Can Genetic Testing Help Shed Light on the Autism Epidemic?

A little boy standing by a window in contemplation. (© altanaka/Fotolia)

Autism cases are still on the rise, and scientists don't know why. In April, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that rates of autism had increased once again, now at an estimated 1 in 59 children up from 1 in 68 just two years ago. Rates have been climbing steadily since 2007 when the CDC initially estimated that 1 in 150 children were on the autism spectrum.

Some clinicians are concerned that the creeping expansion of autism is causing the diagnosis to lose its meaning.

The standard explanation for this increase has been the expansion of the definition of autism to include milder forms like Asperger's, as well as a heightened awareness of the condition that has improved screening efforts. For example, the most recent jump is attributed to children in minority communities being diagnosed who might have previously gone under the radar. In addition, more federally funded resources are available to children with autism than other types of developmental disorders, which may prompt families or physicians to push harder for a diagnosis.

Some clinicians are concerned that the creeping expansion of autism is causing the diagnosis to lose its meaning. William Graf, a pediatric neurologist at Connecticut Children's Medical Center, says that when a nurse tells him that a new patient has a history of autism, the term is no longer a useful description. "Even though I know this topic extremely well, I cannot picture the child anymore," he says. "Use the words mild, moderate, or severe. Just give me a couple more clues, because when you say autism today, I have no idea what people are talking about anymore."

Genetic testing has emerged as one potential way to remedy the overly broad label by narrowing down a heterogeneous diagnosis to a specific genetic disorder. According to Suma Shankar, a medical geneticist at the University of California, Davis, up to 60 percent of autism cases could be attributed to underlying genetic causes. Common examples include Fragile X Syndrome or Rett Syndrome—neurodevelopmental disorders that are caused by mutations in individual genes and are behaviorally classified as autism.

With more than 500 different mutations associated with autism, very few additional diagnoses provide meaningful information.

Having a genetic diagnosis in addition to an autism diagnosis can help families in several ways, says Shankar. Knowing the genetic origin can alert families to other potential health problems that are linked to the mutation, such as heart defects or problems with the immune system. It may also help clinicians provide more targeted behavioral therapies and could one day lead to the development of drug treatments for underlying neurochemical abnormalities. "It will pave the way to begin to tease out treatments," Shankar says.

When a doctor diagnoses a child as having a specific genetic condition, the label of autism is still kept because it is more well-known and gives the child access to more state-funded resources. Children can thus be diagnosed with multiple conditions: autism spectrum disorder and their specific gene mutation. However, with more than 500 different mutations associated with autism, very few additional diagnoses provide meaningful information. What's more, the presence or absence of a mutation doesn't necessarily indicate whether the child is on the mild or severe end of the autism spectrum.

Because of this, Graf doubts that genetic classifications are really that useful. He tells the story of a boy with epilepsy and severe intellectual disabilities who was diagnosed with autism as a young child. Years later, Graf ordered genetic testing for the boy and discovered that he had a mutation in the gene SYNGAP1. However, this knowledge didn't change the boy's autism status. "That diagnosis [SYNGAP1] turns out to be very specific for him, but it will never be a household name. Biologically it's good to know, and now it's all over his chart. But on a societal level he still needs this catch-all label [of autism]," Graf says.

"It gives some information, but to what degree does that change treatment or prognosis?"

Jennifer Singh, a sociologist at Georgia Tech who wrote the book Multiple Autisms: Spectrums of Advocacy and Genomic Science, agrees. "I don't know that the knowledge gained from just having a gene that's linked to autism," is that beneficial, she says. "It gives some information, but to what degree does that change treatment or prognosis? Because at the end of the day you have to address the issues that are at hand, whatever they might be."

As more children are diagnosed with autism, knowledge of the underlying genetic mutation causing the condition could help families better understand the diagnosis and anticipate their child's developmental trajectory. However, for the vast majority, an additional label provides little clarity or consolation.

Instead of spending money on genetic screens, Singh thinks the resources would be better used on additional services for people who don't have access to behavioral, speech, or occupational therapy. "Things that are really going to matter for this child in their future," she says.

Researchers claimed they built a breakthrough superconductor. Social media shot it down almost instantly.

In July, South Korean scientists posted a paper finding they had achieved superconductivity - a claim that was debunked within days.

Harsh Mathur was a graduate physics student at Yale University in late 1989 when faculty announced they had failed to replicate claims made by scientists at the University of Utah and the University of Wolverhampton in England.

Such work is routine. Replicating or attempting to replicate the contraptions, calculations and conclusions crafted by colleagues is foundational to the scientific method. But in this instance, Yale’s findings were reported globally.

“I had a ringside view, and it was crazy,” recalls Mathur, now a professor of physics at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

Yale’s findings drew so much attention because initial experiments by Stanley Pons of Utah and Martin Fleischmann of Wolverhampton led to a startling claim: They were able to fuse atoms at room temperature – a scientific El Dorado known as “cold fusion.”

Nuclear fusion powers the stars in the universe. However, star cores must be at least 23.4 million degrees Fahrenheit and under extraordinary pressure to achieve fusion. Pons and Fleischmann claimed they had created an almost limitless source of power achievable at any temperature.

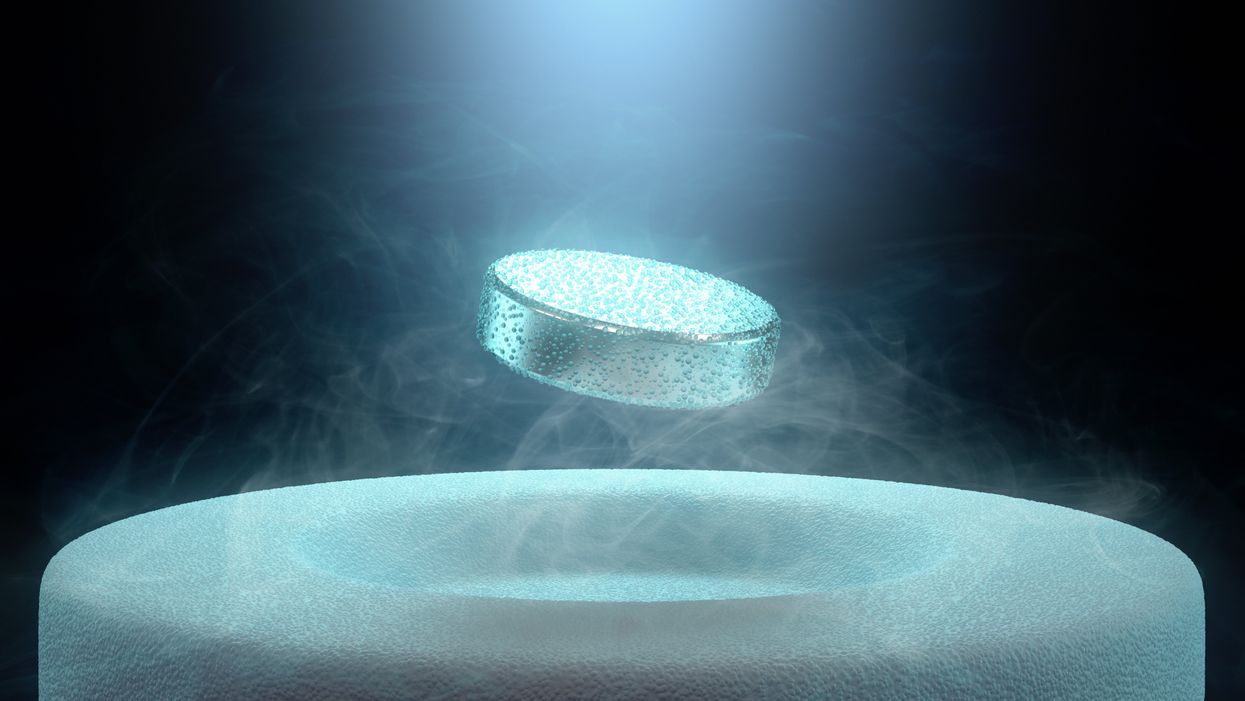

Like fusion, superconductivity can only be achieved in mostly impractical circumstances.

But about six months after they made their startling announcement, the pair’s findings were discredited by researchers at Yale and the California Institute of Technology. It was one of the first instances of a major scientific debunking covered by mass media.

Some scholars say the media attention for cold fusion stemmed partly from a dazzling announcement made three years prior in 1986: Scientists had created the first “superconductor” – material that could transmit electrical current with little or no resistance. It drew global headlines – and whetted the public’s appetite for announcements of scientific breakthroughs that could cause economic transformations.

But like fusion, superconductivity can only be achieved in mostly impractical circumstances: It must operate either at temperatures of at least negative 100 degrees Fahrenheit, or under pressures of around 150,000 pounds per square inch. Superconductivity that functions in closer to a normal environment would cut energy costs dramatically while also opening infinite possibilities for computing, space travel and other applications.

In July, a group of South Korean scientists posted material claiming they had created an iron crystalline substance called LK-99 that could achieve superconductivity at slightly above room temperature and at ambient pressure. The group partners with the Quantum Energy Research Centre, a privately-held enterprise in Seoul, and their claims drew global headlines.

Their work was also debunked. But in the age of internet and social media, the process was compressed from half-a-year into days. And it did not require researchers at world-class universities.

One of the most compelling critiques came from Derrick VanGennep. Although he works in finance, he holds a Ph.D. in physics and held a postdoctoral position at Harvard. The South Korean researchers had posted a video of a nugget of LK-99 in what they claimed was the throes of the Meissner effect – an expulsion of the substance’s magnetic field that would cause it to levitate above a magnet. Unless Hollywood magic is involved, only superconducting material can hover in this manner.

That claim made VanGennep skeptical, particularly since LK-99’s levitation appeared unenthusiastic at best. In fact, a corner of the material still adhered to the magnet near its center. He thought the video demonstrated ferromagnetism – two magnets repulsing one another. He mixed powdered graphite with super glue, stuck iron filings to its surface and mimicked the behavior of LK-99 in his own video, which was posted alongside the researchers’ video.

VanGennep believes the boldness of the South Korean claim was what led to him and others in the scientific community questioning it so quickly.

“The swift replication attempts stemmed from the combination of the extreme claim, the fact that the synthesis for this material is very straightforward and fast, and the amount of attention that this story was getting on social media,” he says.

But practicing scientists were suspicious of the data as well. Michael Norman, director of the Argonne Quantum Institute at the Argonne National Laboratory just outside of Chicago, had doubts immediately.

Will this saga hurt or even affect the careers of the South Korean researchers? Possibly not, if the previous fusion example is any indication.

“It wasn’t a very polished paper,” Norman says of the Korean scientists’ work. That opinion was reinforced, he adds, when it turned out the paper had been posted online by one of the researchers prior to seeking publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Although Norman and Mathur say that is routine with scientific research these days, Norman notes it was posted by one of the junior researchers over the doubts of two more senior scientists on the project.

Norman also raises doubts about the data reported. Among other issues, he observes that the samples created by the South Korean researchers contained traces of copper sulfide that could inadvertently amplify findings of conductivity.

The lack of the Meissner effect also caught Mathur’s attention. “Ferromagnets tend to be unstable when they levitate,” he says, adding that the video “just made me feel unconvinced. And it made me feel like they hadn't made a very good case for themselves.”

Will this saga hurt or even affect the careers of the South Korean researchers? Possibly not, if the previous fusion example is any indication. Despite being debunked, cold fusion claimants Pons and Fleischmann didn’t disappear. They moved their research to automaker Toyota’s IMRA laboratory in France, which along with the Japanese government spent tens of millions of dollars on their work before finally pulling the plug in 1998.

Fusion has since been created in laboratories, but being unable to reproduce the density of a star’s core would require excruciatingly high temperatures to achieve – about 160 million degrees Fahrenheit. A recently released Government Accountability Office report concludes practical fusion likely remains at least decades away.

However, like Pons and Fleischman, the South Korean researchers are not going anywhere. They claim that LK-99’s Meissner effect is being obscured by the fact the substance is both ferromagnetic and diamagnetic. They have filed for a patent in their country. But for now, those claims remain chimerical.

In the meantime, the consensus as to when a room temperature superconductor will be achieved is mixed. VenGennep – who studied the issue during his graduate and postgraduate work – puts the chance of creating such a superconductor by 2050 at perhaps 50-50. Mathur believes it could happen sooner, but adds that research on the topic has been going on for nearly a century, and that it has seen many plateaus.

“There's always this possibility that there's going to be something out there that we're going to discover unexpectedly,” Norman notes. The only certainty in this age of social media is that it will be put through the rigors of replication instantly.

Scientists implant brain cells to counter Parkinson's disease

In a recent research trial, patients with Parkinson's disease reported that their symptoms had improved after stem cells were implanted into their brains. Martin Taylor, far right, was diagnosed at age 32.

Martin Taylor was only 32 when he was diagnosed with Parkinson's, a disease that causes tremors, stiff muscles and slow physical movement - symptoms that steadily get worse as time goes on.

“It's horrible having Parkinson's,” says Taylor, a data analyst, now 41. “It limits my ability to be the dad and husband that I want to be in many cruel and debilitating ways.”

Today, more than 10 million people worldwide live with Parkinson's. Most are diagnosed when they're considerably older than Taylor, after age 60. Although recent research has called into question certain aspects of the disease’s origins, Parkinson’s eventually kills the nerve cells in the brain that produce dopamine, a signaling chemical that carries messages around the body to control movement. Many patients have lost 60 to 80 percent of these cells by the time they are diagnosed.

For years, there's been little improvement in the standard treatment. Patients are typically given the drug levodopa, a chemical that's absorbed by the brain’s nerve cells, or neurons, and converted into dopamine. This drug addresses the symptoms but has no impact on the course of the disease as patients continue to lose dopamine producing neurons. Eventually, the treatment stops working effectively.

BlueRock Therapeutics, a cell therapy company based in Massachusetts, is taking a different approach by focusing on the use of stem cells, which can divide into and generate new specialized cells. The company makes the dopamine-producing cells that patients have lost and inserts these cells into patients' brains. “We have a disease with a high unmet need,” says Ahmed Enayetallah, the senior vice president and head of development at BlueRock. “We know [which] cells…are lost to the disease, and we can make them. So it really came together to use stem cells in Parkinson's.”

In a phase 1 research trial announced late last month, patients reported that their symptoms had improved after a year of treatment. Brain scans also showed an increased number of neurons generating dopamine in patients’ brains.

Increases in dopamine signals

The recent phase 1 trial focused on deploying BlueRock’s cell therapy, called bemdaneprocel, to treat 12 patients suffering from Parkinson’s. The team developed the new nerve cells and implanted them into specific locations on each side of the patient's brain through two small holes in the skull made by a neurosurgeon. “We implant cells into the places in the brain where we think they have the potential to reform the neural networks that are lost to Parkinson's disease,” Enayetallah says. The goal is to restore motor function to patients over the long-term.

Five patients were given a relatively low dose of cells while seven got higher doses. Specialized brain scans showed evidence that the transplanted cells had survived, increasing the overall number of dopamine producing cells. The team compared the baseline number of these cells before surgery to the levels one year later. “The scans tell us there is evidence of increased dopamine signals in the part of the brain affected by Parkinson's,” Enayetallah says. “Normally you’d expect the signal to go down in untreated Parkinson’s patients.”

"I think it has a real chance to reverse motor symptoms, essentially replacing a missing part," says Tilo Kunath, a professor of regenerative neurobiology at the University of Edinburgh.

The team also asked patients to use a specific type of home diary to log the times when symptoms were well controlled and when they prevented normal activity. After a year of treatment, patients taking the higher dose reported symptoms were under control for an average of 2.16 hours per day above their baselines. At the smaller dose, these improvements were significantly lower, 0.72 hours per day. The higher-dose patients reported a corresponding decrease in the amount of time when symptoms were uncontrolled, by an average of 1.91 hours, compared to 0.75 hours for the lower dose. The trial was safe, and patients tolerated the year of immunosuppression needed to make sure their bodies could handle the foreign cells.

Claire Bale, the associate director of research at Parkinson's U.K., sees the promise of BlueRock's approach, while noting the need for more research on a possible placebo effect. The trial participants knew they were getting the active treatment, and placebo effects are known to be a potential factor in Parkinson’s research. Even so, “The results indicate that this therapy produces improvements in symptoms for Parkinson's, which is very encouraging,” Bale says.

Tilo Kunath, a professor of regenerative neurobiology at the University of Edinburgh, also finds the results intriguing. “I think it's excellent,” he says. “I think it has a real chance to reverse motor symptoms, essentially replacing a missing part.” However, it could take time for this therapy to become widely available, Kunath says, and patients in the late stages of the disease may not benefit as much. “Data from cell transplantation with fetal tissue in the 1980s and 90s show that cells did not survive well and release dopamine in these [late-stage] patients.”

Searching for the right approach

There's a long history of using cell therapy as a treatment for Parkinson's. About four decades ago, scientists at the University of Lund in Sweden developed a method in which they transferred parts of fetal brain tissue to patients with Parkinson's so that their nerve cells would produce dopamine. Many benefited, and some were able to stop their medication. However, the use of fetal tissue was highly controversial at that time, and the tissues were difficult to obtain. Later trials in the U.S. showed that people benefited only if a significant amount of the tissue was used, and several patients experienced side effects. Eventually, the work lost momentum.

“Like many in the community, I'm aware of the long history of cell therapy,” says Taylor, the patient living with Parkinson's. “They've long had that cure over the horizon.”

In 2000, Lorenz Studer led a team at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Centre, in New York, to find the chemical signals needed to get stem cells to differentiate into cells that release dopamine. Back then, the team managed to make cells that produced some dopamine, but they led to only limited improvements in animals. About a decade later, in 2011, Studer and his team found the specific signals needed to guide embryonic cells to become the right kind of dopamine producing cells. Their experiments in mice, rats and monkeys showed that their implanted cells had a significant impact, restoring lost movement.

Studer then co-founded BlueRock Therapeutics in 2016. Forming the most effective stem cells has been one of the biggest challenges, says Enayetallah, the BlueRock VP. “It's taken a lot of effort and investment to manufacture and make the cells at the right scale under the right conditions.” The team is now using cells that were first isolated in 1998 at the University of Wisconsin, a major advantage because they’re available in a virtually unlimited supply.

Other efforts underway

In the past several years, University of Lund researchers have begun to collaborate with the University of Cambridge on a project to use embryonic stem cells, similar to BlueRock’s approach. They began clinical trials this year.

A company in Japan called Sumitomo is using a different strategy; instead of stem cells from embryos, they’re reprogramming adults' blood or skin cells into induced pluripotent stem cells - meaning they can turn into any cell type - and then directing them into dopamine producing neurons. Although Sumitomo started clinical trials earlier than BlueRock, they haven’t yet revealed any results.

“It's a rapidly evolving field,” says Emma Lane, a pharmacologist at the University of Cardiff who researches clinical interventions for Parkinson’s. “But BlueRock’s trial is the first full phase 1 trial to report such positive findings with stem cell based therapies.” The company’s upcoming phase 2 research will be critical to show how effectively the therapy can improve disease symptoms, she added.

The cure over the horizon

BlueRock will continue to look at data from patients in the phase 1 trial to monitor the treatment’s effects over a two-year period. Meanwhile, the team is planning the phase 2 trial with more participants, including a placebo group.

For patients with Parkinson’s like Martin Taylor, the therapy offers some hope, though Taylor recognizes that more research is needed.

BlueRock Therapeutics

“Like many in the community, I'm aware of the long history of cell therapy,” he says. “They've long had that cure over the horizon.” His expectations are somewhat guarded, he says, but, “it's certainly positive to see…movement in the field again.”

"If we can demonstrate what we’re seeing today in a more robust study, that would be great,” Enayetallah says. “At the end of the day, we want to address that unmet need in a field that's been waiting for a long time.”

Editor's note: The company featured in this piece, BlueRock Therapeutics, is a portfolio company of Leaps by Bayer, which is a sponsor of Leaps.org. BlueRock was acquired by Bayer Pharmaceuticals in 2019. Leaps by Bayer and other sponsors have never exerted influence over Leaps.org content or contributors.