How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

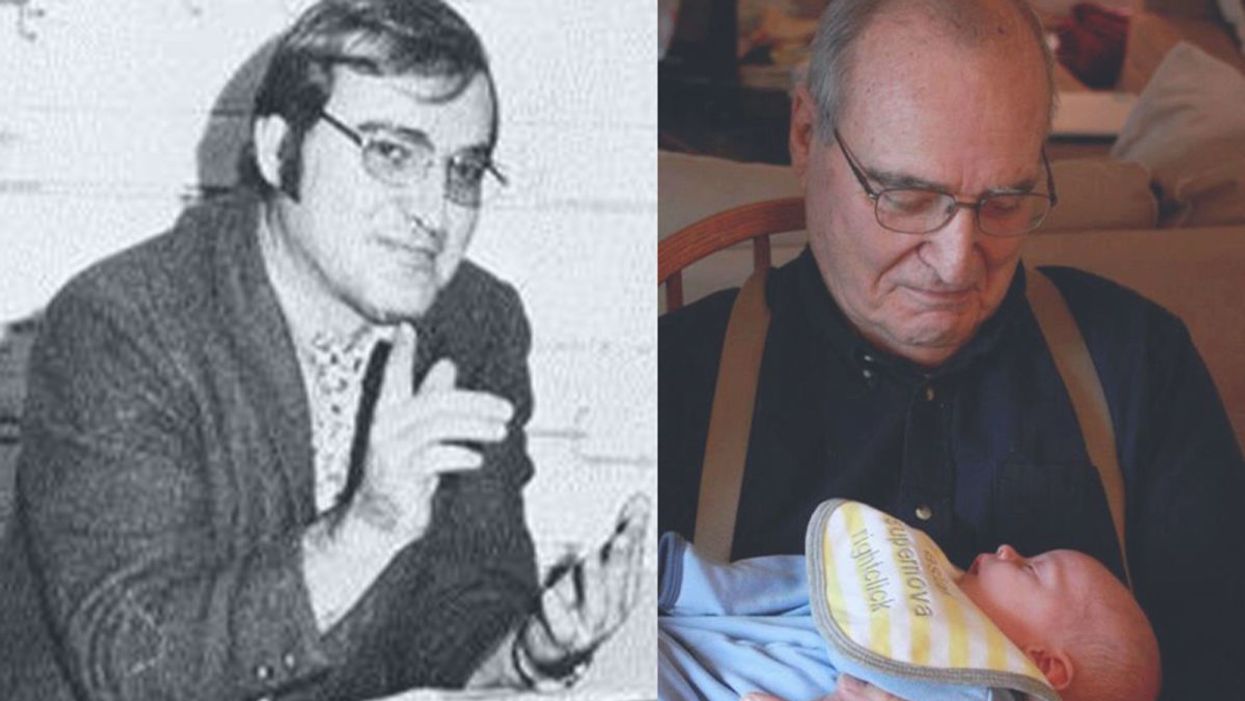

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

Chris Mirabile sprints on a track in Sarasota, Florida, during his daily morning workout. He claims to be a superager already, at age 38, with test results to back it up.

Earlier this year, Harvard scientists reported that they used an anti-aging therapy to reverse blindness in elderly mice. Several other studies in the past decade have suggested that the aging process can be modified, at least in lab organisms. Considering mice and humans share virtually the same genetic makeup, what does the rodent-based study mean for the humans?

In truth, we don’t know. Maybe nothing.

What we do know, however, is that a growing number of people are dedicating themselves to defying the aging process, to turning back the clock – the biological clock, that is. Take Bryan Johnson, a man who is less mouse than human guinea pig. A very wealthy guinea pig.

The 45-year-old venture capitalist spends over $2 million per year reversing his biological clock. To do this, he employs a team of 30 medical doctors and other scientists. His goal is to eventually reset his biological clock to age 18, and “have all of his major organs — including his brain, liver, kidneys, teeth, skin, hair, penis and rectum — functioning as they were in his late teens,” according to a story earlier this year in the New York Post.

But his daily routine paints a picture that is far from appealing: for example, rigorously adhering to a sleep schedule of 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. and consuming more than 100 pills and precisely 1,977 calories daily. Considering all of Johnson’s sacrifices, one discovers a paradox:

To live forever, he must die a little every day until he reaches his goal - if he ever reaches his goal.

Less extreme examples seem more helpful for people interested in happy, healthy aging. Enter Chris Mirabile, a New Yorker who says on his website, SlowMyAge.com, that he successfully reversed his biological age by 13.6 years, from the chronological age of 37.2 to a biological age of 23.6. To put this achievement in perspective, Johnson, to date, has reversed his biological clock by 2.5 years.

Mirabile's habits and overall quest to turn back the clock trace back to a harrowing experience at age 16 during a school trip to Manhattan, when he woke up on the floor with his shirt soaked in blood.

Mirabile, who is now 38, supports his claim with blood tests that purport to measure biological age by assessing changes to a person’s epigenome, or the chemical marks that affect how genes are expressed. Mirabile’s tests have been run and verified independently by the same scientific lab that analyzes Johnson’s. (In an email to Leaps.org, the lab, TruDiagnostic, confirmed Mirabile’s claims about his test results.)

There is considerable uncertainty among scientists about the extent to which these tests can accurately measure biological age in individuals. Even so, Mirabile’s results are intriguing. They could reflect his smart lifestyle for healthy aging.

His habits and overall quest to turn back the clock trace back to a harrowing experience at age 16 during a school trip to Manhattan, when Mirabile woke up on the floor with his shirt soaked in blood. He’d severed his tongue after a seizure. He later learned it was caused by a tumor the size of a golf ball. As a result, “I found myself contemplating my life, what I had yet to experience, and mortality – a theme that stuck with me during my year of recovery and beyond,” Mirabile told me.

For the next 15 years, he researched health and biology, integrating his learnings into his lifestyle. Then, in his early 30s, he came across an article in the journal Cell, "The Hallmarks of Aging," that outlined nine mechanisms of the body that define the aging process. Although the paper says there are no known interventions to delay some of these mechanisms, others, such as inflammation, struck Mirabile as actionable. Reading the paper was his “moment of epiphany” when it came to the areas where he could assert control to maximize his longevity.

He also wanted “to create a resource that my family, friends, and community could benefit from in the short term,” he said. He turned this knowledge base into a company called NOVOS dedicated to extending lifespan.

His longevity advice is more accessible than Johnson’s multi-million dollar approach, as Mirabile spends a fraction of that amount. Mirabile takes one epigenetic test per year and has a gym membership at $45 per month. Unlike Johnson, who takes 100 pills per day, Mirabile takes 10, costing another $45 monthly, including a B-complex, fish oil, Vitamins D3 and K2, and two different multivitamin supplements.

Mirabile’s methods may be easier to apply in other ways as well, since they include activities that many people enjoy anyway. He’s passionate about outdoor activities, travels frequently, and has loving relationships with friends and family, including his girlfriend and collie.

Here are a few of daily routines that could, he thinks, contribute to his impressively young bio age:

After waking at 7:45 am, he immediately drinks 16 ounces of water, with 1/4 teaspoon of sodium and potassium to replenish electrolytes. He takes his morning vitamins, brushes and flosses his teeth, puts on a facial moisturizing sunblock and goes for a brisk, two-mile walk in the sun. At 8:30 am on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays he lift weights, focusing on strength and power, especially in large muscle groups.

Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays are intense cardio days. He runs 5-7 miles or bicycles for 60 minutes first thing in the morning at a brisk pace, listening to podcasts. Sunday morning cardio is more leisurely.

After working out each day, he’s back home at 9:20 am, where he makes black coffee, showers, then applies serum and moisturizing sunblock to his face. He works for about three hours on his laptop, then has a protein shake and fruit.

Mirabile is a dedicated intermittent faster, with a six hour eating window in between 18 hours fasts. At 3 pm, he has lunch. The Mediterranean lineup often features salmon, sardines, olive oil, pink Himalayan salt plus potassium salt for balance, and lots of dried herbs and spices. He almost always finishes with 1/3 to 1/2 bar of dark chocolate.

If you are what you eat, Mirabile is made of mostly plants and lean meats. He follows a Mediterranean diet full of vegetables, fruits, fatty fish and other meats full of protein and unsaturated fats. “These may cost more than a meal at an American fast-food joint, but then again, not by much,” he said. Each day, he spends $25 on all his meals combined.

At 6 pm, he takes the dog out for a two-mile walk, taking calls for work or from family members along the way. At 7 pm, he dines with his girlfriend. Like lunch, this meal is heavy on widely available ingredients, including fish, fresh garlic, and fermented food like kimchi. Mirabile finishes this meal with sweets, like coconut milk yogurt with cinnamon and clove, some stevia, a mix of fresh berries and cacao nibs.

If Mirabile's epigenetic tests are accurate, his young biological age could be thanks to his healthy lifestyle, or it could come from a stroke of luck if he inherited genes that protect against aging.

At 8 pm, he wraps up work duties and watches shows with his girlfriend, applies serum and moisturizer yet again, and then meditates with the lights off. This wind-down, he said, improves his sleep quality. Wearing a sleep mask and earplugs, he’s asleep by about 10:30.

“I’ve achieved stellar health outcomes, even after having had the physiological stressors of a brain tumor, without spending a fortune,” Mirabile said. “In fact, even during times when I wasn’t making much money as a startup founder with few savings, I still managed to live a very healthy, pro-longevity lifestyle on a modest budget.”

Mirabile said living a cleaner, healthier existence is a reality that many readers can achieve. It’s certainly true that many people live in food deserts and have limited time for exercise or no access to gyms, but James R. Doty, a clinical professor of neurosurgery at Stanford, thinks many can take more action to stack the odds that they’ll “be happy and live longer.” Many of his recommendations echo aspects of Mirabile’s lifestyle.

Each night, Doty said, it’s vital to get anywhere between 6-8 hours of good quality sleep. Those who sleep less than 6 hours per night are at an increased risk of developing a whole host of medical problems, including high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and stroke.

In addition, it’s critical to follow Mirabile’s prescription of exercise for about one hour each day, and intensity levels matter. Doty noted that, in 2017, researchers at Brigham Young University found that people who ran at a fast pace for 30-40 minutes five days per week were, on average, biologically younger by nine years, compared to those who subscribed to more moderate exercise programs, as well as those who rarely exercised.

When it comes to nutrition, one should consider fasting for 16 hours per day, Doty said. This is known as the 16/8 method, where one’s daily calories are consumed within an eight hour window, fasting for the remaining 16 hours, just like Mirabile. Intermittent fasting is associated with cellular repair and less inflammation, though it’s not for everyone, Doty added. Consult with a medical professional before trying a fasting regimen.

Finally, Doty advised to “avoid anger, avoid stress.” Easier said than done, but not impossible. “Between stimulus and response, there is a pause and within that pause lies your freedom,” Doty said. Mirabile’s daily meditation ritual could be key to lower stress for healthy aging. Research has linked regular, long-term meditation to having a lower epigenetic age, compared to control groups.

Many other factors could apply. Having a life purpose, as Mirabile does with his company, has also been associated with healthy aging and lower epigenetic age. Of course, Mirabile is just one person, so it’s hard to know how his experience will apply to others. If his tests are accurate, his young biological age could be thanks to his healthy lifestyle, or it could come from a stroke of luck if he inherited genes that protect against aging. Clearly, though, any such genes did not protect him from cancer at an early age.

The third and perhaps most likely explanation: Mirabile’s very young biological age results from a combination of these factors. Some research shows that genetics account for only 25 percent of longevity. That means environmental factors could be driving the other 75 percent, such as where you live, frequency of exercise, quality of nutrition and social support.

The middle-aged – even Brian Johnson – probably can’t ever be 18 again. But more modest goals are reasonable for many. Control what you can for a longer, healthier life.

FDA, researchers work to make clinical trials more diverse

The U.S. population is becoming more diverse, but clinical trials don't reflect that, experts say. Some are focusing on recruiting minorities to participate in research.

Nestled in a predominately Hispanic neighborhood, a new mural outside Guadalupe Centers Middle School in Kansas City, Missouri imparts a powerful message: “Clinical Research Needs Representation.” The colorful portraits painted above those words feature four cancer survivors of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Two individuals identify as Hispanic, one as African American and another as Native American.

One of the patients depicted in the mural is Kim Jones, a 51-year-old African American breast cancer survivor since 2012. She advocated for an African American friend who participated in several clinical trials for ovarian cancer. Her friend was diagnosed in an advanced stage at age 26 but lived nine more years, thanks to the trials testing new therapeutics. “They are definitely giving people a longer, extended life and a better quality of life,” said Jones, who owns a nail salon. And that’s the message the mural aims to send to the community: Clinical trials need diverse participants.

While racial and ethnic minority groups represent almost half of the U.S. population, the lack of diversity in clinical trials poses serious challenges. Limited awareness and access impede equitable representation, which is necessary to prove the safety and effectiveness of medical interventions across different groups.

A Yale University study on clinical trial diversity published last year in BMJ Medicine found that while 81 percent of trials testing the new cancer drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration between 2012 and 2017 included women, only 23 percent included older adults and 5 percent fairly included racial and ethnic minorities. “It’s both a public health and social justice issue,” said Jennifer E. Miller, an associate professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine. “We need to know how medicines and vaccines work for all clinically distinct groups, not just healthy young White males.” A recent JAMA Oncology editorial stresses out the need for legislation that would require diversity action plans for certain types of trials.

Ensuring meaningful representation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials for regulated medical products is fundamental to public health.--FDA Commissioner Robert M. Califf.

But change is on the horizon. Last April, the FDA issued a new draft guidance encouraging industry to find ways to revamp recruitment into clinical trials. The announcement, which expanded on previous efforts, called for including more participants from underrepresented racial and ethnic segments of the population.

“The U.S. population has become increasingly diverse, and ensuring meaningful representation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials for regulated medical products is fundamental to public health,” FDA commissioner Robert M. Califf, a physician, said in a statement. “Going forward, achieving greater diversity will be a key focus throughout the FDA to facilitate the development of better treatments and better ways to fight diseases that often disproportionately impact diverse communities. This guidance also further demonstrates how we support the Administration’s Cancer Moonshot goal of addressing inequities in cancer care, helping to ensure that every community in America has access to cutting-edge cancer diagnostics, therapeutics and clinical trials.”

Lola Fashoyin-Aje, associate director for Science and Policy to Address Disparities in the Oncology Center of Excellence at the FDA, said that the agency “has long held the view that clinical trial participants should reflect the clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients who will ultimately receive the drug once approved.” However, “numerous studies over many decades” have measured the extent of underrepresentation. One FDA analysis found that the proportion of White patients enrolled in U.S. clinical trials (88 percent) is much higher than their numbers in country's population. Meanwhile, the enrollment of African American and Native Hawaiian/American Indian and Alaskan Native patients is below their national numbers.

The FDA’s guidance is accelerating researchers’ efforts to be more inclusive of diverse groups in clinical trials, said Joyce Sackey, a clinical professor of medicine and associate dean at Stanford School of Medicine. Underrepresentation is “a huge issue,” she noted. Sackey is focusing on this in her role as the inaugural chief equity, diversity and inclusion officer at Stanford Medicine, which encompasses the medical school and two hospitals.

Until the early 1990s, Sackey pointed out, clinical trials were based on research that mainly included men, as investigators were concerned that women could become pregnant, which would affect the results. This has led to some unfortunate consequences, such as indications and dosages for drugs that cause more side effects in women due to biological differences. “We’ve made some progress in including women, but we have a long way to go in including people of different ethnic and racial groups,” she said.

A new mural outside Guadalupe Centers Middle School in Kansas City, Missouri, advocates for increasing diversity in clinical trials. Kim Jones, 51-year-old African American breast cancer survivor, is second on the left.

Artwork by Vania Soto. Photo by Megan Peters.

Among racial and ethnic minorities, distrust of clinical trials is deeply rooted in a history of medical racism. A prime example is the Tuskegee Study, a syphilis research experiment that started in 1932 and spanned 40 years, involving hundreds of Black men with low incomes without their informed consent. They were lured with inducements of free meals, health care and burial stipends to participate in the study undertaken by the U.S. Public Health Service and the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

By 1947, scientists had figured out that they could provide penicillin to help patients with syphilis, but leaders of the Tuskegee research failed to offer penicillin to their participants throughout the rest of the study, which lasted until 1972.

Opeyemi Olabisi, an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, aims to increase the participation of African Americans in clinical research. As a nephrologist and researcher, he is the principal investigator of a clinical trial focusing on the high rate of kidney disease fueled by two genetic variants of the apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) gene in people of recent African ancestry. Individuals of this background are four times more likely to develop kidney failure than European Americans, with these two variants accounting for much of the excess risk, Olabisi noted.

The trial is part of an initiative, CARE and JUSTICE for APOL1-Mediated Kidney Disease, through which Olabisi hopes to diversify study participants. “We seek ways to engage African Americans by meeting folks in the community, providing accessible information and addressing structural hindrances that prevent them from participating in clinical trials,” Olabisi said. The researchers go to churches and community organizations to enroll people who do not visit academic medical centers, which typically lead clinical trials. Since last fall, the initiative has screened more than 250 African Americans in North Carolina for the genetic variants, he said.

Other key efforts are underway. “Breaking down barriers, including addressing access, awareness, discrimination and racism, and workforce diversity, are pivotal to increasing clinical trial participation in racial and ethnic minority groups,” said Joshua J. Joseph, assistant professor of medicine at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Along with the university’s colleges of medicine and nursing, researchers at the medical center partnered with the African American Male Wellness Agency, Genentech and Pfizer to host webinars soliciting solutions from almost 450 community members, civic representatives, health care providers, government organizations and biotechnology professionals in 25 states and five countries.

Their findings, published in February in the journal PLOS One, suggested that including incentives or compensation as part of the research budget at the institutional level may help resolve some issues that hinder racial and ethnic minorities from participating in clinical trials. Compared to other groups, more Blacks and Hispanics have jobs in service, production and transportation, the authors note. It can be difficult to get paid leave in these sectors, so employees often can’t join clinical trials during regular business hours. If more leaders of trials offer money for participating, that could make a difference.

Obstacles include geographic access, language and other communications issues, limited awareness of research options, cost and lack of trust.

Christopher Corsico, senior vice president of development at GSK, formerly GlaxoSmithKline, said the pharmaceutical company conducted a 17-year retrospective study on U.S. clinical trial diversity. “We are using epidemiology and patients most impacted by a particular disease as the foundation for all our enrollment guidance, including study diversity plans,” Corsico said. “We are also sharing our results and ideas across the pharmaceutical industry.”

Judy Sewards, vice president and head of clinical trial experience at Pfizer’s headquarters in New York, said the company has committed to achieving racially and ethnically diverse participation at or above U.S. census or disease prevalence levels (as appropriate) in all trials. “Today, barriers to clinical trial participation persist,” Sewards said. She noted that these obstacles include geographic access, language and other communications issues, limited awareness of research options, cost and lack of trust. “Addressing these challenges takes a village. All stakeholders must come together and work collaboratively to increase diversity in clinical trials.”

It takes a village indeed. Hope Krebill, executive director of the Masonic Cancer Alliance, the outreach network of the University of Kansas Cancer Center in Kansas City, which commissioned the mural, understood that well. So her team actively worked with their metaphorical “village.” “We partnered with the community to understand their concerns, knowledge and attitudes toward clinical trials and research,” said Krebill. “With that information, we created a clinical trials video and a social media campaign, and finally, the mural to encourage people to consider clinical trials as an option for care.”

Besides its encouraging imagery, the mural will also be informational. It will include a QR code that viewers can scan to find relevant clinical trials in their location, said Vania Soto, a Mexican artist who completed the rendition in late February. “I’m so honored to paint people that are survivors and are living proof that clinical trials worked for them,” she said.

Jones, the cancer survivor depicted in the mural, hopes the image will prompt people to feel more open to partaking in clinical trials. “Hopefully, it will encourage people to inquire about what they can do — how they can participate,” she said.