How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

Want to Motivate Vaccinations? Message Optimism, Not Doom

There is a lot to be optimistic about regarding the new safe and highly effective vaccines, which are moving society closer toward the goal of close human contact once again.

After COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, life as we knew it altered dramatically and millions went into lockdown. Since then, most of the world has had to contend with masks, distancing, ventilation and cycles of lockdowns as surges flare up. Deaths from COVID-19 infection, along with economic and mental health effects from the shutdowns, have been devastating. The need for an ultimate solution -- safe and effective vaccines -- has been paramount.

On November 9, 2020 (just 8 months after the pandemic announcement), the press release for the first effective COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer/BioNTech was issued, followed by positive announcements regarding the safety and efficacy of five other vaccines from Moderna, University of Oxford/AztraZeneca, Novavax, Johnson and Johnson and Sputnik V. The Moderna and Pfizer vaccines have earned emergency use authorization through the FDA in the United States and are being distributed. We -- after many long months -- are seeing control of the devastating COVID-19 pandemic glimmering into sight.

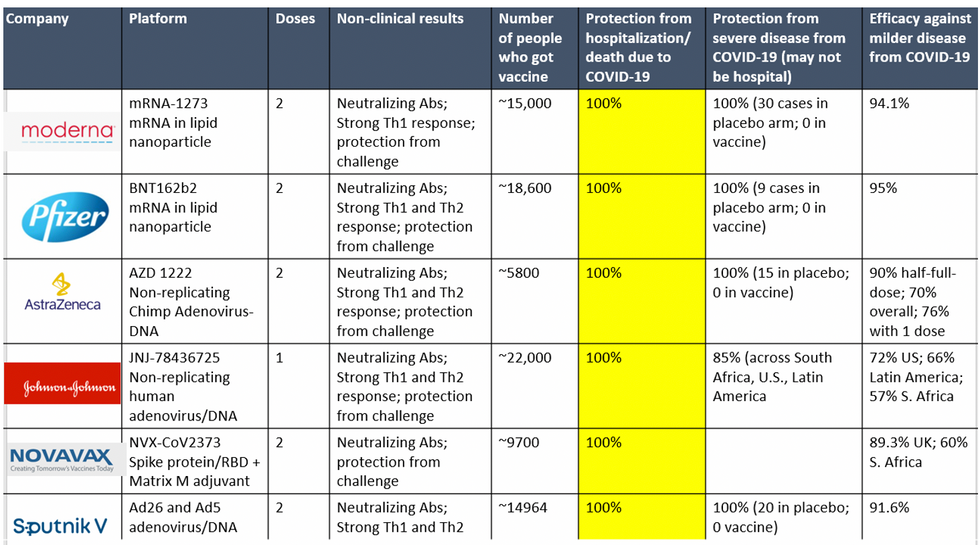

To be clear, these vaccine candidates for COVID-19, both authorized and not yet authorized, are highly effective and safe. In fact, across all trials and sites, all six vaccines were 100% effective in preventing hospitalizations and death from COVID-19.

All Vaccines' Phase 3 Clinical Data

Complete protection against hospitalization and death from COVID-19 exhibited by all vaccines with phase 3 clinical trial data.

This astounding level of protection from SARS-CoV-2 from all vaccine candidates across multiple regions is likely due to robust T cell response from vaccination and will "defang" the virus from the concerns that led to COVID-19 restrictions initially: the ability of the virus to cause severe illness. This is a time of hope and optimism. After the devastating third surge of COVID-19 infections and deaths over the winter, we finally have an opportunity to stem the crisis – if only people readily accept the vaccines.

Amidst these incredible scientific advancements, however, public health officials and politicians have been pushing downright discouraging messaging. The ubiquitous talk of ongoing masks and distancing restrictions without any clear end in sight threatens to dampen uptake of the vaccines. It's imperative that we break down each concern and see if we can revitalize our public health messaging accordingly.

The first concern: we currently do not know if the vaccines block asymptomatic infection as well as symptomatic disease, since none of the phase 3 vaccine trials were set up to answer this question. However, there is biological plausibility that the antibodies and T-cell responses blocking symptomatic disease will also block asymptomatic infection in the nasal passages. IgG immunoglobulins (generated and measured by the vaccine trials) enter the nasal mucosa and systemic vaccinations generate IgA antibodies at mucosal surfaces. Monoclonal antibodies given to outpatients with COVID-19 hasten viral clearance from the airways.

Although it is prudent for those who are vaccinated to wear masks around the unvaccinated in case a slight risk of transmission remains, two fully vaccinated people can comfortably abandon masking around each other.

Moreover, data from the AztraZeneca trial (including in the phase 3 trial final results manuscript), where weekly self-swabbing was done by participants, and data from the Moderna trial, where a nasal swab was performed prior to the second dose, both showed risk reductions in asymptomatic infection with even a single dose. Finally, real-world data from a large Pfizer-based vaccine campaign in Israel shows a 50% reduction in infections (asymptomatic or symptomatic) after just the first dose.

Therefore, the likelihood of these vaccines blocking asymptomatic carriage, as well as symptomatic disease, is high. Although it is prudent for those who are vaccinated to wear masks around the unvaccinated in case a slight risk of transmission remains, two fully vaccinated people can comfortably abandon masking around each other. Moreover, as the percentage of vaccinated people increases, it will be increasingly untenable to impose restrictions on this group. Once herd immunity is reached, these restrictions can and should be abandoned altogether.

The second concern translating to "doom and gloom" messaging lately is around the identification of troubling new variants due to enhanced surveillance via viral sequencing. Four major variants circulating at this point (with others described in the past) are the B.1.1.7 variant ("UK variant"), B.1.351 ("South Africa variant), P.1. ("Brazil variant"), and the L452R variant identified in California. Although the UK variant is likely to be more transmissible, as is the South Africa variant, we have no reason to believe that masks, distancing and ventilation are ineffective against these variants.

Moreover, neutralizing antibody titers with the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines do not seem to be significantly reduced against the variants. Finally, although the Novavax 2-dose and Johnson and Johnson (J&J) 1-dose vaccines had lower rates of efficacy against moderate COVID-19 disease in South Africa, their efficacy against severe disease was impressively high. In fact J&J's vaccine still prevented 100% of hospitalizations and death from COVID-19. When combining both hospitalizations/deaths and severe symptoms managed at home, the J&J 1-dose vaccine was 85% protective across all three sites of the trial: the U.S., Latin America (including Brazil), and South Africa.

In South Africa, nearly all cases of COVID-19 (95%) were due to infection with the B.1.351 SARS-CoV-2 variant. Finally, since herd immunity does not rely on maximal immune responses among all individuals in a society, the Moderna/Pfizer/J&J vaccines are all likely to achieve that goal against variants. And thankfully, all of these vaccines can be easily modified to boost specifically against a new variant if needed (indeed, Moderna and Pfizer are already working on boosters against the prominent variants).

The third concern of some public health officials is that people will abandon all restrictions once vaccinated unless overly cautious messages are drilled into them. Indeed, the false idea that if you "give people an inch, they will take a mile" has been misinforming our messaging about mitigation since the beginning of the pandemic. For example, the very phrase "stay at home" with all of its non-applicability for essential workers and single individuals is stigmatizing and unrealistic for many. Instead, the message should have focused on how people can additively reduce their risks under different circumstances.

The public will be more inclined to trust health officials if those officials communicate with nuanced messages backed up by evidence, rather than with broad brushstrokes that shame. Therefore, we should be saying that "vaccinated people can be together with other vaccinated individuals without restrictions but must protect the unvaccinated with masks and distancing." And we can say "unvaccinated individuals should adhere to all current restrictions until vaccinated" without fear of misunderstandings. Indeed, this kind of layered advice has been communicated to people living with HIV and those without HIV for a long time (if you have HIV but partner does not, take these precautions; if both have HIV, you can do this, etc.).

Our heady progress in vaccine development, along with the incredible efficacy results of all of them, is unprecedented. However, we are at risk of undermining such progress if people balk at the vaccine because they don't believe it will make enough of a difference. One of the most critical messages we can deliver right now is that these vaccines will eventually free us from the restrictions of this pandemic. Let's use tiered messaging and clear communication to boost vaccine optimism and uptake, and get us to the goal of close human contact once again.

Inside Scoop: How a DARPA Scientist Helped Usher in a Game-Changing Covid Treatment

Amy Jenkins is a program manager for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency's Biological Technologies Office, which runs a project called the Pandemic Prevention Platform.

Amy Jenkins was in her office at DARPA, a research and development agency within the Department of Defense, when she first heard about a respiratory illness plaguing the Chinese city of Wuhan. Because she's a program manager for DARPA's Biological Technologies Office, her colleagues started stopping by. "It's really unusual, isn't it?" they would say.

At the time, China had a few dozen cases of what we now call COVID-19. "We should maybe keep an eye on that," she thought.

Early in 2020, still just keeping watch, she was visiting researchers working on DARPA's Pandemic Prevention Platform (P3), a project to develop treatments for "any known or previously unknown infectious threat," within 60 days of its appearance. "We looked at each other and said, 'Should we be doing something?'" she says.

For projects like P3, groups of scientists—often at universities and private companies—compete for DARPA contracts, and program managers like Jenkins oversee the work. Those that won the P3 bid included scientists at AbCellera Biologics, Inc., AstraZeneca, Duke University, and Vanderbilt University.

At the time Jenkins was talking to the P3 performers, though, they didn't have evidence of community transmission. "We would have to cross that bar before we considered doing anything," she says.

The world soon leapt far over that bar. By the time Jenkins and her team decided P3 should be doing something—with their real work beginning in late February--it was too late to prevent this pandemic. But she could help P3 dig into the chemical foundations of COVID-19's malfeasance, and cut off its roots. That work represents, in fact, her roots.

In late February 2020, DARPA received a single blood sample from a recovered COVID-19 patient, in which P3 researchers could go fishing for antibodies. The day it arrived, Jenkins's stomach roiled. "We get one shot," she thought.

Fighting the Smallest Enemies

Jenkins, who's in her early 40s, first got into germs the way many 90s kids did: by reading The Hot Zone, a novel about a hemorrhagic fever gone rogue. It wasn't exactly the disintegrating organs that hooked her. It was the idea that "these very pathogens that we can't even see can make us so sick and bring us to our knees," she says. Reading about scientists facing down deadly disease, she wondered, "How do these things make you so sick?"

She chased that question in college, majoring in both biomolecular science and chemistry, and later became an antibody expert. Antibodies are proteins that hook to a pathogen to block it from attaching to your cells, or tag it for destruction by the rest of the immune system. Soon, she jumped on the "monoclonal antibodies" train—developing synthetic versions of these natural defenses, which doctors can give to people to help them battle an early-stage infection, and even to prevent an infection from taking root after an exposure.

Jenkins likens the antibody treatments to the old aphorism about fishing: Vaccines teach your body how to fish, but antibodies simply give your body the pesca-fare. While that, as the saying goes, won't feed you for a lifetime, it will last a few weeks or months. Monoclonal antibodies thus are a promising preventative option in the immediate short-term when a vaccine hasn't yet been given (or hasn't had time to produce an immune response), as well as an important treatment weapon in the current fight. After former president Donald Trump contracted COVID-19, he received a monoclonal antibody treatment from biotech company Regeneron.

As for Jenkins, she started working as a DARPA Biological Technologies Office contractor soon after completing her postdoc. But it was a suit job, not a labcoat job. And suit jobs, at first, left Jenkins conflicted, worried about being bored. She'd give it a year, she thought. But the year expired, and bored she was not. Around five years later, in June 2019, the agency hired her to manage several of the office's programs. A year into that gig, the world was months into a pandemic.

The Pandemic Pivot

At DARPA, Jenkins inherited five programs, including P3. P3 works by taking blood from recovered people, fishing out their antibodies, identifying the most effective ones, and then figuring out how to manufacture them fast. Back then, P3 existed to help with nebulous, future outbreaks: Pandemic X. Not this pandemic. "I did not have a crystal ball," she says, "but I will say that all of us in the infectious diseases and public-health realm knew that the next pandemic was coming."

Three days after a January 2020 meeting with P3 researchers, COVID-19 appeared in Seattle, then began whipping through communities. The time had come for P3 teams to swivel. "We had done this," she says. "We had practiced this before." But would their methods stand up to something unknown, racing through the global population? "The big anxiety was, 'Wow, this was real,'" says Jenkins.

While facing down that realness, Jenkins was also managing other projects. In one called PREPARE, groups develop "medical countermeasures" that modulate a person's genetic code to boost their bodies' responses to threats. Another project, NOW, envisions shipping-container-sized factories that can make thousands of vaccine doses in days. And then there's Prometheus—which means "forethought" in Greek, and is the name of the god who stole fire and gave it to humans. Wrapping up as COVID ramped up, Prometheus aimed to identify people who are contagious—with whatever—before they start coughing, and even if they never do.

All of DARPA's projects focus on developing early-stage technology, passing it off to other agencies or industry to put it into operation. The orientation toward a specific goal appealed to Jenkins, as a contrast to academia. "You go down a rabbit hole for years at a time sometimes, chasing some concept you found interesting in the lab," she says. That's good for the human pursuit of knowledge, and leads to later applications, but DARPA wants a practical prototype—stat.

"Dual-Use" Technologies

That desire, though, and the fact that DARPA is a defense agency, present philosophical complications. "Bioethics in the national-security context turns all the dials up to 10+," says Jonathan Moreno, a medical ethicist at the University of Pennsylvania.

While developing antibody treatments to stem a pandemic seems straightforwardly good, all biological research—especially that backed by military money—requires evaluating potential knock-on applications, even those that might come from outside the entity that did the developing. As Moreno put it, "Albert Einstein wasn't thinking about blowing up Hiroshima." Particularly sensitive are so-called "dual-use" technologies—those tools that could be used for both benign and nefarious purposes, or are of interest to both the civilian and military worlds.

Moreno takes Prometheus itself as an example of "dual-use" technology. "Think about somebody wearing a suicide vest. Instead of a suicide vest, make them extremely contagious with something. The flu plus Ebola," he says. "Send them someplace, a sensitive environment. We would like to be able to defend against that"—not just tell whether Uncle Fred is bringing asymptomatic COVID home for Christmas. Prometheus, Jenkins says, had safety in mind from the get-go, and required contenders to "develop a risk mitigation plan" and "detail their strategy for appropriate control of information."

To look at a different program, if you can modulate genes to help healing, you probably know something (or know someone else could infer something) about how to hinder healing. Those sorts of risks are why PREPARE researchers got their own "ethical, legal, and social implications" panel, which meets quarterly "to ensure that we are performing all research and publications in a safe and ethical manner," says Jenkins.

DARPA as a whole, Moreno says, is institutionally sensitive to bioethics. The agency has ethics panels, and funded a 2014 National Academies assessment of how to address the "ethical, legal, and societal issues" around technology that has military relevance. "In the cases of biotechnologies where some of that research brushes up against what could legitimately be considered dual-use, that in itself justifies our investment," says Jenkins. "DARPA deliberately focuses on safety and countermeasures against potentially dangerous technologies, and we structure our programs to be transparent, safe, and legal."

Going Fishing

In late February 2020, DARPA received a single blood sample from a recovered COVID-19 patient, in which P3 researchers could go fishing for antibodies. The day it arrived, Jenkins's stomach roiled. "We get one shot," she thought.

As scientists from the P3-funded AbCellera went through the processes they'd practiced, Jenkins managed their work, tracking progress and relaying results. Soon, the team had isolated a suitable protein: bamlanivimab. It attaches to and blocks off the infamous spike proteins on SARS-CoV-2—those sticky suction-cups in illustrations. Partnering with Eli Lilly in a manufacturing agreement, the biotech company brought it to clinical trials in May, just a few months after its work on the deadly pathogen began, after much of the planet became a hot zone.

On November 10—Jenkins's favorite day at the (home) office—the FDA provided Eli Lilly emergency use authorization for bamlanivimab. But she's only mutedly screaming (with joy) inside her heart. "This pandemic isn't 'one morning we're going to wake up and it's all over,'" she says. When it is over, she and her colleagues plan to celebrate their promethean work. "I'm hoping to be able to do it in person," she says. "Until then, I have not taken a breath."