How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

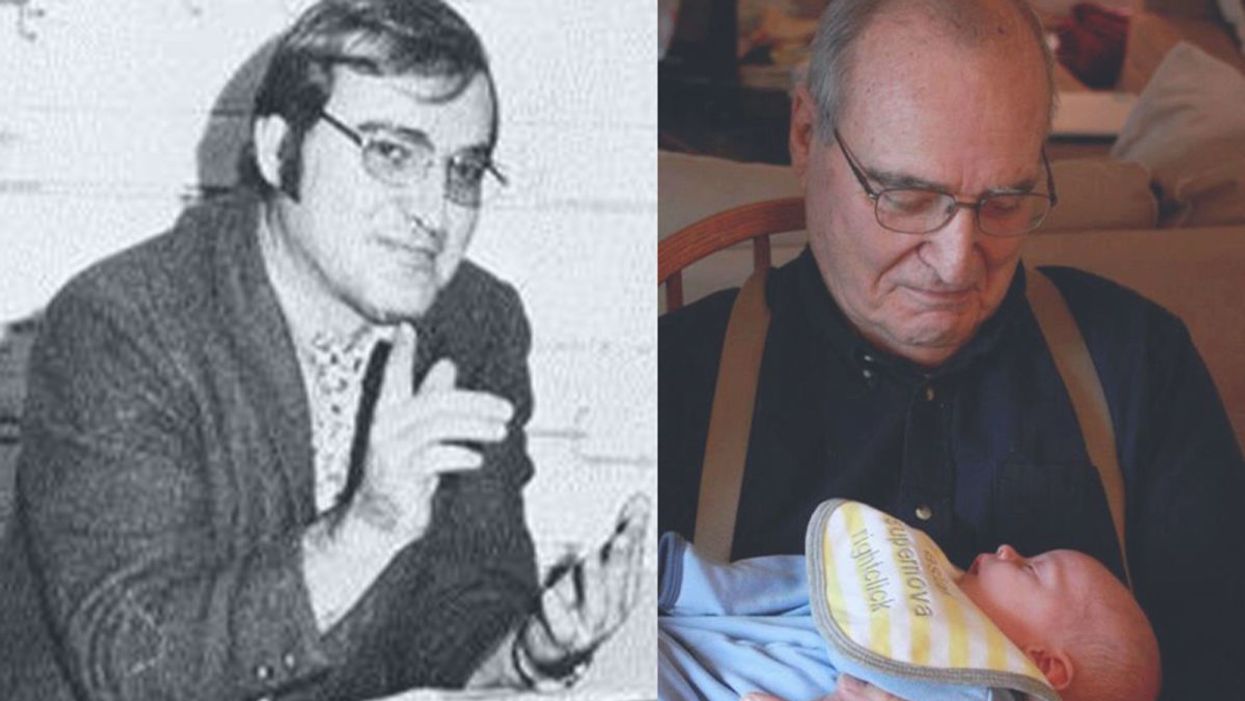

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

How Will the New Strains of COVID-19 Affect Our Vaccination Plans?

The mutated strains that first arose in the U.K. and South Africa and have now spread to many countries are prompting urgent studies on the effectiveness of current vaccines to neutralize the new strains.

When the world's first Covid-19 vaccine received regulatory approval in November, it appeared that the end of the pandemic might be near. As one by one, the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, AstraZeneca, and Sputnik V vaccines reported successful Phase III results, the prospect of life without lockdowns and restrictions seemed a tantalizing possibility.

But for scientists with many years' worth of experience in studying how viruses adapt over time, it remained clear that the fight against the SARS-CoV-2 virus was far from over. "The more virus circulates, the more it is likely that mutations occur," said Professor Beate Kampmann, director of the Vaccine Centre at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. "It is inevitable that new variants will emerge."

Since the start of the pandemic, dozens of new variants of SARS-CoV-2 – containing different mutations in the viral genome sequence - have appeared as it copies itself while spreading through the human population. The majority of these mutations are inconsequential, but in recent months, some mutations have emerged in the receptor binding domain of the virus's spike protein, increasing how tightly it binds to human cells. These mutations appear to make some new strains up to 70 percent more transmissible, though estimates vary and more lab experiments are needed. Such new strains include the B.1.1.7 variant - currently the dominant strain in the UK – and the 501Y.V2 variant, which was first found in South Africa.

"I'm quite optimistic that even with these mutations, immunity is not going to suddenly fail on us."

Because so many more people are becoming infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus as a result, vaccinologists point out that these new strains will prolong the pandemic.

"It may take longer to reach vaccine-induced herd immunity," says Deborah Fuller, professor of microbiology at the University of Washington School of Medicine. "With a more transmissible variant taking over, an even larger percentage of the population will need to get vaccinated before we can shut this pandemic down."

That is, of course, as long as the vaccinations are still highly protective. The South African variant, in particular, contains a mutation called E484K that is raising alarms among scientists. Emerging evidence indicates that this mutation allows the virus to escape from some people's immune responses, and thus could potentially weaken the effectiveness of current vaccines.

What We Know So Far

Over the past few weeks, manufacturers of the approved Covid-19 vaccines have been racing to conduct experiments, assessing whether their jabs still work well against the new variants. This process involves taking blood samples from people who have already been vaccinated and assessing whether the antibodies generated by those people can neutralize the new strains in a test tube.

Pfizer has just released results from the first of these studies, declaring that their vaccine was found to still be effective at neutralizing strains of the virus containing the N501Y mutation of the spike protein, one of the mutations present within both the UK and South African variants.

However, the study did not look at the full set of mutations contained within either of these variants. Earlier this week, academics at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle suggested that the E484K spike protein mutation could be most problematic, publishing a study which showed that the efficacy of neutralizing antibodies against this region dropped by more than ten-fold because of the mutation.

Thankfully, this development is not expected to make vaccines useless. One of the Fred Hutch researchers, Jesse Bloom, told STAT News that he did not expect this mutation to seriously reduce vaccine efficacy, and that more harmful mutations would need to accrue over time to pose a very significant threat to vaccinations.

"I'm quite optimistic that even with these mutations, immunity is not going to suddenly fail on us," Bloom told STAT. "It might be gradually eroded, but it's not going to fail on us, at least in the short term."

While further vaccine efficacy data will emerge in the coming weeks, other vaccinologists are keen to stress this same point: At most, there will be a marginal drop in efficacy against the new variants.

"Each vaccine induces what we call polyclonal antibodies targeting multiple parts of the spike protein," said Fuller. "So if one antibody target mutates, there are other antibody targets on the spike protein that could still neutralize the virus. The vaccine platforms also induce T-cell responses that could provide a second line of defense. If some virus gets past antibodies, T-cell responses can find and eliminate infected cells before the virus does too much damage."

She estimates that if vaccine efficacy decreases, for example from 95% to 85%, against one of the new variants, the main implications will be that some individuals who might otherwise have become severely ill, may still experience mild or moderate symptoms from an infection -- but crucially, they will not end up in intensive care.

"Plug and Play" Vaccine Platforms

One of the advantages of the technologies which have been pioneered to create the Covid-19 vaccines is that they are relatively straightforward to update with a new viral sequence. The mRNA technology used in the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, and the adenovirus vectors used in the Astra Zeneca and Sputnik V vaccines, are known as 'plug and play' platforms, meaning that a new form of the vaccine can be rapidly generated against any emerging variant.

"With a rapid pipeline for manufacture established, these new vaccine technologies could enable production and distribution within 1-3 months of a new variant emerging."

While the technology for the seasonal influenza vaccines is relatively inefficient, requiring scientists to grow and cultivate the new strain in the lab before vaccines can be produced - a process that takes nine months - mRNA and adenovirus-based vaccines can be updated within a matter of weeks. According to BioNTech CEO Uğur Şahin, a new version of their vaccine could be produced in six weeks.

"With a rapid pipeline for manufacture established, these new vaccine technologies could enable production and distribution within 1-3 months of a new variant emerging," says Fuller.

Fuller predicts that more new variants of the virus are almost certain to emerge within the coming months and years, potentially requiring the public to receive booster shots. This means there is one key advantage the mRNA-based vaccines have over the adenovirus technologies. mRNA vaccines only express the spike protein, while the AstraZeneca and Sputnik V vaccines use adenoviruses - common viruses most of us are exposed to - as a delivery mechanism for genes from the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

"For the adenovirus vaccines, our bodies make immune responses against both SARS-CoV-2 and the adenovirus backbone of the vaccine," says Fuller. "That means if you update the adenovirus-based vaccine with the new variant and then try to boost people, they may respond less well to the new vaccine, because they already have antibodies against the adenovirus that could block the vaccine from working. This makes mRNA vaccines more amenable to repeated use."

Regulatory Unknowns

One of the key questions remains whether regulators would require new versions of the vaccine to go through clinical trials, a hurdle which would slow down the response to emerging strains, or whether the seasonal influenza paradigm will be followed, whereby a new form of the vaccine can be released without further clinical testing.

Regulators are currently remaining tight-lipped on which process they will choose to follow, until there is more information on how vaccines respond against the new variants. "Only when such information becomes available can we start the scientific evaluation of what data would be needed to support such a change and assess what regulatory procedure would be required for that," said Rebecca Harding, communications officer for the European Medicines Agency.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did not respond to requests for comment before press time.

While vaccinologists feel it is unlikely that a new complete Phase III trial would be required, some believe that because these are new technologies, regulators may well demand further safety data before approving an updated version of the vaccine.

"I would hope if we ever have to update the current vaccines, regulatory authorities will treat it like influenza," said Drew Weissman, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, who was involved in developing the mRNA technology behind the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines. "I would guess, at worst, they may want a new Phase 1 or 1 and 2 clinical trials."

Others suggest that rather than new trials, some bridging experiments may suffice to demonstrate that the levels of neutralizing antibodies induced by the new form of the vaccine are comparable to the previous one. "Vaccines have previously been licensed by this kind of immunogenicity data only, for example meningitis vaccines," said Kampmann.

While further mutations and strains of SARS-CoV-2 are inevitable, some scientists are concerned that the vaccine rollout strategy being employed in some countries -- of distributing a first shot to as many people as possible, and potentially delaying second shots as a result -- could encourage more new variants to emerge. Just today, the Biden administration announced its intention to release nearly all vaccine doses on hand right away, without keeping a reserve for second shots. This plan risks relying on vaccine manufacturing to ramp up quickly to keep pace if people are to receive their second shots at the right intervals.

"I am not very happy about this change as it could lead to a large number of people out there with partial immunity and this could select new mutations, and escalate the potential problem of vaccine escape."

The Biden administration's shift appears to conflict with the FDA's recent position that second doses should be given on a strict schedule, without any departure from the three- and four-week intervals established in clinical trials. Two top FDA officials said in a statement that changing the dosing schedule "is premature and not rooted solidly in the available evidence. Without appropriate data supporting such changes in vaccine administration, we run a significant risk of placing public health at risk, undermining the historic vaccination efforts to protect the population from COVID-19."

"I understand the argument of trying to get at least partial protection to as many people as possible, but I am concerned about the increased interval between the doses that is now being proposed," said Kampmann. "I am not very happy about this change as it could lead to a large number of people out there with partial immunity and this could select new mutations, and escalate the potential problem of vaccine escape."

But it's worth emphasizing that the virus is unlikely for now to accumulate enough harmful mutations to render the current vaccines completely ineffective.

"It will be very hard for the virus to evolve to completely evade the antibody responses the vaccines induce," said Fuller. "The parts of the virus that are targeted by vaccine-induced antibodies are essential for the virus to infect our cells. If the virus tries to mutate these parts to evade antibodies, then it could compromise its own fitness or even abort its ability to infect. To be sure, the virus is developing these mutations, but we just don't see these variants emerge because they die out."

COVID Vaccines Put Anti-Science Activists to Shame

On a rain-soaked day, thousands marched on Washington, D.C. to fight for science funding and scientific analysis in politics.

It turns out that, despite the destruction and heartbreak caused by the COVID pandemic, there is a silver lining: Scientists from academia, government, and industry worked together and, using the tools of biotechnology, created multiple vaccines that surely will put an end to the worst of the pandemic sometime in 2021. In short, they proved that science works, particularly that which comes from industry. Though politicians and the public love to hate Big Ag and Big Pharma, everybody comes begging for help when the going gets tough.

The change in public attitude is tangible. A headline in the Financial Times declared, "Covid vaccines offer Big Pharma a chance of rehabilitation." In its analysis, the FT says that the pharmaceutical industry is widely reviled because of the high prices it charges for its drugs, among other things, but the speed with which the industry developed COVID vaccines may allow for its reputation to be refurbished.

The Media's Role in Promoting Anti-Biotech Activism

Of course, the media is partly to blame for the pharmaceutical industry's dismal reputation in the first place because of journalists' penchant for oversimplifying complicated stories and pinning blame on an easy scapegoat. While the pharmaceutical industry is far from angelic and places a hefty price tag on its products in the U.S., often gone unmentioned is the fact that high drug prices are the result of multiple factors, including lack of competition (even among generic drugs), foreign price controls that allow citizens of other countries to "free load" off of American consumers, and a deliberately opaque drug supply chain (that involves not only profit-maximizing pharmaceutical manufacturers but "middlemen" like distributors). But why delve into such nuance when it's easier to point to villains like Martin Shkreli?

Big Ag has been subjected to identical mistreatment by the media, with outlets such as the New York Times among the biggest offenders. One article it published compared pesticides to "Nazi-made sarin gas," and another spread misinformation about a high-profile biotech scientist. The website Undark, whose stated mission is "true journalistic coverage of the sciences," once published an opinion piece written by a person who works for an anti-GMO organization and another criticizing Monsanto for its reasonable efforts to defend itself from disinformation. These aren't cherry-picked examples. Overall, the media clearly has taken sides: Science is great, unless it's science from industry.

If the scientific community can use the powerful techniques of biotechnology to cure a previously unknown infectious disease in less than a year, then why shouldn't it be able to cure genetic diseases in humans?

Now, the very same media – which has portrayed the pharmaceutical and biotech industries in the worst possible light, often for political or ideological reasons – is wondering why so many Americans are reluctant to get a COVID vaccine. Perhaps their reportage has something to do with it.

Tech Strikes Back

For years, the agricultural, pharmaceutical, and biotech industries fought back, but to no avail. GMOs are feared, pharma is hated, and biotech is misunderstood. Regulatory red tape abounds. But that may be all about to change, not because of a clever PR campaign, but thanks to the successful coronavirus vaccines produced by the pharma/biotech industry.

All of the major vaccines were created using biotechnology, broadly defined as the use of living systems and organisms to develop products intended to improve human life or the planet. The Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines rely on mRNA (messenger RNA), which is essentially a molecular "photocopy" of the more familiar genetic material DNA. The mRNA molecules were tweaked using biotech and then shown to be 95% effective at preventing COVID in human volunteers. The AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine is based on an older technology that genetically modifies a harmless virus to resemble an immunological target, in this case, SARS-CoV-2. Their vaccine is 62% to 90% effective.

Even better, the pharma/biotech industry showed that it can work hand-in-hand with the government, for instance the FDA, to produce vaccines in record-breaking time. Operation Warp Speed provided some financing to facilitate this process. History will look back at this endeavor and likely conclude that the unprecedented level of cooperation to develop a vaccine in less than 12 months was one of the greatest triumphs in public health history. (The bungled slow rollout is another story.)

Perhaps the most important lesson that society will learn is that the scientific method works.

The pharma/biotech industry has thus gained tremendous momentum. For the first time it seems, those who are opposed to scientific progress and biotechnology are on the defensive. If the scientific community can use the powerful techniques of biotechnology to cure a previously unknown infectious disease in less than a year, then why shouldn't it be able to cure genetic diseases in humans? Or create genetically modified crops that are resistant to insects and drought? Or use genetically modified mosquitoes to help fight against killer diseases like malaria? The arguments against biotechnology have been made exponentially weaker by the success of the coronavirus vaccine.

Perhaps the most important lesson that society will learn is that the scientific method works. We observed (by collecting samples of an unknown virus and sequencing its genome), hypothesized (by predicting which parts of the virus would trigger an immune response), experimented (by recruiting tens of thousands of volunteers into clinical trials), and concluded (that the vaccines worked). It was a thing of pure beauty.

Thanks to all the players involved – from Big Government to Big Pharma – we are beginning the process of being rescued from a modern-day plague. Let us hope that this scientific success also deals a fatal blow to the forces of ignorance that have held back technological progress for decades.

[Editor's Note: LeapsMag is an editorially independent publication that receives program support from Leaps by Bayer. LeapsMag's founding in 2017 predates Bayer's acquisition of Monsanto in 2018. All content published on LeapsMag is strictly free of influence, censorship, and oversight from its corporate sponsor. Read more about LeapsMag's organizational independence here.]