Elizabeth Holmes Through the Director’s Lens

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Elizabeth Holmes.

"The Inventor," a chronicle of Theranos's storied downfall, premiered recently on HBO. Leapsmag reached out to director Alex Gibney, whom The New York Times has called "one of America's most successful and prolific documentary filmmakers," for his perspective on Elizabeth Holmes and the world she inhabited.

Do you think Elizabeth Holmes was a charismatic sociopath from the start — or is she someone who had good intentions, over-promised, and began the lies to keep her business afloat, a "fake it till you make it" entrepreneur like Thomas Edison?

I'm not qualified to say if EH was or is a sociopath. I don't think she started Theranos as a scam whose only purpose was to make money. If she had done so, she surely would have taken more money for herself along the way. I do think that she had good intentions and that she, as you say, "began the lies to keep her business afloat." ([Reporter John] Carreyrou's book points out that those lies began early.) I think that the Edison comparison is instructive for a lot of reasons.

First, Edison was the original "fake-it-till-you-make-it" entrepreneur. That puts this kind of behavior in the mainstream of American business. By saying that, I am NOT endorsing the ethic, just the opposite. As one Enron executive mused about the mendacity there, "Was it fraud or was it bad marketing?" That gives you a sense of how baked-in the "fake it" sensibility is.

"Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals."

I think EH shares one other thing with Edison, which is a huge ego coupled with a talent for storytelling as long as she is the heroic, larger-than-life main character. It's interesting that EH calls her initial device "Edison." Edison was the world's most famous "inventor," both because of the devices that came out of his shop and and for his ability for "self-invention." As Randall Stross notes in "The Wizard of Menlo Park," he was the first celebrity businessman. In addition to her "good intentions," EH was certainly motivated by fame and glory and many of her lies were in service to those goals.

Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals. That doesn't excuse the lies. But those noble goals may have allowed EH to excuse them for herself or, more perniciously, to make believe that they weren't lies at all. This is where we get into scary psychological territory.

But rather than thinking of it as freakish, I think it's more productive to think of it as an exaggeration of the way we all lie to others and to ourselves. That's the point of including the Dan Ariely experiment with the dice. In that experiment, most of the subjects cheated more when they thought they were doing it for a good cause. Even more disturbing, that "good cause" allowed them to lie much more effectively because they had come to believe they weren't doing anything wrong. As it turns out, economics isn't a rational practice; it's the practice of rationalizing.

Where EH and Edison differ is that Edison had a firm grip on reality. He knew he could find a way to make the incandescent lightbulb work. There is no evidence that EH was close to making her "Edison" work. But rather than face reality (and possibly adjust her goals) she pretended that her dream was real. That kind of "over-promising" or "bold vision" is one thing when you are making a prototype in the lab. It's a far more serious matter when you are using a deeply flawed system on real patients. EH can tell herself that she had to do that (Walgreens was ready to walk away if she hadn't "gone live") or else Theranos would have run out of money.

But look at the calculation she made: she thought it was worth putting lives at risk in order to make her dream come true. Now we're getting into the realm of the sociopath. But my experience leads me to believe that -- as in the case of the Milgram experiment -- most people don't do terrible things right away, they come to crimes gradually as they become more comfortable with bigger and bigger rationalizations. At Theranos, the more valuable the company became, the bigger grew the lies.

The two whistleblowers come across as courageous heroes, going up against the powerful and intimidating company. The contrast between their youth and lack of power and the old elite backers of Theronos is staggering, and yet justice triumphed. Were the whistleblowers hesitant or afraid to appear in the film, or were they eager to share their stories?

By the time I got to them, they were willing and eager to tell their stories, once I convinced them that I would honor their testimony. In the case of Erika and Tyler, they were nudged to participate by John Carreyrou, in whom they had enormous trust.

"It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box."

Why do you think so many elite veterans of politics and venture capitalism succumbed to Holmes' narrative in the first place, without checking into the details of its technology or financials?

The reasons are all in the film. First, Channing Robertson and many of the old men on her board were clearly charmed by her and maybe attracted to her. They may have rationalized their attraction by convincing themselves it was for a good cause! Second, as Dan Ariely tells us, we all respond to stories -- more than graphs and data -- because they stir us emotionally. EH was a great storyteller. Third, the story of her as a female inventor and entrepreneur in male-dominated Silicon Valley is a tale that they wanted to invest in.

There may have been other factors. EH was very clever about the way she put together an ensemble of credibility. How could Channing Robertson, George Shultz, Henry Kissinger and Jim Mattis all be wrong? And when Walgreens put the Wellness Centers in stores, investors like Rupert Murdoch assumed that Walgreens must have done its due diligence. But they hadn't!

It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box. But that blind faith, as it turns out, is more a part of capitalism than we have been taught.

Do you think that Roger Parloff deserves any blame for the glowing Fortune story on Theranos, since he appears in the film to blame himself? Or was he just one more victim of Theranos's fraud?

He put her on the cover of Fortune so he deserves some blame for the fraud. He still blames himself. That willingness to hold himself to account shows how seriously he takes the job of a journalist. Unlike Elizabeth, Roger has the honesty and moral integrity to admit that he made a mistake. He owned up to it and published a mea culpa. That said, Roger was also a victim because Elizabeth lied to him.

Do you think investors in Silicon Valley, with their FOMO attitudes and deep pockets, are vulnerable to making the same mistake again with a shiny new startup, or has this saga been a sober reminder to do their due diligence first?

Many of the mistakes made with Theranos were the same mistakes made with Enron. We must learn to recognize that we are, by nature, trusting souls. Knowing that should lead us to a guiding slogan: "trust but verify."

The irony of Holmes dancing to "I Can't Touch This" is almost too perfect. How did you find that footage?

It was leaked to us.

"Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of 'The Apprentice.'"

Holmes is facing up to 20 years in prison for federal fraud charges, but Vanity Fair recently reported that she is seeking redemption, taking meetings with filmmakers for a possible documentary to share her "real" story. What do you think will become of Holmes in the long run?

It's usually a mistake to handicap a trial. My guess is that she will be convicted and do some prison time. But maybe she can convince jurors -- the way she convinced journalists, her board, and her investors -- that, on account of her noble intentions, she deserves to be found not guilty. "Somewhere, over the rainbow…"

After the trial, and possibly prison, I'm sure that EH will use her supporters (like Tim Draper) to find a way to use the virtual currency of her celebrity to rebrand herself and launch something new. Fitzgerald famously said that "there are no second acts in American lives." That may be the stupidest thing he ever said.

Donald Trump failed at virtually every business he ever embarked on. But he became a celebrity for being a fake businessman and used that celebrity -- and phony expertise -- to become president of the United States. Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of "The Apprentice." And then?

"You Can't Touch This!"

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A healthy middle-aged couple enjoying a hike. (Shutterstock)

[Editor's Note: This video is the fourth of a five-part series titled "The Future Is Now: The Revolutionary Power of Stem Cell Research." Produced in partnership with the Regenerative Medicine Foundation, and filmed at the annual 2019 World Stem Cell Summit, this series illustrates how stem cell research will profoundly impact human life.]

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

He Almost Died from a Deadly Superbug. A Virus Saved Him.

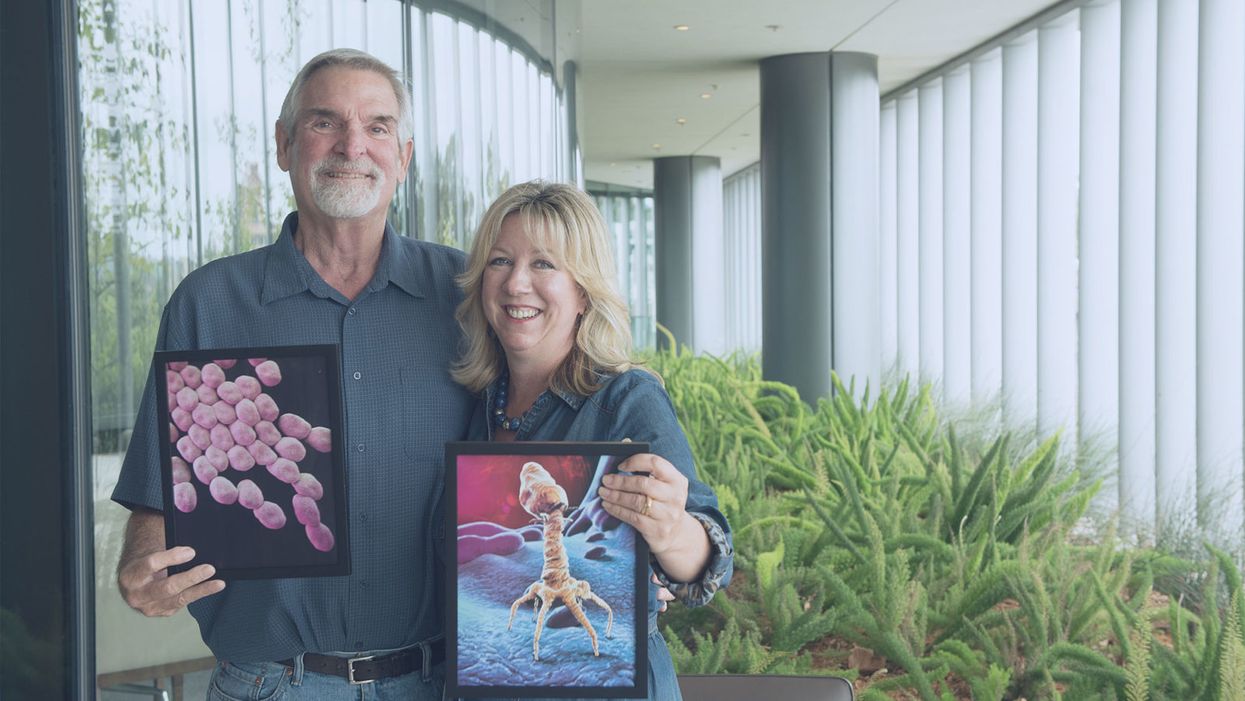

Tom Patterson holding an image of Acinetobacter baumannii and Steffanie Strathdee holding an image of a bacteriophage.

An attacking rogue hippo, giant jumping spiders, even a coup in Timbuktu couldn't knock out Tom Patterson, but now he was losing the fight against a microscopic bacteria.

Death seemed inevitable, perhaps hours away, despite heroic efforts to keep him alive.

It was the deadly drug-resistant superbug Acinetobacter baumannii. The infection struck during a holiday trip with his wife to the pyramids in Egypt and had sent his body into toxic shock. His health was deteriorating so rapidly that his insurance company paid to medevac him first to Germany, then home to San Diego.

Weeks passed as he lay in a coma, shedding more than a hundred pounds. Several major organs were on the precipice of collapse, and death seemed inevitable, perhaps hours away despite heroic efforts by a major research university hospital to keep Tom alive.

Tom Patterson in a deep coma on March 14, 2016, the day before phage therapy was initiated.

(Courtesy Steffanie Strathdee)

Then doctors tried something boldly experimental -- injecting him with a cocktail of bacteriophages, tiny viruses that might infect and kill the bacteria ravaging his body.

It worked. Days later Tom's eyes fluttered open for a few brief seconds, signaling that the corner had been turned. Recovery would take more weeks in the hospital and about a year of rehabilitation before life began to resemble anything near normal.

In her new book The Perfect Predator, Tom's wife, Steffanie Strathdee, recounts the personal and scientific ordeal from twin perspectives as not only his spouse but also as a research epidemiologist who has traveled the world to track down diseases.

Part of the reason why Steff wrote the book is that both she and Tom suffered severe PTSD after his illness. She says they also felt it was "part of our mission, to ensure that phage therapy wasn't going to be forgotten for another hundred years."

Tom Patterson and Steffanie Strathdee taking a first breath of fresh air during recovery outside the UCSD hospital.

(Courtesy Steffanie Strathdee)

From Prehistoric Arms Race to Medical Marvel

Bacteriophages, or phages for short, evolved as part of the natural ecosystem. They are viruses that infect bacteria, hijacking their host's cellular mechanisms to reproduce themselves, and in the process destroying the bacteria. The entire cycle plays out in about 20-60 minutes, explains Ben Chan, a phage research scientist at Yale University.

They were first used to treat bacterial infections a century ago. But the development of antibiotics soon eclipsed their use as medicine and a combination of scientific, economic, and political factors relegated them to a dusty corner of science. The emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria has highlighted the limitations of antibiotics and prompted a search for new approaches, including a revived interest in phages.

Most phages are very picky, seeking out not just a specific type of bacteria, but often a specific strain within a family of bacteria. They also prefer to infect healthy replicating bacteria, not those that are at rest. That's what makes them so intriguing to tap as potential therapy.

Tom's case was one of the first times that phages were successfully infused into the bloodstream of a human.

Phages and bacteria evolved measures and countermeasures to each other in an "arms race" that began near the dawn of life on the planet. It is not that one consciously tries to thwart the other, says Chan, it's that countless variations of each exists in the world and when a phage gains the upper hand and kills off susceptible bacteria, it opens up a space in the ecosystem for similar bacteria that are not vulnerable to the phage to increase in numbers. Then a new phage variant comes along and the cycle repeats.

Robert "Chip" Schooley is head of infectious diseases at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine and a leading expert on treating HIV. He had no background with phages but when Steff, a friend and colleague, approached him in desperation about using them with Tom, he sprang into action to learn all he could, and to create a network of experts who might provide phages capable of killing Acinetobacter.

"There is very little evidence that phage[s] are dangerous," Chip concluded after first reviewing the literature and now after a few years of experience using them. He compares broad-spectrum antibiotics to using a bazooka, where every time you use them, less and less of the "good" bacteria in the body are left. "With a phage cocktail what you're really doing is more of a laser."

Collaborating labs were able to identify two sets of phage cocktails that were sensitive to Tom's particular bacterial infection. And the FDA acted with lightning speed to authorize the experimental treatment.

A bag of a four-phage "cocktail" before being infused into Tom Patterson.

(Courtesy Steffanie Strathdee)

Tom's case was scientifically important because it was one of the first times that phages were successfully infused into the bloodstream of a human. Most prior use of phages involved swallowing them or placing them directly on the area of infection.

The success has since sparked a renewed interest in phages and a reexamination of their possible role in medicine.

Over the two years since Tom awoke from his coma, several other people around the world have been successfully treated with phages as part of their regimen, after antibiotics have failed.

The Future of Phage Therapy

The experience treating Tom prompted UCSD to create the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH), with Chip and Steff as co-directors. Previous labs have engaged in basic research on phages, but this is the first clinical center in North America to focus on translating that knowledge into treating patients.

In January, IPATH announced the first phase 2 clinical trial approved by the FDA that will use phages intravenously. The viruses are being developed by AmpliPhi Biosciences, a San Diego-based company that supplied one of the phages used to treat Tom. The new study takes on drug resistant Staph aureus bacteria. Experimental phage therapy treatment using the company's product candidates was recently completed in 21 patients at seven hospitals who had been suffering from serious infections that did not respond to antibiotics. The reported success rate was 84 percent.

The new era of phage research is applying cutting-edge biologic and informatics tools to better understand and reshape the viruses to better attack bacteria, evade resistance, and perhaps broaden their reach a bit within a bacterial family.

Genetic engineering tools are being used to enhance the phages' ability to infect targeted bacteria.

"As we learn more and more about which biological activities are critical and in which clinical settings, there are going to be ways to optimize these activities," says Chip. Sometimes phages may be used alone, other times in combination with antibiotics.

Genetic engineering using tools are being used to enhance the phages' ability to infect targeted bacteria and better counter evolving forms of bacterial resistance in the ongoing "arms race" between the two. It isn't just theory. A patient recently was successfully treated with a genetically modified phage as part of the regimen, and the paper is in press.

In reality, given the trillions of phages in the world and the endless encounters they have had with bacteria over the millennia, it is likely that the exact phages needed to kill off certain bacteria already exist in nature. Using CRISPR to modify a phage is simply a quick way to identify the right phage useful for a given patient and produce it in the necessary quantities, rather than go search for the proverbial phage needle in a sewage haystack, says Chan.

One non-medical reason why using modified phages could be significant is that it creates an intellectual property stake, something that is patentable with a period of exclusive use. Major pharmaceutical companies and venture capitalists have been hesitant to invest in organisms found in nature; but a patentable modification may be enough to draw their interest to phage development and provide the funding for large-scale clinical trials necessary for FDA approval and broader use.

"There are 10 million trillion trillion phages on the planet, 10 to the power of 31. And the fact is that this ongoing evolutionary arms race between bacteria and phage, they've been at it for a millennia," says Steff. "We just need to exploit it."