Can blockchain help solve the Henrietta Lacks problem?

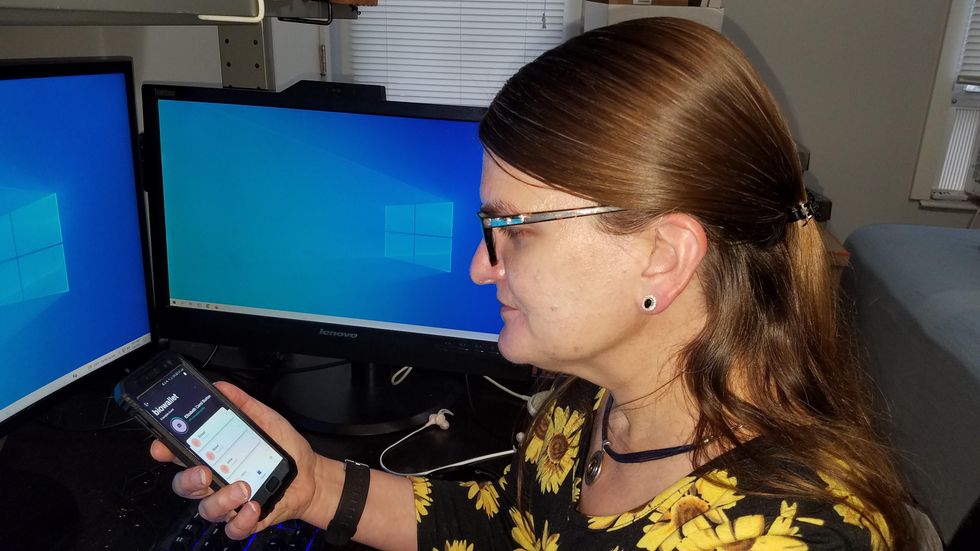

Marielle Gross, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, shows patients a new app that tracks how their samples are used during biomedical research.

Science has come a long way since Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman from Baltimore, succumbed to cervical cancer at age 31 in 1951 -- only eight months after her diagnosis. Since then, research involving her cancer cells has advanced scientific understanding of the human papilloma virus, polio vaccines, medications for HIV/AIDS and in vitro fertilization.

Today, the World Health Organization reports that those cells are essential in mounting a COVID-19 response. But they were commercialized without the awareness or permission of Lacks or her family, who have filed a lawsuit against a biotech company for profiting from these “HeLa” cells.

While obtaining an individual's informed consent has become standard procedure before the use of tissues in medical research, many patients still don’t know what happens to their samples. Now, a new phone-based app is aiming to change that.

Tissue donors can track what scientists do with their samples while safeguarding privacy, through a pilot program initiated in October by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics and the University of Pittsburgh’s Institute for Precision Medicine. The program uses blockchain technology to offer patients this opportunity through the University of Pittsburgh's Breast Disease Research Repository, while assuring that their identities remain anonymous to investigators.

A blockchain is a digital, tamper-proof ledger of transactions duplicated and distributed across a computer system network. Whenever a transaction occurs with a patient’s sample, multiple stakeholders can track it while the owner’s identity remains encrypted. Special certificates called “nonfungible tokens,” or NFTs, represent patients’ unique samples on a trusted and widely used blockchain that reinforces transparency.

Blockchain could be used to notify people if cancer researchers discover that they have certain risk factors.

“Healthcare is very data rich, but control of that data often does not lie with the patient,” said Julius Bogdan, vice president of analytics for North America at the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), a Chicago-based global technology nonprofit. “NFTs allow for the encapsulation of a patient’s data in a digital asset controlled by the patient.” He added that this technology enables a more secure and informed method of participating in clinical and research trials.

Without this technology, de-identification of patients’ samples during biomedical research had the unintended consequence of preventing them from discovering what researchers find -- even if that data could benefit their health. A solution was urgently needed, said Marielle Gross, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive science and bioethics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

“A researcher can learn something from your bio samples or medical records that could be life-saving information for you, and they have no way to let you or your doctor know,” said Gross, who is also an affiliate assistant professor at the Berman Institute. “There’s no good reason for that to stay the way that it is.”

For instance, blockchain could be used to notify people if cancer researchers discover that they have certain risk factors. Gross estimated that less than half of breast cancer patients are tested for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 — tumor suppressor genes that are important in combating cancer. With normal function, these genes help prevent breast, ovarian and other cells from proliferating in an uncontrolled manner. If researchers find mutations, it’s relevant for a patient’s and family’s follow-up care — and that’s a prime example of how this newly designed app could play a life-saving role, she said.

Liz Burton was one of the first patients at the University of Pittsburgh to opt for the app -- called de-bi, which is short for decentralized biobank -- before undergoing a mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer in November, after it was diagnosed on a routine mammogram. She often takes part in medical research and looks forward to tracking her tissues.

“Anytime there’s a scientific experiment or study, I’m quick to participate -- to advance my own wellness as well as knowledge in general,” said Burton, 49, a life insurance service representative who lives in Carnegie, Pa. “It’s my way of contributing.”

Liz Burton was one of the first patients at the University of Pittsburgh to opt for the app before undergoing a mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer.

Liz Burton

The pilot program raises the issue of what investigators may owe study participants, especially since certain populations, such as Black and indigenous peoples, historically were not treated in an ethical manner for scientific purposes. “It’s a truly laudable effort,” Tamar Schiff, a postdoctoral fellow in medical ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, said of the endeavor. “Research participants are beautifully altruistic.”

Lauren Sankary, a bioethicist and associate director of the neuroethics program at Cleveland Clinic, agrees that the pilot program provides increased transparency for study participants regarding how scientists use their tissues while acknowledging individuals’ contributions to research.

However, she added, “it may require researchers to develop a process for ongoing communication to be responsive to additional input from research participants.”

Peter H. Schwartz, professor of medicine and director of Indiana University’s Center for Bioethics in Indianapolis, said the program is promising, but he wonders what will happen if a patient has concerns about a particular research project involving their tissues.

“I can imagine a situation where a patient objects to their sample being used for some disease they’ve never heard about, or which carries some kind of stigma like a mental illness,” Schwartz said, noting that researchers would have to evaluate how to react. “There’s no simple answer to those questions, but the technology has to be assessed with an eye to the problems it could raise.”

To truly make a difference, blockchain must enable broad consent from patients, not just de-identification.

As a result, researchers may need to factor in how much information to share with patients and how to explain it, Schiff said. There are also concerns that in tracking their samples, patients could tell others what they learned before researchers are ready to publicly release this information. However, Bogdan, the vice president of the HIMSS nonprofit, believes only a minimal study identifier would be stored in an NFT, not patient data, research results or any type of proprietary trial information.

Some patients may be confused by blockchain and reluctant to embrace it. “The complexity of NFTs may prevent the average citizen from capitalizing on their potential or vendors willing to participate in the blockchain network,” Bogdan said. “Blockchain technology is also quite costly in terms of computational power and energy consumption, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.”

In addition, this nascent, groundbreaking technology is immature and vulnerable to data security flaws, disputes over intellectual property rights and privacy issues, though it does offer baseline protections to maintain confidentiality. To truly make a difference, blockchain must enable broad consent from patients, not just de-identification, said Robyn Shapiro, a bioethicist and founding attorney at Health Sciences Law Group near Milwaukee.

The Henrietta Lacks story is a prime example, Shapiro noted. During her treatment for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins, Lacks’s tissue was de-identified (albeit not entirely, because her cell line, HeLa, bore her initials). After her death, those cells were replicated and distributed for important and lucrative research and product development purposes without her knowledge or consent.

Nonetheless, Shapiro thinks that the initiative by the University of Pittsburgh and Johns Hopkins has potential to solve some ethical challenges involved in research use of biospecimens. “Compared to the system that allowed Lacks’s cells to be used without her permission, Shapiro said, “blockchain technology using nonfungible tokens that allow patients to follow their samples may enhance transparency, accountability and respect for persons who contribute their tissue and clinical data for research.”

Read more about laws that have prevented people from the rights to their own cells.

A company has slashed the cost of assessing a person's genome to just $100. With lower costs - and as other genetic tools mature and evolve - a wave of new therapies could be coming in the near future.

In May 2022, Californian biotech Ultima Genomics announced that its UG 100 platform was capable of sequencing an entire human genome for just $100, a landmark moment in the history of the field. The announcement was particularly remarkable because few had previously heard of the company, a relative unknown in an industry long dominated by global giant Illumina which controls about 80 percent of the world’s sequencing market.

Ultima’s secret was to completely revamp many technical aspects of the way Illumina have traditionally deciphered DNA. The process usually involves first splitting the double helix DNA structure into single strands, then breaking these strands into short fragments which are laid out on a glass surface called a flow cell. When this flow cell is loaded into the sequencing machine, color-coded tags are attached to each individual base letter. A laser scans the bases individually while a camera simultaneously records the color associated with them, a process which is repeated until every single fragment has been sequenced.

Instead, Ultima has found a series of shortcuts to slash the cost and boost efficiency. “Ultima Genomics has developed a fundamentally new sequencing architecture designed to scale beyond conventional approaches,” says Josh Lauer, Ultima’s chief commercial officer.

This ‘new architecture’ is a series of subtle but highly impactful tweaks to the sequencing process ranging from replacing the costly flow cell with a silicon wafer which is both cheaper and allows more DNA to be read at once, to utilizing machine learning to convert optical data into usable information.

To put $100 genome in perspective, back in 2012 the cost of sequencing a single genome was around $10,000, a price tag which dropped to $1,000 a few years later. Before Ultima’s announcement, the cost of sequencing an individual genome was around $600.

Several studies have found that nearly 12 percent of healthy people who have their genome sequenced, then discover they have a variant pointing to a heightened risk of developing a disease that can be monitored, treated or prevented.

While Ultima’s new machine is not widely available yet, Illumina’s response has been rapid. Last month the company unveiled the NovaSeq X series, which it describes as its fastest most cost-efficient sequencing platform yet, capable of sequencing genomes at $200, with further price cuts likely to follow.

But what will the rapidly tumbling cost of sequencing actually mean for medicine? “Well to start with, obviously it’s going to mean more people getting their genome sequenced,” says Michael Snyder, professor of genetics at Stanford University. “It'll be a lot more accessible to people.”

At the moment sequencing is mainly limited to certain cancer patients where it is used to inform treatment options, and individuals with undiagnosed illnesses. In the past, initiatives such as SeqFirst have attempted further widen access to genome sequencing based on growing amounts of research illustrating the potential benefits of the technology in healthcare. Several studies have found that nearly 12 percent of healthy people who have their genome sequenced, then discover they have a variant pointing to a heightened risk of developing a disease that can be monitored, treated or prevented.

“While whole genome sequencing is not yet widely used in the U.S., it has started to come into pediatric critical care settings such as newborn intensive care units,” says Professor Michael Bamshad, who heads the genetic medicine division in the University of Washington’s pediatrics department. “It is also being used more often in outpatient clinical genetics services, particularly when conventional testing fails to identify explanatory variants.”

But the cost of sequencing itself is only one part of the price tag. The subsequent clinical interpretation and genetic counselling services often come to several thousand dollars, a cost which insurers are not always willing to pay.

As a result, while Bamshad and others hope that the arrival of the $100 genome will create new opportunities to use genetic testing in innovative ways, the most immediate benefits are likely to come in the realm of research.

Bigger Data

There are numerous ways in which cheaper sequencing is likely to advance scientific research, for example the ability to collect data on much larger patient groups. This will be a major boon to scientists working on complex heterogeneous diseases such as schizophrenia or depression where there are many genes involved which all exert subtle effects, as well as substantial variance across the patient population. Bigger studies could help scientists identify subgroups of patients where the disease appears to be driven by similar gene variants, who can then be more precisely targeted with specific drugs.

If insurers can figure out the economics, Snyder even foresees a future where at a certain age, all of us can qualify for annual sequencing of our blood cells to search for early signs of cancer or the potential onset of other diseases like type 2 diabetes.

David Curtis, a genetics professor at University College London, says that scientists studying these illnesses have previously been forced to rely on genome-wide association studies which are limited because they only identify common gene variants. “We might see a significant increase in the number of large association studies using sequence data,” he says. “It would be far preferable to use this because it provides information about rare, potentially functional variants.”

Cheaper sequencing will also aid researchers working on diseases which have traditionally been underfunded. Bamshad cites cystic fibrosis, a condition which affects around 40,000 children and adults in the U.S., as one particularly pertinent example.

“Funds for gene discovery for rare diseases are very limited,” he says. “We’re one of three sites that did whole genome sequencing on 5,500 people with cystic fibrosis, but our statistical power is limited. A $100 genome would make it much more feasible to sequence everyone in the U.S. with cystic fibrosis and make it more likely that we discover novel risk factors and pathways influencing clinical outcomes.”

For progressive diseases that are more common like cancer and type 2 diabetes, as well as neurodegenerative conditions like multiple sclerosis and ALS, geneticists will be able to go even further and afford to sequence individual tumor cells or neurons at different time points. This will enable them to analyze how individual DNA modifications like methylation, change as the disease develops.

In the case of cancer, this could help scientists understand how tumors evolve to evade treatments. Within in a clinical setting, the ability to sequence not just one, but many different cells across a patient’s tumor could point to the combination of treatments which offer the best chance of eradicating the entire cancer.

“What happens at the moment with a solid tumor is you treat with one drug, and maybe 80 percent of that tumor is susceptible to that drug,” says Neil Ward, vice president and general manager in the EMEA region for genomics company PacBio. “But the other 20 percent of the tumor has already got mutations that make it resistant, which is probably why a lot of modern therapies extend life for sadly only a matter of months rather than curing, because they treat a big percentage of the tumor, but not the whole thing. So going forwards, I think that we will see genomics play a huge role in cancer treatments, through using multiple modalities to treat someone's cancer.”

If insurers can figure out the economics, Snyder even foresees a future where at a certain age, all of us can qualify for annual sequencing of our blood cells to search for early signs of cancer or the potential onset of other diseases like type 2 diabetes.

“There are companies already working on looking for cancer signatures in methylated DNA,” he says. “If it was determined that you had early stage cancer, pre-symptomatically, that could then be validated with targeted MRI, followed by surgery or chemotherapy. It makes a big difference catching cancer early. If there were signs of type 2 diabetes, you could start taking steps to mitigate your glucose rise, and possibly prevent it or at least delay the onset.”

This would already revolutionize the way we seek to prevent a whole range of illnesses, but others feel that the $100 genome could also usher in even more powerful and controversial preventative medicine schemes.

Newborn screening

In the eyes of Kári Stefánsson, the Icelandic neurologist who been a visionary for so many advances in the field of human genetics over the last 25 years, the falling cost of sequencing means it will be feasible to sequence the genomes of every baby born.

“We have recently done an analysis of genomes in Iceland and the UK Biobank, and in 4 percent of people you find mutations that lead to serious disease, that can be prevented or dealt with,” says Stefansson, CEO of deCODE genetics, a subsidiary of the pharmaceutical company Amgen. “This could transform our healthcare systems.”

As well as identifying newborns with rare diseases, this kind of genomic information could be used to compute a person’s risk score for developing chronic illnesses later in life. If for example, they have a higher than average risk of colon or breast cancer, they could be pre-emptively scheduled for annual colonoscopies or mammograms as soon as they hit adulthood.

To a limited extent, this is already happening. In the UK, Genomics England has launched the Newborn Genomes Programme, which plans to undertake whole-genome sequencing of up to 200,000 newborn babies, with the aim of enabling the early identification of rare genetic diseases.

"I have not had my own genome sequenced and I would not have wanted my parents to have agreed to this," Curtis says. "I don’t see that sequencing children for the sake of some vague, ill-defined benefits could ever be justifiable.”

However, some scientists feel that it is tricky to justify sequencing the genomes of apparently healthy babies, given the data privacy issues involved. They point out that we still know too little about the links which can be drawn between genetic information at birth, and risk of chronic illness later in life.

“I think there are very difficult ethical issues involved in sequencing children if there are no clear and immediate clinical benefits,” says Curtis. “They cannot consent to this process. I have not had my own genome sequenced and I would not have wanted my parents to have agreed to this. I don’t see that sequencing children for the sake of some vague, ill-defined benefits could ever be justifiable.”

Curtis points out that there are many inherent risks about this data being available. It may fall into the hands of insurance companies, and it could even be used by governments for surveillance purposes.

“Genetic sequence data is very useful indeed for forensic purposes. Its full potential has yet to be realized but identifying rare variants could provide a quick and easy way to find relatives of a perpetrator,” he says. “If large numbers of people had been sequenced in a healthcare system then it could be difficult for a future government to resist the temptation to use this as a resource to investigate serious crimes.”

While sequencing becoming more widely available will present difficult ethical and moral challenges, it will offer many benefits for society as a whole. Cheaper sequencing will help boost the diversity of genomic datasets which have traditionally been skewed towards individuals of white, European descent, meaning that much of the actionable medical information which has come out of these studies is not relevant to people of other ethnicities.

Ward predicts that in the coming years, the growing amount of genetic information will ultimately change the outcomes for many with rare, previously incurable illnesses.

“If you're the parent of a child that has a susceptible or a suspected rare genetic disease, their genome will get sequenced, and while sadly that doesn’t always lead to treatments, it’s building up a knowledge base so companies can spring up and target that niche of a disease,” he says. “As a result there’s a whole tidal wave of new therapies that are going to come to market over the next five years, as the genetic tools we have, mature and evolve.”

In this week's Friday Five, an old diabetes drug finds an exciting new purpose. Plus, how to make the cities of the future less toxic, making old mice younger with EVs, a new reason for mysterious stillbirths - and much more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here is the promising research covered in this week's Friday Five:

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

- How to make cities of the future less noisy

- An old diabetes drug could have a new purpose: treating an irregular heartbeat

- A new reason for mysterious stillbirths

- Making old mice younger with EVs

- No pain - or mucus - no gain

And an honorable mention this week: How treatments for depression can change the structure of the brain