How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

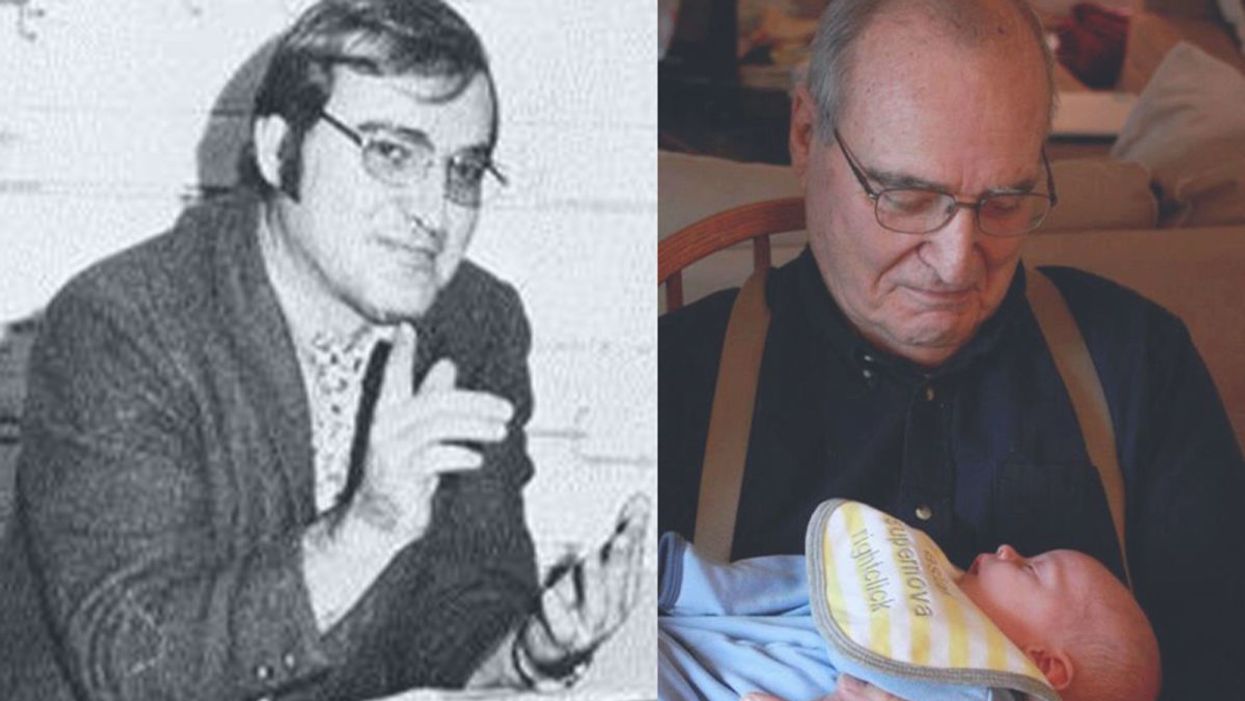

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

The large genetic studies underlying certain disease risk tests have primarily been done in populations of European ancestry, limiting their accuracy.

Earlier this year, California-based Ambry Genetics announced that it was discontinuing a test meant to estimate a person's risk of developing prostate or breast cancer. The test looks for variations in a person's DNA that are known to be associated with these cancers.

Known as a polygenic risk score, this type of test adds up the effects of variants in many genes — often in the dozens or hundreds — and calculates a person's risk of developing a particular health condition compared to other people. In this way, polygenic risk scores are different from traditional genetic tests that look for mutations in single genes, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, which raise the risk of breast cancer.

Traditional genetic tests look for mutations that are relatively rare in the general population but have a large impact on a person's disease risk, like BRCA1 and BRCA2. By contrast, polygenic risk scores scan for more common genetic variants that, on their own, have a small effect on risk. Added together, however, they can raise a person's risk for developing disease.

These scores could become a part of routine healthcare in the next few years. Researchers are developing polygenic risk scores for cancer, heart, disease, diabetes and even depression. Before they can be rolled out widely, they'll have to overcome a key limitation: racial bias.

"The issue with these polygenic risk scores is that the scientific studies which they're based on have primarily been done in individuals of European ancestry," says Sara Riordan, president of the National Society of Genetics Counselors. These scores are calculated by comparing the genetic data of people with and without a particular disease. To make these scores accurate, researchers need genetic data from tens or hundreds of thousands of people.

Myriad's old test would have shown that a Black woman had twice as high of a risk for breast cancer compared to the average woman even if she was at low or average risk.

A 2018 analysis found that 78% of participants included in such large genetic studies, known as genome-wide association studies, were of European descent. That's a problem, because certain disease-associated genetic variants don't appear equally across different racial and ethnic groups. For example, a particular variant in the TTR gene, known as V1221, occurs more frequently in people of African descent. In recent years, the variant has been found in 3 to 4 percent of individuals of African ancestry in the United States. Mutations in this gene can cause protein to build up in the heart, leading to a higher risk of heart failure. A polygenic risk score for heart disease based on genetic data from mostly white people likely wouldn't give accurate risk information to African Americans.

Accuracy in genetic testing matters because such polygenic risk scores could help patients and their doctors make better decisions about their healthcare.

For instance, if a polygenic risk score determines that a woman is at higher-than-average risk of breast cancer, her doctor might recommend more frequent mammograms — X-rays that take a picture of the breast. Or, if a risk score reveals that a patient is more predisposed to heart attack, a doctor might prescribe preventive statins, a type of cholesterol-lowering drug.

"Let's be clear, these are not diagnostic tools," says Alicia Martin, a population and statistical geneticist at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. "We can't use a polygenic score to say you will or will not get breast cancer or have a heart attack."

But combining a patient's polygenic risk score with other factors that affect disease risk — like age, weight, medication use or smoking status — may provide a better sense of how likely they are to develop a specific health condition than considering any one risk factor one its own. The accuracy of polygenic risk scores becomes even more important when considering that these scores may be used to guide medication prescription or help patients make decisions about preventive surgery, such as a mastectomy.

In a study published in September, researchers used results from large genetics studies of people with European ancestry and data from the UK Biobank to calculate polygenic risk scores for breast and prostate cancer for people with African, East Asian, European and South Asian ancestry. They found that they could identify individuals at higher risk of breast and prostate cancer when they scaled the risk scores within each group, but the authors say this is only a temporary solution. Recruiting more diverse participants for genetics studies will lead to better cancer detection and prevent, they conclude.

Recent efforts to do just that are expected to make these scores more accurate in the future. Until then, some genetics companies are struggling to overcome the European bias in their tests.

Acknowledging the limitations of its polygenic risk score, Ambry Genetics said in April that it would stop offering the test until it could be recalibrated. The company launched the test, known as AmbryScore, in 2018.

"After careful consideration, we have decided to discontinue AmbryScore to help reduce disparities in access to genetic testing and to stay aligned with current guidelines," the company said in an email to customers. "Due to limited data across ethnic populations, most polygenic risk scores, including AmbryScore, have not been validated for use in patients of diverse backgrounds." (The company did not make a spokesperson available for an interview for this story.)

In September 2020, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network updated its guidelines to advise against the use of polygenic risk scores in routine patient care because of "significant limitations in interpretation." The nonprofit, which represents 31 major cancer cancers across the United States, said such scores could continue to be used experimentally in clinical trials, however.

Holly Pederson, director of Medical Breast Services at the Cleveland Clinic, says the realization that polygenic risk scores may not be accurate for all races and ethnicities is relatively recent. Pederson worked with Salt Lake City-based Myriad Genetics, a leading provider of genetic tests, to improve the accuracy of its polygenic risk score for breast cancer.

The company announced in August that it had recalibrated the test, called RiskScore, for women of all ancestries. Previously, Myriad did not offer its polygenic risk score to women who self-reported any ancestry other than sole European or Ashkenazi ancestry.

"Black women, while they have a similar rate of breast cancer to white women, if not lower, had twice as high of a polygenic risk score because the development and validation of the model was done in white populations," Pederson said of the old test. In other words, Myriad's old test would have shown that a Black woman had twice as high of a risk for breast cancer compared to the average woman even if she was at low or average risk.

To develop and validate the new score, Pederson and other researchers assessed data from more than 275,000 women, including more than 31,000 African American women and nearly 50,000 women of East Asian descent. They looked at 56 different genetic variants associated with ancestry and 93 associated with breast cancer. Interestingly, they found that at least 95% of the breast cancer variants were similar amongst the different ancestries.

The company says the resulting test is now more accurate for all women across the board, but Pederson cautions that it's still slightly less accurate for Black women.

"It's not only the lack of data from Black women that leads to inaccuracies and a lack of validation in these types of risk models, it's also the pure genomic diversity of Africa," she says, noting that Africa is the most genetically diverse continent on the planet. "We just need more data, not only in American Black women but in African women to really further characterize that continent."

Martin says it's problematic that such scores are most accurate for white people because they could further exacerbate health disparities in traditionally underserved groups, such as Black Americans. "If we were to set up really representative massive genetic studies, we would do a much better job at predicting genetic risk for everybody," she says.

Earlier this year, the National Institutes of Health awarded $38 million to researchers to improve the accuracy of polygenic risk scores in diverse populations. Researchers will create new genome datasets and pool information from existing ones in an effort to diversify the data that polygenic scores rely on. They plan to make these datasets available to other scientists to use.

"By having adequate representation, we can ensure that the results of a genetic test are widely applicable," Riordan says.

New Podcast: George Church on Woolly Mammoths, Organ Transplants, and Covid Vaccines

Dr. George Church, a leading pioneer of gene editing, updates our listeners on several of his noteworthy projects.

The "Making Sense of Science" podcast features interviews with leading medical and scientific experts about the latest developments and the big ethical and societal questions they raise. This monthly podcast is hosted by journalist Kira Peikoff, founding editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

This month, our guest is notable genetics pioneer Dr. George Church of Harvard Medical School. Dr. Church has remarkably bold visions for how innovation in science can fundamentally transform the future of humanity and our planet. His current moonshot projects include: de-extincting some of the woolly mammoth's genes to create a hybrid Asian elephant with the cold-tolerance traits of the woolly mammoth, so that this animal can re-populate the Arctic and help stave off climate change; reversing chronic diseases of aging through gene therapy, which he and colleagues are now testing in dogs; and transplanting genetically engineered pig organs to humans to eliminate the tragically long waiting lists for organs. Hear Dr. Church discuss all this and more on our latest episode.

Watch the Trailer:

Listen to the Episode:

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.