Scientists Are Growing an Edible Cholera Vaccine in Rice

The world's attention has been focused on the coronavirus crisis but Yemen, Bangladesh and many others countries in Asia and Africa are also in the grips of another pandemic: cholera. The current cholera pandemic first emerged in the 1970s and has devastated many communities in low-income countries. Each year, cholera is responsible for an estimated 1.3 million to 4 million cases and 21,000 to 143,000 deaths worldwide.

Immunologist Hiroshi Kiyono and his team at the University of Tokyo hope they can be part of the solution: They're making a cholera vaccine out of rice.

"It is much less expensive than a traditional vaccine, by a long shot."

Cholera is caused by eating food or drinking water that's contaminated by the feces of a person infected with the cholera bacteria, Vibrio cholerae. The bacteria produces the cholera toxin in the intestines, leading to vomiting, diarrhea and severe dehydration. Cholera can kill within hours of infection if it if's not treated quickly.

Current cholera vaccines are mainly oral. The most common oral are given in two doses and are made out of animal or insect cells that are infected with killed or weakened cholera bacteria. Dukoral also includes cells infected with CTB, a non-harmful part of the cholera toxin. Scientists grow cells containing the cholera bacteria and the CTB in bioreactors, large tanks in which conditions can be carefully controlled.

These cholera vaccines offer moderate protection but it wears off relatively quickly. Cold storage can also be an issue. The most common oral vaccines can be stored at room temperature but only for 14 days.

"Current vaccines confer around 60% efficacy over five years post-vaccination," says Lucy Breakwell, who leads the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's cholera work within Global Immunization Division. Given the limited protection, refrigeration issue, and the fact that current oral vaccines require two disease, delivery of cholera vaccines in a campaign or emergency setting can be challenging. "There is a need to develop and test new vaccines to improve public health response to cholera outbreaks."

A New Kind of Vaccine

Kiyono and scientists at Tokyo University are creating a new, plant-based cholera vaccine dubbed MucoRice-CTB. The researchers genetically modify rice so that it contains CTB, a non-harmful part of the cholera toxin. The rice is crushed into a powder, mixed with saline solution and then drunk. The digestive tract is lined with mucosal membranes which contain the mucosal immune system. The mucosal immune system gets trained to recognize the cholera toxin as the rice passes through the intestines.

The cholera toxin has two main parts: the A subunit, which is harmful, and the B subunit, also known as CTB, which is nontoxic but allows the cholera bacteria to attach to gut cells. By inducing CTB-specific antibodies, "we might be able to block the binding of the vaccine toxin to gut cells, leading to the prevention of the toxin causing diarrhea," Kiyono says.

Kiyono studies the immune responses that occur at mucosal membranes across the body. He chose to focus on cholera because he wanted to replicate the way traditional vaccines work to get mucosal membranes in the digestive tract to produce an immune response. The difference is that his team is creating a food-based vaccine to induce this immune response. They are also solely focusing on getting the vaccine to induce antibodies for the cholera toxin. Since the cholera toxin is responsible for bacteria sticking to gut cells, the hope is that they can stop this process by producing antibodies for the cholera toxin. Current cholera vaccines target the cholera bacteria or both the bacteria and the toxin.

David Pascual, an expert in infectious diseases and immunology at the University of Florida, thinks that the MucoRice vaccine has huge promise. "I truly believe that the development of a food-based vaccine can be effective. CTB has a natural affinity for sampling cells in the gut to adhere, be processed, and then stimulate our immune system, he says. "In addition to vaccinating the gut, MucoRice has the potential to touch other mucosal surfaces in the mouth, which can help generate an immune response locally in the mouth and distally in the gut."

Cost Effectiveness

Kiyono says the MucoRice vaccine is much cheaper to produce than a traditional vaccine. Current vaccines need expensive bioreactors to grow cell cultures under very controlled, sterile conditions. This makes them expensive to manufacture, as different types of cell cultures need to be grown in separate buildings to avoid any chance of contamination. MucoRice doesn't require such an expensive manufacturing process because the rice plants themselves act as bioreactors.

The MucoRice vaccine also doesn't require the high cost of cold storage. It can be stored at room temperature for up to three years unlike traditional vaccines. "Plant-based vaccine development platforms present an exciting tool to reduce vaccine manufacturing costs, expand vaccine shelf life, and remove refrigeration requirements, all of which are factors that can limit vaccine supply and accessibility," Breakwell says.

Kathleen Hefferon, a microbiologist at Cornell University agrees. "It is much less expensive than a traditional vaccine, by a long shot," she says. "The fact that it is made in rice means the vaccine can be stored for long periods on the shelf, without losing its activity."

A plant-based vaccine may even be able to address vaccine hesitancy, which has become a growing problem in recent years. Hefferon suggests that "using well-known food plants may serve to reduce the anxiety of some vaccine hesitant people."

Challenges of Plant Vaccines

Despite their advantages, no plant-based vaccines have been commercialized for human use. There are a number of reasons for this, ranging from the potential for too much variation in plants to the lack of facilities large enough to grow crops that comply with good manufacturing practices. Several plant vaccines for diseases like HIV and COVID-19 are in development, but they're still in early stages.

In developing the MucoRice vaccine, scientists at the University of Tokyo have tried to overcome some of the problems with plant vaccines. They've created a closed facility where they can grow rice plants directly in nutrient-rich water rather than soil. This ensures they can grow crops all year round in a space that satisfies regulations. There's also less chance for variation since the environment is tightly controlled.

Clinical Trials and Beyond

After successfully growing rice plants containing the vaccine, the team carried out their first clinical trial. It was completed early this year. Thirty participants received a placebo and 30 received the vaccine. They were all Japanese men between the ages of 20 and 40 years old. 60 percent produced antibodies against the cholera toxin with no side effects. It was a promising result. However, there are still some issues Kiyono's team need to address.

The vaccine may not provide enough protection on its own. The antigen in any vaccine is the substance it contains to induce an immune response. For the MucoRice vaccine, the antigen is not the cholera bacteria itself but the cholera toxin the bacteria produces.

"The development of the antigen in rice is innovative," says David Sack, a professor at John Hopkins University and expert in cholera vaccine development. "But antibodies against only the toxin have not been very protective. The major protective antigen is thought to be the LPS." LPS, or lipopolysaccharide, is a component of the outer wall of the cholera bacteria that plays an important role in eliciting an immune response.

The Japanese team is considering getting the rice to also express the O antigen, a core part of the LPS. Further investigation and clinical trials will look into improving the vaccine's efficacy.

Beyond cholera, Kiyono hopes that the vaccine platform could one day be used to make cost-effective vaccines for other pathogens, such as norovirus or coronavirus.

"We believe the MucoRice system may become a new generation of vaccine production, storage, and delivery system."

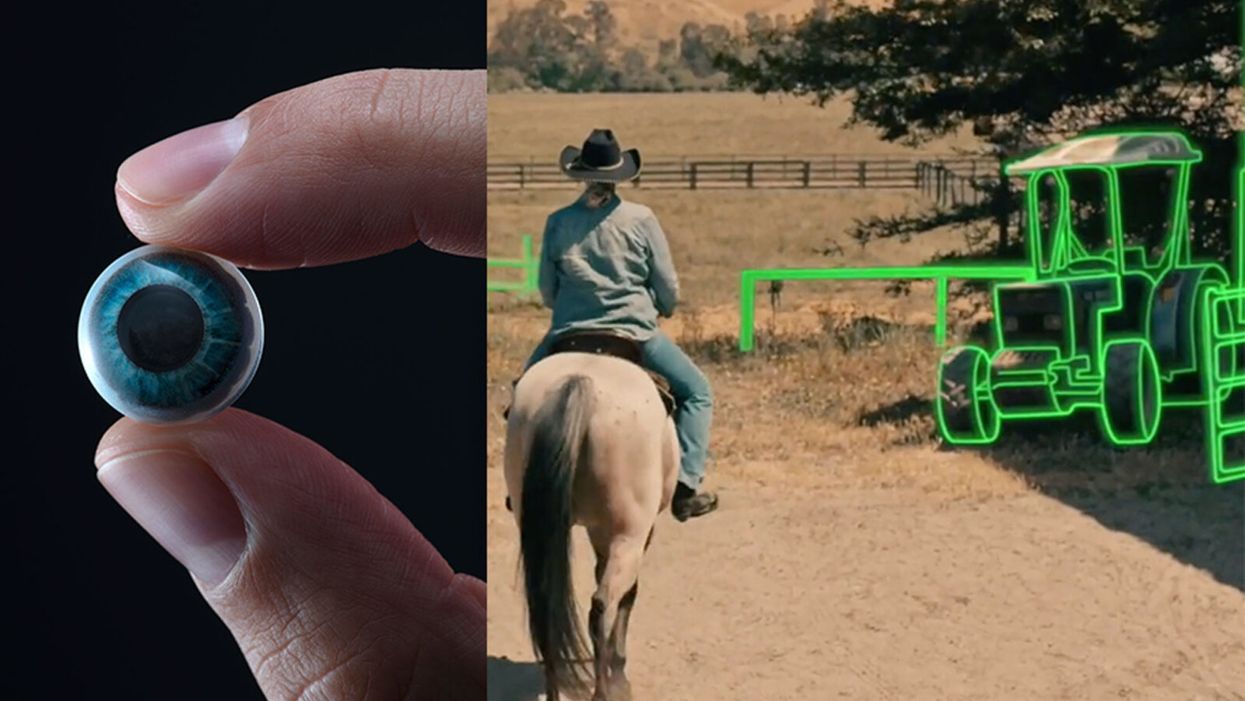

World’s First “Augmented Reality” Contact Lens Aims to Revolutionize Much More Than Medicine

On the left, a picture of the Mojo lens smart contact; and a simulated image of a woman with low vision who is wearing the contact to highlight objects in her field of vision.

Imagine a world without screens. Instead of endlessly staring at your computer or craning your neck down to scroll through social media feeds and emails, information simply appears in front of your eyes when you need it and disappears when you don't.

"The vision is super clear...I was reading the poem with my eyes closed."

No more rude interruptions during dinner, no more bumping into people on the street while trying to follow GPS directions — just the information you want, when you need it, projected directly onto your visual field.

While this screenless future sounds like science fiction, it may soon be a reality thanks to the new Silicon Valley startup Mojo Vision, creator of the world's first smart contact lens. With a 14,000 pixel-per-inch display with eye-tracking, image stabilization, and a custom wireless radio, the Mojo smart lens bills itself the "smallest and densest dynamic display ever made." Unlike current augmented reality wearables such as Google Glass or ThirdEye, which project images onto a glass screen, the Mojo smart lens can project images directly onto the retina.

A current prototype displayed at the Consumer Electronics Show earlier this year in Las Vegas includes a tiny screen positioned right above the most sensitive area of the pupil. "[The Mojo lens] is a contact lens that essentially has wireless power and data transmission for a small micro LED projector that is placed over the center of the eye," explains David Hobbs, Director of Product Management at Mojo Vision. "[It] displays critical heads-up information when you need it and fades into the background when you're ready to continue on with your day."

Eventually, Mojo Visions' technology could replace our beloved smart devices but the first generation of the Mojo smart lens will be used to help the 2.2 billion people globally who suffer from vision impairment.

"If you think of the eye as a camera [for the visually impaired], the sensors are not working properly," explains Dr. Ashley Tuan, Vice President of Medical Devices at Mojo Vision and fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. "For this population, our lens can process the image so the contrast can be enhanced, we can make the image larger, magnify it so that low-vision people can see it or we can make it smaller so they can check their environment." In January of this year, the FDA granted Breakthrough Device Designation to Mojo, allowing them to have early and frequent discussions with the FDA about technical, safety and efficacy topics before clinical trials can be done and certification granted.

For now, Dr. Tuan is one of the few people who has actually worn the Mojo lens. "I put the contact lens on my eye. It was very comfortable like any contact lenses I've worn before," she describes. "The vision is super clear and then when I put on the accessories, suddenly I see Yoda in front of me and I see my vital signs. And then I have my colleague that prepared a beautiful poem that I loved when I was young [and] I was reading the poem with my eyes closed."

At the moment, there are several electronic glasses on the market like Acesight and Nueyes Pro that provide similar solutions for those suffering from visual impairment, but they are large, cumbersome, and highly visible. Mojo lens would be a discreet, more comfortable alternative that offers users more freedom of movement and independence.

"In the case of augmented-reality contact lenses, there could be an opportunity to improve the lives of people with low vision," says Dr. Thomas Steinemann, spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology and professor of ophthalmology at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland. "There are existing tools for people currently living with low vision—such as digital apps, magnifiers, etc.— but something wearable could provide more flexibility and significantly more aid in day-to-day tasks."

As one of the first examples of "invisible computing," the potential applications of Mojo lens in the medical field are endless.

According to Dr. Tuan, the visually impaired often suffer from depression due to their lack of mobility and 70 percent of them are underemployed. "We hope that they can use this device to gain their mobility so they can get that social aspect back in their lives and then, eventually, employment," she explains. "That is our first and most important goal."

But helping those with low visual capabilities is only Mojo lens' first possible medical application; augmented reality is already being used in medicine and is poised to revolutionize the field in the coming decades. For example, Accuvein, a device that uses lasers to provide real-time images of veins, is widely used by nurses and doctors to help with the insertion of needles for IVs and blood tests.

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, augmentation of reality has been used in surgery for many years with surgeons using devices such as Google Glass to overlay critical information about their patients into their visual field. Using software like the Holographic Navigation Platform by Scopsis, surgeons can see a mixed-reality overlay that can "show you complicated tumor boundaries, assist with implant placements and guide you along anatomical pathways," its developers say.

However, according to Dr. Tuan, augmented reality headsets have drawbacks in the surgical setting. "The advantage of [Mojo lens] is you don't need to worry about sweating or that the headset or glasses will slide down to your nose," she explains "Also, our lens is designed so that it will understand your intent, so when you don't want the image overlay it will disappear, it will not block your visual field, and when you need it, it will come back at the right time."

As one of the first examples of "invisible computing," the potential applications of Mojo lens in the medical field are endless. Possibilities include live translation of sign language for deaf people; helping those with autism to read emotions; and improving doctors' bedside manner by allowing them to fully engage with patients without relying on a computer.

"[By] monitoring those blood vessels we can [track] chronic disease progression: high blood pressure, diabetes, and Alzheimer's."

Furthermore, the lens could be used to monitor health issues. "We have image sensors in the lens right now that point to the world but we can have a camera pointing inside of your eye to your retina," says Dr. Tuan, "[By] monitoring those blood vessels we can [track] chronic disease progression: high blood pressure, diabetes, and Alzheimer's."

For the moment, the future medical applications of the Mojo lens are still theoretical, but the team is confident they can eventually become a reality after going through the proper regulatory review. The company is still in the process of design, prototype and testing of the lens, so they don't know exactly when it will be available for use, but they anticipate shipping the first available products in the next couple of years. Once it does go to market, it will be available by prescription only for those with visual impairments, but the team's goal is to bring it to broader consumer markets pending regulatory clearance.

"We see that right now there's a unique opportunity here for Mojo lens and invisible computing to help to shape what the next decade of technology development looks like," explains David Hobbs. "We can use [the Mojo lens] to better serve us as opposed to us serving technology better."

Schmidt Ocean Institute co-founder Wendy Schmidt is backed by 32 screens in research vessel Falkor's control room where most of the science takes place on the ship, from mapping to live streaming of underwater robotic dives.

WENDY SCHMIDT is a philanthropist and investor who has spent more than a dozen years creating innovative non-profit organizations to solve pressing global environmental and human rights issues. Recognizing the human dependence on sustaining and protecting our planet and its people, Wendy has built organizations that work to educate and advance an understanding of the critical interconnectivity between the land and the sea. Through a combination of grants and investments, Wendy's philanthropic work supports research and science, community organizations, promising leaders, and the development of innovative technologies. Wendy is president of The Schmidt Family Foundation, which she co-founded with her husband Eric in 2006. They also co-founded Schmidt Ocean Institute and Schmidt Futures.

Editors: The pandemic has altered the course of human history and the nature of our daily lives in equal measure. How has it affected the focus of your philanthropy across your organizations? Have any aspects of the crisis in particular been especially galvanizing as you considered where to concentrate your efforts?

Wendy: The COVID-19 pandemic has made the work of our philanthropy more relevant than ever. If anything, the circumstances of this time have validated the focus we have had for nearly 15 years. We support the need for universal access to clean, renewable energy, healthy food systems, and the dignity of human labor and self-determination in a world of interconnected living systems on land and in the Ocean we are only beginning to understand.

When you consider the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 virus on people who are poorly paid, poorly housed, with poor nutrition and health care, and exposed to unsafe conditions in the workplace—you see clearly how the systems that have been defining how we live, what we eat, who gets healthcare and what impacts the environment around us—need to change.

"This moment has propelled broad movements toward open publication and open sharing of data and samples—something that has always been a core belief in how we support and advance science."

If the pandemic teaches us anything, we learn what resilience looks like, and the essential role for local small businesses including restaurants, farms and ranches, dairies and fish markets in the long term vitality of communities. There is resonance, local economic benefit, and also accountability in these smaller systems, with shorter supply chains and less vertical integration.

The consolidation of vertically integrated business operations for the sake of global efficiency reveals its essential weakness when supply chains break down and the failure to encourage local economic centers leads to intense systemic disruption and the possibility of collapse.

Editors: For scientists, one significant challenge has been figuring out how to continue research, if at all, during this time of isolation and distancing. Yet, your research vessel Falkor, of the Schmidt Ocean Institute, is still on its expedition exploring the Coral Sea Marine Park in Australia—except now there are no scientists onboard. What was the vessel up to before the pandemic hit? Can you tell us more about how they are continuing to conduct research from afar now and how that's going?

Wendy: We have been extremely fortunate at Schmidt Ocean Institute. When the pandemic hit in March, our research vessel, Falkor, was already months into a year-long program to research unexplored deep sea canyons around Australia and at the Great Barrier Reef. We were at sea, with an Australian science group aboard, carrying on with our mission of exploration, discovery and communication, when we happened upon what we believe to be the world's longest animal—a siphonophore about 150 feet long, spiraling out at a depth of about 2100 feet at the end of a deeper dive in the Ningaloo Canyon off Western Australia. It was the kind of wondrous creature we find so often when we conduct ROV dives in the world's Ocean.

For more than two months this year, Falkor was reportedly the only research vessel in the world carrying on active research at sea. Once we were able to dock and return the science party to shore, we resumed our program at sea offering a scheduled set of now land-based scientists in lockdown in Australia the opportunity to conduct research remotely, taking advantage of the vessel's ship to shore communications, high resolution cameras and live streaming video. It's a whole new world, and quite wonderful in its own way.

Editors: Normally, 10–15 scientists would be aboard such a vessel. Is "remote research" via advanced video technology here to stay? Are there any upsides to this "new normal"?

Wendy: Like all things pandemic, remote research is an adaptation for what would normally occur. Since we are putting safety of the crew and guest scientists at the forefront, we're working to build strong remote connections between our crew, land based scientists and the many robotic tools on board Falkor. There's no substitute for in person work, but what we've developed during the current cruise is a pretty good and productive alternative in a crisis. And what's important is that this critical scientific research into the deep sea is able to continue, despite the pandemic on land.

Editors: Speaking of marine expeditions, you've sponsored two XPRIZE competitions focused on ocean health. Do you think challenge prizes could fill gaps of the global COVID-19 response, for example, to manufacture more testing kits, accelerate the delivery of PPE, or incentivize other areas of need?

Wendy: One challenge we are currently facing is that innovations don't have the funding pathway to scale, so promising ideas by entrepreneurs, researchers, and even major companies are being developed too slowly. Challenge prizes help raise awareness for problems we are trying to solve and attract new people to help solve those problems by giving them a pathway to contribute.

One idea might be for philanthropy to pair prizes and challenges with an "advanced market commitment" where the government commits to a purchase order for the innovation if it meets a certain test. That could be deeply impactful for areas like PPE and the production of testing kits.

Editors: COVID-19 testing, especially, has been sorely needed, here in the U.S. and in developing countries as well as low-income communities. That's why we're so intrigued by your Schmidt Science Fellows grantee Hal Holmes and his work to repurpose a new DNA technology to create a portable, mobile test for COVID-19. Can you tell us about that work and how you are supporting it?

Wendy: Our work with Conservation X Labs began years ago when our foundation was the first to support their efforts to develop a handheld DNA barcode sensor to help detect illegally imported and mislabeled seafood and timber products. The device was developed by Hal Holmes, who became one of our Schmidt Science Fellows and is the technical lead on the project, working closely with Conservation X Labs co-founders Alex Deghan and Paul Bunje. Now, with COVID-19, Hal and team have worked with another Schmidt Science Fellow, Fahim Farzardfard, to repurpose the technology—which requires no continuous power source, special training, or a lab—to serve as a mobile testing device for the virus.

The work is going very well, manufacturing is being organized, and distribution agreements with hospitals and government agencies are underway. You could see this device in use within a few months and have testing results within hours instead of days. It could be especially useful in low-income communities and developing countries where access to testing is challenging.

Editors: How is Schmidt Futures involved in the development of information platforms that will offer productive solutions?

Wendy: In addition to the work I've mentioned, we've also funded the development of tech-enabled tools that can help the medical community be better prepared for the ongoing spike of COVID cases. For example, we funded EdX and Learning Agency to develop an online training to help increase the number of medical professionals who can operate ventilators. The first course is being offered by Harvard University, and so far, over 220,000 medical professionals have enrolled. We have also invested in informational platforms that make it easier to contain the spread of the disease, such as our work with Recidiviz to model the impact of COVID-19 in prisons and outline policy steps states could take to limit the spread.

Information platforms can also play a big part pushing forward scientific research into the virus. For example, we've funded the UC Santa Cruz Virus Browser, which allows researchers to examine each piece of the virus and see the proteins it creates, the interactions in the host cell, and — most importantly — almost everything the recent scientific literature has to say about that stretch of the molecule.

Editors: The scale of research collaboration and the speed of innovation today seem unprecedented. The whole science world has turned its attention to combating the pandemic. What positive big-picture trends do you think or hope will persist once the crisis eventually abates?

Wendy: As in many areas, the COVID crisis has accelerated trends in the scientific world that were already well underway. For instance, this moment has propelled broad movements toward open publication and open sharing of data and samples—something that has always been a core belief in how we support and advance science.

We believe collaboration is an essential ingredient for progress in all areas. Early in this pandemic, Schmidt Futures held a virtual gathering of 160 people across 70 organizations in philanthropy, government, and business interested in accelerating research and response to the virus, and thought at the time, it's pretty amazing this kind of thing doesn't go all the time. We are obviously going to go farther together than on our own...

My husband, Eric, has observed that in the past two months, we've all catapulted 10 years forward in our use of technology, so there are trends already underway that are likely accelerated and will become part of the fabric of the post-COVID world—like working remotely; online learning; increased online shopping, even for groceries; telemedicine; increasing use of AI to create smarter delivery systems for healthcare and many other applications in a world that has grown more virtual overnight.

"Our deepest hope is that out of these alarming and uncertain times will come a renewed appreciation for the tools of science, as they help humans to navigate a world of interconnected living systems, of which viruses are a large part."

We fully expect these trends to continue and expand across the sciences, sped up by the pressures of the health crisis. Schmidt Ocean Institute and Schmidt Futures have been pressing in these directions for years, so we are pleased to see the expansions that should help more scientists work productively, together.

Editors: Trying to find the good amid a horrible crisis, are there any other new horizons in science, philanthropy, and/or your own work that could transform our world for the better that you'd like to share?

Wendy: Our deepest hope is that out of these alarming and uncertain times will come a renewed appreciation for the tools of science, as they help humans to navigate a world of interconnected living systems, of which viruses are a large part. The more we investigate the Ocean, the more we look deeply into what lies in our soils and beneath them, the more we realize we do not know, and moreover, how vulnerable humanity is to the forces of the natural world.

Philanthropy has an important role to play in influencing how people perceive our place in the world and understand the impact of human activity on the rest of the planet. I believe it's philanthropy's role to take risks, to invest early in innovative technologies, to lead where governments and industry aren't ready to go yet. We're fortunate at this time to be able to help those working on tools to better diagnose and treat the virus, and to invest in those working to improve information systems, so citizens and policy makers can make better decisions that can reduce impacts on families and institutions.

From all we know, this isn't likely to be the last pandemic the world will see. It's been said that a crisis comes before change, and we would hope that we can play a role in furthering the work to build systems that are resilient—in information, energy, agriculture and in all the ways we work, recreate, and use the precious resources of our planet.

[This article was originally published on June 8th, 2020 as part of a standalone magazine called GOOD10: The Pandemic Issue. Produced as a partnership among LeapsMag, The Aspen Institute, and GOOD, the magazine is available for free online.]

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.