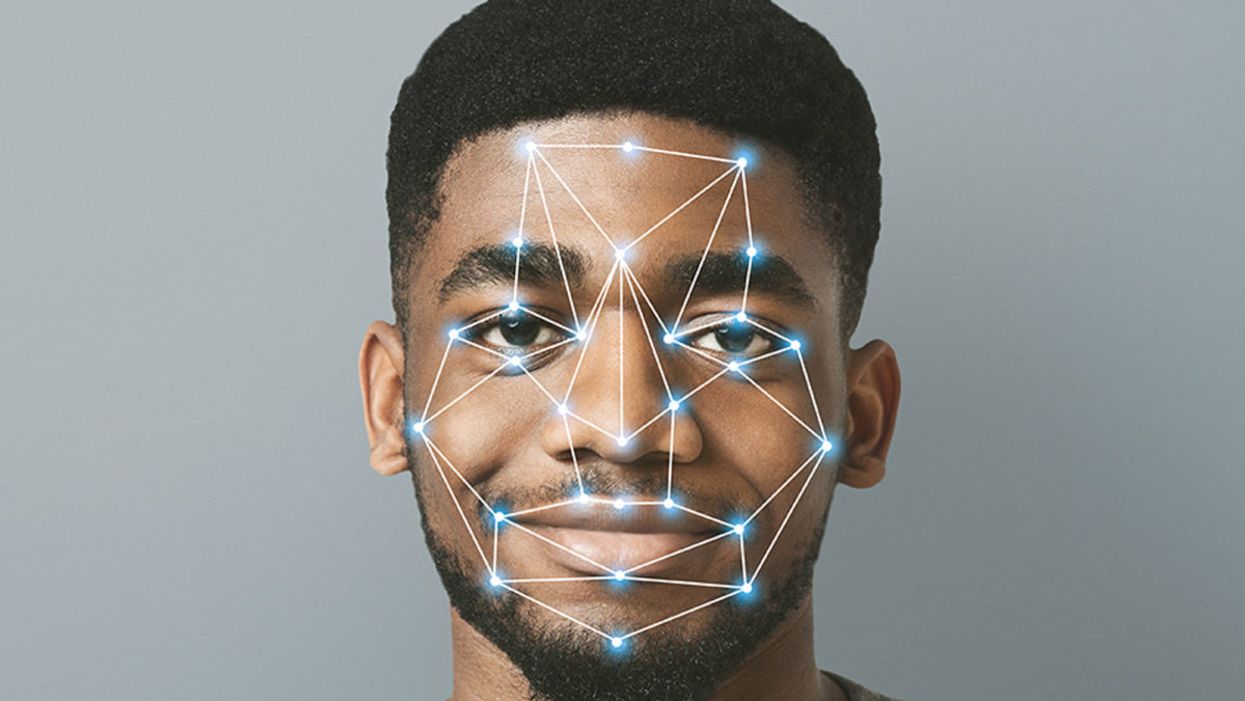

Facial Recognition Can Reduce Racial Profiling and False Arrests

The use of face recognition technology is expanding exponentially right now.

[Editor's Note: This essay is in response to our current Big Question, which we posed to experts with different perspectives: "Do you think the use of facial recognition technology by the police or government should be banned? If so, why? If not, what limits, if any, should be placed on its use?"]

Opposing facial recognition technology has become an article of faith for civil libertarians. Many who supported the bans in cities like San Francisco and Oakland have declared the technology to be inherently racist and abusive.

The greatest danger would be to categorically oppose this technology and pretend that it will simply go away.

I have spent my career as a criminal defense attorney and a civil libertarian -- and I do not fear it. Indeed, I see it as positive so long as it is appropriately regulated and controlled.

We are living in the beginning of a biometric age, where technology uses our physical or biological characteristics for a variety of products and services. It holds great promises as well as great risks. The greatest danger, however, would be to categorically oppose this technology and pretend that it will simply go away.

This is an age driven as much by consumer as it is government demand. Living in denial may be emotionally appealing, but it will only hasten the creation of post-privacy world. If we do not address this emerging technology, movements in public will increasingly result in instant recognition and even tracking. It is the type of fish-bowl society that strips away any expectation of privacy in our interactions and associations.

The biometrics field is expanding exponentially, largely due to the popularity of consumer products using facial recognition technology (FRT) -- from the iPhone program to shopping ones that recognize customers.

But the privacy community is losing this battle because it is using the privacy rationales and doctrines forged in the earlier electronic surveillance periods. Just as generals are often accused of planning to fight the last war, civil libertarians can sometimes cling to past models despite their decreasing relevance in the current world.

I see FRT as having positive implications that are worth pursuing. When properly used, biometrics can actually enhance privacy interests and even reduce racial profiling by reducing false arrests and the warrantless "patdowns" allowed by the Supreme Court. Bans not only deny police a technology widely used by businesses, but return police to the highly flawed default of "eye balling" suspects -- a system with a considerably higher error rate than top FRT programs.

Officers are often wrong and stop a great number of suspects in the hopes of finding a wanted felon.

A study in Australia showed that passport officers who had taken photographs of subjects in ideal conditions nonetheless experienced high error rates when identifying them shortly afterward, including 14 percent false acceptance rates. Currently, officers stop suspects based on their memory from seeing a photograph days or weeks earlier. They are often wrong and stop a great number of suspects in the hopes of finding a wanted felon. The best FRT programs achieve an astonishing accuracy rate, though real-world implementation has challenges that must be addressed.

One legitimate concern raised in early studies showed higher error rates in recognitions for certain groups, particularly African American women. An MIT study finding that error rate prompted major improvements in the algorithms as well as training changes to greatly reduce the frequency of errors. The issue remains a concern, but there is nothing inherently racist in algorithms. These are a set of computer instructions that isolate and process with the parameters and conditions set by creators.

To be sure, there is room for improvement in some algorithms. Tests performed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reportedly showed only an 80 percent accuracy rate in comparing mug shots to pictures of members of Congress when using Amazon's "Rekognition" system. It recently showed the same 80 percent rate in doing the same comparison to members of the California legislators.

However, different algorithms are available with differing levels of performance. Moreover, these products can be set with a lower discrimination level. The fact is that the top algorithms tested by the National Institute of Standards and Technology showed that their accuracy rate is greater than 99 percent.

The greatest threat of biometric technologies is to democratic values.

Assuming a top-performing algorithm is used, the result could be highly beneficial for civil liberties as opposed to the alternative of "eye balling" suspects. Consider the Boston Bombing where police declared a "containment zone" and forced families into the street with their hands in the air.

The suspect, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, moved around Boston and was ultimately found outside the "containment zone" once authorities abandoned near martial law. He was caught on some surveillance systems but not identified. FRT can help law enforcement avoid time-consuming area searches and the questionable practice of forcing people out of their homes to physically examine them.

If we are to avoid a post-privacy world, we will have to redefine what we are trying to protect and reconceive how we hope to protect it. In my view, the greatest threat of biometric technologies is to democratic values. Authoritarian nations like China have made huge investments into FRT precisely because they know that the threat of recognition in public deters citizens from associating or interacting with protesters or dissidents. Recognition changes conduct. That chilling effect is what we have the worry about the most.

Conventional privacy doctrines do not offer much protection. The very concept of "public privacy" is treated as something of an oxymoron by courts. Public acts and associations are treated as lacking any reasonable expectation of privacy. In the same vein, the right to anonymity is not a strong avenue for protection. We are not living in an anonymous world anymore.

Consumers want products like FaceFind, which link their images with others across social media. They like "frictionless" transactions and authentications using faceprints. Despite the hyperbole in places like San Francisco, civil libertarians will not succeed in getting that cat to walk backwards.

The basis for biometric privacy protection should not be focused on anonymity, but rather obscurity. You will be increasingly subject to transparency-forcing technology, but we can legislatively mandate ways of obscuring that information. That is the objective of the Biometric Privacy Act that I have proposed in recent research. However, no such comprehensive legislation has passed through Congress.

The ability to spot fraudulent entries at airports or recognizing a felon in flight has obvious benefits for all citizens.

We also need to recognize that FRT has many beneficial uses. Biometric guns can reduce accidents and criminals' conduct. New authentications using FRT and other biometric programs could reduce identity theft.

And, yes, FRT could help protect against unnecessary police stops or false arrests. Finally, and not insignificantly, this technology could stop serious crimes, from terrorist attacks to the capturing of dangerous felons. The ability to spot fraudulent entries at airports or recognizing a felon in flight has obvious benefits for all citizens.

We can live and thrive in a biometric era. However, we will need to bring together civil libertarians with business and government experts if we are going to control this technology rather than have it control us.

[Editor's Note: Read the opposite perspective here.]

Fast for Longevity, with Less Hunger, with Dr. Valter Longo

Valter Longo, a biogerontologist at USC, and centenarian Rocco Longo (no relation) appear together in Italy in 2021. The elder Longo is from a part of Italy where people have fasted regularly and are enjoying long lifespans.

You’ve probably heard about intermittent fasting, where you don’t eat for about 16 hours each day and limit the window where you’re taking in food to the remaining eight hours.

But there’s another type of fasting, called a fasting-mimicking diet, with studies pointing to important benefits. For today’s podcast episode, I chatted with Dr. Valter Longo, a biogerontologist at the University of Southern California, about all kinds of fasting, and particularly the fasting-mimicking diet, which minimizes hunger as much as possible. Going without food for a period of time is an example of good stress: challenges that work at the cellular level to boost health and longevity.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

If you’ve ever spent more than a few minutes looking into fasting, you’ve almost certainly come upon Dr. Longo's name. He is the author of the bestselling book, The Longevity Diet, and the best known researcher of fasting-mimicking diets.

With intermittent fasting, your body might begin to switch up its fuel type. It's usually running on carbs you get from food, which gets turned into glucose, but without food, your liver starts making something called ketones, which are molecules that may benefit the body in a number of ways.

With the fasting-mimicking diet, you go for several days eating only types of food that, in a way, keep themselves secret from your body. So at the level of your cells, the body still thinks that it’s fasting. This is the best of both worlds – you’re not completely starving because you do take in some food, and you’re getting the boosts to health that come with letting a fast run longer than intermittent fasting. In this episode, Dr. Longo talks about the growing number of studies showing why this could be very advantageous for health, as long as you undertake the diet no more than a few times per year.

Dr. Longo is the director of the Longevity Institute at USC’s Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, and the director of the Longevity and Cancer program at the IFOM Institute of Molecular Oncology in Milan. In addition, he's the founder and president of the Create Cures Foundation in L.A., which focuses on nutrition for the prevention and treatment of major chronic illnesses. In 2016, he received the Glenn Award for Research on Aging for the discovery of genes and dietary interventions that regulate aging and prevent diseases. Dr. Longo received his PhD in biochemistry from UCLA and completed his postdoc in the neurobiology of aging and Alzheimer’s at USC.

Show links:

Create Cures Foundation, founded by Dr. Longo: www.createcures.org

Dr. Longo's Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profvalterlongo/

Dr. Longo's Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/prof_valterlongo/

Dr. Longo's book: The Longevity Diet

The USC Longevity Institute: https://gero.usc.edu/longevity-institute/

Dr. Longo's research on nutrition, longevity and disease: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35487190/

Dr. Longo's research on fasting mimicking diet and cancer: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34707136/

Full list of Dr. Longo's studies: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Longo%2C+Valter%5BAuthor%5D&sort=date

Research on MCT oil and Alzheimer's: https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/f...

Keto Mojo device for measuring ketones

Silkworms with spider DNA spin silk stronger than Kevlar

Silkworm silk is fragile, which limits its uses, but a few extra genes can help.

Story by Freethink

The study and copying of nature’s models, systems, or elements to address complex human challenges is known as “biomimetics.” Five hundred years ago, an elderly Italian polymath spent months looking at the soaring flight of birds. The result was Leonardo da Vinci’s biomimetic Codex on the Flight of Birds, one of the foundational texts in the science of aerodynamics. It’s the science that elevated the Wright Brothers and has yet to peak.

Today, biomimetics is everywhere. Shark-inspired swimming trunks, gecko-inspired adhesives, and lotus-inspired water-repellents are all taken from observing the natural world. After millions of years of evolution, nature has quite a few tricks up its sleeve. They are tricks we can learn from. And now, thanks to some spider DNA and clever genetic engineering, we have another one to add to the list.

The elusive spider silk

We’ve known for a long time that spider silk is remarkable, in ways that synthetic fibers can’t emulate. Nylon is incredibly strong (it can support a lot of force), and Kevlar is incredibly tough (it can absorb a lot of force). But neither is both strong and tough. In all artificial polymeric fibers, strength and toughness are mutually exclusive, and so we pick the material best for the job and make do.

Spider silk, a natural polymeric fiber, breaks this rule. It is somehow both strong and tough. No surprise, then, that spider silk is a source of much study.The problem, though, is that spiders are incredibly hard to cultivate — let alone farm. If you put them together, they will attack and kill each other until only one or a few survive. If you put 100 spiders in an enclosed space, they will go about an aggressive, arachnocidal Hunger Games. You need to give each its own space and boundaries, and a spider hotel is hard and costly. Silkworms, on the other hand, are peaceful and productive. They’ll hang around all day to make the silk that has been used in textiles for centuries. But silkworm silk is fragile. It has very limited use.

The elusive – and lucrative – trick, then, would be to genetically engineer a silkworm to produce spider-quality silk. So far, efforts have been fruitless. That is, until now.

We can have silkworms creating silk six times as tough as Kevlar and ten times as strong as nylon.

Spider-silkworms

Junpeng Mi and his colleagues working at Donghua University, China, used CRISPR gene-editing technology to recode the silk-creating properties of a silkworm. First, they took genes from Araneus ventricosus, an East Asian orb-weaving spider known for its strong silk. Then they placed these complex genes – genes that involve more than 100 amino acids – into silkworm egg cells. (This description fails to capture how time-consuming, technical, and laborious this was; it’s a procedure that requires hundreds of thousands of microinjections.)

This had all been done before, and this had failed before. Where Mi and his team succeeded was using a concept called “localization.” Localization involves narrowing in on a very specific location in a genome. For this experiment, the team from Donghua University developed a “minimal basic structure model” of silkworm silk, which guided the genetic modifications. They wanted to make sure they had the exactly right transgenic spider silk proteins. Mi said that combining localization with this basic structure model “represents a significant departure from previous research.” And, judging only from the results, he might be right. Their “fibers exhibited impressive tensile strength (1,299 MPa) and toughness (319 MJ/m3), surpassing Kevlar’s toughness 6-fold.”

A world of super-materials

Mi’s research represents the bursting of a barrier. It opens up hugely important avenues for future biomimetic materials. As Mi puts it, “This groundbreaking achievement effectively resolves the scientific, technical, and engineering challenges that have hindered the commercialization of spider silk, positioning it as a viable alternative to commercially synthesized fibers like nylon and contributing to the advancement of ecological civilization.”

Around 60 percent of our clothing is made from synthetic fibers like nylon, polyester, and acrylic. These plastics are useful, but often bad for the environment. They shed into our waterways and sometimes damage wildlife. The production of these fibers is a source of greenhouse gas emissions. Now, we have a “sustainable, eco-friendly high-strength and ultra-tough alternative.” We can have silkworms creating silk six times as tough as Kevlar and ten times as strong as nylon.

We shouldn’t get carried away. This isn’t going to transform the textiles industry overnight. Gene-edited silkworms are still only going to produce a comparatively small amount of silk – even if farmed in the millions. But, as Mi himself concedes, this is only the beginning. If Mi’s localization and structure-model techniques are as remarkable as they seem, then this opens up the door to a great many supermaterials.

Nature continues to inspire. We had the bird, the gecko, and the shark. Now we have the spider-silkworm. What new secrets will we unravel in the future? And in what exciting ways will it change the world?

This article originally appeared on Freethink, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.