Carl Zimmer: Genetically Editing Humans Should Not Be Our Biggest Worry

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

The award-winning New York Times science writer Carl Zimmer.

Carl Zimmer, the award-winning New York Times science writer, recently published a stellar book about human heredity called "She Has Her Mother's Laugh." Truly a magnum opus, the book delves into the cultural and scientific evolution of genetics, the field's outsize impact on society, and the new ways we might fundamentally alter our species and our planet.

"I was only prepared to write about how someday we would cross this line, and actually, we've already crossed it."

Zimmer spoke last week with editor-in-chief Kira Peikoff about the international race to edit the genes of human embryos, the biggest danger he sees for society (hint: it's not super geniuses created by CRISPR), and some outlandish possibilities for how we might reproduce in the future. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I was struck by the number of surprises you uncovered while researching human heredity, like how fetal cells can endure for a lifetime in a mother's body and brain. What was one of the biggest surprises for you?

Something that really jumped out for me was for the section on genetically modifying people. It does seem incredibly hypothetical. But then I started looking into mitochondrial replacement therapy, so-called "three parent babies." I was really surprised to discover that almost by accident, a number of genetically modified people were created this way [in the late 90s and early 2000s]. They walk among us, and they're actually fine as far as anyone can tell. I was only prepared to write about how someday we would cross this line, and actually, we've already crossed it.

And now we have the current arms race between the U.S. and China to edit diseases out of human embryos, with China being much more willing and the U.S. more reluctant. Do you think it's more important to get ahead or to proceed as ethically as possible?

I would prefer a middle road. I think that rushing into tinkering with the features of human heredity could be a disastrous mistake for a lot of reasons. On the other hand, if we completely retreat from it out of some vague fear, I think that we won't take advantage of the actual benefits that this technology might have that are totally ethically sound.

I think the United Kingdom is actually showing how you can go the middle route with mitochondrial replacement therapy. The United States has just said nope, you can't do it at all, and you have Congressmen talking about how it's just playing God or Frankenstein. And then there are countries like Mexico or the Ukraine where people are doing mitochondrial replacement therapy because there are no regulations at all. It's a wild west situation, and that's not a good idea either.

But in the UK, they said alright, well let's talk about this, let's have a debate in Parliament, and they did, and then the government came up with a well thought-through policy. They decided that they were going to allow for this, but only in places that applied for a license, and would be monitored, and would keep track of the procedure and the health of these children and actually have real data going forward. I would imagine that they're going to very soon have their first patients.

As you mentioned, one researcher recently traveled to Mexico from New York to carry out the so-called "three-parent baby" procedure in order to escape the FDA's rules. What's your take on scientists having to leave their own jurisdictions to advance their research programs under less scrutiny?

I think it's a problem when people who have a real medical need have to leave their own country to get truly effective treatment for it. On the other hand, we're seeing lots of people going abroad to countries that don't monitor all the claims that clinics are making about their treatments. So you have stem cell clinics in all sorts of places that are making all sorts of ridiculous promises. They're not delivering those results, and in some cases, they're doing harm.

"Advances in stem cell biology and reproductive biology are a much bigger challenge to our conventional ideas about heredity than CRISPR is."

It's a tricky tension for sure. Speaking of gene editing humans, you mention in the book that one of the CRISPR pioneers, Jennifer Doudna, now has recurring nightmares about Hitler. Do you think that her fears about eugenics being revived with gene editing are justified?

The word "eugenics" has a long history and it's meant different things to different people. So we have to do a better job of talking about it in the future if we really want to talk about the risks and the promises of technology like CRISPR. Eugenics in its most toxic form was an ideology that let governments, including the United States, sterilize their own citizens by the tens of thousands. Then Nazi Germany also used eugenics as a justification to exterminate many more people.

Nobody's talking about that with CRISPR. Now, are people concerned that we are going to wipe out lots of human genetic diversity with it? That would be a bad thing, but I'm skeptical that would actually ever happen. You would have to have some sort of science fiction one-world government that required every new child to be born with IVF. It's not something that keeps me up at night. Honestly, I think we have much bigger problems to worry about.

What is the biggest danger relating to genetics that we should be aware of?

Part of what made eugenics such a toxic ideology was that it was used as a justification for indifference. In other words, if there are problems in society, like a large swath of people who are living in poverty, well, there's nothing you can do about it because it must be due to genetics.

If you look at genetics as being the sole place where you can solve humanity's problems, then you're going to say well, there's no point in trying to clean up the environment or trying to improve human welfare.

A major theme in your book is that we should not narrow our focus on genes as the only type of heredity. We also may inherit some epigenetic marks, some of our mother's microbiome and mitochondria, and importantly, our culture and our environment. Why does an expanded view of heredity matter?

We should think about the world that our children are going to inherit, and their children, and their children. They're going to inherit our genes, but they're also going to inherit this planet and we're doing things that are going to have an incredibly long-lasting impact on it. I think global warming is one of the biggest. When you put carbon dioxide into the air, it stays there for a very, very long time. If we stopped emitting carbon dioxide now, the Earth would stay warm for many centuries. We should think about tinkering with the future of genetic heredity, but I think we should also be doing that with our environmental heredity and our cultural heredity.

At the end of the book, you discuss some very bizarre possibilities for inheritance that could be made possible through induced pluripotent stem cell technology and IVF -- like four-parent babies, men producing eggs, and children with 8-celled embryos as their parents. If this is where reproductive medicine is headed, how can ethics keep up?

I'm not sure actually. I think that these advances in stem cell biology and reproductive biology are a much bigger challenge to our conventional ideas about heredity than CRISPR is. With CRISPR, you might be tweaking a gene here and there, but they're still genes in an embryo which then becomes a person, who would then have children -- the process our species has been familiar with for a long time.

"We have to recognize that we need a new language that fits with the science of heredity in the 21st century."

We all assume that there's no way to find a fundamentally different way of passing down genes, but it turns out that it's not really that hard to turn a skin cell from a cheek scraping into an egg or sperm. There are some challenges that still have to be worked out to make this something that could be carried out a lot in labs, but I don't see any huge barriers to it. Ethics doesn't even have the language to discuss the possibilities. Like for example, one person producing both male and female sex cells, which are then fertilized to produce embryos so that you have a child who only has one parent. How do we even talk about that? I don't know. But that's coming up fast.

We haven't developed our language as quickly as the technology itself. So how do we move forward?

We have to recognize that we need a new language that fits with the science of heredity in the 21st century. I think one of the biggest problems we have as a society is that most of our understanding about these issues largely comes from what we learned in grade school and high school in biology class. A high school biology class, even now, gets up to Mendel and then stops. Gregor Mendel is a great place to start, but it's a really bad place to stop talking about heredity.

[Ed. Note: Zimmer's book can be purchased through your retailer of choice here.]

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

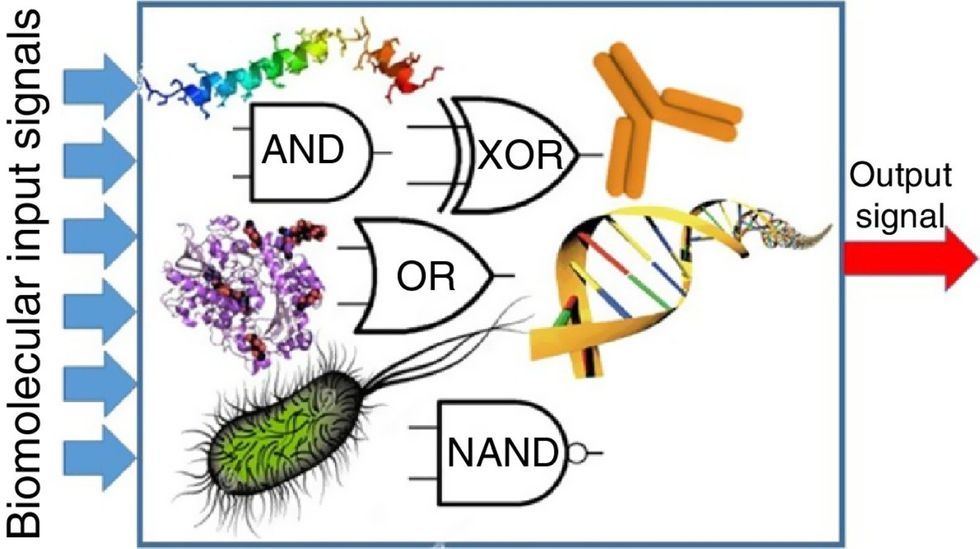

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.