Can blockchain help solve the Henrietta Lacks problem?

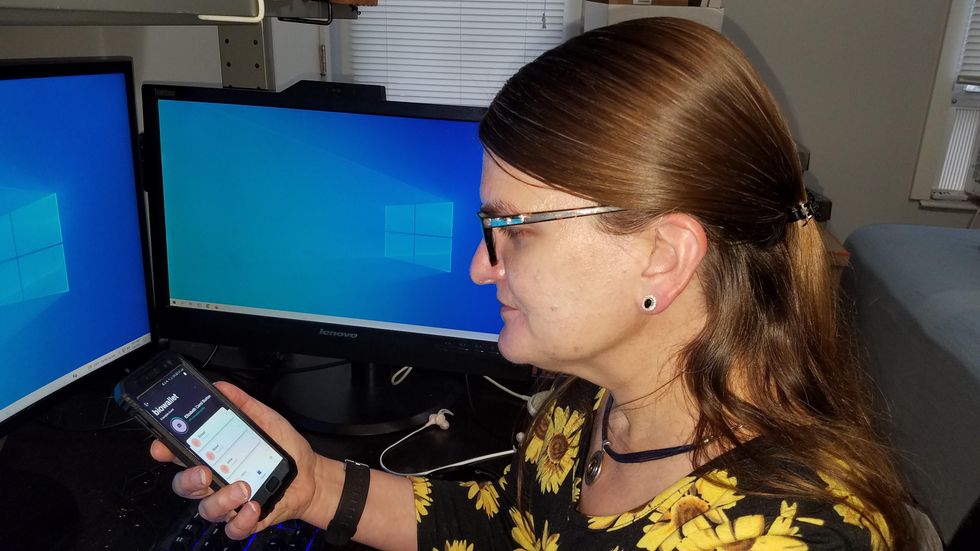

Marielle Gross, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, shows patients a new app that tracks how their samples are used during biomedical research.

Science has come a long way since Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman from Baltimore, succumbed to cervical cancer at age 31 in 1951 -- only eight months after her diagnosis. Since then, research involving her cancer cells has advanced scientific understanding of the human papilloma virus, polio vaccines, medications for HIV/AIDS and in vitro fertilization.

Today, the World Health Organization reports that those cells are essential in mounting a COVID-19 response. But they were commercialized without the awareness or permission of Lacks or her family, who have filed a lawsuit against a biotech company for profiting from these “HeLa” cells.

While obtaining an individual's informed consent has become standard procedure before the use of tissues in medical research, many patients still don’t know what happens to their samples. Now, a new phone-based app is aiming to change that.

Tissue donors can track what scientists do with their samples while safeguarding privacy, through a pilot program initiated in October by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics and the University of Pittsburgh’s Institute for Precision Medicine. The program uses blockchain technology to offer patients this opportunity through the University of Pittsburgh's Breast Disease Research Repository, while assuring that their identities remain anonymous to investigators.

A blockchain is a digital, tamper-proof ledger of transactions duplicated and distributed across a computer system network. Whenever a transaction occurs with a patient’s sample, multiple stakeholders can track it while the owner’s identity remains encrypted. Special certificates called “nonfungible tokens,” or NFTs, represent patients’ unique samples on a trusted and widely used blockchain that reinforces transparency.

Blockchain could be used to notify people if cancer researchers discover that they have certain risk factors.

“Healthcare is very data rich, but control of that data often does not lie with the patient,” said Julius Bogdan, vice president of analytics for North America at the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), a Chicago-based global technology nonprofit. “NFTs allow for the encapsulation of a patient’s data in a digital asset controlled by the patient.” He added that this technology enables a more secure and informed method of participating in clinical and research trials.

Without this technology, de-identification of patients’ samples during biomedical research had the unintended consequence of preventing them from discovering what researchers find -- even if that data could benefit their health. A solution was urgently needed, said Marielle Gross, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive science and bioethics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

“A researcher can learn something from your bio samples or medical records that could be life-saving information for you, and they have no way to let you or your doctor know,” said Gross, who is also an affiliate assistant professor at the Berman Institute. “There’s no good reason for that to stay the way that it is.”

For instance, blockchain could be used to notify people if cancer researchers discover that they have certain risk factors. Gross estimated that less than half of breast cancer patients are tested for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 — tumor suppressor genes that are important in combating cancer. With normal function, these genes help prevent breast, ovarian and other cells from proliferating in an uncontrolled manner. If researchers find mutations, it’s relevant for a patient’s and family’s follow-up care — and that’s a prime example of how this newly designed app could play a life-saving role, she said.

Liz Burton was one of the first patients at the University of Pittsburgh to opt for the app -- called de-bi, which is short for decentralized biobank -- before undergoing a mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer in November, after it was diagnosed on a routine mammogram. She often takes part in medical research and looks forward to tracking her tissues.

“Anytime there’s a scientific experiment or study, I’m quick to participate -- to advance my own wellness as well as knowledge in general,” said Burton, 49, a life insurance service representative who lives in Carnegie, Pa. “It’s my way of contributing.”

Liz Burton was one of the first patients at the University of Pittsburgh to opt for the app before undergoing a mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer.

Liz Burton

The pilot program raises the issue of what investigators may owe study participants, especially since certain populations, such as Black and indigenous peoples, historically were not treated in an ethical manner for scientific purposes. “It’s a truly laudable effort,” Tamar Schiff, a postdoctoral fellow in medical ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, said of the endeavor. “Research participants are beautifully altruistic.”

Lauren Sankary, a bioethicist and associate director of the neuroethics program at Cleveland Clinic, agrees that the pilot program provides increased transparency for study participants regarding how scientists use their tissues while acknowledging individuals’ contributions to research.

However, she added, “it may require researchers to develop a process for ongoing communication to be responsive to additional input from research participants.”

Peter H. Schwartz, professor of medicine and director of Indiana University’s Center for Bioethics in Indianapolis, said the program is promising, but he wonders what will happen if a patient has concerns about a particular research project involving their tissues.

“I can imagine a situation where a patient objects to their sample being used for some disease they’ve never heard about, or which carries some kind of stigma like a mental illness,” Schwartz said, noting that researchers would have to evaluate how to react. “There’s no simple answer to those questions, but the technology has to be assessed with an eye to the problems it could raise.”

To truly make a difference, blockchain must enable broad consent from patients, not just de-identification.

As a result, researchers may need to factor in how much information to share with patients and how to explain it, Schiff said. There are also concerns that in tracking their samples, patients could tell others what they learned before researchers are ready to publicly release this information. However, Bogdan, the vice president of the HIMSS nonprofit, believes only a minimal study identifier would be stored in an NFT, not patient data, research results or any type of proprietary trial information.

Some patients may be confused by blockchain and reluctant to embrace it. “The complexity of NFTs may prevent the average citizen from capitalizing on their potential or vendors willing to participate in the blockchain network,” Bogdan said. “Blockchain technology is also quite costly in terms of computational power and energy consumption, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.”

In addition, this nascent, groundbreaking technology is immature and vulnerable to data security flaws, disputes over intellectual property rights and privacy issues, though it does offer baseline protections to maintain confidentiality. To truly make a difference, blockchain must enable broad consent from patients, not just de-identification, said Robyn Shapiro, a bioethicist and founding attorney at Health Sciences Law Group near Milwaukee.

The Henrietta Lacks story is a prime example, Shapiro noted. During her treatment for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins, Lacks’s tissue was de-identified (albeit not entirely, because her cell line, HeLa, bore her initials). After her death, those cells were replicated and distributed for important and lucrative research and product development purposes without her knowledge or consent.

Nonetheless, Shapiro thinks that the initiative by the University of Pittsburgh and Johns Hopkins has potential to solve some ethical challenges involved in research use of biospecimens. “Compared to the system that allowed Lacks’s cells to be used without her permission, Shapiro said, “blockchain technology using nonfungible tokens that allow patients to follow their samples may enhance transparency, accountability and respect for persons who contribute their tissue and clinical data for research.”

Read more about laws that have prevented people from the rights to their own cells.

Here's how one doctor overcame extraordinary odds to help create the birth control pill

Dr. Percy Julian had so many personal and professional obstacles throughout his life, it’s amazing he was able to accomplish anything at all. But this hidden figure not only overcame these incredible obstacles, he also laid the foundation for the creation of the birth control pill.

Julian’s first obstacle was growing up in the Jim Crow-era south in the early part of the twentieth century, where racial segregation kept many African-Americans out of schools, libraries, parks, restaurants, and more. Despite limited opportunities and education, Julian was accepted to DePauw University in Indiana, where he majored in chemistry. But in college, Julian encountered another obstacle: he wasn’t allowed to stay in DePauw’s student housing because of segregation. Julian found lodging in an off-campus boarding house that refused to serve him meals. To pay for his room, board, and food, Julian waited tables and fired furnaces while he studied chemistry full-time. Incredibly, he graduated in 1920 as valedictorian of his class.

After graduation, Julian landed a fellowship at Harvard University to study chemistry—but here, Julian ran into yet another obstacle. Harvard thought that white students would resent being taught by Julian, an African-American man, so they withdrew his teaching assistantship. Julian instead decided to complete his PhD at the University of Vienna in Austria. When he did, he became one of the first African Americans to ever receive a PhD in chemistry.

Julian received offers for professorships, fellowships, and jobs throughout the 1930s, due to his impressive qualifications—but these offers were almost always revoked when schools or potential employers found out Julian was black. In one instance, Julian was offered a job at the Institute of Paper Chemistory in Appleton, Wisconsin—but Appleton, like many cities in the United States at the time, was known as a “sundown town,” which meant that black people weren’t allowed to be there after dark. As a result, Julian lost the job.

During this time, Julian became an expert at synthesis, which is the process of turning one substance into another through a series of planned chemical reactions. Julian synthesized a plant compound called physostigmine, which would later become a treatment for an eye disease called glaucoma.

In 1936, Julian was finally able to land—and keep—a job at Glidden, and there he found a way to extract soybean protein. This was used to produce a fire-retardant foam used in fire extinguishers to smother oil and gasoline fires aboard ships and aircraft carriers, and it ended up saving the lives of thousands of soldiers during World War II.

At Glidden, Julian found a way to synthesize human sex hormones such as progesterone, estrogen, and testosterone, from plants. This was a hugely profitable discovery for his company—but it also meant that clinicians now had huge quantities of these hormones, making hormone therapy cheaper and easier to come by. His work also laid the foundation for the creation of hormonal birth control: Without the ability to synthesize these hormones, hormonal birth control would not exist.

Julian left Glidden in the 1950s and formed his own company, called Julian Laboratories, outside of Chicago, where he manufactured steroids and conducted his own research. The company turned profitable within a year, but even so Julian’s obstacles weren’t over. In 1950 and 1951, Julian’s home was firebombed and attacked with dynamite, with his family inside. Julian often had to sit out on the front porch of his home with a shotgun to protect his family from violence.

But despite years of racism and violence, Julian’s story has a happy ending. Julian’s family was eventually welcomed into the neighborhood and protected from future attacks (Julian’s daughter lives there to this day). Julian then became one of the country’s first black millionaires when he sold his company in the 1960s.

When Julian passed away at the age of 76, he had more than 130 chemical patents to his name and left behind a body of work that benefits people to this day.

Therapies for Healthy Aging with Dr. Alexandra Bause

My guest today is Dr. Alexandra Bause, a biologist who has dedicated her career to advancing health, medicine and healthier human lifespans. Dr. Bause co-founded a company called Apollo Health Ventures in 2017. Currently a venture partner at Apollo, she's immersed in the discoveries underway in Apollo’s Venture Lab while the company focuses on assembling a team of investors to support progress. Dr. Bause and Apollo Health Ventures say that biotech is at “an inflection point” and is set to become a driver of important change and economic value.

Previously, Dr. Bause worked at the Boston Consulting Group in its healthcare practice specializing in biopharma strategy, among other priorities

She did her PhD studies at Harvard Medical School focusing on molecular mechanisms that contribute to cellular aging, and she’s also a trained pharmacist

In the episode, we talk about the present and future of therapeutics that could increase people’s spans of health, the benefits of certain lifestyle practice, the best use of electronic wearables for these purposes, and much more.

Dr. Bause is at the forefront of developing interventions that target the aging process with the aim of ensuring that all of us can have healthier, more productive lifespans.