Can Genetic Testing Help Shed Light on the Autism Epidemic?

A little boy standing by a window in contemplation. (© altanaka/Fotolia)

Autism cases are still on the rise, and scientists don't know why. In April, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that rates of autism had increased once again, now at an estimated 1 in 59 children up from 1 in 68 just two years ago. Rates have been climbing steadily since 2007 when the CDC initially estimated that 1 in 150 children were on the autism spectrum.

Some clinicians are concerned that the creeping expansion of autism is causing the diagnosis to lose its meaning.

The standard explanation for this increase has been the expansion of the definition of autism to include milder forms like Asperger's, as well as a heightened awareness of the condition that has improved screening efforts. For example, the most recent jump is attributed to children in minority communities being diagnosed who might have previously gone under the radar. In addition, more federally funded resources are available to children with autism than other types of developmental disorders, which may prompt families or physicians to push harder for a diagnosis.

Some clinicians are concerned that the creeping expansion of autism is causing the diagnosis to lose its meaning. William Graf, a pediatric neurologist at Connecticut Children's Medical Center, says that when a nurse tells him that a new patient has a history of autism, the term is no longer a useful description. "Even though I know this topic extremely well, I cannot picture the child anymore," he says. "Use the words mild, moderate, or severe. Just give me a couple more clues, because when you say autism today, I have no idea what people are talking about anymore."

Genetic testing has emerged as one potential way to remedy the overly broad label by narrowing down a heterogeneous diagnosis to a specific genetic disorder. According to Suma Shankar, a medical geneticist at the University of California, Davis, up to 60 percent of autism cases could be attributed to underlying genetic causes. Common examples include Fragile X Syndrome or Rett Syndrome—neurodevelopmental disorders that are caused by mutations in individual genes and are behaviorally classified as autism.

With more than 500 different mutations associated with autism, very few additional diagnoses provide meaningful information.

Having a genetic diagnosis in addition to an autism diagnosis can help families in several ways, says Shankar. Knowing the genetic origin can alert families to other potential health problems that are linked to the mutation, such as heart defects or problems with the immune system. It may also help clinicians provide more targeted behavioral therapies and could one day lead to the development of drug treatments for underlying neurochemical abnormalities. "It will pave the way to begin to tease out treatments," Shankar says.

When a doctor diagnoses a child as having a specific genetic condition, the label of autism is still kept because it is more well-known and gives the child access to more state-funded resources. Children can thus be diagnosed with multiple conditions: autism spectrum disorder and their specific gene mutation. However, with more than 500 different mutations associated with autism, very few additional diagnoses provide meaningful information. What's more, the presence or absence of a mutation doesn't necessarily indicate whether the child is on the mild or severe end of the autism spectrum.

Because of this, Graf doubts that genetic classifications are really that useful. He tells the story of a boy with epilepsy and severe intellectual disabilities who was diagnosed with autism as a young child. Years later, Graf ordered genetic testing for the boy and discovered that he had a mutation in the gene SYNGAP1. However, this knowledge didn't change the boy's autism status. "That diagnosis [SYNGAP1] turns out to be very specific for him, but it will never be a household name. Biologically it's good to know, and now it's all over his chart. But on a societal level he still needs this catch-all label [of autism]," Graf says.

"It gives some information, but to what degree does that change treatment or prognosis?"

Jennifer Singh, a sociologist at Georgia Tech who wrote the book Multiple Autisms: Spectrums of Advocacy and Genomic Science, agrees. "I don't know that the knowledge gained from just having a gene that's linked to autism," is that beneficial, she says. "It gives some information, but to what degree does that change treatment or prognosis? Because at the end of the day you have to address the issues that are at hand, whatever they might be."

As more children are diagnosed with autism, knowledge of the underlying genetic mutation causing the condition could help families better understand the diagnosis and anticipate their child's developmental trajectory. However, for the vast majority, an additional label provides little clarity or consolation.

Instead of spending money on genetic screens, Singh thinks the resources would be better used on additional services for people who don't have access to behavioral, speech, or occupational therapy. "Things that are really going to matter for this child in their future," she says.

Is a Successful HIV Vaccine Finally on the Horizon?

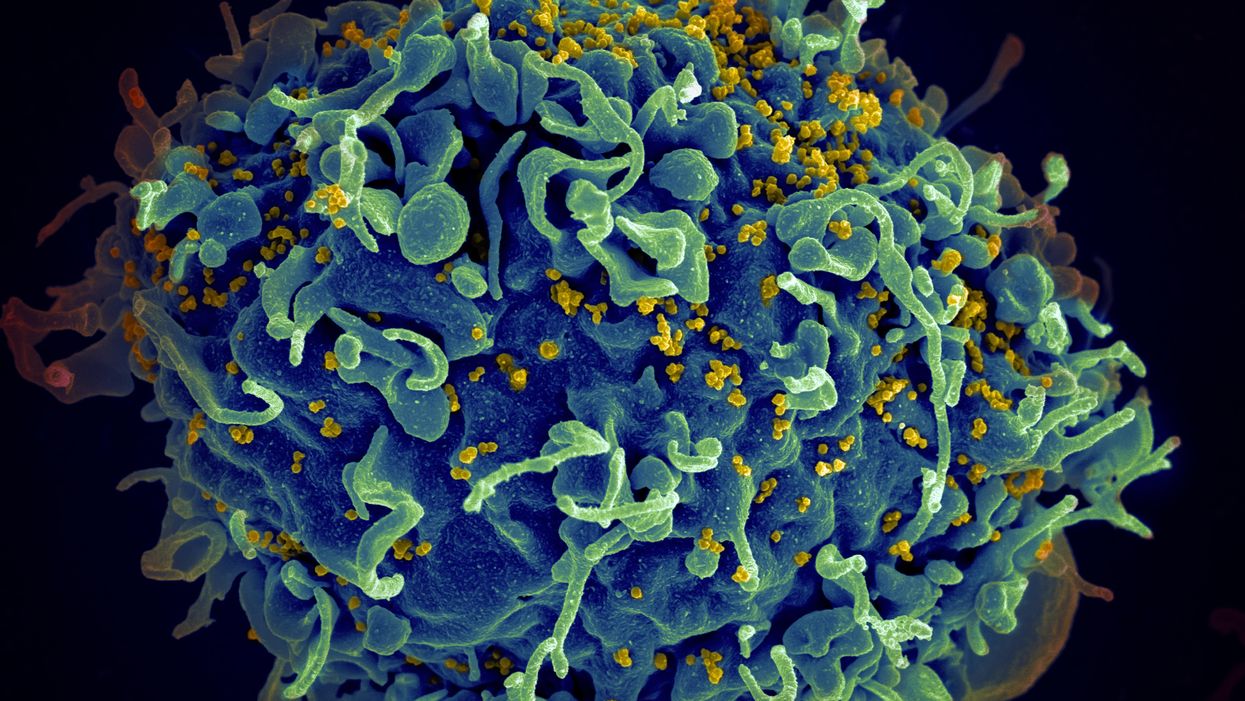

The HIV virus (yellow) infecting a human cell.

Few vaccines have been as complicated—and filled with false starts and crushed hopes—as the development of an HIV vaccine.

While antivirals help HIV-positive patients live longer and reduce viral transmission to virtually nil, these medications must be taken for life, and preventative medications like pre-exposure prophylaxis, known as PrEP, need to be taken every day to be effective. Vaccines, even if they need boosters, would make prevention much easier.

In August, Moderna began human trials for two HIV vaccine candidates based on messenger RNA.

As they have with the Covid-19 pandemic, mRNA vaccines could change the game. The technology could be applied for gene editing therapy, cancer, other infectious diseases—even a universal influenza vaccine.

In the past, three other mRNA vaccines completed phase-2 trials without success. But the easily customizable platforms mean the vaccines can be tweaked better to target HIV as researchers learn more.

Ever since HIV was discovered as the virus causing AIDS, researchers have been searching for a vaccine. But the decades-long journey has so far been fruitless; while some vaccine candidates showed promise in early trials, none of them have worked well among later-stage clinical trials.

There are two main reasons for this: HIV evolves incredibly quickly, and the structure of the virus makes it very difficult to neutralize with antibodies.

"We in HIV medicine have been desperate to find a vaccine that has effectiveness, but this goal has been elusive so far."

"You know the panic that goes on when a new coronavirus variant surfaces?" asked John Moore, professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine who has researched HIV vaccines for 25 years. "With HIV, that kind of variation [happens] pretty much every day in everybody who's infected. It's just orders of magnitude more variable a virus."

Vaccines like these usually work by imitating the outer layer of a virus to teach cells how to recognize and fight off the real thing off before it enters the cell. "If you can prevent landing, you can essentially keep the virus out of the cell," said Larry Corey, the former president and director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center who helped run a recent trial of a Johnson & Johnson HIV vaccine candidate, which failed its first efficacy trial.

Like the coronavirus, HIV also has a spike protein with a receptor-binding domain—what Moore calls "the notorious RBD"—that could be neutralized with antibodies. But while that target sticks out like a sore thumb in a virus like SARS-CoV-2, in HIV it's buried under a dense shield. That's not the only target for neutralizing the virus, but all of the targets evolve rapidly and are difficult to reach.

"We understand these targets. We know where they are. But it's still proving incredibly difficult to raise antibodies against them by vaccination," Moore said.

In fact, mRNA vaccines for HIV have been under development for years. The Covid vaccines were built on decades of that research. But it's not as simple as building on this momentum, because of how much more complicated HIV is than SARS-CoV-2, researchers said.

"They haven't succeeded because they were not designed appropriately and haven't been able to induce what is necessary for them to induce," Moore said. "The mRNA technology will enable you to produce a lot of antibodies to the HIV envelope, but if they're the wrong antibodies that doesn't solve the problem."

Part of the problem is that the HIV vaccines have to perform better than our own immune systems. Many vaccines are created by imitating how our bodies overcome an infection, but that doesn't happen with HIV. Once you have the virus, you can't fight it off on your own.

"The human immune system actually does not know how to innately cure HIV," Corey said. "We needed to improve upon the human immune system to make it quicker… with Covid. But we have to actually be better than the human immune system" with HIV.

But in the past few years, there have been impressive leaps in understanding how an HIV vaccine might work. Scientists have known for decades that neutralizing antibodies are key for a vaccine. But in 2010 or so, they were able to mimic the HIV spike and understand how antibodies need to disable the virus. "It helps us understand the nature of the problem, but doesn't instantly solve the problem," Moore said. "Without neutralizing antibodies, you don't have a chance."

Because the vaccines need to induce broadly neutralizing antibodies, and because it's very difficult to neutralize the highly variable HIV, any vaccine will likely be a series of shots that teach the immune system to be on the lookout for a variety of potential attacks.

"Each dose is going to have to have a different purpose," Corey said. "And we hope by the end of the third or fourth dose, we will achieve the level of neutralization that we want."

That's not ideal, because each individual component has to be made and tested—and four shots make the vaccine harder to administer.

"You wouldn't even be going down that route, if there was a better alternative," Moore said. "But there isn't a better alternative."

The mRNA platform is exciting because it is easily customizable, which is especially important in fighting against a shapeshifting, complicated virus. And the mRNA platform has shown itself, in the Covid pandemic, to be safe and quick to make. Effective Covid vaccines were comparatively easy to develop, since the coronavirus is easier to battle than HIV. But companies like Moderna are capitalizing on their success to launch other mRNA therapeutics and vaccines, including the HIV trial.

"You can make the vaccine in two months, three months, in a research lab, and not a year—and the cost of that is really less," Corey said. "It gives us a chance to try many more options, if we've got a good response."

In a trial on macaque monkeys, the Moderna vaccine reduced the chances of infection by 85 percent. "The mRNA platform represents a very promising approach for the development of an HIV vaccine in the future," said Dr. Peng Zhang, who is helping lead the trial at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Moderna's trial in humans represents "a very exciting possibility for the prevention of HIV infection," Dr. Monica Gandhi, director of the UCSF-Gladstone Center for AIDS Research, said in an email. "We in HIV medicine have been desperate to find a vaccine that has effectiveness, but this goal has been elusive so far."

If a successful HIV vaccine is developed, the series of shots could include an mRNA shot that primes the immune system, followed by protein subunits that generate the necessary antibodies, Moore said.

"I think it's the only thing that's worth doing," he said. "Without something complicated like that, you have no chance of inducing broadly neutralizing antibodies."

"I can't guarantee you that's going to work," Moore added. "It may completely fail. But at least it's got some science behind it."

New Podcast: The Lead Scientist for the NASA Mission to Venus

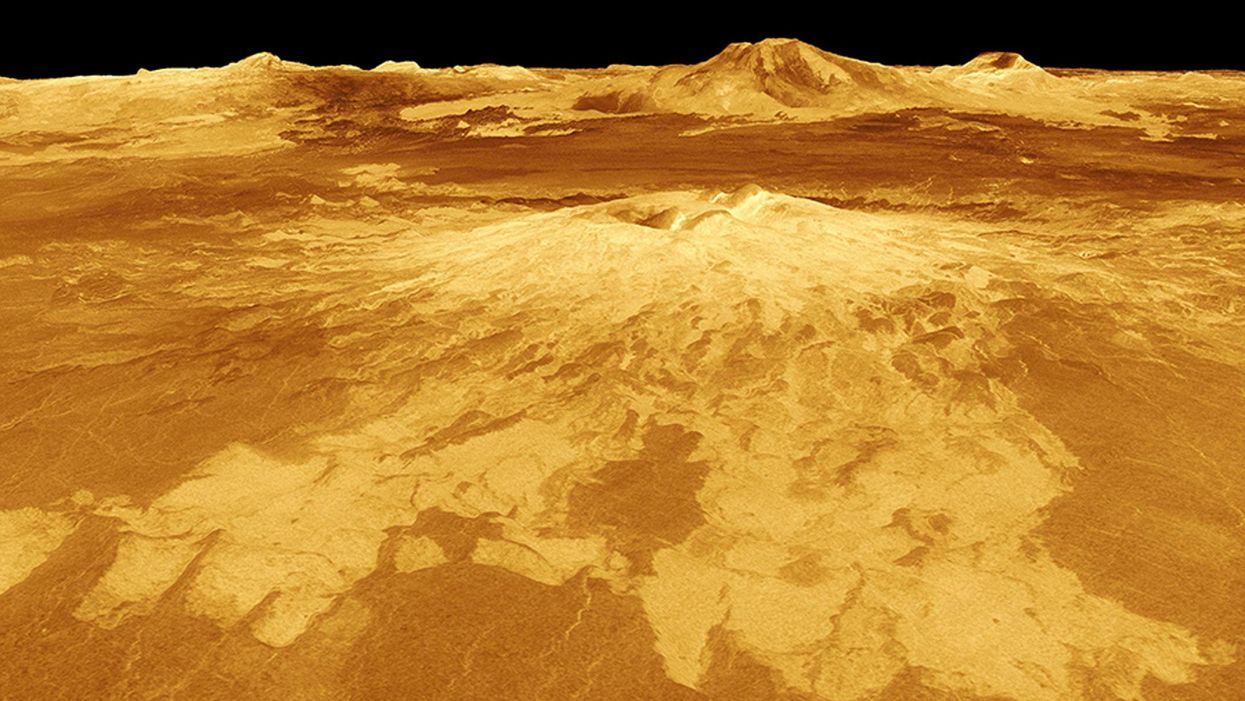

The volcano Sapas Mons is displayed in the center of this computer-generated three-dimensional perspective view of the surface of Venus.

The "Making Sense of Science" podcast features interviews with leading medical and scientific experts about the latest developments and the big ethical and societal questions they raise. This monthly podcast is hosted by journalist Kira Peikoff, founding editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

This month, our guest is JPL's Dr. Suzanne Smrekar, who will be pushing the boundaries of knowledge about the planet Venus during the upcoming VERITAS mission set to launch in 2028. Why did Earth's twin planet develop so differently than our own? Could Venus ever have hosted life? What is the bigger purpose for humanity in studying the solar system -- is it purely scientific, or is it also a matter of art and philosophy? Hear Dr. Smrekar discuss all this and more on the latest episode.

Watch the 30-Second Trailer:

Listen to the Episode:

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.