framework for how this might best be achieved.

You foresee the equivalent of a genetic arms race between the world's most powerful countries. In what sense are genetic technologies similar to weapons?

Genetic technologies could be used to create incredibly powerful bioweapons or to build gene drives with the potential to crash entire ecosystems. That’s why thoughtful regulation is in order. Because the benefits of mastering and deploying these technologies are so great, there’s also a real danger of a genetics arms race. This could be extremely dangerous and will need to be prevented.

In your book, you express concern that states lacking Western conceptions of human rights are especially prone to misusing the science of genetics. Does this same concern apply to private companies? How much can we trust them to control and wield these technologies?

This is a conversation about science and technology but it’s really a conversation about values. If we don’t agree on what core values should be promoted, it will be nearly impossible to agree on what actions do and do not make sense. We need norms, laws, and values frameworks that apply to everyone, including governments, corporations, researchers, healthcare providers, DiY bio hobbyists, and everyone else.

We have co-evolved with our technology for a very long time. Many of our deepest beliefs have formed in that context and will continue to do so. But as we take for ourselves the powers we have attributed to our various gods, many of these beliefs will be challenged. We can not and must not jettison our beliefs in the face of technology, and must instead make sure our most cherished values guide the application of our most powerful technologies.

A conversation on international norms is in full swing in the field of AI, prompted by the release of ChatGPT4 earlier this year. Are there ways in which it’s inefficient, shortsighted or otherwise problematic for these discussions on gene technologies, AI and other advances to be occurring in silos? In addition to more specific guidelines, is there something to be gained from developing a universal set of norms and values that applies more broadly to all innovation?

AI is yet another technology where the potential to do great good is tied to the potential to inflict signifcant harm. It makes no sense that we tend to treat each technology on its own rather than looking at the entire category of challenges. For sure, we need to very rapidly ramp up our efforts with regard to AI norm-setting, regulations, and governance at all levels. But just doing that will be kind of like generating a flu vaccine for each individual flu strain. Far better to build a universal flu vaccine addressing common elements of all flu viruses of concern.

That’s why we also need to be far more deliberate in both building a global operating systems based around the mutual responsibilities of our global interdependence and, under that umbrella, a broader system for helping us govern and regulate revolutionary technologies. Such a process might begin with a large international conference, the equivalent of Rio 1992 for climate change, but then quickly work to establish and share best practices, help build parallel institutions in all countries so people and governamts can talk with each other, and do everything possible to maximize benefits and minimize risks at all levels in an ongoing and dynamic way.

At what point might genetic enhancements lead to a reclassfication of modified humans as another species?

We’ll still all be fellow humans for a very, very long time. We already have lots of variation between us. That is the essence of biology. Will some humans, at some point in the future, leave Earth and spend generations elsewhere? I believe so. In those new environments, humans will evolve, over time, differently than those if us who remain on this planet? This may sound like science fiction, but the sci-fi future is coming at us faster than most people realize.

Is the concept of human being changing?

Yes. It always has and always will.

Another big question raised in your book: what limits should we impose on the freedom to manipulate genetics?

Different societies will come to different conclusion on this critical question. I am sympathetic to the argument that people should have lots of say over their own bodies, which why I support abortion rights even though I recognize that an abortion can be a violent procedure. But it would be insane and self-defeating to say that individuals have an unlimited right to manipulate their own or their future children’s heritable genetics. The future of human life is all of our concern and must be regulated, albeit wisely.

In some cases, such as when we have the ability to prevent a deadly genetic disroder, it might be highly ethical to manipulate other human beings. In other circumstances, the genetic engineering of humans might be highly unethical. The key point is to avoid asking this question in a binary manner. We need to weigh the costs and benefits of each type of intervention. We need societal and global infrastrucutres to do that well. We don’t yet have those but we need them badly.

Can you tell us more about your next book?

The Great Biohack: Recasting Lifee in an Age of Revolutionary Technology, will come out in May 2024. It explores what the intersecting AI, genetics, and biotechnology revolutions will mean for the future of life on earth, including our healthcare, agriculture, industry, computing, and everything else. We are at a transitional moment for life on earth, equivalent to the dawn of agriculture, electricity, and industrialization. The key differentiator between better and worse outcomes is what we do today, at this early stage of this new transformation. The book describes what’s happening, what’s at stake, and what we each and all can and, frankly, must do to build the type of future we’d like to inhabit.

You’ve been a leader of international efforts calling for a full investigation into COVID-19 origins and are the founder of the global movement OneShared.World. What problem are you trying to solve through OneShared.World?

The biggest challenge we face today is the mismatch between the nature of our biggest problems, global and common, and the absence of a sufficient framework for addressing that entire category of challenges. The totally avoidable COVID-19 pandemic is one example of the extremet costs of the status quo. OneShared.World is our effort to fight for an upgrade in our world’s global operating system, based around the mutual responsibilities of interdependence. We’ve had global OS upgrades before after the Thirty Years War and after World War II, but wouldn’t it be better to make the necessary changes now to prevent a crisis of that level stemming from a nuclear war, ecosystem collapse, or deadlier synthetic biology pandemic rather than waiting until after? Revolutionary science is a global issue that must be wisely managed at every level if it is to be wisely managed at all.

How do we ensure that revolutionary technologies benefit humanity instead of undermining it?

That is the essential question. It’s why I’ve written Hacking Darwin, am writing The Great Biohack, and doing the rest of my work. If we want scietific revolutions to help, rather than hurt, us, we must all play a role building that future. This isn’t just a conversation about science, it’s about how we can draw on our most cherished values to guide the optimal development of science and technology for the common good. That must be everyone’s business.

Portions of this interview were first published in Grassia (Italy) and Zen Portugal.

Jamie Metzl is one of the world’s leading technology and healthcare futurists and author of the bestselling book, Hacking Darwin: Genetic Engineering and the Future of Humanity, which has been translated into 15 languages. In 2019, he was appointed to the World Health Organization expert advisory committee on human genome editing. Jamie is a faculty member of Singularity University and NextMed Health, a Senior Fellow of the Atlantic Council, and Founder and Chair of the global social movement, OneShared.World.

Called “the original COVID-19 whistleblower,” his pioneering role advocating for a full investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic has been featured in 60 Minutes, the New York Times, and most major media across the globe, and he was the lead witness in the first congressional hearings on this topic. Jamie previously served in the U.S. National Security Council, State Department, and Senate Foreign Relations Committee and with the United Nations in Cambodia. Jamie appears regularly on national and international media and his syndicated columns and other writing in science, technology, and global affairs are featured in publications around the world.

Jamie sits on advisory boards for multiple biotechnology and other companies and is Special Strategist to the WisdomTree BioRevolution Exchange Traded Fund. In addition to Hacking Darwin, he is author of a history of the Cambodian genocide, the historical novel The Depths of the Sea, and the genetics sci-fi thrillers Genesis Code and Eternal Sonata. His next book, The Great Biohack: Recasting Life in an age of Revolutionary Technology, will be published by Hachette in May 2024. Jamie holds a Ph.D. from Oxford, a law degree from Harvard, and an undergraduate degree from Brown and is an avid ironman triathlete and ultramarathon runner.

Researchers are looking to engineer chocolate with less oil, which could reduce some of its detriments to health.

Creamy milk with velvety texture. Dark with sprinkles of sea salt. Crunchy hazelnut-studded chunks. Chocolate is a treat that appeals to billions of people worldwide, no matter the age. And it’s not only the taste, but the feel of a chocolate morsel slowly melting in our mouths—the smoothness and slipperiness—that’s part of the overwhelming satisfaction. Why is it so enjoyable?

That’s what an interdisciplinary research team of chocolate lovers from the University of Leeds School of Food Science and Nutrition and School of Mechanical Engineering in the U.K. resolved to study in 2021. They wanted to know, “What is making chocolate that desirable?” says Siavash Soltanahmadi, one of the lead authors of a new study about chocolates hedonistic quality.

Besides addressing the researchers’ general curiosity, their answers might help chocolate manufacturers make the delicacy even more enjoyable and potentially healthier. After all, chocolate is a billion-dollar industry. Revenue from chocolate sales, whether milk or dark, is forecasted to grow 13 percent by 2027 in the U.K. In the U.S., chocolate and candy sales increased by 11 percent from 2020 to 2021, on track to reach $44.9 billion by 2026. Figuring out how chocolate affects the human palate could up the ante even more.

Building a 3D tongue

The team began by building a 3D tongue to analyze the physical process by which chocolate breaks down inside the mouth.

As part of the effort, reported earlier this year in the scientific journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, the team studied a large variety of human tongues with the intention to build an “average” 3D model, says Soltanahmadi, a lubrication scientist. When it comes to edible substances, lubrication science looks at how food feels in the mouth and can help design foods that taste better and have more satisfying texture or health benefits.

There are variations in how people enjoy chocolate; some chew it while others “lick it” inside their mouths.

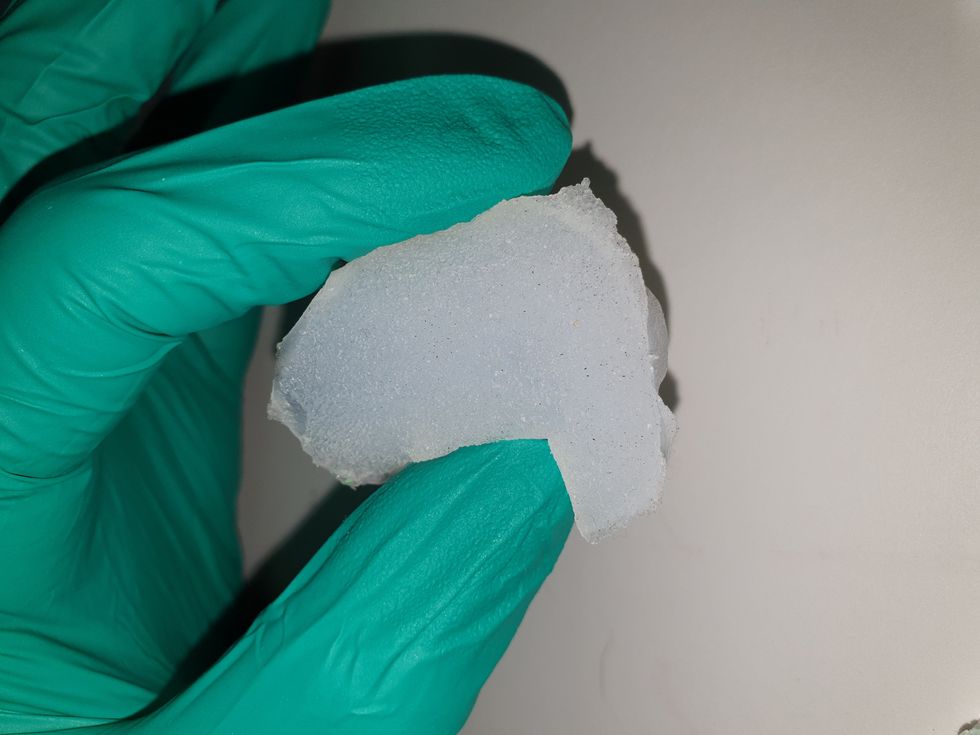

Tongue impressions from human participants studied using optical imaging helped the team build a tongue with key characteristics. “Our tongue is not a smooth muscle, it’s got some texture, it has got some roughness,” Soltanahmadi says. From those images, the team came up with a digital design of an average tongue and, using 3D printed molds, built a “mimic tongue.” They also added elastomers—such as silicone or polyurethane—to mimic the roughness, the texture and the mechanical properties of a real tongue. “Wettability" was another key component of the 3D tongue, Soltanahmadi says, referring to whether a surface mixes with water (hydrophilic) or, in the case of oil, resists it (hydrophobic).

Notably, the resulting artificial 3D-tongues looked nothing like the human version, but they were good mimics. The scientists also created “testing kits” that produced data on various physical parameters. One such parameter was viscosity, the measure of how gooey a food or liquid is — honey is more viscous compared to water, for example. Another was tribology, which defines how slippery something is — high fat yogurt is more slippery than low fat yogurt; milk can be more slippery than water. The researchers then mixed chocolate with artificial saliva and spread it on the 3D tongue to measure the tribology and the viscosity. From there they were able to study what happens inside the mouth when we eat chocolate.

The team focused on the stages of lubrication and the location of the fat in the chocolate, a process that has rarely been researched.

The artificial 3D-tongues look nothing like human tongues, but they function well enough to do the job.

Courtesy Anwesha Sarkar and University of Leeds

The oral processing of chocolate

We process food in our mouths in several stages, Soltanahmadi says. And there is variation in these stages depending on the type of food. So, the oral processing of a piece of meat would be different from, say, the processing of jelly or popcorn.

There are variations with chocolate, in particular; some people chew it while others use their tongues to explore it (within their mouths), Soltanahmadi explains. “Usually, from a consumer perspective, what we find is that if you have a luxury kind of a chocolate, then people tend to start with licking the chocolate rather than chewing it.” The researchers used a luxury brand of dark chocolate and focused on the process of licking rather than chewing.

As solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave.

Understanding the make-up of the chocolate was also an important step in the study. “Chocolate is a composite material. So, it has cocoa butter, which is oil, it has some particles in it, which is cocoa solid, and it has sugars," Soltanahmadi says. "Dark chocolate has less oil, for example, and less sugar in it, most of the time."

The researchers determined that the oral processing of chocolate begins as soon as it enters a person’s mouth; it starts melting upon exposure to one’s body temperature, even before the tongue starts moving, Soltanahmadi says. Then, lubrication begins. “[Saliva] mixes with the oily chocolate and it makes an emulsion." An emulsion is a fluid with a watery (or aqueous) phase and an oily phase. As chocolate breaks down in the mouth, that solid piece turns into a smooth emulsion with a fatty film. “The oil from the chocolate becomes droplets in a continuous aqueous phase,” says Soltanahmadi. In other words, as solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette, creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave, says Soltanahmadi.

Finding the sweet spot

After determining how chocolate is orally processed, the research team wanted to find the exact sweet spot of the breakdown of solid cocoa particles and fat as they are released into the mouth. They determined that the epicurean pleasure comes only from the chocolate's outer layer of fat; the secondary fatty layers inside the chocolate don’t add to the sensation. It was this final discovery that helped the team determine that it might be possible to produce healthier chocolate that would contain less oil, says Soltanahmadi. And therefore, less fat.

Rongjia Tao, a physicist at Temple University in Philadelphia, thinks the Leeds study and the concept behind it is “very interesting.” Tao, himself, did a study in 2016 and found he could reduce fat in milk chocolate by 20 percent. He believes that the Leeds researchers’ discovery about the first layer of fat being more important for taste than the other layer can inform future chocolate manufacturing. “As a scientist I consider this significant and an important starting point,” he says.

Chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research found that plant polyphenols can protect against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular ad neurodegenerative diseases.

Not everyone thinks it’s a good idea, such as chef Michael Antonorsi, founder and owner of Chuao Chocolatier, one of the leading chocolate makers in the U.S. First, he says, “cacao fat is definitely a good fat.” Second, he’s not thrilled that science is trying to interfere with nature. “Every time we've tried to intervene and change nature, we get things out of balance,” says Antonorsi. “There’s a reason cacao is botanically known as food of the gods. The botanical name is the Theobroma cacao: Theobroma in ancient Greek, Theo is God and Brahma is food. So it's a food of the gods,” Antonorsi explains. He’s doubtful that a chocolate made only with a top layer of fat will produce the same epicurean satisfaction. “You're not going to achieve the same sensation because that surface fat is going to dissipate and there is no fat from behind coming to take over,” he says.

Without layers of fat, Antonorsi fears the deeply satisfying experiential part of savoring chocolate will be lost. The University of Leeds team, however, thinks that it may be possible to make chocolate healthier - when consumed in limited amounts - without sacrificing its taste. They believe the concept of less fatty but no less slick chocolate will resonate with at least some chocolate-makers and consumers, too.

Chocolate already contains some healthful compounds. Its cocoa particles have “loads of health benefits,” says Soltanahmadi. Dark chocolate usually has more cocoa than milk chocolate. Some experts recommend that dark chocolate should contain at least 70 percent cocoa in order for it to offer some health benefit. Research has shown that the cocoa in chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research has shown that consuming plant polyphenols can be protective against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

“So keeping the healthy part of it and reducing the oily part of it, which is not healthy, but is giving you that indulgence of it … that was the final aim,” Soltanahmadi says. He adds that the team has been approached by individuals in the chocolate industry about their research. “Everyone wants to have a healthy chocolate, which at the same time tastes brilliant and gives you that self-indulging experience.”