A blood test may catch colorectal cancer before it's too late

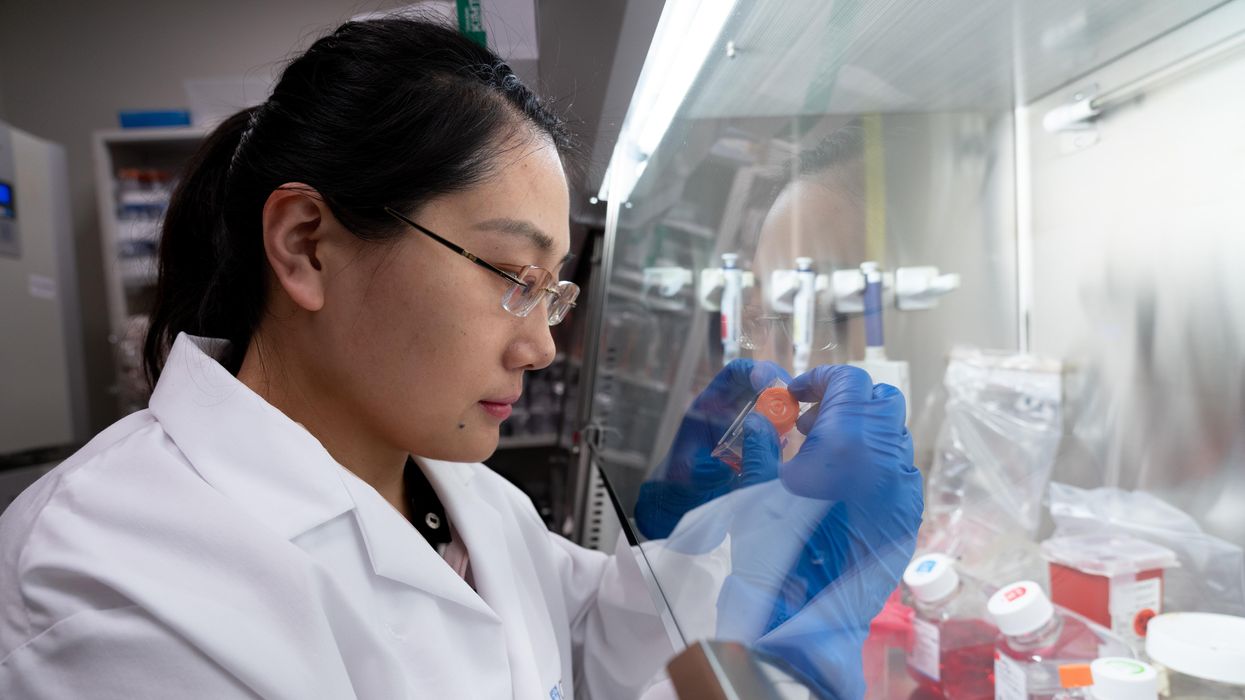

A scientist works on a blood test in the Ajay Goel Lab, one of many labs that are developing blood tests to screen for different types of cancer.

Soon it may be possible to find different types of cancer earlier than ever through a simple blood test.

Among the many blood tests in development, researchers announced in July that they have developed one that may screen for early-onset colorectal cancer. The new potential screening tool, detailed in a study in the journal Gastroenterology, represents a major step in noninvasively and inexpensively detecting nonhereditary colorectal cancer at an earlier and more treatable stage.

In recent years, this type of cancer has been on the upswing in adults under age 50 and in those without a family history. In 2021, the American Cancer Society's revised guidelines began recommending that colorectal cancer screenings with colonoscopy begin at age 45. But that still wouldn’t catch many early-onset cases among people in their 20s and 30s, says Ajay Goel, professor and chair of molecular diagnostics and experimental therapeutics at City of Hope, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit cancer research and treatment center that developed the new blood test.

“These people will mostly be missed because they will never be screened for it,” Goel says. Overall, colorectal cancer is the fourth most common malignancy, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Goel is far from the only one working on this. Dozens of companies are in the process of developing blood tests to screen for different types of malignancies.

Some estimates indicate that between one-fourth and one-third of all newly diagnosed colorectal cancers are early-onset. These patients generally present with more aggressive and advanced disease at diagnosis compared to late-onset colorectal cancer detected in people 50 years or older.

To develop his test, Goel examined publicly available datasets and figured out that changes in novel microRNAs, or miRNAs, which regulate the expression of genes, occurred in people with early-onset colorectal cancer. He confirmed these biomarkers by looking for them in the blood of 149 patients who had the early-onset form of the disease. In particular, Goel and his team of researchers were able to pick out four miRNAs that serve as a telltale sign of this cancer when they’re found in combination with each other.

The blood test is being validated by following another group of patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. “We have filed for intellectual property on this invention and are currently seeking biotech/pharma partners to license and commercialize this invention,” Goel says.

He’s far from the only one working on this. Dozens of companies are in the process of developing blood tests to screen for different types of malignancies, says Timothy Rebbeck, a professor of cancer prevention at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. But, he adds, “It’s still very early, and the technology still needs a lot of work before it will revolutionize early detection.”

The accuracy of the early detection blood tests for cancer isn’t yet where researchers would like it to be. To use these tests widely in people without cancer, a very high degree of precision is needed, says David VanderWeele, interim director of the OncoSET Molecular Tumor Board at Northwestern University’s Lurie Cancer Center in Chicago.

Otherwise, “you’re going to cause a lot of anxiety unnecessarily if people have false-positive tests,” VanderWeele says. So far, “these tests are better at finding cancer when there’s a higher burden of cancer present,” although the goal is to detect cancer at the earliest stages. Even so, “we are making progress,” he adds.

While early detection is known to improve outcomes, most cancers are detected too late, often after they metastasize and people develop symptoms. Only five cancer types have recommended standard screenings, none of which involve blood tests—breast, cervical, colorectal, lung (smokers considered at risk) and prostate cancers, says Trish Rowland, vice president of corporate communications at GRAIL, a biotechnology company in Menlo Park, Calif., which developed a multi-cancer early detection blood test.

These recommended screenings check for individual cancers rather than looking for any form of cancer someone may have. The devil lies in the fact that cancers without widespread screening recommendations represent the vast majority of cancer diagnoses and most cancer deaths.

GRAIL’s Galleri multi-cancer early detection test is designed to find more cancers at earlier stages by analyzing DNA shed into the bloodstream by cells—with as few false positives as possible, she says. The test is currently available by prescription only for those with an elevated risk of cancer. Consumers can request it from their healthcare or telemedicine provider. “Galleri can detect a shared cancer signal across more than 50 types of cancers through a simple blood draw,” Rowland says, adding that it can be integrated into annual health checks and routine blood work.

Cancer patients—even those with early and curable disease—often have tumor cells circulating in their blood. “These tumor cells act as a biomarker and can be used for cancer detection and diagnosis,” says Andrew Wang, a radiation oncologist and professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “Our research goal is to be able to detect these tumor cells to help with cancer management.” Collaborating with Seungpyo Hong, the Milton J. Henrichs Chair and Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy, “we have developed a highly sensitive assay to capture these circulating tumor cells.”

Even if the quality of a blood test is superior, finding cancer early doesn’t always mean it’s absolutely best to treat it. For example, prostate cancer treatment’s potential side effects—the inability to control urine or have sex—may be worse than living with a slow-growing tumor that is unlikely to be fatal. “[The test] needs to tell me, am I going to die of that cancer? And, if I intervene, will I live longer?” says John Marshall, chief of hematology and oncology at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Ajay Goel Lab

A blood test developed at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston helps predict who may benefit from lung cancer screening when it is combined with a risk model based on an individual’s smoking history, according to a study published in January in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The personalized lung cancer risk assessment was more sensitive and specific than the 2021 and 2013 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force criteria.

The study involved participants from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial with a minimum of a 10 pack-year smoking history, meaning they smoked 20 cigarettes per day for ten years. If implemented, the blood test plus model would have found 9.2 percent more lung cancer cases for screening and decreased referral to screening among non-cases by 13.7 percent compared to the 2021 task force criteria, according to Oncology Times.

The conventional type of screening for lung cancer is an annual low-dose CT scan, but only a small percentage of people who are eligible will actually get these scans, says Sam Hanash, professor of clinical cancer prevention and director of MD Anderson’s Center for Global Cancer Early Detection. Such screening is not readily available in most countries.

In methodically searching for blood-based biomarkers for lung cancer screening, MD Anderson researchers developed a simple test consisting of four proteins. These proteins circulating in the blood were at high levels in individuals who had lung cancer or later developed it, Hanash says.

“The interest in blood tests for cancer early detection has skyrocketed in the past few years,” he notes, “due in part to advances in technology and a better understanding of cancer causation, cancer drivers and molecular changes that occur with cancer development.”

However, at the present time, none of the blood tests being considered eliminate the need for screening of eligible subjects using established methods, such as colonoscopy for colorectal cancer. Yet, Hanash says, “they have the potential to complement these modalities.”

Astronaut and Expedition 64 Flight Engineer Soichi Noguchi of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency displays Extra Dwarf Pak Choi plants growing aboard the International Space Station. The plants were grown for the Veggie study which is exploring space agriculture as a way to sustain astronauts on future missions to the Moon or Mars.

Astronauts at the International Space Station today depend on pre-packaged, freeze-dried food, plus some fresh produce thanks to regular resupply missions. This supply chain, however, will not be available on trips further out, such as the moon or Mars. So what are astronauts on long missions going to eat?

Going by the options available now, says Christel Paille, an engineer at the European Space Agency, a lunar expedition is likely to have only dehydrated foods. “So no more fresh product, and a limited amount of already hydrated product in cans.”

For the Mars mission, the situation is a bit more complex, she says. Prepackaged food could still constitute most of their food, “but combined with [on site] production of certain food products…to get them fresh.” A Mars mission isn’t right around the corner, but scientists are currently working on solutions for how to feed those astronauts. A number of boundary-pushing efforts are now underway.

The logistics of growing plants in space, of course, are very different from Earth. There is no gravity, sunlight, or atmosphere. High levels of ionizing radiation stunt plant growth. Plus, plants take up a lot of space, something that is, ironically, at a premium up there. These and special nutritional requirements of spacefarers have given scientists some specific and challenging problems.

To study fresh food production systems, NASA runs the Vegetable Production System (Veggie) on the ISS. Deployed in 2014, Veggie has been growing salad-type plants on “plant pillows” filled with growth media, including a special clay and controlled-release fertilizer, and a passive wicking watering system. They have had some success growing leafy greens and even flowers.

"Ideally, we would like a system which has zero waste and, therefore, needs zero input, zero additional resources."

A larger farming facility run by NASA on the ISS is the Advanced Plant Habitat to study how plants grow in space. This fully-automated, closed-loop system has an environmentally controlled growth chamber and is equipped with sensors that relay real-time information about temperature, oxygen content, and moisture levels back to the ground team at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. In December 2020, the ISS crew feasted on radishes grown in the APH.

“But salad doesn’t give you any calories,” says Erik Seedhouse, a researcher at the Applied Aviation Sciences Department at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida. “It gives you some minerals, but it doesn’t give you a lot of carbohydrates.” Seedhouse also noted in his 2020 book Life Support Systems for Humans in Space: “Integrating the growing of plants into a life support system is a fiendishly difficult enterprise.” As a case point, he referred to the ESA’s Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative (MELiSSA) program that has been running since 1989 to integrate growing of plants in a closed life support system such as a spacecraft.

Paille, one of the scientists running MELiSSA, says that the system aims to recycle the metabolic waste produced by crew members back into the metabolic resources required by them: “The aim is…to come [up with] a closed, sustainable system which does not [need] any logistics resupply.” MELiSSA uses microorganisms to process human excretions in order to harvest carbon dioxide and nitrate to grow plants. “Ideally, we would like a system which has zero waste and, therefore, needs zero input, zero additional resources,” Paille adds.

Microorganisms play a big role as “fuel” in food production in extreme places, including in space. Last year, researchers discovered Methylobacterium strains on the ISS, including some never-seen-before species. Kasthuri Venkateswaran of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, one of the researchers involved in the study, says, “[The] isolation of novel microbes that help to promote the plant growth under stressful conditions is very essential… Certain bacteria can decompose complex matter into a simple nutrient [that] the plants can absorb.” These microbes, which have already adapted to space conditions—such as the absence of gravity and increased radiation—boost various plant growth processes and help withstand the harsh physical environment.

MELiSSA, says Paille, has demonstrated that it is possible to grow plants in space. “This is important information because…we didn’t know whether the space environment was affecting the biological cycle of the plant…[and of] cyanobacteria.” With the scientific and engineering aspects of a closed, self-sustaining life support system becoming clearer, she says, the next stage is to find out if it works in space. They plan to run tests recycling human urine into useful components, including those that promote plant growth.

The MELiSSA pilot plant uses rats currently, and needs to be translated for human subjects for further studies. “Demonstrating the process and well-being of a rat in terms of providing water, sufficient oxygen, and recycling sufficient carbon dioxide, in a non-stressful manner, is one thing,” Paille says, “but then, having a human in the loop [means] you also need to integrate user interfaces from the operational point of view.”

Growing food in space comes with an additional caveat that underscores its high stakes. Barbara Demmig-Adams from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado Boulder explains, “There are conditions that actually will hurt your health more than just living here on earth. And so the need for nutritious food and micronutrients is even greater for an astronaut than for [you and] me.”

Demmig-Adams, who has worked on increasing the nutritional quality of plants for long-duration spaceflight missions, also adds that there is no need to reinvent the wheel. Her work has focused on duckweed, a rather unappealingly named aquatic plant. “It is 100 percent edible, grows very fast, it’s very small, and like some other floating aquatic plants, also produces a lot of protein,” she says. “And here on Earth, studies have shown that the amount of protein you get from the same area of these floating aquatic plants is 20 times higher compared to soybeans.”

Aquatic plants also tend to grow well in microgravity: “Plants that float on water, they don’t respond to gravity, they just hug the water film… They don’t need to know what’s up and what’s down.” On top of that, she adds, “They also produce higher concentrations of really important micronutrients, antioxidants that humans need, especially under space radiation.” In fact, duckweed, when subjected to high amounts of radiation, makes nutrients called carotenoids that are crucial for fighting radiation damage. “We’ve looked at dozens and dozens of plants, and the duckweed makes more of this radiation fighter…than anything I’ve seen before.”

Despite all the scientific advances and promising leads, no one really knows what the conditions so far out in space will be and what new challenges they will bring. As Paille says, “There are known unknowns and unknown unknowns.”

One definite “known” for astronauts is that growing their food is the ideal scenario for space travel in the long term since “[taking] all your food along with you, for best part of two years, that’s a lot of space and a lot of weight,” as Seedhouse says. That said, once they land on Mars, they’d have to think about what to eat all over again. “Then you probably want to start building a greenhouse and growing food there [as well],” he adds.

And that is a whole different challenge altogether.

The Science of Why Adjusting to Omicron Is So Tough

A brain expert weighs in on the cognitive biases that hold us back from adjusting to the new reality of Omicron.

We are sticking our heads into the sand of reality on Omicron, and the results may be catastrophic.

Omicron is over 4 times more infectious than Delta. The Pfizer two-shot vaccine offers only 33% protection from infection. A Pfizer booster vaccine does raises protection to about 75%, but wanes to around 30-40 percent 10 weeks after the booster.

The only silver lining is that Omicron appears to cause a milder illness than Delta. Yet the World Health Organization has warned about the “mildness” narrative.

That’s because the much faster disease transmission and vaccine escape undercut the less severe overall nature of Omicron. That’s why hospitals have a large probability of being overwhelmed, as the Center for Disease Control warned, in this major Omicron wave.

Yet despite this very serious threat, we see the lack of real action. The federal government tightened international travel guidelines and is promoting boosters. Certainly, it’s crucial to get as many people to get their booster – and initial vaccine doses – as soon as possible. But the government is not taking the steps that would be the real game-changers.

Pfizer’s anti-viral drug Paxlovid decreases the risk of hospitalization and death from COVID by 89%. Due to this effectiveness, the FDA approved Pfizer ending the trial early, because it would be unethical to withhold the drug from people in the control group. Yet the FDA chose not to hasten the approval process along with the emergence of Omicron in late November, only getting around to emergency authorization in late December once Omicron took over. That delay meant the lack of Paxlovid for the height of the Omicron wave, since it takes many weeks to ramp up production, resulting in an unknown number of unnecessary deaths.

We humans are prone to falling for dangerous judgment errors called cognitive biases.

Widely available at-home testing would enable people to test themselves quickly, so that those with mild symptoms can quarantine instead of infecting others. Yet the federal government did not make tests available to patients when Omicron emerged in late November. That’s despite the obviousness of the coming wave based on the precedent of South Africa, UK, and Denmark and despite the fact that the government made vaccines freely available. Its best effort was to mandate that insurance cover reimbursements for these kits, which is way too much of a barrier for most people. By the time Omicron took over, the federal government recognized its mistake and ordered 500 million tests to be made available in January. However, that’s far too late. And the FDA also played a harmful role here, with its excessive focus on accuracy going back to mid-2020, blocking the widespread availability of cheap at-home tests. By contrast, Europe has a much better supply of tests, due to its approval of quick and slightly less accurate tests.

Neither do we see meaningful leadership at the level of employers. Some are bringing out the tired old “delay the office reopening” play. For example, Google, Uber, and Ford, along with many others, have delayed the return to the office for several months. Those that already returned are calling for stricter pandemic measures, such as more masks and social distancing, but not changing their work arrangements or adding sufficient ventilation to address the spread of COVID.

Despite plenty of warnings from risk management and cognitive bias experts, leaders are repeating the same mistakes we fell into with Delta. And so are regular people. For example, surveys show that Omicron has had very little impact on the willingness of unvaccinated Americans to get a first vaccine dose, or of vaccinated Americans to get a booster. That’s despite Omicron having taken over from Delta in late December.

What explains this puzzling behavior on both the individual and society level? We humans are prone to falling for dangerous judgment errors called cognitive biases. Rooted in wishful thinking and gut reactions, these mental blindspots lead to poor strategic and financial decisions when evaluating choices.

These cognitive biases stem from the more primitive, emotional, and intuitive part of our brains that ensured survival in our ancestral environment. This quick, automatic reaction of our emotions represents the autopilot system of thinking, one of the two systems of thinking in our brains. It makes good decisions most of the time but also regularly makes certain systematic thinking errors, since it’s optimized to help us survive. In modern society, our survival is much less at risk, and our gut is more likely to compel us to focus on the wrong information to make decisions.

One of the biggest challenges relevant to Omicron is the cognitive bias known as the ostrich effect. Named after the myth that ostriches stick their heads into the sand when they fear danger, the ostrich effect refers to people denying negative reality. Delta illustrated the high likelihood of additional dangerous variants, yet we failed to pay attention to and prepare for such a threat.

We want the future to be normal. We’re tired of the pandemic and just want to get back to pre-pandemic times. Thus, we greatly underestimate the probability and impact of major disruptors, like new COVID variants. That cognitive bias is called the normalcy bias.

When we learn one way of functioning in any area, we tend to stick to that way of functioning. You might have heard of this as the hammer-nail syndrome: when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. That syndrome is called functional fixedness. This cognitive bias causes those used to their old ways of action to reject any alternatives, including to prepare for a new variant.

Our minds naturally prioritize the present. We want what we want now, and downplay the long-term consequences of our current desires. That fallacious mental pattern is called hyperbolic discounting, where we excessively discount the benefits of orienting toward the future and focus on the present. A clear example is focusing on the short-term perceived gains of trying to return to normal over managing the risks of future variants.

The way forward into the future is to defeat cognitive biases and avoid denying reality by rethinking our approach to the future.

The FDA requires a serious overhaul. It’s designed for a non-pandemic environment, where the goal is to have a highly conservative, slow-going, and risk-averse approach so that the public feels confident trusting whatever it approved. That’s simply unacceptable in a fast-moving pandemic, and we are bound to face future pandemics in the future.

The federal government needs to have cognitive bias experts weigh in on federal policy. Putting all of its eggs in one basket – vaccinations – is not a wise move when we face the risks of a vaccine-escaping variant. Its focus should also be on expediting and prioritizing anti-virals, scaling up cheap rapid testing, and subsidizing high-filtration masks.

For employers, instead of dictating a top-down approach to how employees collaborate, companies need to adopt a decentralized team-led approach. Each individual team leader of a rank-and-file employee team should determine what works best for their team. After all, team leaders tend to know much more of what their teams need, after all. Moreover, they can respond to local emergencies like COVID surges.

At the same time, team leaders need to be trained to integrate best practices for hybrid and remote team leadership. Companies transitioned to telework abruptly as part of the March 2020 lockdowns. They fell into the cognitive bias of functional fixedness and transposed their pre-existing, in-office methods of collaboration on remote work. Zoom happy hours are a clear example: The large majority of employees dislike them, and research shows they are disconnecting, rather than connecting.

Yet supervisors continue to use them, despite the existence of much better methods of facilitating colalboration, which have been shown to work, such as virtual water cooler discussions, virtual coworking, and virtual mentoring. Leaders also need to facilitate innovation in hybrid and remote teams through techniques such as virtual asynchronous brainstorming. Finally, team leaders need to adjust performance evaluation to adapt to the needs of hybrid and remote teams.

On an individual level, people built up certain expectations during the first two years of the pandemic, and they don't apply with Omicron. For example, most people still think that a cloth mask is a fine source of protection. In reality, you really need an N-95 mask, since Omicron is so much more infectious. Another example is that many people don’t realize that symptom onset is much quicker with Omicron, and they aren’t prepared for the consequences.

Remember that we have a huge number of people who are asymptomatic, often without knowing it, due to the much higher mildness of Omicron. About 8% of people admitted to hospitals for other reasons in San Francisco test positive for COVID without symptoms, which we can assume translates for other cities. That means many may think they're fine and they're actually infectious. The result is a much higher chance of someone getting many other people sick.

During this time of record-breaking cases, you need to be mindful about your internalized assumptions and adjust your risk calculus accordingly. So if you can delay higher-risk activities, January and February might be the time to do it. Prepare for waves of disruptions to continue over time, at least through the end of February.

Of course, you might also choose to not worry about getting infected. If you are vaccinated and boosted, and do not have any additional health risks, you are very unlikely to have a serious illness due to Omicron. You can just take the small risk of a serious illness – which can happen – and go about your daily life. If doing so, watch out for those you care about who do have health concerns, since if you infect them, they might not have a mild case even with Omicron.

In short, instead of trying to turn back the clock to the lost world of January 2020, consider how we might create a competitive advantage in our new future. COVID will never go away: we need to learn to live with it. That means reacting appropriately and thoughtfully to new variants and being intentional about our trade-offs.