Eight Big Medical and Science Trends to Watch in 2021

Promising developments underway include advancements in gene and cell therapy, better testing for COVID, and a renewed focus on climate change.

The world as we know it has forever changed. With a greater focus on science and technology than before, experts in the biotech and life sciences spaces are grappling with what comes next as SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes the COVID-19 illness, has spread and mutated across the world.

Even with vaccines being distributed, so much still remains unknown.

Jared Auclair, Technical Supervisor for the Northeastern University's Life Science Testing Center in Burlington, Massachusetts, guides a COVID testing lab that cranks out thousands of coronavirus test results per day. His lab is also focused on monitoring the quality of new cell and gene therapy products coming to the market.

Here are trends Auclair and other experts are watching in 2021.

Better Diagnostic Testing for COVID

Expect improvements in COVID diagnostic testing and the ability to test at home.

There are currently three types of coronavirus tests. The molecular test—also known as the RT-PCR test, detects the virus's genetic material, and is highly accurate, but it can take days to receive results. There are also antibody tests, done through a blood draw, designed to test whether you've had COVID in the past. Finally, there's the quick antigen test that isn't as accurate as the PCR test, but can identify if people are going to infect others.

Last month, Lucira Health secured the U.S. FDA Emergency Use Authorization for the first prescription molecular diagnostic test for COVID-19 that can be performed at home. On December 15th, the Ellume Covid-19 Home Test received authorization as the first over-the-counter COVID-19 diagnostic antigen test that can be done at home without a prescription. The test uses a nasal swab that is connected to a smartphone app and returns results in 15-20 minutes. Similarly, the BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card Home Test received authorization on Dec. 16 for its 15-minute antigen test that can be used within the first seven days of onset of COIVD-19 symptoms.

Home testing has the possibility to impact the pandemic pretty drastically, Auclair says, but there are other considerations: the type and timing of test that is administered, how expensive is the test (and if it is financially feasible for the general public) and the ability of a home test taker to accurately administer the test.

"The vaccine roll-out will not eliminate the need for testing until late 2021 or early 2022."

Ideally, everyone would frequently get tested, but that would mean the cost of a single home test—which is expected to be around $30 or more—would need to be much cheaper, more in the $5 range.

Auclair expects "innovations in the diagnostic space to explode" with the need for more accurate, inexpensive, quicker COVID tests. Auclair foresees innovations to be at first focused on COVID point-of-care testing, but he expects improvements within diagnostic testing for other types of viruses and diseases too.

"We still need more testing to get the pandemic under control, likely over the next 12 months," Auclair says. "The vaccine roll-out will not eliminate the need for testing until late 2021 or early 2022."

Rise of mRNA-based Vaccines and Therapies

A year ago, vaccines weren't being talked about like they are today.

"But clearly vaccines are the talk of the town," Auclair says. "The reason we got a vaccine so fast was there was so much money thrown at it."

A vaccine can take more than 10 years to fully develop, according to the World Economic Forum. Prior to the new COVID vaccines, which were remarkably developed and tested in under a year, the fastest vaccine ever made was for mumps -- and it took four years.

"Normally you have to produce a protein. This is typically done in eggs. It takes forever," says Catherine Dulac, a neuroscientist and developmental biologist at Harvard University who won the 2021 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences. "But an mRNA vaccine just enabled [us] to skip all sorts of steps [compared with burdensome conventional manufacturing] and go directly to a product that can be injected into people."

Non-traditional medicines based on genetic research are in their infancy. With mRNA-based vaccines hitting the market for the first time, look for more vaccines to be developed for whatever viruses we don't currently have vaccines for, like dengue virus and Ebola, Auclair says.

"There's a whole bunch of things that could be explored now that haven't been thought about in the past," Auclair says. "It could really be a game changer."

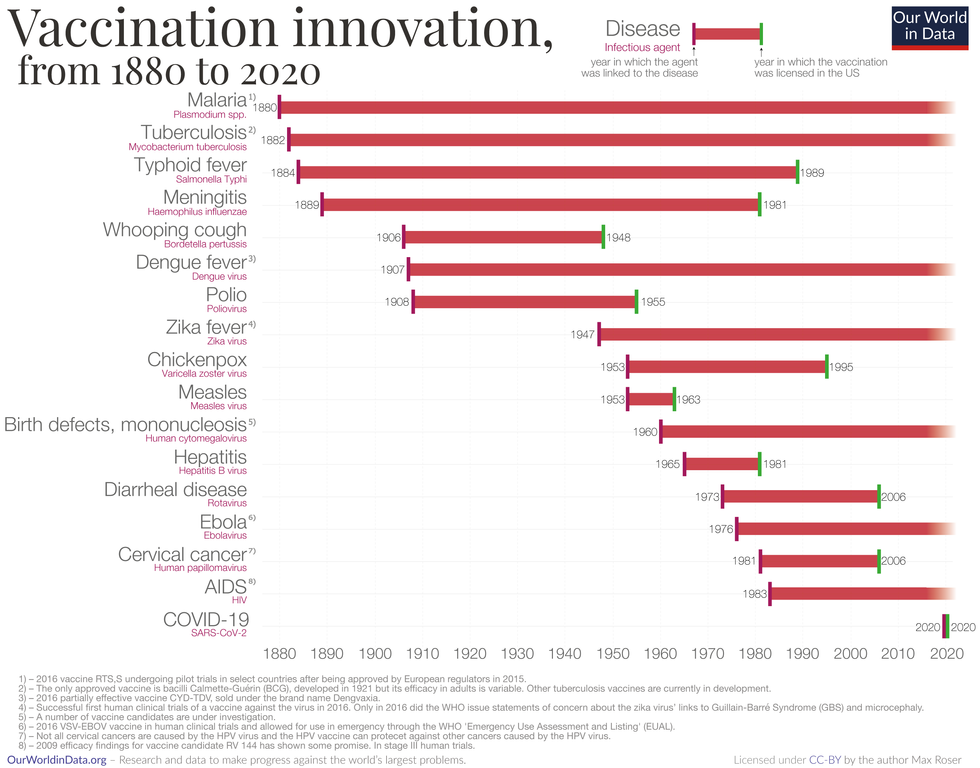

Vaccine Innovation over the last 140 years.

Max Roser/Our World in Data (Creative Commons license)

Advancements in Cell and Gene Therapies

CRISPR, a type of gene editing, is going to be huge in 2021, especially after the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna in October for pioneering the technology.

Right now, CRISPR isn't completely precise and can cause deletions or rearrangements of DNA.

"It's definitely not there yet, but over the next year it's going to get a lot closer and you're going to have a lot of momentum in this space," Auclair says. "CRISPR is one of the technologies I'm most excited about and 2021 is the year for it."

Gene therapies are typically used on rare genetic diseases. They work by replacing the faulty dysfunctional genes with corrected DNA codes.

"Cell and gene therapies are really where the field is going," Auclair says. "There is so much opportunity....For the first time in our life, in our existence as a species, we may actually be able to cure disease by using [techniques] like gene editing, where you cut in and out of pieces of DNA that caused a disease and put in healthy DNA," Auclair says.

For example, Spinal Muscular Atrophy is a rare genetic disorder that leads to muscle weakness, paralysis and death in children by age two. As of last year, afflicted children can take a gene therapy drug called Zolgensma that targets the missing or nonworking SMN1 gene with a new copy.

Another recent breakthrough uses gene editing for sickle cell disease. Victoria Gray, a mom from Mississippi who was exclusively followed by NPR, was the first person in the United States to be successfully treated for the genetic disorder with the help of CRISPR. She has continued to improve since her landmark treatment on July 2, 2019 and her once-debilitating pain has greatly eased.

"This is really a life-changer for me," she told NPR. "It's magnificent."

"You are going to see bigger leaps in gene therapies."

Look out also for improvements in cell therapies, but on a much lesser scale.

Cell therapies remove immune cells from a person or use cells from a donor. The cells are modified or cultured in lab, multiplied by the millions and then injected back into patients. These include stem cell therapies as well as CAR-T cell therapies, which are typically therapies of last resort and used in cancers like leukemia, Auclair says.

"You are going to see bigger leaps in gene therapies," Auclair says. "It's being heavily researched and we understand more about how to do gene therapies. Cell therapies will lie behind it a bit because they are so much more difficult to work with right now."

More Monoclonal Antibody Therapies

Look for more customized drugs to personalize medicine even more in the biotechnology space.

In 2019, the FDA anticipated receiving more than 200 Investigational New Drug (IND) applications in 2020. But with COVID, the number of INDs skyrocketed to 6,954 applications for the 2020 fiscal year, which ended September 30, 2020, according to the FDA's online tracker. Look for antibody therapies to play a bigger role.

Monoclonal antibodies are lab-grown proteins that mimic or enhance the immune system's response to fight off pathogens, like viruses, and they've been used to treat cancer. Now they are being used to treat patients with COVID-19.

President Donald Trump received a monoclonal antibody cocktail, called REGEN-COV2, which later received FDA emergency use authorization.

A newer type of monoclonal antibody therapy is Antibody-Drug Conjugates, also called ADCs. It's something we're going to be hearing a lot about in 2021, Auclair says.

"Antibody-Drug Conjugates is a monoclonal antibody with a chemical, we consider it a chemical warhead on it," Auclair says. "The monoclonal antibody binds to a specific antigen in your body or protein and delivers a chemical to that location and kills the infected cell."

Moving Beyond Male-Centric Lab Testing

Scientific testing for biology has, until recently, focused on testing males. Dulac, a Howard Hughes Medical Investigator and professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University, challenged that idea to find brain circuitry behind sex-specific behaviors.

"For the longest time, until now, all the model systems in biology, are male," Dulac says. "The idea is if you do testing on males, you don't need to do testing on females."

Clinical models are done in male animals, as well as fundamental research. Because biological research is always done on male models, Dulac says the outcomes and understanding in biology is geared towards understanding male biology.

"All the drugs currently on the market and diagnoses of diseases are biased towards the understanding of male biology," Dulac says. "The diagnostics of diseases is way weaker in women than men."

That means the treatment isn't necessarily as good for women as men, she says, including what is known and understood about pain medication.

"So pain medication doesn't work well in women," Dulac says. "It works way better in men. It's true for almost all diseases that I know. Why? because you have a science that is dominated by males."

Although some in the scientific community challenge that females are not interesting or too complicated with their hormonal variations, Dulac says that's simply not true.

"There's absolutely no reason to decide 50% of life forms are interesting and the other 50% are not interesting. What about looking at both?" says Dulac, who was awarded the $3 million Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences in September for connecting specific neural mechanisms to male and female parenting behaviors.

Disease Research on Single Cells

To better understand how diseases manifest in the body's cell and tissues, many researchers are looking at single-cell biology. Cells are the most fundamental building blocks of life. Much still needs to be learned.

"A remarkable development this year is the massive use of analysis of gene expression and chromosomal regulation at the single-cell level," Dulac says.

Much is focused on the Human Cell Atlas (HCA), a global initiative to map all cells in healthy humans and to better identify which genes associated with diseases are active in a person's body. Most estimates put the number of cells around 30 trillion.

Dulac points to work being conducted by the Cell Census Network (BICCN) Brain Initiative, an initiative by the National Institutes of Health to come up with an atlas of cell types in mouse, human and non-human primate brains, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative's funding of single-cell biology projects, including those focused on single-cell analysis of inflammation.

"Our body and our brain are made of a large number of cell types," Dulac says. "The ability to explore and identify differences in gene expression and regulation in massively multiplex ways by analyzing millions of cells is extraordinarily important."

Converting Plastics into Food

Yep, you heard it right, plastics may eventually be turned into food. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, better known as DARPA, is funding a project—formally titled "Production of Macronutrients from Thermally Oxo-Degraded Wastes"—and asking researchers how to do this.

"When I first heard about this challenge, I thought it was absolutely absurd," says Dr. Robert Brown, director of the Bioeconomy Institute at Iowa State University and the project's principal investigator, who is working with other research partners at the University of Delaware, Sandia National Laboratories, and the American Institute of Chemical Engineering (AIChE)/RAPID Institute.

But then Brown realized plastics will slowly start oxidizing—taking in oxygen—and microorganisms can then consume it. The oxidation process at room temperature is extremely slow, however, which makes plastics essentially not biodegradable, Brown says.

That changes when heat is applied at brick pizza oven-like temperatures around 900-degrees Fahrenheit. The high temperatures get compounds to oxidize rapidly. Plastics are synthetic polymers made from petroleum—large molecules formed by linking many molecules together in a chain. Heated, these polymers will melt and crack into smaller molecules, causing them to vaporize in a process called devolatilization. Air is then used to cause oxidation in plastics and produce oxygenated compounds—fatty acids and alcohols—that microorganisms will eat and grow into single-cell proteins that can be used as an ingredient or substitute in protein-rich foods.

"The caveat is the microorganisms must be food-safe, something that we can consume," Brown says. "Like supplemental or nutritional yeast, like we use to brew beer and to make bread or is used in Australia to make Vegemite."

What do the microorganisms look like? For any home beer brewers, it's the "gunky looking stuff you'd find at the bottom after the fermentation process," Brown says. "That's cellular biomass. Like corn grown in the field, yeast or other microorganisms like bacteria can be harvested as macro-nutrients."

Brown says DARPA's ReSource program has challenged all the project researchers to find ways for microorganisms to consume any plastics found in the waste stream coming out of a military expeditionary force, including all the packaging of food and supplies. Then the researchers aim to remake the plastic waste into products soldiers can use, including food. The project is in the first of three phases.

"We are talking about polyethylene, polypropylene, like PET plastics used in water bottles and converting that into macronutrients that are food," says Brown.

Renewed Focus on Climate Change

The Union of Concerned Scientists say carbon dioxide levels are higher today than any point in at least 800,000 years.

"Climate science is so important for all of humankind. It is critical because the quality of life of humans on the planet depends on it."

Look for technology to help locate large-scale emitters of carbon dioxide, including sensors on satellites and artificial intelligence to optimize energy usage, especially in data centers.

Other technologies focus on alleviating the root cause of climate change: emissions of heat-trapping gasses that mainly come from burning fossil fuels.

Direct air carbon capture, an emerging effort to capture carbon dioxide directly from ambient air, could play a role.

The technology is in the early stages of development and still highly uncertain, says Peter Frumhoff, director of science and policy at Union of Concerned Scientists. "There are a lot of questions about how to do that at sufficiently low costs...and how to scale it up so you can get carbon dioxide stored in the right way," he says, and it can be very energy intensive.

One of the oldest solutions is planting new forests, or restoring old ones, which can help convert carbon dioxide into oxygen through photosynthesis. Hence the Trillion Trees Initiative launched by the World Economic Forum. Trees are only part of the solution, because planting trees isn't enough on its own, Frumhoff says. That's especially true, since 2020 was the year that human-made, artificial stuff now outweighs all life on earth.

More research is also going into artificial photosynthesis for solar fuels. The U.S. Department of Energy awarded $100 million in 2020 to two entities that are conducting research. Look also for improvements in battery storage capacity to help electric vehicles, as well as back-up power sources for solar and wind power, Frumhoff says.

Another method to combat climate change is solar geoengineering, also called solar radiation management, which reflects sunlight back to space. The idea stems from a volcanic eruption in 1991 that released a tremendous amount of sulfate aerosol particles into the stratosphere, reflecting the sunlight away from Earth. The planet cooled by a half degree for nearly a year, Frumhoff says. However, he acknowledges, "there's a lot of things we don't know about the potential impacts and risks" involved in this controversial approach.

Whatever the approach, scientific solutions to climate change are attracting renewed attention. Under President Trump, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy didn't have an acting director for almost two years. Expect that to change when President-elect Joe Biden takes office.

"Climate science is so important for all of humankind," Dulac says. "It is critical because the quality of life of humans on the planet depends on it."

Some hospitals are pioneers in ditching plastic, turning green

In the U.S., hospitals generate an estimated 6,000 tons of waste per day. A few clinics are leading the way in transitioning to clean energy sources.

This is part 2 of a three part series on a new generation of doctors leading the charge to make the health care industry more sustainable - for the benefit of their patients and the planet. Read part 1 here and part 3 here.

After graduating from her studies as an engineer, Nora Stroetzel ticked off the top item on her bucket list and traveled the world for a year. She loved remote places like the Indonesian rain forest she reached only by hiking for several days on foot, mountain villages in the Himalayas, and diving at reefs that were only accessible by local fishing boats.

“But no matter how far from civilization I ventured, one thing was already there: plastic,” Stroetzel says. “Plastic that would stay there for centuries, on 12,000 foot peaks and on beaches several hundred miles from the nearest city.” She saw “wild orangutans that could be lured by rustling plastic and hermit crabs that used plastic lids as dwellings instead of shells.”

While traveling she started volunteering for beach cleanups and helped build a recycling station in Indonesia. But the pivotal moment for her came after she returned to her hometown Kiel in Germany. “At the dentist, they gave me a plastic cup to rinse my mouth. I used it for maybe ten seconds before it was tossed out,” Stroetzel says. “That made me really angry.”

She decided to research alternatives for plastic in the medical sector and learned that cups could be reused and easily disinfected. All dentists routinely disinfect their tools anyway and, Stroetzel reasoned, it wouldn’t be too hard to extend that practice to cups.

It's a good example for how often plastic is used unnecessarily in medical practice, she says. The health care sector is the fifth biggest source of pollution and trash in industrialized countries. In the U.S., hospitals generate an estimated 6,000 tons of waste per day, including an average of 400 grams of plastic per patient per day, and this sector produces 8.5 percent of greenhouse gas emissions nationwide.

“Sustainable alternatives exist,” Stroetzel says, “but you have to painstakingly look for them; they are often not offered by the big manufacturers, and all of this takes way too much time [that] medical staff simply does not have during their hectic days.”

When Stroetzel spoke with medical staff in Germany, she found they were often frustrated by all of this waste, especially as they took care to avoid single-use plastic at home. Doctors in other countries share this frustration. In a recent poll, nine out of ten doctors in Germany said they’re aware of the urgency to find sustainable solutions in the health industry but don’t know how to achieve this goal.

After a year of researching more sustainable alternatives, Stroetzel founded a social enterprise startup called POP, short for Practice Without Plastic, together with IT expert Nicolai Niethe, to offer well-researched solutions. “Sustainable alternatives exist,” she says, “but you have to painstakingly look for them; they are often not offered by the big manufacturers, and all of this takes way too much time [that] medical staff simply does not have during their hectic days.”

In addition to reusable dentist cups, other good options for the heath care sector include washable N95 face masks and gloves made from nitrile, which waste less water and energy in their production. But Stroetzel admits that truly making a medical facility more sustainable is a complex task. “This includes negotiating with manufacturers who often package medical materials in double and triple layers of extra plastic.”

While initiatives such as Stroetzel’s provide much needed information, other experts reason that a wholesale rethinking of healthcare is needed. Voluntary action won’t be enough, and government should set the right example. Kari Nadeau, a Stanford physician who has spent 30 years researching the effects of environmental pollution on the immune system, and Kenneth Kizer, the former undersecretary for health in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, wrote in JAMA last year that the medical industry and federal agencies that provide health care should be required to measure and make public their carbon footprints. “Government health systems do not disclose these data (and very rarely do private health care organizations), unlike more than 90% of the Standard & Poor’s top 500 companies and many nongovernment entities," they explained. "This could constitute a substantial step toward better equipping health professionals to confront climate change and other planetary health problems.”

Compared to the U.K., the U.S. healthcare industry lags behind in terms of measuring and managing its carbon footprint, and hospitals are the second highest energy user of any sector in the U.S.

Kizer and Nadeau look to the U.K. National Health Service (NHS), which created a Sustainable Development Unit in 2008 and began that year to conduct assessments of the NHS’s carbon footprint. The NHS also identified its biggest culprits: Of the 2019 footprint, with emissions totaling 25 megatons of carbon dioxide equivalent, 62 percent came from the supply chain, 24 percent from the direct delivery of care, 10 percent from staff commute and patient and visitor travel, and 4 percent from private health and care services commissioned by the NHS. From 1990 to 2019, the NHS has reduced its emission of carbon dioxide equivalents by 26 percent, mostly due to the switch to renewable energy for heat and power. Meanwhile, the NHS has encouraged health clinics in the U.K. to install wind generators or photovoltaics that convert light to electricity -- relatively quick ways to decarbonize buildings in the health sector.

Compared to the U.K., the U.S. healthcare industry lags behind in terms of measuring and managing its carbon footprint, and hospitals are the second highest energy user of any sector in the U.S. “We are already seeing patients with symptoms from climate change, such as worsened respiratory symptoms from increased wildfires and poor air quality in California,” write Thomas B. Newman, a pediatrist at the University of California, San Francisco, and UCSF clinical research coordinator Daisy Valdivieso. “Because of the enormous health threat posed by climate change, health professionals should mobilize support for climate mitigation and adaptation efforts.” They believe “the most direct place to start is to approach the low-lying fruit: reducing healthcare waste and overuse.”

In addition to resulting in waste, the plastic in hospitals ultimately harms patients, who may be even more vulnerable to the effects due to their health conditions. Microplastics have been detected in most humans, and on average, a human ingests five grams of microplastic per week. Newman and Valdivieso refer to the American Board of Internal Medicine's Choosing Wisely program as one of many initiatives that identify and publicize options for “safely doing less” as a strategy to reduce unnecessary healthcare practices, and in turn, reduce cost, resource use, and ultimately reduce medical harm.

A few U.S. clinics are pioneers in transitioning to clean energy sources. In Wisconsin, the nonprofit Gundersen Health network became the first hospital to cut its reliance on petroleum by switching to locally produced green energy in 2015, and it saved $1.2 million per year in the process. Kaiser Permanente eliminated its 800,000 ton carbon footprint through energy efficiency and purchasing carbon offsets, reaching a balance between carbon emissions and removing carbon from the atmosphere in 2020, the first U.S. health system to do so.

Cleveland Clinic has pledged to join Kaiser in becoming carbon neutral by 2027. Realizing that 80 percent of its 2008 carbon emissions came from electricity consumption, the Clinic started switching to renewable energy and installing solar panels, and it has invested in researching recyclable products and packaging. The Clinic’s sustainability report outlines several strategies for producing less waste, such as reusing cases for sterilizing instruments, cutting back on materials that can’t be recycled, and putting pressure on vendors to reduce product packaging.

The Charité Berlin, Europe’s biggest university hospital, has also announced its goal to become carbon neutral. Its sustainability managers have begun to identify the biggest carbon culprits in its operations. “We’ve already reduced CO2 emissions by 21 percent since 2016,” says Simon Batt-Nauerz, the director of infrastructure and sustainability.

The hospital still emits 100,000 tons of CO2 every year, as much as a city with 10,000 residents, but it’s making progress through ride share and bicycle programs for its staff of 20,000 employees, who can get their bikes repaired for free in one of the Charité-operated bike workshops. Another program targets doctors’ and nurses’ scrubs, which cause more than 200 tons of CO2 during manufacturing and cleaning. The staff is currently testing lighter, more sustainable scrubs made from recycled cellulose that is grown regionally and requires 80 percent less land use and 30 percent less water.

The Charité hospital in Berlin still emits 100,000 tons of CO2 every year, but it’s making progress through ride share and bicycle programs for its staff of 20,000 employees.

Wiebke Peitz | Specific to Charité

Anesthesiologist Susanne Koch spearheads sustainability efforts in anesthesiology at the Charité. She says that up to a third of hospital waste comes from surgery rooms. To reduce medical waste, she recommends what she calls the 5 Rs: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Rethink, Research. “In medicine, people don’t question the use of plastic because of safety concerns,” she says. “Nobody wants to be sued because something is reused. However, it is possible to reduce plastic and other materials safely.”

For instance, she says, typical surgery kits are single-use and contain more supplies than are actually needed, and the entire kit is routinely thrown out after the surgery. “Up to 20 percent of materials in a surgery room aren’t used but will be discarded,” Koch says. One solution could be smaller kits, she explains, and another would be to recycle the plastic. Another example is breathing tubes. “When they became scarce during the pandemic, studies showed that they can be used seven days instead of 24 hours without increased bacteria load when we change the filters regularly,” Koch says, and wonders, “What else can we reuse?”

In the Netherlands, TU Delft researchers Tim Horeman and Bart van Straten designed a method to melt down the blue polypropylene wrapping paper that keeps medical instruments sterile, so that the material can be turned it into new medical devices. Currently, more than a million kilos of the blue paper are used in Dutch hospitals every year. A growing number of Dutch hospitals are adopting this approach.

Another common practice that’s ripe for improvement is the use of a certain plastic, called PVC, in hospital equipment such as blood bags, tubes and masks. Because of its toxic components, PVC is almost never recycled in the U.S., but University of Michigan researchers Danielle Fagnani and Anne McNeil have discovered a chemical process that can break it down into material that could be incorporated back into production. This could be a step toward a circular economy “that accounts for resource inputs and emissions throughout a product’s life cycle, including extraction of raw materials, manufacturing, transport, use and reuse, and disposal,” as medical experts have proposed. “It’s a failure of humanity to have created these amazing materials which have improved our lives in many ways, but at the same time to be so shortsighted that we didn’t think about what to do with the waste,” McNeil said in a press release.

Susanne Koch puts it more succinctly: “What’s the point if we save patients while killing the planet?”

The Friday Five: A surprising health benefit for people who have kids

In this week's Friday Five, your kids may be stressing you out, but research suggests they're actually protecting a key aspect of your health. Plus, a new device unlocks the heart's secrets, super-ager gene transplants and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- Kids stressing you out? They could be protecting your health.

- A new device unlocks the heart's secrets

- Super-ager gene transplants

- Surgeons could 3D print your organs before operations

- A skull cap looks into the brain like an fMRI