How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

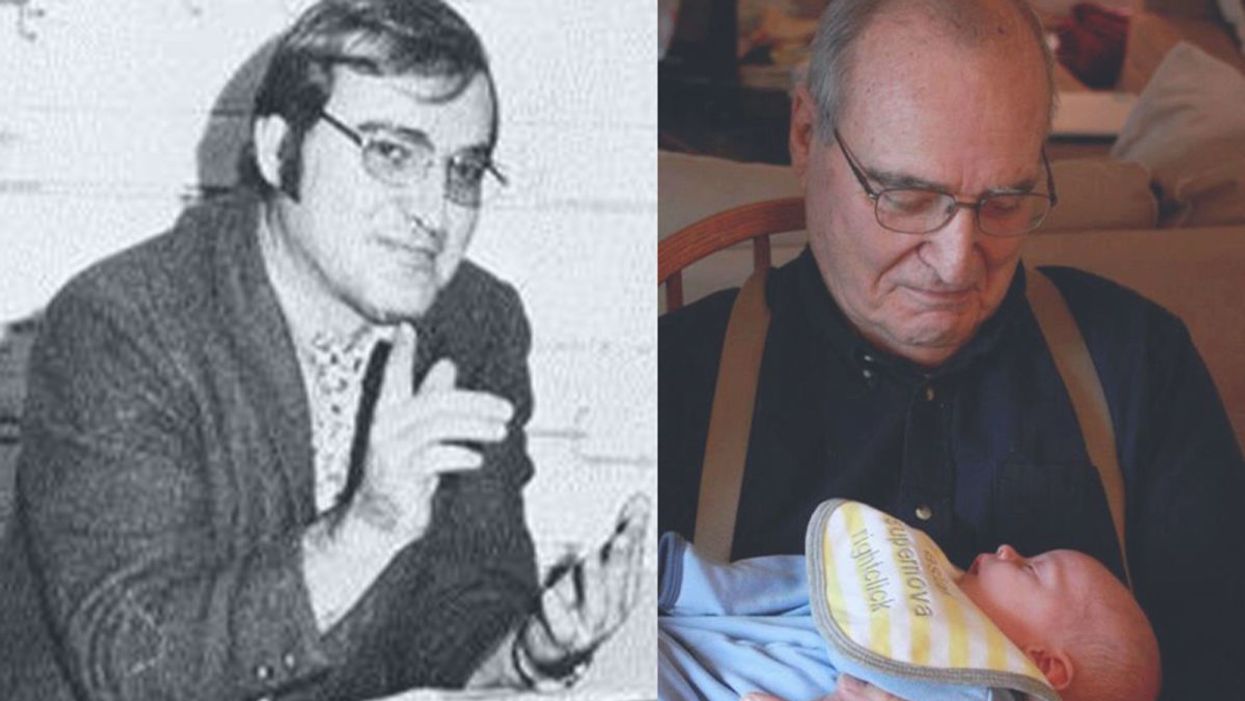

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

A woman gives a DNA sample at a Pheramor-sponsored event.

Brittany Barreto first got the idea to make a DNA-based dating platform nearly 10 years ago when she was in a college seminar on genetics. She joked that it would be called GeneHarmony.com.

Pheramor and startups, like DNA Romance and Instant Chemistry, both based in Canada, claim to match you to a romantic partner based on your genetics.

The idea stuck with her while she was getting her PhD in genetics at Baylor College of Medicine, and in March 2018, she launched Pheramor, a dating app that measures compatibility based on physical chemistry and what the company calls "social alignment."

"I wanted to use genetics and science to help people connect more. Our world is so hungry for connection," says Barreto, who serves as Pheramor's CEO.

With the direct-to-consumer genetic testing market booming, more and more companies are looking to capitalize on the promise of DNA-based services. Pheramor and startups, like DNA Romance and Instant Chemistry, both based in Canada, claim to match you to a romantic partner based on your genetics. It's an intriguing alternative to swiping left or right in hopes of finding someone you're not only physically attracted to but actually want to date. Experts say the science behind such apps isn't settled though.

For $40, Pheramor sends you a DNA kit to swab the inside of your cheek. After you mail in your sample, Pheramor analyzes your saliva for 11 different HLA genes, a fraction of the more than 200 genes that are thought to make up the human HLA complex. These genes make proteins that regulate the immune system by helping protect against invading pathogens.

It takes three to four weeks to get the results backs. In the meantime, users can still download the app and start using it before their DNA results are ready. The app asks users to link their social media accounts, which are fed into an algorithm that calculates a "social alignment." The algorithm takes into account the hashtags you use, your likes, check-ins, posts, and accounts you follow on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

The DNA test results and social alignment algorithm are used to calculate a compatibility percentage between zero and 100. Barreto said she couldn't comment on how much of that score is influenced by the algorithm and how much comes from what the company calls genetic attraction. "DNA is not destiny," she says. "It's not like you're going to swab and I'll send you your soulmate."

Despite its name, Pheramor doesn't actually measure pheromones, chemicals released by animals that affect the behavior of others of the same species. That's because human pheromones have yet to be identified, though they've been discovered throughout the animal kingdom in moths, mice, rabbits, pigs, and many other insects and mammals. The HLA genes Pheramor analyzes instead are the human version of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), a gene group found in many species.

The connection between HLA type and attraction goes back to the 1970s, when researchers found that inbred male mice preferred to mate with female mice with a different MHC rather than inbred female mice with similar immune system genes. The researchers concluded that this mating preference was linked to smell. The idea is that choosing a mate with different MHC genes gives animals an evolutionary advantage in terms of immune system defense.

The couples who had more dissimilar HLA types reported a more satisfied sex life and satisfied partnership, but it was a small effect.

In the 1990s, Swiss scientists wanted to see if body odor also had an effect on human attraction. In a famous experiment known as the "sweaty T-shirt study", they recruited 49 women to sniff sweaty, unwashed T-shirts from 44 men and put each in a box with a smelling hole and describe the odors of every shirt. The study found that women preferred the scents of T-shirts worn by men who were immunologically different from them compared to men whose HLA genes were similar to their own.

"The idea is, if you are very similar with your partner in HLA type then your offspring is similar in terms of HLA. This reduces your resistance against pathogens," says Illona Croy, a psychologist at the Technical University of Dresden who has studied HLA type in relation to sexual attraction in humans.

In a 2016 study Pheramor cites on its website, Croy and her colleagues tested the HLA types of 250 couples—all of them university students—and asked them how satisfied they were with their partnerships, with their sex lives, and with the odors of their partners. The couples who had more dissimilar HLA types reported a more satisfied sex life and satisfied partnership, but Croy cautions that it was a small effect. "It's not like they were super satisfied or not satisfied at all. It's a slight difference," she says.

Croy says we're much more likely to choose a partner based on appearance, sense of humor, intelligence and common interests.

Other studies have reported no preference for HLA difference in sexual attraction. Tristram Wyatt, a zoologist at the University of Oxford in the U.K. who studies animal pheromones, says it's been difficult to replicate the original T-shirt study. And one of the caveats of the original study is that women who were taking birth control pills preferred men who were more immunologically similar.

"Certainly, we learn to really like the smell of our partners," Wyatt says. "Whether it's the reason for choosing them in the first place, we really don't know."

Wyatt says he's skeptical of DNA-based dating apps because there are many subtypes of HLA genes, meaning there's a fairly low chance that your HLA type and your romantic partner's would be an exact match, anyway. It's why finding a suitable match for a bone marrow transplant is difficult; a donor's HLA type has to be the same as the recipient's.

"What it means is that since we're all different, it's hard statistically to say who the best match will be," he says.

DNA-based dating apps haven't yet gone mainstream, but some people seem willing to give them a try. Since Pheramor's launch a little over a year ago, about 10,000 people have signed up to use the app, about half of which have taken the DNA test, Barreto says. By comparison, an estimated 50 million people use Tinder, which has been around since 2012, and about 40 million people are on Bumble, which was released in 2014.

In April, Barreto launched a second service, this one for couples, called WeHaveChemistry.com. A $139 kit includes two genetic tests, one for you and your partner, and a detailed DNA report on your sexual compatibility.

Unlike the Phermor app, WeHaveChemistry doesn't provide users with a numeric combability score but instead makes personalized recommendations based on your genetic results. For instance, if the DNA test shows that your HLA genes are similar, Barreto says, "We might recommend pheromone colognes, working out together, or not showering before bed to get your juices running."

Despite her own research on HLA and sexual compatibility, Croy isn't sure how knowing HLA type will help couples. However, some researchers are doing studies on whether HLA types are related to certain cases of infertility, and this is where a genetic test might be very useful, says Croy.

"Otherwise, I think it doesn't matter whether we're HLA compatible or not," she says. "It might give you one possible explanation about why your sexual life isn't as satisfactory as it could be, but there are many other factors that play a role."

On left, the fungus (the whitish, fluffy material) of the Fungi Mutarium growing within the agar cups and degrading the plastic (the black/gray material in the center).

Between the ever-growing Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the news that over 90% of plastic isn't recycled, and the likely state of your personal trash can, it's clear that the world has a plastic problem.

Scientists around the world have continued to discover different types of fungus that can degrade specific types of plastic.

We now have 150 million tons of plastic in our oceans, according to estimates; by 2050, there could be more plastic than fish. And every new batch of trash compounds the issue: Plastic is notorious for its longevity and resistance to natural degradation.

The Lowdown

Enter the humble mushroom. In 2011, Yale students made headlines with the discovery of a fungus in Ecuador, Pestalotiopsis microspora, that has the ability to digest and break down polyurethane plastic, even in an air-free (anaerobic) environment—which might even make it effective at the bottom of landfills. Although the professor who led the research trip cautioned for moderate expectations, there's an undeniable appeal to the idea of a speedier, cleaner, side effect-free, and natural method of disposing of plastic.

A few years later, this particular application for fungus got a jolt of publicity from designer Katharina Unger, of LIVIN Studio, when she collaborated with the microbiology faculty at Utrecht University to create a project called the Fungi Mutarium. They used the mycelium—which is the threadlike, vegetative part of a mushroom—of two very common types of edible mushrooms, Pleurotus ostreatus (Oyster mushrooms) and Schizophyllum commune (Split gill mushrooms). Over the course of a few months, the fungi fully degraded small pieces of plastic while growing around pods of edible agar. The result? In place of plastic, a small mycelium snack.

Other researchers have continued to tackle the subject. In 2017, scientist Sehroon Khan and his research team at the World Agroforestry Centre in Kunming, China discovered another biodegrading fungus in a landfill in Islamabad, Pakistan: Aspergillus tubingensis, which turns out to be capable of colonizing polyester polyurethane (PU) and breaking it down it into smaller pieces within the span of two months. (PU often shows up in the form of packing foam—the kind of thing you might find cushioning a microwave or a new TV.)

Next Up

Utrecht University has continued its research, and scientists around the world have continued to discover different types of fungus that can degrade different, specific types of plastic. Khan and his team alone have discovered around 50 more species since 2017. They are currently working on finding the optimal conditions of temperature and environment for each strain of fungus to do its work.

Their biggest problem is perhaps the most common obstacle in innovative scientific research: Cash. "We are developing these things for large-scale," Khan says. "But [it] needs a lot of funding to get to the real application of plastic waste." They plan to apply for a patent soon and to publish three new articles about their most recent research, which might help boost interest and secure more grants.

Is there a way to get the fungi to work faster and to process bigger batches?

Khan's team is working on the breakdown process at this point, but researchers who want to continue in Unger's model of an edible end product also need to figure out how to efficiently and properly prepare the plastic input. "The fungi is sensitive to infection from bacteria," Unger says—which could turn it into a destructive mold. "This is a challenge for industrialization—[the] sterilization of the materials, and making the fungi resistant, strong, and faster-growing, to allow for a commercial process."

Open Questions

Whether it's Khan's polyurethane-chomping fungus or the edible agar pods from the Fungi Mutarium, the biggest question is still about scale. Both projects took several months to fully degrade a small amount of plastic. That's much shorter than plastic's normal lifespan, but still won't be enough to keep up with the global production of plastic. Is there a way to get the fungi to work faster and to process bigger batches?

We'd also need to figure out where these plastic recyclers would live. Could individuals keep a small compost-like heap, feeding in their own plastic and harvesting the mushrooms? Or could this be a replacement for local recycling centers?

There are still only these few small experiments for reference. But taken together, they suggest a fascinating future for waste disposal: An army of mycelium chewing quietly and methodically through our plastic bags and foam coffee cups—and potentially even creating a new food source along the way. We could have our trash and eat it, too.