Food Poisoning Outbreaks Are Still A Problem. Powerful Tech Is Fighting Back.

The latest tools, like whole genome sequencing, are allowing food outbreaks to be identified and stopped more quickly.

With the pandemic at the forefront of everyone's minds, many people have wondered if food could be a source of coronavirus transmission. Luckily, that "seems unlikely," according to the CDC, but foodborne illnesses do still sicken a whopping 48 million people per year.

Whole genome sequencing is like "going from an eight-bit image—maybe like what you would see in Minecraft—to a high definition image."

In normal times, when there isn't a historic global health crisis infecting millions and affecting the lives of billions, foodborne outbreaks are real and frightening, potentially deadly, and can cause widespread fear of particular foods. Think of Romaine lettuce spreading E. coli last year— an outbreak that infected more than 500 people and killed eight—or peanut butter spreading salmonella in 2008, which infected 167 people.

The technologies available to detect and prevent the next foodborne disease outbreak have improved greatly over the past 30-plus years, particularly during the past decade, and better, more nimble technologies are being developed, according to experts in government, academia, and private industry. The key to advancing detection of harmful foodborne pathogens, they say, is increasing speed and portability of detection, and the precision of that detection.

Getting to Rapid Results

Researchers at Purdue University have recently developed a lateral flow assay that, with the help of a laser, can detect toxins and pathogenic E. coli. Lateral flow assays are cheap and easy to use; a good example is a home pregnancy test. You place a liquid or liquefied sample on a piece of paper designed to detect a single substance and soon after you get the results in the form of a colored line: yes or no.

"They're a great portable tool for us for food contaminant detection," says Carmen Gondhalekar, a fifth-year biomedical engineering graduate student at Purdue. "But one of the areas where paper-based lateral flow assays could use improvement is in multiplexing capability and their sensitivity."

J. Paul Robinson, a professor in Purdue's Colleges of Veterinary Medicine and Engineering, and Gondhalekar's advisor, agrees. "One of the fundamental problems that we have in detection is that it is hard to identify pathogens in complex samples," he says.

When it comes to foodborne disease outbreaks, you don't always know what substance you're looking for, so an assay made to detect only a single substance isn't always effective. The goal of the project at Purdue is to make assays that can detect multiple substances at once.

These assays would be more complex than a pregnancy test. As detailed in Gondhalekar's recent paper, a laser pulse helps create a spectral signal from the sample on the assay paper, and the spectral signal is then used to determine if any unique wavelengths associated with one of several toxins or pathogens are present in the sample. Though the handheld technology has yet to be built, the idea is that the results would be given on the spot. So someone in the field trying to track the source of a Salmonella infection could, for instance, put a suspected lettuce sample on the assay and see if it has the pathogen on it.

"What our technology is designed to do is to give you a rapid assessment of the sample," says Robinson. "The goal here is speed."

Seeing the Pathogen in "High-Def"

"One in six Americans will get a foodborne illness every year," according to Dr. Heather Carleton, a microbiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Enteric Diseases Laboratory Branch. But not every foodborne outbreak makes the news. In 2017 alone, the CDC monitored between 18 and 37 foodborne poison clusters per week and investigated 200 multi-state clusters. Hardboiled eggs, ground beef, chopped salad kits, raw oysters, frozen tuna, and pre-cut melon are just a taste of the foods that were investigated last year for different strains of listeria, salmonella, and E. coli.

At the heart of the CDC investigations is PulseNet, a national network of laboratories that uses DNA fingerprinting to detect outbreaks at local and regional levels. This is how it works: When a patient gets sick—with symptoms like vomiting and fever, for instance—they will go to a hospital or clinic for treatment. Since we're talking about foodborne illnesses, a clinician will likely take a stool sample from the patient and send it off to a laboratory to see if there is a foodborne pathogen, like salmonella, E. Coli, or another one. If it does contain a potentially harmful pathogen, then a bacterial isolate of that identified sample is sent to a regional public health lab so that whole genome sequencing can be performed.

Whole genome sequencing can differentiate "virtually all" strains of foodborne pathogens, no matter the species, according to the FDA.

Whole genome sequencing is a method for reading the entire genome of a bacterial isolate (or from any organism, for that matter). Instead of working with a couple dozen data points, now you're working with millions of base pairs. Carleton likes to describe it as "going from an eight-bit image—maybe like what you would see in Minecraft—to a high definition image," she says. "It's really an evolution of how we detect foodborne illnesses and identify outbreaks."

If the bacterial isolate matches another in the CDC's database, this means there could be a potential outbreak and an investigation may be started, with the goal of tracking the pathogen to its source.

Whole genome sequencing has been a relatively recent shift in foodborne disease detection. For more than 20 years, the standard technique for analyzing pathogens in foodborne disease outbreaks was pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. This method creates a DNA fingerprint for each sample in the form of a pattern of about 15-30 "bands," with each band representing a piece of DNA. Researchers like Carleton can use this fingerprint to see if two samples are from the same bacteria. The problem is that 15-30 bands are not enough to differentiate all isolates. Some isolates whose bands look very similar may actually come from different sources and some whose bands look different may be from the same source. But if you can see the entire DNA fingerprint, then you don't have that issue. That's where whole genome sequencing comes in.

Although the PulseNet team had piloted whole genome sequencing as early as 2013, it wasn't until July of last year that the transition to using whole genome sequencing for all pathogens was complete. Though whole genome sequencing requires far more computing power to generate, analyze, and compare those millions of data points, the payoff is huge.

Stopping Outbreaks Sooner

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) acquired their first whole genome sequencers in 2008, according to Dr. Eric Brown, the Director of the Division of Microbiology in the FDA's Office of Regulatory Science. Since then, through their GenomeTrakr program, a network of more than 60 domestic and international labs, the FDA has sequenced and publicly shared more than 400,000 isolates. "The impact of what whole genome sequencing could do to resolve a foodborne outbreak event was no less impactful than when NASA turned on the Hubble Telescope for the first time," says Brown.

Whole genome sequencing has helped identify strains of Salmonella that prior methods were unable to differentiate. In fact, whole genome sequencing can differentiate "virtually all" strains of foodborne pathogens, no matter the species, according to the FDA. This means it takes fewer clinical cases—fewer sick people—to detect and end an outbreak.

And perhaps the largest benefit of whole genome sequencing is that these detailed sequences—the millions of base pairs—can imply geographic location. The genomic information of bacterial strains can be different depending on the area of the country, helping these public health agencies eventually track the source of outbreaks—a restaurant, a farm, a food-processing center.

Coming Soon: "Lab in a Backpack"

Now that whole genome sequencing has become the go-to technology of choice for analyzing foodborne pathogens, the next step is making the process nimbler and more portable. Putting "the lab in a backpack," as Brown says.

The CDC's Carleton agrees. "Right now, the sequencer we use is a fairly big box that weighs about 60 pounds," she says. "We can't take it into the field."

A company called Oxford Nanopore Technologies is developing handheld sequencers. Their devices are meant to "enable the sequencing of anything by anyone anywhere," according to Dan Turner, the VP of Applications at Oxford Nanopore.

"The sooner that we can see linkages…the sooner the FDA gets in action to mitigate the problem and put in some kind of preventative control."

"Right now, sequencing is very much something that is done by people in white coats in laboratories that are set up for that purpose," says Turner. Oxford Nanopore would like to create a new, democratized paradigm.

The FDA is currently testing these types of portable sequencers. "We're very excited about it. We've done some pilots, to be able to do that sequencing in the field. To actually do it at a pond, at a river, at a canal. To do it on site right there," says Brown. "This, of course, is huge because it means we can have real-time sequencing capability to stay in step with an actual laboratory investigation in the field."

"The timeliness of this information is critical," says Marc Allard, a senior biomedical research officer and Brown's colleague at the FDA. "The sooner that we can see linkages…the sooner the FDA gets in action to mitigate the problem and put in some kind of preventative control."

At the moment, the world is rightly focused on COVID-19. But as the danger of one virus subsides, it's only a matter of time before another pathogen strikes. Hopefully, with new and advancing technology like whole genome sequencing, we can stop the next deadly outbreak before it really gets going.

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

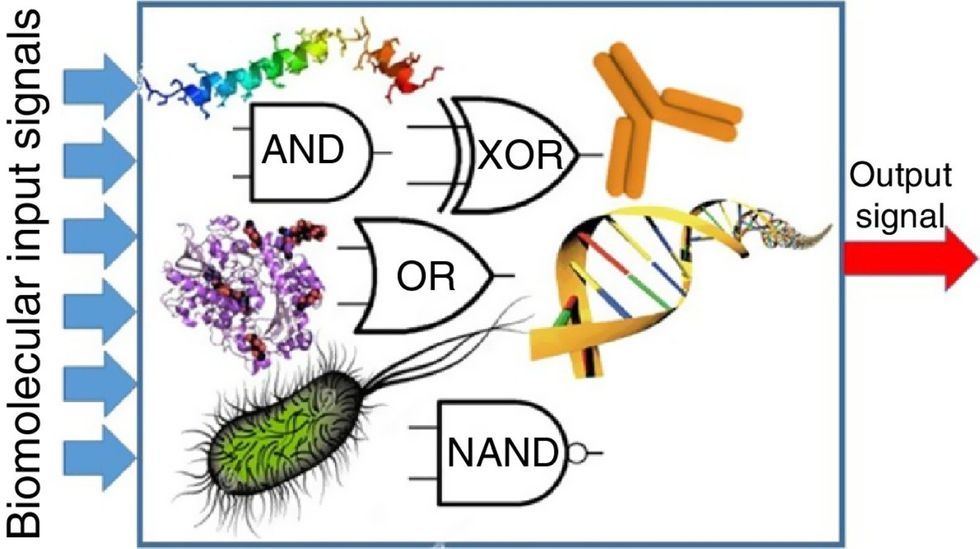

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.