Why Blindness Will Be the First Disorder Cured by Futuristic Treatments

A blind man with a cane goes for a walk at sunset. (© Prazis/Fotolia)

Stem cells and gene therapy were supposed to revolutionize biomedicine around the turn of the millennium and provide relief for desperate patients with incurable diseases. But for many, progress has been frustratingly slow. We still cannot, for example, regenerate damaged organs like a salamander regrows its tail, and genome engineering is more complicated than cutting and pasting letters in a word document.

"There are a number of things that make [the eye] ideal for new experimental therapies which are not true necessarily in other organs."

For blind people, however, the future of medicine is one step closer to reality. In December, the FDA approved the first gene therapy for an inherited disease—a mutation in the gene RPE65 that causes a rare form of blindness. Several clinical trials also show promise for treating various forms of retinal degeneration using stem cells.

"It's not surprising that the first gene therapy that was approved by the FDA was a therapy in the eye," says Bruce Conklin, a senior investigator at the San Francisco-based Gladstone Institutes, a nonprofit life science research organization, and a professor in the Medical Genetics and Molecular Pharmacology department at the University of California, San Francisco. "There are a number of things that make it ideal for new experimental therapies which are not true necessarily in other organs."

Physicians can easily see into the eye to check if a procedure worked or if it's causing problems. "The imaging technology within the eye is really unprecedented. You can't do this in someone's spinal cord or someone's brain cells or immune system," says Conklin, who is also deputy director of the Innovative Genomics Institute.

There's also a built-in control: researchers can test an intervention on one eye first. What's more, if something goes wrong, the risk of mortality is low, especially when compared to experimenting on the heart or brain. Most types of blindness are currently incurable, so the risk-to-reward ratio for patients is high. If a problem arises with the treatment their eyesight could get worse, but if they do nothing their vision will likely decline anyway. And if the treatment works, they may be able to see for the first time in years.

Gene Therapy

An additional appeal for testing gene therapy in the eye is the low risk for off-target effects, in which genome edits could result in unintended changes to other genes or in other cell types. There are a number of genes that are solely expressed in the eye and not in any other part of the body. Manipulating those genes will only affect cells in the eye, so concerns about the impact on other organs are minimal.

Ninety-three percent of patients who received the injection had improved vision just one month after treatment.

RPE65 is one such gene. It creates an enzyme that helps the eye convert light into an electrical signal that travels back to the brain. Patients with the mutation don't produce the enzyme, so visual signals are not processed. However, the retinal cells in the eye remain healthy for years; if you can restore the missing enzyme you can restore vision.

The newly approved therapy, developed by Spark Therapeutics, uses a modified virus to deliver RPE65 into the eye. A retinal surgeon injects the virus, which has been specially engineered to remove its disease-causing genes and instead carry the correct RPE65 gene, into the retina. There, it is sucked up by retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. The RPE cells are a particularly good target for injection because their job is to eat up and recycle rogue particles. Once inside the cell, the virus slips into the nucleus and releases the DNA. The RPE65 gene then goes to work, using the cell's normal machinery to produce the needed enzyme.

In the most recent clinical trial, 93 percent of patients who received the injection—who range in age from 4 to 44—had improved vision just one month after treatment. So far, the benefits have lasted at least two years.

"It's an exciting time for this class of diseases, where these people have really not had treatments," says Spark president and co-founder, Katherine High. "[Gene therapy] affords the possibility of treatment for diseases that heretofore other classes of therapeutics really have not been able to help."

Stem Cells

Another benefit of the eye is its immune privilege. In order to let light in, the eye must remain transparent. As a result, its immune system is dampened so that it won't become inflamed if outside particles get in. This means the eye is much less likely to reject cell transplants, so patients do not need to take immunosuppressant drugs.

One study generating buzz is a clinical trial in Japan that is the first and, so far, only test of induced pluripotent stem cells in the eye.

Henry Klassen, an assistant professor at UC Irvine, is taking advantage of the eye's immune privilege to transplant retinal progenitor cells into the eye to treat retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited disease affecting about 1 in 4000 people that eventually causes the retina to degenerate. The disease can stem from dozens of different genetic mutations, but the result is the same: RPE cells die off over the course of a few decades, leaving the patient blind by middle age. It is currently incurable.

Retinal progenitor cells are baby retinal cells that develop naturally from stem cells and will turn into one of several types of adult retinal cells. When transplanted into a patient's eye, the progenitor cells don't replace the lost retinal cells, but they do secrete proteins and enzymes essential for eye health.

"At the stage we get the retinal tissue it's immature," says Klassen. "They still have some flexibility in terms of which mature cells they can turn into. It's that inherent flexibility that gives them a lot of power when they're put in the context of a diseased retina."

Klassen's spin-off company, jCyte, sponsored the clinical trial with support from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. The results from the initial study haven't been published yet, but Klassen says he considers it a success. JCyte is now embarking on a phase two trial to assess improvements in vision after the treatment, which will wrap up in 2021.

Another study generating buzz is a clinical trial in Japan that is the first and, so far, only test of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) in the eye. iPSC are created by reprogramming a patient's own skin cells into stem cells, circumventing any controversy around embryonic stem cell sources. In the trial, led by Masayo Takahashi at RIKEN, the scientists transplant retinal pigment epithelial cells created from iPSC into the retinas of patients with age-related macular degeneration. The first woman to receive the treatment is doing well, and her vision is stable. However, the second patient suffered a swollen retina as a result of the surgery. Despite this recent setback, Takahashi said last week that the trial would continue.

Botched Jobs

Although recent studies have provided patients with renewed hope, the field has not been without mishap. Most notably, an article in the New England Journal of Medicine last March described three patients who experienced severe side effects after receiving stem cell injections from a Florida clinic to treat age-related macular degeneration. Following the initial article, other reports came out about similar botched treatments. Lawsuits have been filed against US Stem Cell, the clinic that conducted the procedure, and the FDA sent them a warning letter with a long list of infractions.

"One red flag is that the clinics charge patients to take part in the treatment—something extremely unusual for legitimate clinical trials."

Ajay Kuriyan, an ophthalmologist and retinal specialist at the University of Rochester who wrote the paper, says that because details about the Florida trial are scarce, it's hard to say why the treatment caused the adverse reaction. His guess is that the stem cells were poorly prepared and not up to clinical standards.

Klassen agrees that small clinics like US Stem Cell do not offer the same caliber of therapy as larger clinical trials. "It's not the same cells and it's not the same technique and it's not the same supervision and it's not under FDA auspices. It's just not the same thing," he says. "Unfortunately, to the patient it might sound the same, and that's the tragedy for me."

For patients who are interested in joining a trial, Kuriyan listed a few things to watch out for. "One red flag is that the clinics charge patients to take part in the treatment—something extremely unusual for legitimate clinical trials," he says. "Another big red flag is doing the procedure in both eyes" at the same time. Third, if the only treatment offered is cell therapy. "These clinics tend to be sort of stand-alone clinics, and that's not very common for an actual big research study of this scale."

Despite the recent scandal, Klassen hopes that the success of his trial and others will continue to push the field forward. "It just takes so many decades to move this stuff along, even when you're trying to simplify it as much as possible," he says. "With all the heavy lifting that's been done, I hope the world's got the patience to get this through."

Jamie Rettinger with his now fiance Amie Purnel-Davis, who helped him through the clinical trial.

Jamie Rettinger was still in his thirties when he first noticed a tiny streak of brown running through the thumbnail of his right hand. It slowly grew wider and the skin underneath began to deteriorate before he went to a local dermatologist in 2013. The doctor thought it was a wart and tried scooping it out, treating the affected area for three years before finally removing the nail bed and sending it off to a pathology lab for analysis.

"I have some bad news for you; what we removed was a five-millimeter melanoma, a cancerous tumor that often spreads," Jamie recalls being told on his return visit. "I'd never heard of cancer coming through a thumbnail," he says. None of his doctors had ever mentioned it either. "I just thought I was being treated for a wart." But nothing was healing and it continued to bleed.

A few months later a surgeon amputated the top half of his thumb. Lymph node biopsy tested negative for spread of the cancer and when the bandages finally came off, Jamie thought his medical issues were resolved.

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. About 85,000 people are diagnosed with it each year in the U.S. and more than 8,000 die of the cancer when it spreads to other parts of the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There are two peaks in diagnosis of melanoma; one is in younger women ages 30-40 and often is tied to past use of tanning beds; the second is older men 60+ and is related to outdoor activity from farming to sports. Light-skinned people have a twenty-times greater risk of melanoma than do people with dark skin.

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" --Diwakar Davar.

Jamie had a follow up PET scan about six months after his surgery. A suspicious spot on his lung led to a biopsy that came back positive for melanoma. The cancer had spread. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody (nivolumab/Opdivo®) didn't prove effective and he was referred to the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, a four-hour drive from his home in western Ohio.

An alternative monoclonal antibody treatment brought on such bad side effects, diarrhea as often as 15 times a day, that it took more than a week of hospitalization to stabilize his condition. The only options left were experimental approaches in clinical trials.

Early research

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" with a cure rate in the single digits, says Diwakar Davar, 39, an oncologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center who specializes in skin cancer. That began to change in 2010 with introduction of the first immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, to treat cancer. The antibodies attach to PD-1, a receptor on the surface of T cells of the immune system and on cancer cells. Antibody treatment boosted the melanoma cure rate to about 30 percent. The search was on to understand why some people responded to these drugs and others did not.

At the same time, there was a growing understanding of the role that bacteria in the gut, the gut microbiome, plays in helping to train and maintain the function of the body's various immune cells. Perhaps the bacteria also plays a role in shaping the immune response to cancer therapy.

One clue came from genetically identical mice. Animals ordered from different suppliers sometimes responded differently to the experiments being performed. That difference was traced to different compositions of their gut microbiome; transferring the microbiome from one animal to another in a process known as fecal transplant (FMT) could change their responses to disease or treatment.

When researchers looked at humans, they found that the patients who responded well to immunotherapies had a gut microbiome that looked like healthy normal folks, but patients who didn't respond had missing or reduced strains of bacteria.

Davar and his team knew that FMT had a very successful cure rate in treating the gut dysbiosis of Clostridioides difficile, a persistant intestinal infection, and they wondered if a fecal transplant from a patient who had responded well to cancer immunotherapy treatment might improve the cure rate of patients who did not originally respond to immunotherapies for melanoma.

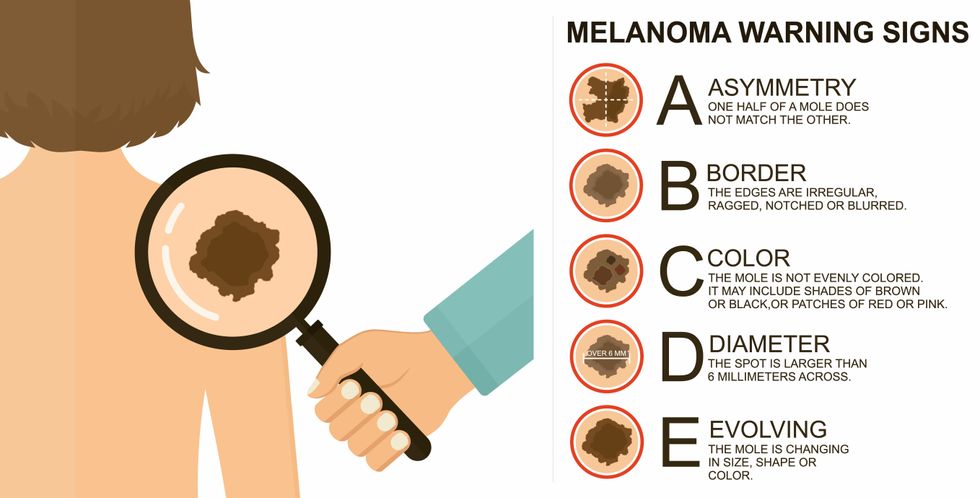

The ABCDE of melanoma detection

Adobe Stock

Clinical trial

"It was pretty weird, I was totally blasted away. Who had thought of this?" Jamie first thought when the hypothesis was explained to him. But Davar's explanation that the procedure might restore some of the beneficial bacterial his gut was lacking, convinced him to try. He quickly signed on in October 2018 to be the first person in the clinical trial.

Fecal donations go through the same safety procedures of screening for and inactivating diseases that are used in processing blood donations to make them safe for transfusion. The procedure itself uses a standard hollow colonoscope designed to screen for colon cancer and remove polyps. The transplant is inserted through the center of the flexible tube.

Most patients are sedated for procedures that use a colonoscope but Jamie doesn't respond to those drugs: "You can't knock me out. I was watching them on the TV going up my own butt. It was kind of unreal at that point," he says. "There were about twelve people in there watching because no one had seen this done before."

A test two weeks after the procedure showed that the FMT had engrafted and the once-missing bacteria were thriving in his gut. More importantly, his body was responding to another monoclonal antibody (pembrolizumab/Keytruda®) and signs of melanoma began to shrink. Every three months he made the four-hour drive from home to Pittsburgh for six rounds of treatment with the antibody drug.

"We were very, very lucky that the first patient had a great response," says Davar. "It allowed us to believe that even though we failed with the next six, we were on the right track. We just needed to tweak the [fecal] cocktail a little better" and enroll patients in the study who had less aggressive tumor growth and were likely to live long enough to complete the extensive rounds of therapy. Six of 15 patients responded positively in the pilot clinical trial that was published in the journal Science.

Davar believes they are beginning to understand the biological mechanisms of why some patients initially do not respond to immunotherapy but later can with a FMT. It is tied to the background level of inflammation produced by the interaction between the microbiome and the immune system. That paper is not yet published.

Surviving cancer

It has been almost a year since the last in his series of cancer treatments and Jamie has no measurable disease. He is cautiously optimistic that his cancer is not simply in remission but is gone for good. "I'm still scared every time I get my scans, because you don't know whether it is going to come back or not. And to realize that it is something that is totally out of my control."

"It was hard for me to regain trust" after being misdiagnosed and mistreated by several doctors he says. But his experience at Hillman helped to restore that trust "because they were interested in me, not just fixing the problem."

He is grateful for the support provided by family and friends over the last eight years. After a pause and a sigh, the ruggedly built 47-year-old says, "If everyone else was dead in my family, I probably wouldn't have been able to do it."

"I never hesitated to ask a question and I never hesitated to get a second opinion." But Jamie acknowledges the experience has made him more aware of the need for regular preventive medical care and a primary care physician. That person might have caught his melanoma at an earlier stage when it was easier to treat.

Davar continues to work on clinical studies to optimize this treatment approach. Perhaps down the road, screening the microbiome will be standard for melanoma and other cancers prior to using immunotherapies, and the FMT will be as simple as swallowing a handful of freeze-dried capsules off the shelf rather than through a colonoscopy. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral fecal microbiota product for C. difficile, hopefully paving the way for more.

An older version of this hit article was first published on May 18, 2021

All organisms can repair damaged tissue, but none do it better than salamanders and newts. A surprising area of science could tell us how they manage this feat - and perhaps even help us develop a similar ability.

All organisms have the capacity to repair or regenerate tissue damage. None can do it better than salamanders or newts, which can regenerate an entire severed limb.

That feat has amazed and delighted man from the dawn of time and led to endless attempts to understand how it happens – and whether we can control it for our own purposes. An exciting new clue toward that understanding has come from a surprising source: research on the decline of cells, called cellular senescence.

Senescence is the last stage in the life of a cell. Whereas some cells simply break up or wither and die off, others transition into a zombie-like state where they can no longer divide. In this liminal phase, the cell still pumps out many different molecules that can affect its neighbors and cause low grade inflammation. Senescence is associated with many of the declining biological functions that characterize aging, such as inflammation and genomic instability.

Oddly enough, newts are one of the few species that do not accumulate senescent cells as they age, according to research over several years by Maximina Yun. A research group leader at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology and Genetics, in Dresden, Germany, Yun discovered that senescent cells were induced at some stages of regeneration of the salamander limb, “and then, as the regeneration progresses, they disappeared, they were eliminated by the immune system,” she says. “They were present at particular times and then they disappeared.”

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states.

Previous research on senescence in aging had suggested, logically enough, that applying those cells to the stump of a newly severed salamander limb would slow or even stop its regeneration. But Yun stood that idea on its head. She theorized that senescent cells might also play a role in newt limb regeneration, and she tested it by both adding and removing senescent cells from her animals. It turned out she was right, as the newt limbs grew back faster than normal when more senescent cells were included.

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states, which could then be turned into progenitors, a cell type in between stem cells and specialized cells, needed to regrow the muscle tissue of the missing limb. “We think that this ability to dedifferentiate is intrinsically a big part of why salamanders can regenerate all these very complex structures, which other organisms cannot,” she explains.

Yun sees regeneration as a two part problem. First, the cells must be able to sense that their neighbors from the lost limb are not there anymore. Second, they need to be able to produce the intermediary progenitors for regeneration, , to form what is missing. “Molecularly, that must be encoded like a 3D map,” she says, otherwise the new tissue might grow back as a blob, or liver, or fin instead of a limb.

Wound healing

Another recent study, this time at the Mayo Clinic, provides evidence supporting the role of senescent cells in regeneration. Looking closely at molecules that send information between cells in the wound of a mouse, the researchers found that senescent cells appeared near the start of the healing process and then disappeared as healing progressed. In contrast, persistent senescent cells were the hallmark of a chronic wound that did not heal properly. The function and significance of senescence cells depended on both the timing and the context of their environment.

The paper suggests that senescent cells are not all the same. That has become clearer as researchers have been able to identify protein markers on the surface of some senescent cells. The patterns of these proteins differ for some senescent cells compared to others. In biology, such physical differences suggest functional differences, so it is becoming increasingly likely there are subsets of senescent cells with differing functions that have not yet been identified.

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes.

Scientists initially thought that senescent cells couldn’t play a role in regeneration because they could no longer reproduce, says Anthony Atala, a practicing surgeon and bioengineer who leads the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina. But Yun’s study points in the other direction. “What this paper shows clearly is that these cells have the potential to be involved in tissue regeneration [in newts]. The question becomes, will these cells be able to do the same in humans.”

As our knowledge of senescent cells increases, Atala thinks we need to embrace a new analogy to help understand them: humans in retirement. They “have acquired a lot of wisdom throughout their whole life and they can help younger people and mentor them to grow to their full potential. We're seeing the same thing with these cells,” he says. They are no longer putting energy into their own reproduction, but the signaling molecules they secrete “can help other cells around them to regenerate.”

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes. If so, it seems that our genes are unable to express this ability, perhaps as part of a tradeoff in acquiring other traits. It is a fertile area of research.

Dedifferentiation is likely to become an important process in the field of regenerative medicine. One extreme example: a lab has been able to turn back the clock and reprogram adult male skin cells into female eggs, a potential milestone in reproductive health. It will be more difficult to control just how far back one wishes to go in the cell's dedifferentiation – part way or all the way back into a stem cell – and then direct it down a different developmental pathway. Yun is optimistic we can learn these tricks from newts.

Senolytics

A growing field of research is using drugs called senolytics to remove senescent cells and slow or even reverse disease of aging.

“Senolytics are great, but senolytics target different types of senescence,” Yun says. “If senescent cells have positive effects in the context of regeneration, of wound healing, then maybe at the beginning of the regeneration process, you may not want to take them out for a little while.”

“If you look at pretty much all biological systems, too little or too much of something can be bad, you have to be in that central zone” and at the proper time, says Atala. “That's true for proteins, sugars, and the drugs that you take. I think the same thing is true for these cells. Why would they be different?”

Our growing understanding that senescence is not a single thing but a variety of things likely means that effective senolytic drugs will not resemble a single sledge hammer but more a carefully manipulated scalpel where some types of senescent cells are removed while others are added. Combinations and timing could be crucial, meaning the difference between regenerating healthy tissue, a scar, or worse.