Blood Money: Paying for Convalescent Plasma to Treat COVID-19

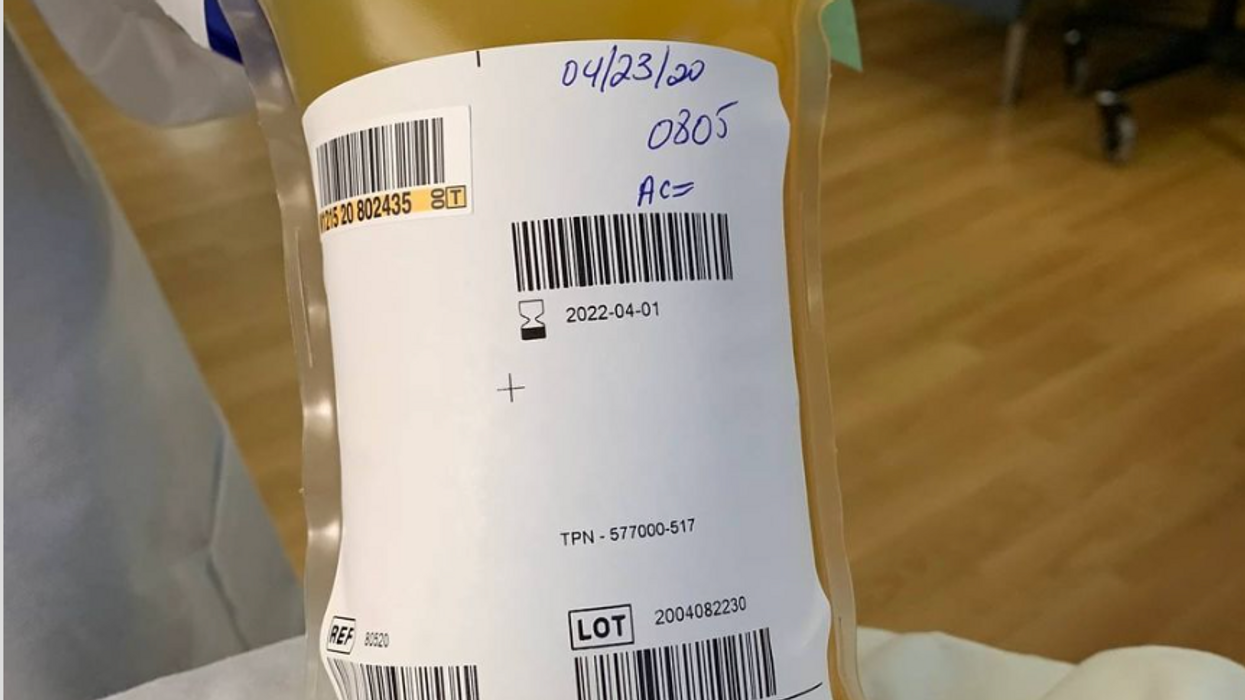

A bag of plasma that Tom Hanks donated back in April 2020 after his coronavirus infection. (He was not paid to donate.)

Convalescent plasma – first used to treat diphtheria in 1890 – has been dusted off the shelf to treat COVID-19. Does it work? Should we rely strictly on the altruism of donors or should people be paid for it?

The biologic theory is that a person who has recovered from a disease has chemicals in their blood, most likely antibodies, that contributed to their recovery, and transferring those to a person who is sick might aid their recovery. Whole blood won't work because there are too few antibodies in a single unit of blood and the body can hold only so much of it.

Plasma comprises about 55 percent of whole blood and is what's left once you take out the red blood cells that carry oxygen and the white blood cells of the immune system. Most of it is water but the rest is a complex mix of fats, salts, signaling molecules and proteins produced by the immune system, including antibodies.

A process called apheresis circulates the donors' blood through a machine that separates out the desired parts of blood and returns the rest to the donor. It takes several times the length of a regular whole blood donation to cycle through enough blood for the process. The end product is a yellowish concentration called convalescent plasma.

Recent History

It was used extensively during the great influenza epidemic off 1918 but fell out of favor with the development of antibiotics. Still, whenever a new disease emerges – SARS, MERS, Ebola, even antibiotic-resistant bacteria – doctors turn to convalescent plasma, often as a stopgap until more effective antibiotic and antiviral drugs are developed. The process is certainly safe when standard procedures for handling blood products are followed, and historically it does seem to be beneficial in at least some patients if administered early enough in the disease.

With few good treatment options for COVID-19, doctors have given convalescent plasma to more than a hundred thousand Americans and tens of thousand of people elsewhere, to mixed results. Placebo-controlled trials could give a clearer picture of plasma's value but it is difficult to enroll patients facing possible death when the flip of a coin will determine who will receive a saline solution or plasma.

And the plasma itself isn't some uniform pill stamped out in a factory, it's a natural product that is shaped by the immune history of the donor's body and its encounter not just with SARS-CoV-2 but a lifetime of exposure to different pathogens.

Researchers believe antibodies in plasma are a key factor in directly fighting the virus. But the variety and quantity of antibodies vary from donor to donor, and even over time from the same donor because once the immune system has cleared the virus from the body, it stops putting out antibodies to fight the virus. Often the quality and quantity of antibodies being given to a patient are not measured, making it somewhat hit or miss, which is why several companies have recently developed monoclonal antibodies, a single type of antibody found in blood that is effective against SARS-CoV-2 and that is multiplied in the lab for use as therapy.

Plasma may also contain other unknown factors that contribute to fighting disease, say perhaps signaling molecules that affect gene expression, which might affect the movement of immune cells, their production of antiviral molecules, or the regulation of inflammation. The complexity and lack of standardization makes it difficult to evaluate what might be working or not with a convalescent plasma treatment. Thus researchers are left with few clues about how to make it more effective.

Industrializing Plasma

Many Americans living along the border with Mexico regularly head south to purchase prescription drugs at a significant discount. Less known is the medical traffic the other way, Mexicans who regularly head north to be paid for plasma donations, which are prohibited in their country; the U.S. allows payment for plasma donations but not whole blood. A typical payment is about $35 for a donation but the sudden demand for convalescent plasma from people who have recovered from COVID-19 commands a premium price, sometimes as high as $200. These donors are part of a fast-growing plasma industry that surpassed $25 billion in 2018. The U.S. supplies about three-quarters of the world's needs for plasma.

Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free.

The pharmaceutical industry has shied away from natural products they cannot patent but they have identified simpler components from plasma, such as clotting factors and immunoglobulins, that have been turned into useful drugs from this raw material of plasma. While some companies have retooled to provide convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19, often paying those donors who have recovered a premium of several times the normal rate, most convalescent plasma has come as donations through traditional blood centers.

In April the Mayo Clinic, in cooperation with the FDA, created an expanded access program for convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19. It was meant to reduce the paperwork associated with gaining access to a treatment not yet approved by the FDA for that disease. Initially it was supposed to be for 5000 units but it quickly grew to more than twenty times that size. Michael Joyner, the head of the program, discussed that experience in an extended interview in September.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also created associated reimbursement codes, which became permanent in August.

Mayo published an analysis of the first 35,000 patients as a preprint in August. It concluded, "The relationships between mortality and both time to plasma transfusion, and antibody levels provide a signature that is consistent with efficacy for the use of convalescent plasma in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients."

It seemed to work best when given early in infection and in larger doses; a similar pattern has been seen in studies of monoclonal antibodies. A revised version will soon be published in a major medical journal. Some criticized the findings as not being from a randomized clinical trial.

Convalescent plasma is not the only intervention that seems to work better when used earlier in the course of disease. Recently the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly stopped a clinical trial of a monoclonal antibody in hospitalized COVID-19 patients when it became apparent it wasn't helping. It is continuing trials for patients who are less sick and begin treatment earlier, as well as in persons who have been exposed to the virus but not yet diagnosed as infected, to see if it might prevent infection. In November the FDA eased access to this drug outside of clinical trials, though it is not yet approved for sale.

Show Me the Money

The antibodies that seem to give plasma its curative powers are fragile proteins that the body produces to fight the virus. Production shuts down once the virus is cleared and the remaining antibodies survive only for a few weeks before the levels fade. [Vaccines are used to train immune cells to produce antibodies and other defenses to respond to exposure to future pathogens.] So they can be usefully harvested from a recovered patient for only a few short weeks or months before they decline precipitously. The question becomes, how does one mobilize this resource in that short window of opportunity?

The program run by the Mayo Clinic explains the process and criteria for donating convalescent plasma for COVID-19, as well as links to local blood centers equipped to handle those free donations. Commercial plasma centers also are advertising and paying for donations.

A majority of countries prohibit paying donors for blood or blood products, including India. But an investigation by India Today touted a black market of people willing to donate convalescent plasma for the equivalent of several hundred dollars. Officials vowed to prosecute, saying donations should be selfless.

But that enforcement threat seemed to be undercut when the health minister of the state of Assam declared "plasma donors will get preference in several government schemes including the government job interview." It appeared to be a form of compensation that far surpassed simple cash.

The small city of Rexburg, Idaho, with a population a bit over 50,000, overwhelmingly Mormon and home to a campus of Brigham Young University, at one point had one of the highest per capita rates of COVID-19 in the current wave of infection. Rumors circulated that some students were intentionally trying to become infected so they could later sell their plasma for top dollar, potentially as much as $200 a visit.

Troubled university officials investigated the allegations but could come up with nothing definitive; how does one prove intentionality with such an omnipresent yet elusive virus? They chalked it up to idle chatter, perhaps an urban legend, which might be associated with alcohol use on some other campus.

Doctors, hospitals, and drug companies are all rightly praised for their altruism in the fight against COVID-19, but they also get paid. Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free. "Why do we expect the donors [of convalescent plasma] to be the only uncompensated people in the process? It really makes no sense," argues Mark Yarborough, an ethicist at the UC Davis School of Medicine in Sacramento.

"When I was in grad school, two of my closest friends, at least once a week they went and gave plasma. That was their weekend spending money," Yarborough recalls. He says upper and middle-income people may have the luxury of donating blood products but prohibiting people from selling their plasma is a bit paternalistic and doesn't do anything to improve the economic status of poor people.

"Asking people to dedicate two hours a week for an entire year in exchange for cookies and milk is demonstrably asking too much," says Peter Jaworski, an ethicist who teaches at Georgetown University.

He notes that companies that pay plasma donors have much lower total costs than do operations that rely solely on uncompensated donations. The companies have to spend less to recruit and retain donors because they increase payments to encourage regular repeat donations. They are able to more rationally schedule visits to maximize use of expensive apheresis equipment and medical personnel used for the collection.

It seems that COVID-19 has been with us forever, but in reality it is less than a year. We have learned much over that short time, can now better manage the disease, and have lower mortality rates to prove it. Just how much convalescent plasma may have contributed to that remains an open question. Access to vaccines is months away for many people, and even then some people will continue to get sick. Given the lack of proven treatments, it makes sense to keep plasma as part of the mix, and not close the door to any legitimate means to obtain it.

Meet Dr. Renee Wegrzyn, the first Director of President Biden's new health agency, ARPA-H

Today's podcast guest, Dr. Renee Wegrzyn, directs ARPA-H, a new agency formed last year to spearhead health innovations. Time will tell if ARPA-H will produce advances on the level of its fellow agency, DARPA.

In today’s podcast episode, I talk with Renee Wegrzyn, appointed by President Biden as the first director of a health agency created last year, the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, or ARPA-H. It’s inspired by DARPA, the agency that develops innovations for the Defense department and has been credited with hatching world-changing technologies such as ARPANET, which became the internet.

Time will tell if ARPA-H will lead to similar achievements in the realm of health. That’s what President Biden and Congress expect in return for funding ARPA-H at 2.5 billion dollars over three years.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

How will the agency figure out which projects to take on, especially with so many patient advocates for different diseases demanding moonshot funding for rapid progress?

I talked with Dr. Wegrzyn about the opportunities and challenges, what lessons ARPA-H is borrowing from Operation Warp Speed, how she decided on the first ARPA-H project that was announced recently, why a separate agency was needed instead of reforming HHS and the National Institutes of Health to be better at innovation, and how ARPA-H will make progress on disease prevention in addition to treatments for cancer, Alzheimer’s and diabetes, among many other health priorities.

Dr. Wegrzyn’s resume leaves no doubt of her suitability for this role. She was a program manager at DARPA where she focused on applying gene editing and synthetic biology to the goal of improving biosecurity. For her work there, she received the Superior Public Service Medal and, in case that wasn’t enough ARPA experience, she also worked at another ARPA that leads advanced projects in intelligence, called I-ARPA. Before that, she ran technical teams in the private sector working on gene therapies and disease diagnostics, among other areas. She has been a vice president of business development at Gingko Bioworks and headed innovation at Concentric by Gingko. Her training and education includes a PhD and undergraduate degree in applied biology from the Georgia Institute of Technology and she did her postdoc as an Alexander von Humboldt Fellow in Heidelberg, Germany.

Dr. Wegrzyn told me that she’s “in the hot seat.” The pressure is on for ARPA-H especially after the need and potential for health innovation was spot lit by the pandemic and the unprecedented speed of vaccine development. We'll soon find out if ARPA-H can produce gamechangers in health that are equivalent to DARPA’s creation of the internet.

Show links:

ARPA-H - https://arpa-h.gov/

Dr. Wegrzyn profile - https://arpa-h.gov/people/renee-wegrzyn/

Dr. Wegrzyn Twitter - https://twitter.com/rwegrzyn?lang=en

President Biden Announces Dr. Wegrzyn's appointment - https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statement...

Leaps.org coverage of ARPA-H - https://leaps.org/arpa/

ARPA-H program for joints to heal themselves - https://arpa-h.gov/news/nitro/ -

ARPA-H virtual talent search - https://arpa-h.gov/news/aco-talent-search/

Dr. Renee Wegrzyn was appointed director of ARPA-H last October.

Tiny, tough “water bears” may help bring new vaccines and medicines to sub-Saharan Africa

Tardigrades can completely dehydrate and later rehydrate themselves, a survival trick that scientists are harnessing to preserve medicines in hot temperatures.

Microscopic tardigrades, widely considered to be some of the toughest animals on earth, can survive for decades without oxygen or water and are thought to have lived through a crash-landing on the moon. Also known as water bears, they survive by fully dehydrating and later rehydrating themselves – a feat only a few animals can accomplish. Now scientists are harnessing tardigrades’ talents to make medicines that can be dried and stored at ambient temperatures and later rehydrated for use—instead of being kept refrigerated or frozen.

Many biologics—pharmaceutical products made by using living cells or synthesized from biological sources—require refrigeration, which isn’t always available in many remote locales or places with unreliable electricity. These products include mRNA and other vaccines, monoclonal antibodies and immuno-therapies for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and other conditions. Cooling is also needed for medicines for blood clotting disorders like hemophilia and for trauma patients.

Formulating biologics to withstand drying and hot temperatures has been the holy grail for pharmaceutical researchers for decades. It’s a hard feat to manage. “Biologic pharmaceuticals are highly efficacious, but many are inherently unstable,” says Thomas Boothby, assistant professor of molecular biology at University of Wyoming. Therefore, during storage and shipping, they must be refrigerated at 2 to 8 degrees Celsius (35 to 46 degrees Fahrenheit). Some must be frozen, typically at -20 degrees Celsius, but sometimes as low -90 degrees Celsius as was the case with the Pfizer Covid vaccine.

For Covid, fewer than 73 percent of the global population received even one dose. The need for refrigerated or frozen handling was partially to blame.

The costly cold chain

The logistics network that ensures those temperature requirements are met from production to administration is called the cold chain. This cold chain network is often unreliable or entirely lacking in remote, rural areas in developing nations that have malfunctioning electrical grids. “Almost all routine vaccines require a cold chain,” says Christopher Fox, senior vice president of formulations at the Access to Advanced Health Institute. But when the power goes out, so does refrigeration, putting refrigerated or frozen medical products at risk. Consequently, the mRNA vaccines developed for Covid-19 and other conditions, as well as more traditional vaccines for cholera, tetanus and other diseases, often can’t be delivered to the most remote parts of the world.

To understand the scope of the challenge, consider this: In the U.S., more than 984 million doses of Covid-19 vaccine have been distributed so far. Each one needed refrigeration that, even in the U.S., proved challenging. Now extrapolate to all vaccines and the entire world. For Covid, fewer than 73 percent of the global population received even one dose. The need for refrigerated or frozen handling was partially to blame.

Globally, the cold chain packaging market is valued at over $15 billion and is expected to exceed $60 billion by 2033.

Adobe Stock

Freeze-drying, also called lyophilization, which is common for many vaccines, isn’t always an option. Many freeze-dried vaccines still need refrigeration, and even medicines approved for storage at ambient temperatures break down in the heat of sub-Saharan Africa. “Even in a freeze-dried state, biologics often will undergo partial rehydration and dehydration, which can be extremely damaging,” Boothby explains.

The cold chain is also very expensive to maintain. The global pharmaceutical cold chain packaging market is valued at more than $15 billion, and is expected to exceed $60 billion by 2033, according to a report by Future Market Insights. This cost is only expected to grow. According to the consulting company Accenture, the number of medicines that require the cold chain are expected to grow by 48 percent, compared to only 21 percent for non-cold-chain therapies.

Tardigrades to the rescue

Tardigrades are only about a millimeter long – with four legs and claws, and they lumber around like bears, thus their nickname – but could provide a big solution. “Tardigrades are unique in the animal kingdom, in that they’re able to survive a vast array of environmental insults,” says Boothby, the Wyoming professor. “They can be dried out, frozen, heated past the boiling point of water and irradiated at levels that are thousands of times more than you or I could survive.” So, his team is gradually unlocking tardigrades’ survival secrets and applying them to biologic pharmaceuticals to make them withstand both extreme heat and desiccation without losing efficacy.

Boothby’s team is focusing on blood clotting factor VIII, which, as the name implies, causes blood to clot. Currently, Boothby is concentrating on the so-called cytoplasmic abundant heat soluble (CAHS) protein family, which is found only in tardigrades, protecting them when they dry out. “We showed we can desiccate a biologic (blood clotting factor VIII, a key clotting component) in the presence of tardigrade proteins,” he says—without losing any of its effectiveness.

The researchers mixed the tardigrade protein with the blood clotting factor and then dried and rehydrated that substance six times without damaging the latter. This suggests that biologics protected with tardigrade proteins can withstand real-world fluctuations in humidity.

Furthermore, Boothby’s team found that when the blood clotting factor was dried and stabilized with tardigrade proteins, it retained its efficacy at temperatures as high as 95 degrees Celsius. That’s over 200 degrees Fahrenheit, much hotter than the 58 degrees Celsius that the World Meteorological Organization lists as the hottest recorded air temperature on earth. In contrast, without the protein, the blood clotting factor degraded significantly. The team published their findings in the journal Nature in March.

Although tardigrades rarely live more than 2.5 years, they have survived in a desiccated state for up to two decades, according to Animal Diversity Web. This suggests that tardigrades’ CAHS protein can protect biologic pharmaceuticals nearly indefinitely without refrigeration or freezing, which makes it significantly easier to deliver them in locations where refrigeration is unreliable or doesn’t exist.

The tricks of the tardigrades

Besides the CAHS proteins, tardigrades rely on a type of sugar called trehalose and some other protectants. So, rather than drying up, their cells solidify into rigid, glass-like structures. As that happens, viscosity between cells increases, thereby slowing their biological functions so much that they all but stop.

Now Boothby is combining CAHS D, one of the proteins in the CAHS family, with trehalose. He found that CAHS D and trehalose each protected proteins through repeated drying and rehydrating cycles. They also work synergistically, which means that together they might stabilize biologics under a variety of dry storage conditions.

“We’re finding the protective effect is not just additive but actually is synergistic,” he says. “We’re keen to see if something like that also holds true with different protein combinations.” If so, combinations could possibly protect against a variety of conditions.

Commercialization outlook

Before any stabilization technology for biologics can be commercialized, it first must be approved by the appropriate regulators. In the U.S., that’s the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Developing a new formulation would require clinical testing and vast numbers of participants. So existing vaccines and biologics likely won’t be re-formulated for dry storage. “Many were developed decades ago,” says Fox. “They‘re not going to be reformulated into thermo-stable vaccines overnight,” if ever, he predicts.

Extending stability outside the cold chain, even for a few days, can have profound health, environmental and economic benefits.

Instead, this technology is most likely to be used for the new products and formulations that are just being created. New and improved vaccines will be the first to benefit. Good candidates include the plethora of mRNA vaccines, as well as biologic pharmaceuticals for neglected diseases that affect parts of the world where reliable cold chain is difficult to maintain, Boothby says. Some examples include new, more effective vaccines for malaria and for pathogenic Escherichia coli, which causes diarrhea.

Tallying up the benefits

Extending stability outside the cold chain, even for a few days, can have profound health, environmental and economic benefits. For instance, MenAfriVac, a meningitis vaccine (without tardigrade proteins) developed for sub-Saharan Africa, can be stored at up to 40 degrees Celsius for four days before administration. “If you have a few days where you don’t need to maintain the cold chain, it’s easier to transport vaccines to remote areas,” Fox says, where refrigeration does not exist or is not reliable.

Better health is an obvious benefit. MenAfriVac reduced suspected meningitis cases by 57 percent in the overall population and more than 99 percent among vaccinated individuals.

Lower healthcare costs are another benefit. One study done in Togo found that the cold chain-related costs increased the per dose vaccine price up to 11-fold. The ability to ship the vaccines using the usual cold chain, but transporting them at ambient temperatures for the final few days cut the cost in half.

There are environmental benefits, too, such as reducing fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Cold chain transports consume 20 percent more fuel than non-cold chain shipping, due to refrigeration equipment, according to the International Trade Administration.

A study by researchers at Johns Hopkins University compared the greenhouse gas emissions of the new, oral Vaxart COVID-19 vaccine (which doesn’t require refrigeration) with four intramuscular vaccines (which require refrigeration or freezing). While the Vaxart vaccine is still in clinical trials, the study found that “up to 82.25 million kilograms of CO2 could be averted by using oral vaccines in the U.S. alone.” That is akin to taking 17,700 vehicles out of service for one year.

Although tardigrades’ protective proteins won’t be a component of biologic pharmaceutics for several years, scientists are proving that this approach is viable. They are hopeful that a day will come when vaccines and biologics can be delivered anywhere in the world without needing refrigerators or freezers en route.