How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

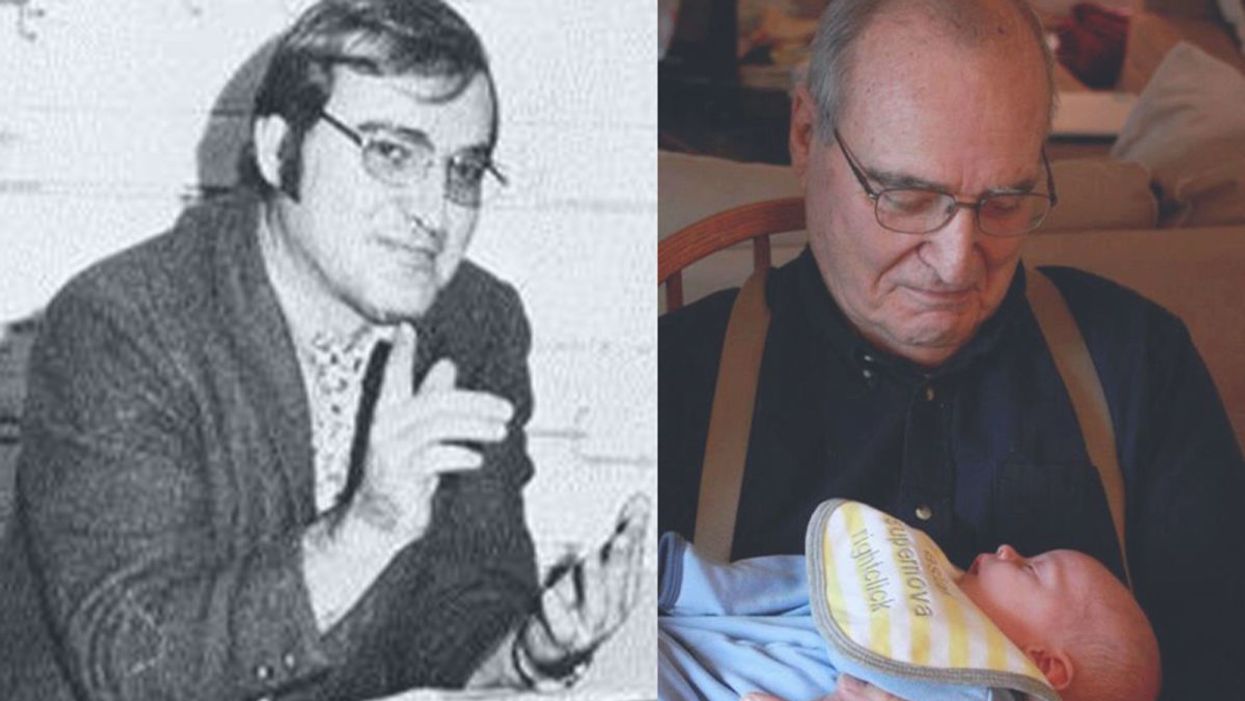

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

These doctors have a heart for recycling

In the U.S. and Europe, it is illegal to reuse pacemakers and other implants. Therefore, cardiologists export them to the global South where they save the lives of people of all ages.

This is part 3 of a three part series on a new generation of doctors leading the charge to make the health care industry more sustainable - for the benefit of their patients and the planet. Read part 1 here and part 2 here.

One could say that over 400 people owe their life to the fact that Carsten Israel fell in love. Twenty years ago, as a young doctor in Frankfurt, Germany, he began to court an au pair from Kenya, Elisabeth, his now-wife of 13 years with whom he has three children. When the couple started visiting her parents in Kenya, Israel wanted to check out the local hospitals, “just out of professional curiosity,“ says the cardiologist, who is currently the head doctor at the Clinic for Interior Medicine in Bielefeld. “I was completely shocked.“

Often he observed there were no doctors in the E.R.s, and hte nurses could render only basic first aid. “When somebody fell into a coma, they fell into a coma,“ Israel remembers. “There weren’t even any defibrillators to restart a patient’s heart,” while defibrillators are standard equipment in most clinics in the U.S. and Europe as lifesaving devices. When Israel finally visited the largest and most modern hospital in Nairobi, he found it better equipped but he learned that its services were only available to patients who could afford them. The cardiologist there had a drawer full of petitions from patients with heart ailments who couldn’t afford lifesaving surgery. Even two decades ago, a pacemaker cost $5,000 in Kenya, which made it unaffordable for most Kenyans who earn an average of $600 per month.

Since 2003, Israel and a team of two doctors and two nurses visit Kenya and Zambia once or twice a year to implant German pacemakers for free. Notably, the pacemakers and defibrillators Israel exports to Africa would end up in the landfill in Germany. Clinics have to pay for specialized services to dispose of this medical equipment. “In Germany, I could go to jail if I used a defibrillator that is one day past its expiration date,“ Israel says, “but in Kenya, people don’t have the money for the cheapest model. What nonsense to throw this precious medical equipment away while people in poorer countries die because they desperately need it.“

Israel works at the breakpoint between the laws in a wealthy country like Germany and the reality in the global South. The U.S. and most European countries have strict laws that ban the reuse of medical implants and enforce strict expiration dates for medical equipment. “But if a pacemaker is a few days past its expiration date, it still works perfectly fine,“ Israel says. “And it also happens that we implant a pacemaker and five months later it turns out that the patient needs a different kind. Then we replace it and we’d have to trash the first one in Germany, though it could easily run another 12 years.“

“If we get this right, we have lots of devices we can implant, hips and knees, etcetera. Where this will lead is limitless," says Eva Kline Rogers, the program coordinator for My Heart, Your Heart.

Israel has been collecting donations of pacemakers and defibrillators from manufacturers but also from other doctors and from funeral homes for his nonprofit Pacemakers for East Africa since 2003. Most funeral homes in the U.S. and Europe are legally obliged to remove pacemakers from the dead before cremation. “Most pacemakers survive their owners,“ says Israel. He sterilizes the pacemakers and finds them a new life in East Africa. Studies show that reused pacemakers carry no greater risk for the patients than new ones.

In the U.S., University of Michigan professor Thomas Crawford heads up a similar initiative, My Heart, Your Heart. “Each year 1 to 2 million individuals worldwide die due to a lack of access to pacemakers and defibrillators,” the organization notes on its website. The nonprofit was founded in 2009, but it took four years for the doctors to get permission from the FDA to export pacemakers. Since receiving permission, the organization has sent dozens of devices to the Philippines, Haiti, Venezuela, Kenya, Sierra Leone and Ukraine. “We were the first doctors ever to implant a pacemaker in Sierra Leone in 2018,” says Crawford, who has traveled extensively to most of the recipient countries.

Even individuals can donate their pacemakers; the organization offers a prepaid envelope. “My mother recently passed and she donated her device,” says Tina Alexandris-Souphis, one of the doctors at University of Michigan who collaborates on My Heart, Your Heart. The organization works with World Medical Relief and the U.K. based charity Pace4Life to maintain a registry of the most urgent patients and send devices to where they are needed the most.

My Heart, Your Heart is also conducting a randomized controlled trial to provide further evidence that reused pacemakers pose no additional risk. “Our vision is that we establish this is safe and create a blueprint for organizations around the world to safely reuse these devices instead of them being thrown in the trash,” says Eva Kline Rogers, the program’s coordinator. “If we get this right, we have lots of devices we can implant, hips and knees, etc. Where this will lead is limitless.” She points out that in addition to receiving the donated devices, the doctors in the global South also benefit from the expertise of renowned cardiologists, such as Crawford, who sometimes advise them in complex cases.

And Adrian Baranchuk, a Canadian doctor at the Kingston General Hospital at the Queen’s University, regularly travels through South America with his “cardiology van” to help villagers in remote areas with heart problems.

Israel says that he’s been accused of racism, in thinking that these pacemakers are suitable for those in the global South - many of whom are people of color - even though officials in wealthier countries consider them to be trash. The cardiologist counters such criticism with stories about desperate need of his patients. At his first medical visit to Nairobi that he organized with a local cardiologist, six patients were waiting for him. “In Germany, they would all be considered emergencies,” Israel says. One eighty-year old grandmother had a heartrate of 18. “I’ve never before seen anything like this,” Israel exclaims. “At first I thought I couldn’t find her pulse before I realized that her heart was only beating once every three seconds.” After the surgery, she got up, dressed herself and hurriedly packed her bag, explaining she had a ton of work to accomplish. Her family was in disbelief, Israel says. “They told me she had been bedridden for five years because as soon as she tried to get up she would faint.”

Israel has been accused of racism, in thinking that these pacemakers are suitable for those in the global South even though they're considered to be trash by officials in wealthier countries. The cardiologist counters such criticism with stories about desperate need of his patients.

Carsten Israel

The hospital in Nairobi where Israel conducts the surgeries, charges patients $200 for the use of its facilities. If patients can’t afford that sum, Israel will pay it from the funds of his nonprofit. For some people, $200 far exceeds their resources. Once, a family from the extremely poor Northern region of Kenya told him they couldn’t afford the $3 for the bus ride to Nairobi. Israel suspected this was a pretense because they were afraid of the surgery and agreed to reimburse the $3, “but when they came, they were wearing rags and were so rail-thin, I understood that they really needed every cent they had for food.”

Israel is a renowned cardiologists in Germany. And yet, he considers his work in East Africa to be particularly meaningful. “Generally, most patients in Germany will get the treatment they need,” he says, “and I never before experienced that people have an illness that is easily curable but simply won’t be treated.” He also feels a heavy responsibility. Many patients have his personal cell phone and call him when they have problems or good news about how they’re doing.

Some of those progress reports come much faster than in Israel’s home country. Before he implanted a pacemaker in a tall Massai in Kenya, the man had been picked on by his family because he wouldn’t help much with the hard work on the family peanut farm. “When I examined him, he had a pulse of 40,” Israel says. “It’s a miracle he was even standing upright, let alone hauling heavy bags.” After the surgery, Israel advised his patient to stay the night for observation, but the patient couldn’t wait to leave. Two hours later, he returned, covered in sweat. He’d been running sprints with his brothers to test the new device. Israel shakes his head. In Germany, it would be unthinkable for a patient to engage in athletics immediately after surgery. But the patient was exuberant: “I was the fastest!”

The success stories are notable partly because the challenges remain so steep. In Zambia, for instance, there is a single cardiologist; she determined to become one after losing her younger sister to an easily curable heart disease. Often, the hospitals not only lack pacemakers but also sterile surgery equipment, antibiotics and other essential material. Therefore, Israel and his team import everything they need for the surgeries, including medication. If necessary, they improvise. “I’ve done surgery with a desk lamp hanging from the ceiling by threads,” Israel says. He already knows that he will need to return to Kenya in six months to replace the pacemaker of one of his patients and replace the batteries in others. If he doesn’t travel, lives are at risk.These technologies may help more animals and plants survive climate change

As the climate changes, the ripples will reach everywhere. Better data is needed for both plants and animals, and scientists are looking for genes that could allow crops to survive.

This article originally appeared in One Health/One Planet, a single-issue magazine that explores how climate change and other environmental shifts are making us more vulnerable to infectious diseases by land and by sea - and how scientists are working on solutions.

Along the west coast of South Florida and the Keys, Florida Bay is a nursery for young Caribbean spiny lobsters, a favorite local delicacy. Growing up in small shallow basins, they are especially vulnerable to warmer, more saline water. Climate change has brought tidal floods, bleached coral reefs and toxic algal blooms to the state, and since the 1990s, the population of the Caribbean spiny lobster has dropped some 20 percent, diminishing an important food for snapper, grouper, and herons, as well as people. In 1999, marine ecologist Donald Behringer discovered the first known virus among lobsters, Panulirus argus virus—about a quarter of juveniles die from it before they mature.

“When the water is warm PaV1 progresses much more quickly,” says Behringer, who is based at the Emerging Pathogens Institute at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Caribbean spiny lobsters are only one example of many species that are struggling in the era of climate change, both at sea and on land. As the oceans heat up, absorbing greenhouse gases and growing more acidic, marine diseases are emerging at an accelerated rate. Marine creatures are migrating to new places, and carrying pathogens with them. The latest grim report in the journal Science, states that if global warming continues at the current rate, the extinction of marine species will rival the Permian–Triassic extinction, sometimes called the “Great Dying,” when volcanoes poisoned the air and wiped out as much as 90 percent of all marine life 252 million years ago.

Similarly, on land, climate change has exposed wildlife, trees and crops to new or more virulent pathogens. Warming environments allow fungi, bacteria, viruses and infectious worms to proliferate in new species and locations or become more virulent. One paper modeling records of nearly 1,400 wildlife species projects that parasites will double by 2070 in the far north and in high-altitude places. Right now, we are seeing the effects most clearly on the fringes—along the coasts, up north and high in the mountains—but as the climate continues changing, the ripples will reach everywhere.

Few species are spared

On the Hawaiian Islands, mosquitoes are killing more songbirds. The dusky gray akikiki of Kauai and the chartreuse-yellow kiwikiu of Maui could vanish in two years, under assault from mosquitoes bearing avian malaria, according to a University of Hawaiʻi 2022 report. Previously, the birds could escape infection by roosting high in the cold mountains, where the pests couldn’t thrive, but climate change expanded the range of the mosquito and narrowed theirs.

Likewise, as more midge larvae survive over warm winters and breed better during drier summers, they bite more white-tailed deer, spreading often-fatal epizootic hemorrhagic disease. Especially in northern regions of the globe, climate change brings the threat of midges carrying blue tongue disease, a virus, to sheep and other animals. Tick-borne diseases like encephalitis and Lyme disease may become a greater threat to animals and perhaps humans.

"If you put all your eggs in one basket and then a pest comes a long, then you are more vulnerable to those risks," says Mehroad Ehsani, managing director of the food initiative in Africa for the Rockefeller Foundation. "Research is needed on resilient, climate smart, regenerative agriculture."

In the “thermal mismatch” theory of wildlife disease, cold-adapted species are at greater risk when their habitats warm, and warm-adapted species suffer when their habitats cool. Mammals can adjust their body temperature to adapt to some extent. Amphibians, fish and insects that cannot regulate body temperatures may be at greater risk. Many scientists see amphibians, especially, as canaries in the coalmine, signaling toxicity.

Early melting ice can foster disease. Climate models predict that the spring thaw will come ever-earlier in the lakes of the French Pyrenees, for instance, which traditionally stayed frozen for up to half the year. The tadpoles of the midwife toad live under the ice, where they are often infected with amphibian chytrid fungus. When a seven-year study tracked the virus in three species of amphibians in Pyrenees’s Lac Arlet, the research team found that, the earlier the spring thaw arrived, the more infection rates rose in common toads— , while remaining high among the midwife toads. But the team made another sad discovery: with early thaws, the common frog, which was thought to be free of the disease in Europe, also became infected with the fungus and died in large numbers.

Changing habitats affect animal behavior. Normally, spiny lobsters rely on chemical cues to avoid predators and sick lobsters. New conditions may be hampering their ability to “social distance”—which may help PaV1 spread, Behringer’s research suggests. Migration brings other risks. In April 2022, an international team led by scientists at Georgetown University announced the first comprehensive overview, published in the journal Nature, of how wild mammals under pressure from a changing climate may mingle with new populations and species—giving viruses a deadly opportunity to jump between hosts. Droughts, for example, will push animals to congregate at the few places where water remains.

Plants face threats also. At the timberline of the cold, windy, snowy mountains of the U.S. west, whitebark pine forests are facing a double threat, from white pine blister rust, a fungal disease, and multiplying pine beetles. “If we do nothing, we will lose the species,” says Robert Keane, a research ecologist for the U.S. Forest Service, based in Missoula, Montana. That would be a huge shift, he explains: “It’s a keystone species. There are over 110 animals that depend on it, many insects, and hundreds of plants.” In the past, beetle larvae would take two years to complete their lifecycle, and many died in frost. “With climate change, we're seeing more and more beetles survive, and sometimes the beetle can complete its lifecycle in one year,” he says.

Quintessential crops are under threat too

As some pathogens move north and new ones develop, they pose novel threats to the crops humans depend upon. This is already happening to wheat, coffee, bananas and maize.

Breeding against wheat stem rust, a fungus long linked to famine, was a key success in the mid-20th century Green Revolution, which brought higher yields around the world. In 2013, wheat stem rust reemerged in Germany after decades of absence. It ravaged both bread and durum wheat in Sicily in 2016 and has spread as far as England and Ireland. Wheat blast disease, caused by a different fungus, appeared in Bangladesh in 2016, and spread to India, the world’s second largest producer of wheat.

Insects, moths, worms, and coffee leaf rust—a fungus now found in all coffee-growing countries—threaten the livelihoods of millions of people who grow coffee, as well as everybody’s cup of joe. More heat, more intense rain, and higher humidity have allowed coffee leaf rust to cycle more rapidly. It has grown exponentially, overcoming the agricultural chemicals that once kept it under control.

To identify new diseases and fine-tune crops for resistance, scientists are increasingly relying on genomic tools.

Tar spot, a fungus native to Latin America that can cut corn production in half, has emerged in highland areas of Central Mexico and parts of the U.S.. Meanwhile, maize lethal necrosis disease has spread to multiple countries in Africa, notes Mehrdad Ehsani, Managing Director for the Food Initiative in Africa of the Rockefeller Foundation. The Cavendish banana, which most people eat today, was bred to be resistant to the fungus Panama 1. Now a new fungus, Panama 4, has emerged on every continent–including areas of Latin America that rely on the Cavendish for their income, reported a recent story in the Guardian. New threats are poised to emerge. Potato growers in the Andes Mountains have been shielded from disease because of colder weather at high altitude, but temperature fluxes and warming weather are expected to make this crop vulnerable to potato blight, found plant pathologist Erica Goss, at the Emerging Pathogens Institute.

Science seeks solutions

To protect food supplies in the era of climate change, scientists are calling for integrated global surveillance systems for crop disease outbreaks. “You can imagine that a new crop variety that is drought-tolerant could be susceptible to a pathogen that previous varieties had some resistance against,” Goss says. “Or a country suffers from a calamitous weather event, has to import seed from another country, and that seed is contaminated with a new pathogen or more virulent strain of an existing pathogen.” Researchers at the John Innes Center in Norwich and Aarhus University in Denmark have established ways to monitor wheat rust, for example.

Better data is essential, for both plants and animals. Historically, models of climate change predicted effects on plant pathogens based on mean temperatures, and scientists tracked plant responses to constant temperatures, explains Goss. “There is a need for more realistic tests of the effects of changing temperatures, particularly changes in daily high and low temperatures on pathogens,” she says.

To identify new diseases and fine-tune crops for resistance, scientists are increasingly relying on genomic tools. Goss suggests factoring the impact of climate change into those tools. Genomic efforts to select soft red winter wheat that is resistant to Fusarium head blight (FHB), a fungus that plagues farmers in the Southeastern U.S., have had early success. But temperature changes introduce a new factor.

A fundamental solution would be to bring back diversification in farming, says Ehsani. Thousands of plant species are edible, yet we rely on a handful. Wild relatives of domesticated crops are a store of possibly useful genes that may confer resistance to disease. The same is true for livestock. “If you put all your eggs in one basket and then a pest comes along, then you are more vulnerable to those risks. Research is needed on resilient, climate smart, regenerative agriculture,” Ehsani says.

Jonathan Sleeman, director of the U.S. Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center, has called for data on wildlife health to be systematically collected and integrated with climate and other variables because more comprehensive data will result in better preventive action. “We have focused on detecting diseases,” he says, but a more holistic strategy would apply human public health concepts to assuring animal wellbeing. (For example, one study asked experts to draw a diagram of relationships of all the factors affecting the health of a particular group of caribou.) We must not take the health of plants and animals for granted, because their vulnerability inevitably affects us too, Sleeman says. “We need to improve the resilience of wildlife populations so they can withstand the impact of climate change.”