How dozens of men across Alaska (and their dogs) teamed up to save one town from a deadly outbreak

In 1925, health officials in Alaska came up with a creative solution to save a remote fishing town from a deadly disease outbreak.

During the winter of 1924, Curtis Welch – the only doctor in Nome, a remote fishing town in northwest Alaska – started noticing something strange. More and more, the children of Nome were coming to his office with sore throats.

Initially, Welch dismissed the cases as tonsillitis or some run-of-the-mill virus – but when more kids started getting sick, with some even dying, he grew alarmed. It wasn’t until early 1925, after a three-year-old boy died just two weeks after becoming ill, that Welch realized that his worst suspicions were true. The boy – and dozens of other children in town – were infected with diphtheria.

A DEADLY BACTERIA

Diphtheria is nearly nonexistent and almost unheard of in industrialized countries today. But less than a century ago, diphtheria was a household name – one that struck fear in the heart of every parent, as it was extremely contagious and particularly deadly for children.

Diphtheria – a bacterial infection – is an ugly disease. When it strikes, the bacteria eats away at the healthy tissues in a patient’s respiratory tract, leaving behind a thick, gray membrane of dead tissue that covers the patient's nose, throat, and tonsils. Not only does this membrane make it very difficult for the patient to breathe and swallow, but as the bacteria spreads through the bloodstream, it causes serious harm to the heart and kidneys. It sometimes also results in nerve damage and paralysis. Even with treatment, diphtheria kills around 10 percent of people it infects. Young children, as well as adults over the age of 60, are especially at risk.

Welch didn’t suspect diphtheria at first. He knew the illness was incredibly contagious and reasoned that many more people would be sick – specifically, the family members of the children who had died – if there truly was an outbreak. Nevertheless, the symptoms, along with the growing number of deaths, were unmistakable. By 1925 Welch knew for certain that diphtheria had come to Nome.

In desperation, Welch tried treating an infected seven-year-old girl with some expired antitoxin – but she died just a few hours after he administered it.

AN INACCESSIBLE CURE

A vaccine for diphtheria wouldn’t be widely available until the mid-1930s and early 1940s – so an outbreak of the disease meant that each of the 10,000 inhabitants of Nome were all at serious risk.

One option was to use something called an antitoxin – a serum consisting of anti-diphtheria antibodies – to treat the patients. However, the town’s reserve of diphtheria antitoxin had expired. Welch had ordered a replacement shipment of antitoxin the previous summer – but the shipping port that was set to deliver the serum had been closed due to ice, and no new antitoxin would arrive before spring of 1925. In desperation, Welch tried treating an infected seven-year-old girl with some expired antitoxin – but she died just a few hours after he administered it.

Welch radioed for help to all the major towns in Alaska as well as the US Public Health Service in Washington, DC. His telegram read: An outbreak of diphtheria is almost inevitable here. I am in urgent need of one million units of diphtheria antitoxin. Mail is the only form of transportation.

FOUR-LEGGED HEROES

When the Alaskan Board of Health learned about the outbreak, the men rushed to devise a plan to get antitoxin to Nome. Dropping the serum in by airplane was impossible, as the available planes were unsuitable for flying during Alaska’s severe winter weather, where temperatures were routinely as cold as -50 degrees Fahrenheit.

In late January 1925, roughly 30,000 units of antitoxin were located in an Anchorage hospital and immediately delivered by train to a nearby city, Nenana, en route to Nome. Nenana was the furthest city that was reachable by rail – but unfortunately it was still more than 600 miles outside of Nome, with no transportation to make the delivery. Meanwhile, Welch had confirmed 20 total cases of diphtheria, with dozens more at high risk. Diphtheria was known for wiping out entire communities, and the entire town of Nome was in danger of suffering the same fate.

It was Mark Summer, the Board of Health superintendent, who suggested something unorthodox: Using a relay team of sled-racing dogs to deliver the antitoxin serum from Nenana to Nome. The Board quickly voted to accept Summer’s idea and set up a plan: The thousands of units of antitoxin serum would be passed along from team to team at different towns along the mail route from Nenana to Nome. When it reached a town called Nulato, a famed dogsled racer named Leonhard Seppala and his experienced team of huskies would take the serum more than 90 miles over the ice of Norton Sound, the longest and most treacherous part of the journey. Past the sound, the serum would change hands several times more before arriving in Nome.

Between January 27 and 31, the serum passed through roughly a dozen drivers and their dog sled teams, each of them carrying the serum between 20 and 50 miles to the next destination. Though each leg of the trip took less than a day, the sub-zero temperatures – sometimes as low as -85 degrees – meant that every driver and dog risked their lives. When the first driver, Bill Shannon, arrived at his checkpoint in Tolovana on January 28th, his nose was black with frostbite, and three of his dogs had died. The driver who relieved Bill Shannon, named Edgar Kalland, needed the owner of a local roadhouse to pour hot water over his hands to free them from the sled’s metal handlebar. Two more dogs from another relay team died before the serum was passed to Seppala at a town called Ungalik.

THE FINAL STRETCHES

Seppala and his team raced across the ice of the Norton Sound in the dead of night on January 31, with wind chill temperatures nearing an astonishing -90 degrees. The team traveled 84 miles in a single day before stopping to rest – and once rested, they set off again in the middle of the night through a raging winter storm. The team made it across the ice, as well as a 5,000-foot ascent up Little McKinley Mountain, to pass the serum to another driver in record time. The serum was now just 78 miles from Nome, and the death toll in town had reached 28.

The serum reached Gunnar Kaasen and his team of dogs on February 1st. Balto, Kaasen’s lead dog, guided the team heroically through a winter storm that was so severe Kaasen later reported not being able to see the dogs that were just a few feet ahead of him.

Visibility was so poor, in fact, that Kaasen ran his sled two miles past the relay point before noticing – and not wanting to lose a minute, he decided to forge on ahead rather than doubling back to deliver the serum to another driver. As they continued through the storm, the hurricane-force winds ripped past Kaasen’s sled at one point and toppled the sled – and the serum – overboard. The cylinder containing the antitoxin was left buried in the snow – and Kaasen tore off his gloves and dug through the tundra to locate it. Though it resulted in a bad case of frostbite, Kaasen eventually found the cylinder and kept driving.

Kaasen arrived at the next relay point on February 2nd, hours ahead of schedule. When he got there, however, he found the relay driver of the next team asleep. Kaasen took a risk and decided not to wake him, fearing that time would be wasted with the next driver readying his team. Kaasen, Balto, and the rest of the team forged on, driving another 25 miles before finally reaching Nome just before six in the morning. Eyewitnesses described Kaasen pulling up to the town’s bank and stumbling to the front of the sled. There, he collapsed in exhaustion, telling onlookers that Balto was “a damn fine dog.”

A LIVING LEGACY

Just a few hours after Balto’s heroic arrival in Nome, the serum had been thawed and was ready to administer to the patients with diphtheria. Amazingly, the relay team managed to complete the entire journey in just 127 hours – a world record at the time – without one serum vial damaged or destroyed. The serum shipment that arrived by dogsled – along with additional serum deliveries that followed in the next several weeks – were successful in stopping the outbreak in its tracks.

Balto and several other dogs – including Togo, the lead dog on Seppala’s team – were celebrated as local heroes after the race. Balto died in 1933, while the last of the human serum runners died in 1999 – but their legacy lives on: In early 2021, an all-female team of healthcare workers made the news by braving the Alaskan winter to deliver COVID-19 vaccines to people in rural North Alaska, traveling by bobsled and snowmobile – a heroic journey, and one that would have been unthinkable had Balto, Togo, and the 1925 sled runners not first paved the way.

Three Big Biotech Ideas to Watch in 2020—And Beyond

Body-on-a-chip, prime editing, and gut microbes all are poised to make a big impact in 2020.

1. Happening Now: Body-on-a-Chip Technology Is Enabling Safer Drug Trials and Better Cancer Research

Researchers have increasingly used the technology known as "lab-on-a-chip" or "organ-on-a-chip" to test the effects of pharmaceuticals, toxins, and chemicals on humans. Rather than testing on animals, which raises ethical concerns and can sometimes be inaccurate, and human-based clinical trials, which can be expensive and difficult to iterate, scientists turn to tiny, micro-engineered chips—about the size of a thumb drive.

It's possible that doctors could one day take individual cell samples and create personalized treatments, testing out any medications on the chip.

The chips are lined with living samples of human cells, which mimic the physiology and mechanical forces experienced by cells inside the human body, down to blood flow and breathing motions; the functions of organs ranging from kidneys and lungs to skin, eyes, and the blood-brain barrier.

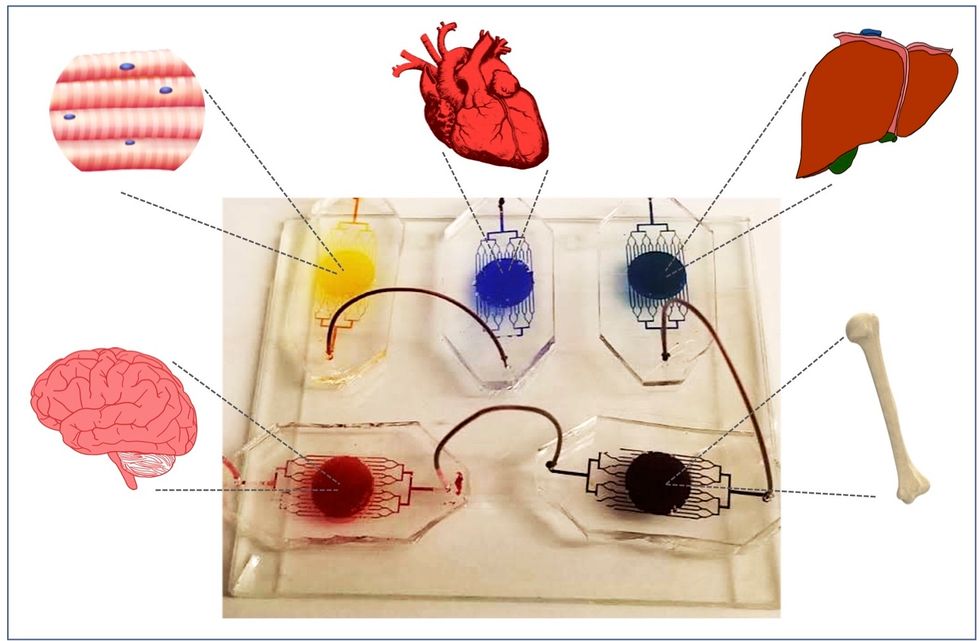

A more recent—and potentially even more useful—development takes organ-on-a-chip technology to the next level by integrating several chips into a "body-on-a-chip." Since human organs don't work in isolation, seeing how they all react—and interact—once a foreign element has been introduced can be crucial to understanding how a certain treatment will or won't perform. Dr. Shyni Varghese, a MEDx investigator at the Duke University School of Medicine, is one of the researchers working with these systems in order to gain a more nuanced understanding of how multiple different organs react to the same stimuli.

Her lab is working on "tumor-on-a-chip" models, which can not only show the progression and treatment of cancer, but also model how other organs would react to immunotherapy and other drugs. "The effect of drugs on different organs can be tested to identify potential side effects," Varghese says. In addition, these models can help the researchers figure out how cancers grow and spread, as well as how to effectively encourage immune cells to move in and attack a tumor.

One body-on-a-chip used by Dr. Varghese's lab tracks the interactions of five organs—brain, heart, liver, muscle, and bone.

As their research progresses, Varghese and her team are looking for ways to maintain the long-term function of the engineered organs. In addition, she notes that this kind of research is not just useful for generalized testing; "organ-on-chip technologies allow patient-specific analyses, which can be used towards a fundamental understanding of disease progression," Varghese says. It's possible that doctors could one day take individual cell samples and create personalized treatments, testing out any medications on the chip for safety, efficacy, and potential side effects before writing a prescription.

2. Happening Soon: Prime Editing Will Have the Power to "Find and Replace" Disease-Causing Genes

Biochemist David Liu made industry-wide news last fall when he and his lab at MIT's Broad Institute, led by Andrew Anzalone, published a paper on prime editing: a new, more focused technology for editing genes. Prime editing is a descendant of the CRISPR-Cas9 system that researchers have been working with for years, and a cousin to Liu's previous innovation—base editing, which can make a limited number of changes to a single DNA letter at a time.

By contrast, prime editing has the potential to make much larger insertions and deletions; it also doesn't require the tweaked cells to divide in order to write the changes into the DNA, which could make it especially suitable for central nervous system diseases, like Parkinson's.

Crucially, the prime editing technique has a much higher efficiency rate than the older CRISPR system, and a much lower incidence of accidental insertions or deletions, which can make dangerous changes for a patient.

It also has a very broad potential range: according to Liu, 89% of the pathogenic mutations that have been collected in ClinVar (a public archive of human variations) could, in principle, be treated with prime editing—although he is careful to note that correcting a single genetic mutation may not be sufficient to fully treat a genetic disease.

Figuring out just how prime editing can be used most effectively and safely will be a long process, but it's already underway. The same day that Liu and his team posted their paper, they also made the basic prime editing constructs available for researchers around the world through Addgene, a plasmid repository, so that others in the scientific community can test out the technique for themselves. It might be years before human patients will see the results, and in the meantime, significant bioethical questions remain about the limits and sociological effects of such a powerful gene-editing tool. But in the long fight against genetic diseases, it's a huge step forward.

3. Happening When We Fund It: Focusing on Microbiome Health Could Help Us Tackle Social Inequality—And Vice Versa

The past decade has seen a growing awareness of the major role that the microbiome, the microbes present in our digestive tract, play in human health. Having a less-healthy microbiome is correlated with health risks like diabetes and depression, and interventions that target gut health, ranging from kombucha to fecal transplants, have cropped up with increasing frequency.

New research from the University of Maine's Dr. Suzanne Ishaq takes an even broader view, arguing that low-income and disadvantaged populations are less likely to have healthy, diverse gut bacteria, and that increasing access to beneficial microorganisms is an important juncture of social justice and public health.

"Basically, allowing people to lead healthy lives allows them to access and recruit microbes."

"Typically, having a more diverse bacterial community is associated with health, and having fewer different species is associated with illness and may leave you open to infection from bacteria that are good at exploiting opportunities," Ishaq says.

Having a healthy biome doesn't mean meeting one fixed ratio of gut bacteria, since different combinations of microbes can generate roughly similar results when they work in concert. Generally, "good" microbes are the ones that break down fiber and create the byproducts that we use for energy, or ones like lactic acid bacteria that work to make microbials and keep other bacteria in check. The microbial universe in your gut is chaotic, Ishaq says. "Microbes in your gut interact with each other, with you, with your food, or maybe they don't interact at all and pass right through you." Overall, it's tricky to name specific microbial communities that will make or break someone's health.

There are important corollaries between environment and biome health, though, which Ishaq points out: Living in urban environments reduces microbial exposure, and losing the microorganisms that humans typically source from soil and plants can reduce our adaptive immunity and ability to fight off conditions like allergies and asthma. Access to green space within cities can counteract those effects, but in the U.S. that access varies along income, education, and racial lines. Likewise, lower-income communities are more likely to live in food deserts or areas where the cheapest, most convenient food options are monotonous and low in fiber, further reducing microbial diversity.

Ishaq also suggests other areas that would benefit from further study, like the correlation between paid family leave, breastfeeding, and gut microbiota. There are technical and ethical challenges to direct experimentation with human populations—but that's not what Ishaq sees as the main impediment to future research.

"The biggest roadblock is money, and the solution is also money," she says. "Basically, allowing people to lead healthy lives allows them to access and recruit microbes."

That means investment in things we already understand to improve public health, like better education and healthcare, green space, and nutritious food. It also means funding ambitious, interdisciplinary research that will investigate the connections between urban infrastructure, housing policy, social equity, and the millions of microbes keeping us company day in and day out.

Scientists Just Started Testing a New Class of Drugs to Slow--and Even Reverse--Aging

Eliminating "zombie-like" cells, called senescent cells, may hold the key to slowing aging and its chronic diseases.

Imagine reversing the processes of aging. It's an age-old quest, and now a study from the Mayo Clinic may be the first ray of light in the dawn of that new era.

The immune system can handle a certain amount of senescence, but that capacity declines with age.

The small preliminary report, just nine patients, primarily looked at the safety and tolerability of the compounds used. But it also showed that a new class of small molecules called senolytics, which has proven to reverse markers of aging in animal studies, can work in humans.

Aging is a relentless assault of chronic diseases including Alzheimer's, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and frailty. Developing one chronic condition strongly predicts the rapid onset of another. They pile on top of each other and impede the body's ability to respond to the next challenge.

"Potentially, by targeting fundamental aging processes, it may be possible to delay or prevent or alleviate multiple age-related conditions and many diseases as a group, instead of one at a time," says James Kirkland, the Mayo Clinic physician who led the study and is a top researcher in the growing field of geroscience, the biology of aging.

Getting Rid of "Zombie" Cells

One element common to many of the diseases is senescence, a kind of limbo or zombie-like state where cells no longer divide or perform many regular functions, but they don't die. Senescence is thought to be beneficial in that it inhibits the cancerous proliferation of cells. But in aging, the senescent cells still produce molecules that create inflammation both locally and throughout the body. It is a cycle that feeds upon itself, slowly ratcheting down normal body function and health.

Disease and harmful stimuli like radiation to treat cancer can also generate senescence, which is why young cancer patients seem to experience earlier and more rapid aging. The immune system can handle a certain amount of senescence, but that capacity declines with age. There also appears to be a threshold effect, a tipping point where senescence becomes a dominant factor in aging.

Kirkland's team used an artificial intelligence approach called machine learning to look for cell signaling networks that keep senescent cells from dying. To date, researchers have identified at least eight such signaling networks, some of which seem to be unique to a particular type of cell or tissue, but others are shared or overlap.

Then a computer search identified molecules known to disrupt these signaling pathways "and allow cells that are fully senescent to kill themselves," he explains. The process is a bit like looking for the right weapons in a video game to wipe out lingering zombie cells. But instead of swords, guns, and grenades, the list of biological tools so far includes experimental molecules, approved drugs, and natural supplements.

Treatment

"We found early on that targeting single components of those networks will only kill a very small minority of senescent cells or senescent cell types," says Kirkland. "So instead of going after one drug-one target-one disease, we're going after networks with combinations of drugs or drugs that have multiple targets. And we're going after every age-related disease."

The FDA is grappling with guidance for researchers wanting to conduct clinical trials on something as broad as aging rather than a single disease.

The large number of potential senolytic (i.e. zombie-neutralizing) compounds they identified allowed Kirkland to be choosy, "purposefully selecting drugs where the side effects profile was good...and with short elimination half-lives." The hit and run approach meant they didn't have to worry about maintaining a steady state of drugs in the body for an extended period of time. Some of the compounds they selected need only a half hour exposure to trigger the dying process in senescent cells, which can then take several days.

Work in mice has already shown impressive results in reversing diabetes, weight gain, Alzheimer's, cardiovascular disease and other conditions using senolytic agents.

That led to Kirkland's pilot study in humans with diabetes-related kidney disease using a three-day regimen of dasatinib, a kinase inhibitor first approved in 2006 to treat some forms of blood cancer, and quercetin, a flavonoid found in many plants and sold as a food supplement.

The combination was safe and well tolerated; it reduced the number of senescent cells in the belly fat of patients and restored their normal function, according to results published in September in the journal EBioMedicine. This preliminary paper was based on 9 patients in an ongoing study of 30 patients.

Kirkland cautions that these are initial and incomplete findings looking primarily at safety issues, not effectiveness. There is still much to be learned about the use of senolytics, starting with proof that they actually provide clinical benefit, and against what chronic conditions. The drug combinations, doses, duration, and frequency, not to mention potential risks all must be worked out. Additional studies of other diseases are being developed.

What's Next

Ron Kohanski, a senior administrator at the NIH National Institute on Aging (NIA), says the field of senolytics is so new that there isn't even a consensus on how to identify a senescent cell, and the FDA is grappling with guidance for researchers wanting to conduct clinical trials on something as broad as aging rather than a single disease.

Intellectual property concerns may temper the pharmaceutical industry's interest in developing senolytics to treat chronic diseases of aging. It looks like many mix-and-match combinations are possible, and many of the potential molecules identified so far are found in nature or are drugs whose patents have or will soon expire. So the ability to set high prices for such future drugs, and hence the willingness to spend money on expensive clinical trials, may be limited.

Still, Kohanski believes the field can move forward quickly because it often will include products that are already widely used and have a known safety profile. And approaches like Kirkland's hit and run strategy will minimize potential exposure and risk.

He says the NIA is going to support a number of clinical trials using these new approaches. Pharmaceutical companies may feel that they can develop a unique part of a senolytic combination regimen that will justify their investment. And if they don't, countries with socialized medicine may take the lead in supporting such research with the goal of reducing the costs of treating aging patients.