Genome Reading and Editing Tools for All

An open book representing the ability to read the human genome.

In 2006, the cover of Scientific American was "Know Your DNA" and the inside story was "Genomes for All." Today, we are closer to that goal than ever. Making it affordable for everyone to understand and change their DNA will fundamentally alter how we manage diseases, how we conduct clinical research, and even how we select a mate.

A frequent line of questions on the topic of making genome reading affordable is: Do we need to read the whole genome in order to accurately predict disease risk?

Since 2006, we have driven the cost of reading a human genome down from $3 billion to $600. To aid interpretation and research to produce new diagnostics and therapeutics, my research team at Harvard initiated the Personal Genome Project and later, Openhumans.org. This has demonstrated international informed consent for human genomes, and diverse environmental and trait data can be distributed freely. This is done with no strings attached in a manner analogous to Wikipedia. Cell lines from that project are similarly freely available for experiments on synthetic biology, gene therapy and human developmental biology. DNA from those cells have been chosen by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology and the Food and Drug Administration to be the key federal standards for the human genome.

A frequent line of questions on the topic of making genome reading affordable is: Do we need to read the whole genome in order to accurately predict disease risk? Can we just do most commonly varying parts of the genome, which constitute only a tiny fraction of a percent? Or just the most important parts encoding the proteins or 'exome,' which constitute about one percent of the genome? The commonly varying parts of the genome are poor predictors of serious genetic diseases and the exomes don't detect DNA rearrangements which often wipe out gene function when they occur in non-coding regions within genes. Since the cost of the exome is not one percent of the whole genome cost, but nearly identical ($600), missing an impactful category of mutants is really not worth it. So the answer is yes, we should read the whole genome to glean comprehensively meaningful information.

In parallel to the reading revolution, we have dropped the price of DNA synthesis by a similar million-fold and made genome editing tools close to free.

WRITING

In parallel to the reading revolution, we have dropped the price of DNA synthesis by a similar million-fold and made genome editing tools like CRISPR, TALE and MAGE close to free by distributing them through the non-profit Addgene.org. Gene therapies are already curing blindness in children and cancer in adults, and hopefully soon infectious diseases and hemoglobin diseases like sickle cell anemia. Nevertheless, gene therapies are (so far) the most expensive class of drugs in history (about $1 million dollars per dose).

This is in large part because the costs of proving safety and efficacy in a randomized clinical trial are high and that cost is spread out only over the people that benefit (aka the denominator). Striking growth is evident in such expensive hyper-personalized therapies ever since the "Orphan Drug Act of 1983." For the most common disease, aging (which kills 90 percent of people in wealthy regions of the world), the denominator is maximal and the cost of the drugs should be low as genetic interventions to combat aging become available in the next ten years. But what can we do about rarer diseases with cheap access to genome reading and editing tools? Try to prevent them in the first place.

A huge fraction of these births is preventable if unaffected carriers of such diseases do not mate.

ARITHMETIC

While the cost of reading has plummeted, the value of knowing your genome is higher than ever. About 5 percent of births result in extreme medical trauma over a person's lifetime due to rare genetic diseases. Even without gene therapy, these cost the family and society more than a million dollars in drugs, diagnostics and instruments, extra general care, loss of income for the affected individual and other family members, plus pain and anxiety of the "medical odyssey" often via dozens of mystified physicians. A huge fraction of these births is preventable if unaffected carriers of such diseases do not mate.

The non-profit genetic screening organization, Dor Yeshorim (established in 1983), has shown that this is feasible by testing for Tay–Sachs disease, Familial dysautonomia, Cystic fibrosis, Canavan disease, Glycogen storage disease (type 1), Fanconi anemia (type C), Bloom syndrome, Niemann–Pick disease, Mucolipidosis type IV. This is often done at the pre-marital, matchmaking phase, which can reduce the frequency of natural or induced abortions. Such matchmaking can be done in such a way that no one knows the carrier status of any individual in the system. In addition to those nine tests, many additional diseases can be picked up by whole genome sequencing. No person can know in advance that they are exempt from these risks.

Furthermore, concerns about rare "false positives" is far less at the stage of matchmaking than at the stage of prenatal testing, since the latter could involve termination of a healthy fetus, while the former just means that you restrict your dating to 90 percent of the population. In order to scale this up from 13 million Ashkenazim and Sephardim to billions in diverse cultures, we will likely see new computer security, encryption, blockchain and matchmaking tools.

Once the diseases are eradicated from our population, the interventions can be said to impact not only the current population, but all subsequent generations.

THE FUTURE

As reading and writing become exponentially more affordable and reliable, we can tackle equitable distribution, but there remain issues of education and security. Society, broadly (insurers, health care providers, governments) should be able to see a roughly 12-fold return on their investment of $1800 per person ($600 each for raw data, interpretation and incentivizing the participant) by saving $1 million per diseased child per 20 families. Everyone will have free access to their genome information and software to guide their choices in precision medicines, mates and participation in biomedical research studies.

In terms of writing and editing, if delivery efficiency and accuracy keep improving, then pill or aerosol formulations of gene therapies -- even non-prescription, veterinary or home-made versions -- are not inconceivable. Preventions tends to be more affordable and more humane than cures. If gene therapies provide prevention of diseases of aging, cancer and cognitive decline, they might be considered "enhancement," but not necessarily more remarkable than past preventative strategies, like vaccines against HPV-cancer, smallpox and polio. Whether we're overcoming an internal genetic flaw or an external infectious disease, the purpose is the same: to minimize human suffering. Once the diseases are eradicated from our population, the interventions can be said to impact not only the current population, but all subsequent generations. This reminds us that we need to listen carefully, educate each other and proactively imagine and deflect likely, and even unlikely, unintended consequences, including stigmatization of the last few unprotected individuals.

Scientists are making machines, wearable and implantable, to act as kidneys

Recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen soon.

Like all those whose kidneys have failed, Scott Burton’s life revolves around dialysis. For nearly two decades, Burton has been hooked up (or, since 2020, has hooked himself up at home) to a dialysis machine that performs the job his kidneys normally would. The process is arduous, time-consuming, and expensive. Except for a brief window before his body rejected a kidney transplant, Burton has depended on machines to take the place of his kidneys since he was 12-years-old. His whole life, the 39-year-old says, revolves around dialysis.

“Whenever I try to plan anything, I also have to plan my dialysis,” says Burton says, who works as a freelance videographer and editor. “It’s a full-time job in itself.”

Many of those on dialysis are in line for a kidney transplant that would allow them to trade thrice-weekly dialysis and strict dietary limits for a lifetime of immunosuppressants. Burton’s previous transplant means that his body will likely reject another donated kidney unless it matches perfectly—something he’s not counting on. It’s why he’s enthusiastic about the development of artificial kidneys, small wearable or implantable devices that would do the job of a healthy kidney while giving users like Burton more flexibility for traveling, working, and more.

Still, the devices aren’t ready for testing in humans—yet. But recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen soon, according to Jonathan Himmelfarb, a nephrologist at the University of Washington.

“It would liberate people with kidney failure,” Himmelfarb says.

An engineering marvel

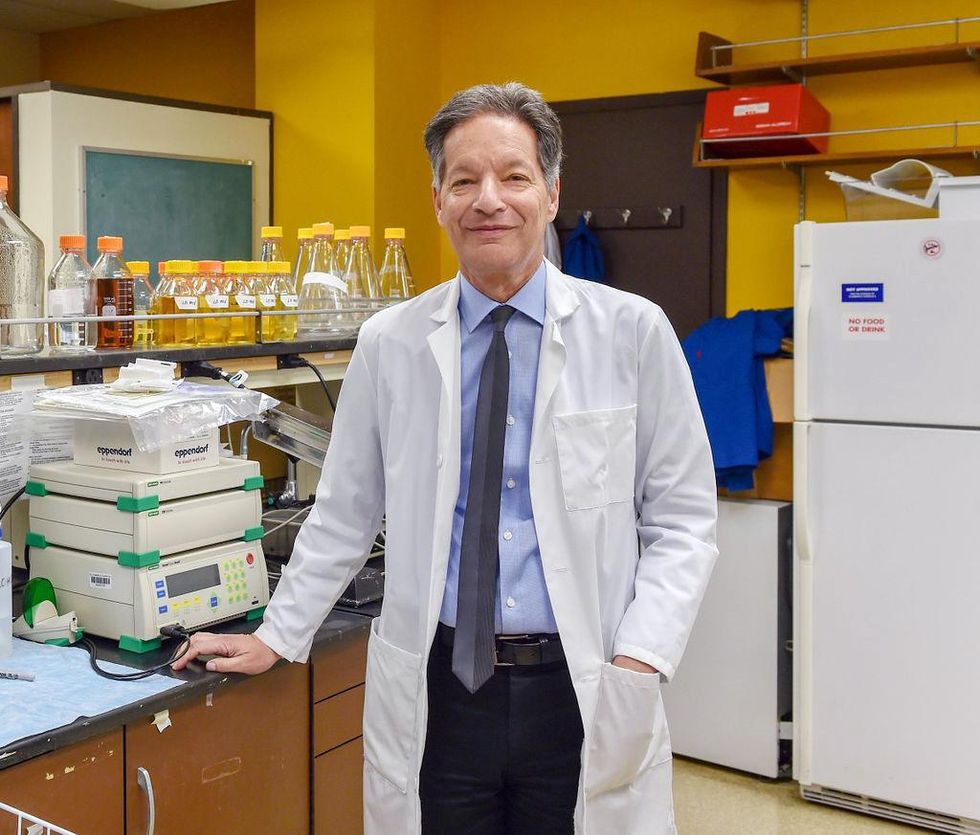

Compared to the heart or the brain, the kidney doesn’t get as much respect from the medical profession, but its job is far more complex. “It does hundreds of different things,” says UCLA’s Ira Kurtz.

Kurtz would know. He’s worked as a nephrologist for 37 years, devoting his career to helping those with kidney disease. While his colleagues in cardiology and endocrinology have seen major advances in the development of artificial hearts and insulin pumps, little has changed for patients on hemodialysis. The machines remain bulky and require large volumes of a liquid called dialysate to remove toxins from a patient’s blood, along with gallons of purified water. A kidney transplant is the next best thing to someone’s own, functioning organ, but with over 600,000 Americans on dialysis and only about 100,000 kidney transplants each year, most of those in kidney failure are stuck on dialysis.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. To build an artificial heart, Kurtz says, you basically need to engineer a pump. An artificial pancreas needs to balance blood sugar levels with insulin secretion. While neither of these tasks is simple, they are fairly straightforward. The kidney, on the other hand, does more than get rid of waste products like urea and other toxins. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different, helping to regulate electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and phosphorous; maintaining blood pressure and water balance; guiding the body’s hormonal and inflammatory responses; and aiding in the formation of red blood cells.

There's been little progress for patients during Ira Kurtz's 37 years as a nephrologist. Artificial kidneys would change that.

UCLA

Dialysis primarily filters waste, and does so well enough to keep someone alive, but it isn’t a true artificial kidney because it doesn’t perform the kidney’s other jobs, according to Kurtz, such as sensing levels of toxins, wastes, and electrolytes in the blood. Due to the size and water requirements of existing dialysis machines, the equipment isn’t portable. Physicians write a prescription for a certain duration of dialysis and assess how well it’s working with semi-regular blood tests. The process of dialysis itself, however, is conducted blind. Doctors can’t tell how much dialysis a patient needs based on kidney values at the time of treatment, says Meera Harhay, a nephrologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

But it’s the impact of dialysis on their day-to-day lives that creates the most problems for patients. Only one-quarter of those on dialysis are able to remain employed (compared to 85% of similar-aged adults), and many report a low quality of life. Having more flexibility in life would make a major different to her patients, Harhay says.

“Almost half their week is taken up by the burden of their treatment. It really eats away at their freedom and their ability to do things that add value to their life,” she says.

Art imitates life

The challenge for artificial kidney designers was how to compress the kidney’s natural functions into a portable, wearable, or implantable device that wouldn’t need constant access to gallons of purified and sterilized water. The other universal challenge they faced was ensuring that any part of the artificial kidney that would come in contact with blood was kept germ-free to prevent infection.

As part of the 2021 KidneyX Prize, a partnership between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the American Society of Nephrology, inventors were challenged to create prototypes for artificial kidneys. Himmelfarb’s team at the University of Washington’s Center for Dialysis Innovation won the prize by focusing on miniaturizing existing technologies to create a portable dialysis machine. The backpack sized AKTIV device (Ambulatory Kidney to Increase Vitality) will recycle dialysate in a closed loop system that removes urea from blood and uses light-based chemical reactions to convert the urea to nitrogen and carbon dioxide, which allows the dialysate to be recirculated.

Himmelfarb says that the AKTIV can be used when at home, work, or traveling, which will give users more flexibility and freedom. “If you had a 30-pound device that you could put in the overhead bins when traveling, you could go visit your grandkids,” he says.

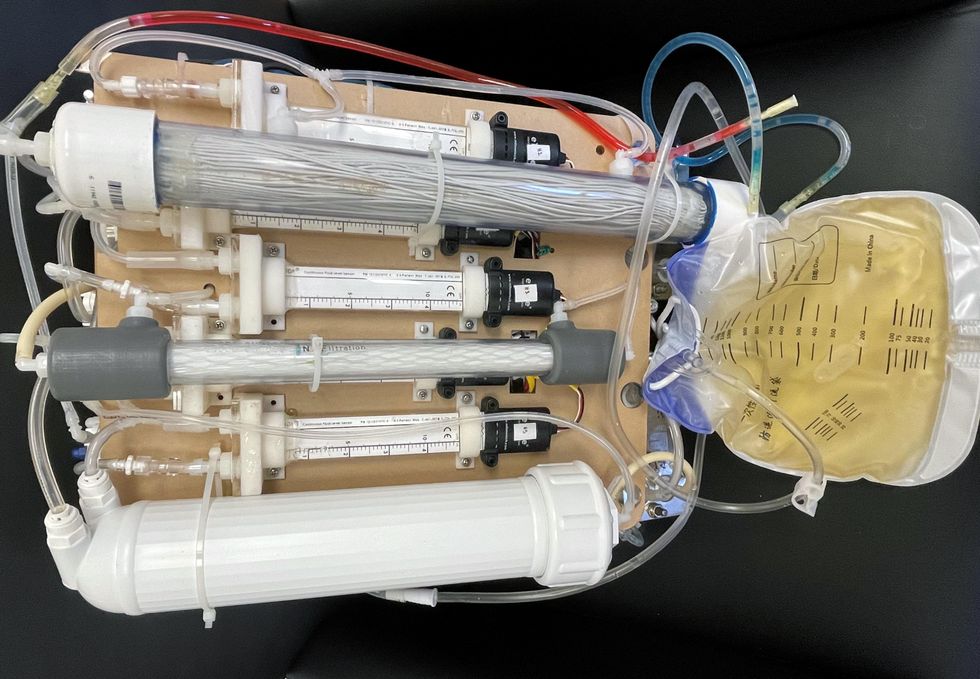

Kurtz’s team at UCLA partnered with the U.S. Kidney Research Corporation and Arkansas University to develop a dialysate-free desktop device (about the size of a small printer) as the first phase of a progression that will he hopes will lead to something small and implantable. Part of the reason for the artificial kidney’s size, Kurtz says, is the number of functions his team are cramming into it. Not only will it filter urea from blood, but it will also use electricity to help regulate electrolyte levels in a process called electrodeionization. Kurtz emphasizes that these additional functions are what makes his design a true artificial kidney instead of just a small dialysis machine.

One version of an artificial kidney.

UCLA

“It doesn't have just a static function. It has a bank of sensors that measure chemicals in the blood and feeds that information back to the device,” Kurtz says.

Other startups are getting in on the game. Nephria Bio, a spinout from the South Korean-based EOFlow, is working to develop a wearable dialysis device, akin to an insulin pump, that uses miniature cartridges with nanomaterial filters to clean blood (Harhay is a scientific advisor to Nephria). Ian Welsford, Nephria’s co-founder and CTO, says that the device’s design means that it can also be used to treat acute kidney injuries in resource-limited settings. These potentials have garnered interest and investment in artificial kidneys from the U.S. Department of Defense.

For his part, Burton is most interested in an implantable device, as that would give him the most freedom. Even having a regular outpatient procedure to change batteries or filters would be a minor inconvenience to him.

“Being plugged into a machine, that’s not mimicking life,” he says.

This article was first published by Leaps.org on May 5, 2022.

With this new technology, hospitals and pharmacies could make vaccines and medicines onsite

New research focuses on methods that could change medicine-making worldwide. The scientists propose bursting cells open, removing their DNA and using the cellular gears inside to make therapies.

Most modern biopharmaceutical medicines are produced by workhorse cells—typically bacterial but sometimes mammalian. The cells receive the synthesizing instructions on a snippet of a genetic code, which they incorporate into their DNA. The cellular machinery—ribosomes, RNAs, polymerases, and other compounds—read and use these instructions to build the medicinal molecules, which are harvested and administered to patients.

Although a staple of modern pharma, this process is complex and expensive. One must first insert the DNA instructions into the cells, which they may or may not uptake. One then must grow the cells, keeping them alive and well, so that they produce the required therapeutics, which then must be isolated and purified. To make this at scale requires massive bioreactors and big factories from where the drugs are distributed—and may take a while to arrive where they’re needed. “The pandemic showed us that this method is slow and cumbersome,” says Govind Rao, professor of biochemical engineering who directs the Center for Advanced Sensor Technology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). “We need better methods that can work faster and can work locally where an outbreak is happening.”

Rao and his team of collaborators, which spans multiple research institutions, believe they have a better approach that may change medicine-making worldwide. They suggest forgoing the concept of using living cells as medicine-producers. Instead, they propose breaking the cells and using the remaining cellular gears for assembling the therapeutic compounds. Instead of inserting the DNA into living cells, the team burst them open, and removed their DNA altogether. Yet, the residual molecular machinery of ribosomes, polymerases and other cogwheels still functioned the way it would in a cell. “Now if you drop your DNA drug-making instructions into that soup, this machinery starts making what you need,” Rao explains. “And because you're no longer worrying about living cells, it becomes much simpler and more efficient.” The collaborators detail their cell-free protein synthesis or CFPS method in their recent paper published in preprint BioAxiv.

While CFPS does not use living cells, it still needs the basic building blocks to assemble proteins from—such as amino acids, nucleotides and certain types of enzymes. These are regularly added into this “soup” to keep the molecular factory chugging. “We just mix everything in as a batch and we let it integrate,” says James Robert Swartz, professor of chemical engineering and bioengineering at Stanford University and co-author of the paper. “And we make sure that we provide enough oxygen.” Rao likens the process to making milk from milk powder.

For a variety of reasons—from the field’s general inertia to regulatory approval hurdles—the method hasn’t become mainstream. The pandemic rekindled interest in medicines that can be made quickly and easily, so it drew more attention to the technology.

The idea of a cell-free protein synthesis is older than one might think. Swartz first experimented with it around 1997, when he was a chemical engineer at Genentech. While working on engineering bacteria to make pharmaceuticals, he discovered that there was a limit to what E. coli cells, the workhorse darling of pharma, could do. For example, it couldn’t grow and properly fold some complex proteins. “We tried many genetic engineering approaches, many fermentation, development, and environmental control approaches,” Swartz recalls—to no avail.

“The organism had its own agenda,” he quips. “And because everything was happening within the organism, we just couldn't really change those conditions very easily. Some of them we couldn’t change at all—we didn’t have control.”

It was out of frustration with the defiant bacteria that a new idea took hold. Could the cells be opened instead, so that the protein-forming reactions could be influenced more easily? “Obviously, we’d lose the ability for them to reproduce,” Swartz says. But that also meant that they no longer needed to keep the cells alive and could focus on making the specific reactions happen. “We could take the catalysts, the enzymes, and the more complex catalysts and activate them, make them work together, much as they would in a living cell, but the way we wanted.”

In 1998, Swartz joined Stanford, and began perfecting the biochemistry of the cell-free method, identifying the reactions he wanted to foster and stopping those he didn’t want. He managed to make the idea work, but for a variety of reasons—from the field’s general inertia to regulatory approval hurdles—the method hasn’t become mainstream. The pandemic rekindled interest in medicines that can be made quickly and easily, so it drew more attention to the technology. For their BioArxiv paper, the team tested the method by growing a specific antiviral protein called griffithsin.

First identified by Barry O’Keefe at National Cancer Institute over a decade ago, griffithsin is an antiviral known to interfere with many viruses’ ability to enter cells—including HIV, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, MERS and others. Originally isolated from the red algae Griffithsia, it works differently from antibodies and antibody cocktails.

Most antiviral medicines tend to target the specific receptors that viruses use to gain entry to the cells they infect. For example, SARS-CoV-2 uses the infamous spike protein to latch onto the ACE2 receptor of mammalian cells. The antibodies or other antiviral molecules stick to the spike protein, shutting off its ability to cling onto the ACE2 receptors. Unfortunately, the spike proteins mutate very often, so the medicines lose their potency. On the contrary, griffithsin has the ability to cling to the different parts of viral shells called capsids—namely to the molecules of mannose, a type of sugar. That extra stuff, glued all around the capsid like dead weight, makes it impossible for the virus to squeeze into the cell.

“Every time we have a vaccine or an antibody against a specific SARS-CoV-2 strain, that strain then mutates and so you lose efficacy,” Rao explains. “But griffithsin molecules glom onto the viral capsid, so the capsid essentially becomes a sticky mess and can’t enter the cell.” Mannose molecules also don’t mutate as easily as viruses’ receptors, so griffithsin-based antivirals do not have to be constantly updated. And because mannose molecules are found on many viruses’ capsids, it makes griffithsin “a universal neutralizer,” Rao explains.

“When griffithsin was discovered, we recognized that it held a lot of promise as a potential antiviral agent,” O’Keefe says. In 2010, he published a paper about griffithsin efficacy in neutralizing viruses of the corona family—after the first SARS outbreak in the early 2000s, the scientific community was interested in such antivirals. Yet, griffithsin is still not available as an off-the-shelf product. So during the Covid pandemic, the team experimented with synthesizing griffithsin using the cell-free production method. They were able to generate potent griffithsin in less than 24 hours without having to grow living cells.

The antiviral protein isn't the only type of medicine that can be made cell-free. The proteins needed for vaccine production could also be made the same way. “Such portable, on-demand drug manufacturing platforms can produce antiviral proteins within hours, making them ideal for combating future pandemics,” Rao says. “We would be able to stop the pandemic before it spreads.”

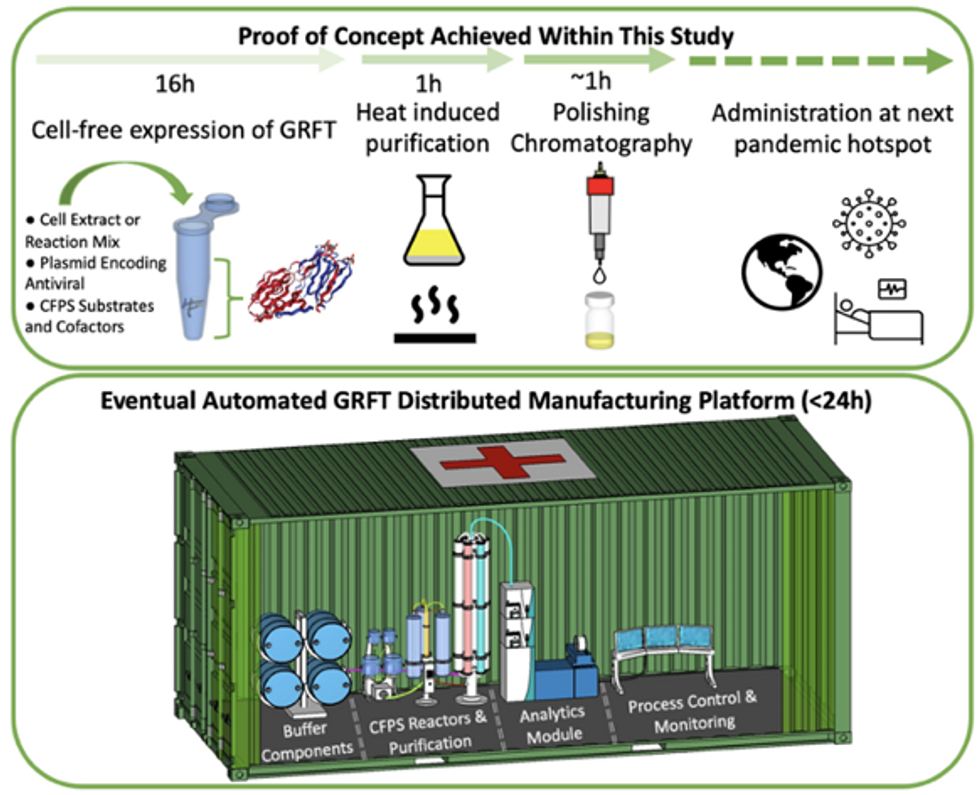

Top: Describes the process used in the study. Bottom: Describes how the new medicines and vaccines could be made at the site of a future viral outbreak.

Image courtesy of Rao and team, sourced from An approach to rapid distributed manufacturing of broad spectrumanti-viral griffithsin using cell-free systems to mitigate pandemics.

Rao’s idea is to perfect the technology to the point that any hospital or pharmacy can load up the media containing molecular factories, mix up the required amino acids, nucleotides and enzymes, and harvest the meds within hours. That will allow making medicines onsite and on demand. “That would be a self-contained production unit, so that you could just ship the production wherever the pandemic is breaking out,” says Swartz.

These units and the meds they produce, will, of course, have to undergo rigorous testing. “The biggest hurdles will be validating these against conventional technology,” Rao says. The biotech industry is risk-averse and prefers the familiar methods. But if this approach works, it may go beyond emergency situations and revolutionize the medicine-making paradigm even outside hospitals and pharmacies. Rao hopes that someday the method might become so mainstream that people may be able to buy and operate such reactors at home. “You can imagine a diabetic patient making insulin that way, or some other drugs,” Rao says. It would work not unlike making baby formula from the mere white powder. Just add water—and some oxygen, too.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.