I’m a Black, Genderqueer Medical Student: Here’s My Hard-Won Wisdom for Students and Educational Institutions

Advice follows for how to improve higher education for marginalized communities.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

In the last 12 years, I have earned degrees from Harvard College and Duke University and trained in an M.D.-Ph.D. program at the University of Pennsylvania. Through this process, I have assembled much educational privilege and can now speak with the authority that is conferred in these ivory towers. Along the way, as a Black, genderqueer, first-generation, low-income trainee, the systems of oppression that permeate American society—racism, transphobia, and classism, among others—coalesced in the microcosm of academia into a unique set of challenges that I had to navigate. I would like to share some of the lessons I have learned over the years in the format of advice for both Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) and LGBTQ+ trainees as well as members of the education institutions that seek to serve them.

To BIPOC and LGBTQ+ Trainees: Who you are is an asset, not an obstacle. Throughout my undergraduate years, I viewed my background as something to overcome. I had to overcome the instances of implicit bias and overt discrimination I experienced in my classes and among my peers. I had to overcome the preconceived, racialized, limitations on my abilities that academic advisors projected onto me as they characterized my course load as too ambitious or declared me unfit for medical school. I had to overcome the lack of social capital that comes with being from a low-resourced rural community and learn all the idiosyncrasies of academia from how to write professional emails to how and when to solicit feedback. I viewed my Blackness, queerness, and transness as inconveniences of identity that made my life harder.

It was only as I went on to graduate and medical school that I saw how much strength comes from who I am. My perspective allows me to conduct insightful, high-impact, and creative research that speaks to uplifting my various intersecting communities. My work on health equity for transgender people of color (TPOC) and BIPOC trainees in medicine is my form of advocacy. My publications are love letters to my communities, telling them that I see them and that I am with them. They are also indictments of the systems that oppress them and evidence that supports policy innovations and help move our society toward a more equitable future.

To Educators and Institutions: Allyship is active and uncomfortable. In the last 20 years, institutions have professed interest in diversifying their members and supporting marginalized groups. However, despite these proclamations, most have fallen short of truly allying themselves to communities in need of support. People often assume that allyship is defined by intent; that they are allies to Black people in the #BLM era because they, too, believe that Black lives have value. This is decency, not allyship. In the wake of the tragic killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, and the ongoing racial inequity of the COVID-19 pandemic, every person of color that I know in academia has been invited to a townhall on racism. These meetings risk re-traumatizing Black people if they feel coerced into sharing their experiences with racism in front of their white colleagues. This is exploitation, not allyship. These discussions must be carefully designed to prioritize Black voices but not depend on them. They must rely on shared responsibility for strategizing systemic change that centers the needs of Black and marginalized voices while diffusing the requisite labor across the entire institution.

Allyship requires a commitment to actions, not ideas. In education this is fostering safe environments for BIPOC and LGBTQ+ students. It is changing the culture of your institution such that anti-racism is a shared value and that work to establish anti-racist practices is distributed across all groups rather than just an additional tax on minority students and faculty. It is providing dedicated spaces for BIPOC and LGBTQ+ students where they can build community amongst themselves away from the gaze of majority white, heterosexual, and cisgender groups that dominate other spaces. It is also building the infrastructure to educate all members of your institution on issues facing BIPOC and LGBTQ+ students rather than relying on members of those communities to educate others through divulging their personal experiences.

Among well-intentioned ally hopefuls, anxiety can be a major barrier to action. Anxiety around the possibility of making a mistake, saying the wrong thing, hurting or offending someone, and having uncomfortable conversations. I'm here to alleviate any uncertainty around that: You will likely make mistakes, you may receive backlash, you will undoubtedly have uncomfortable conversations, and you may have to apologize. Steel yourself to that possibility and view it as an asset. People give their most unfiltered feedback when they have been hurt, so take that as an opportunity to guide change within your organizations and your own practices. How you respond to criticism will determine your allyship status. People are more likely to forgive when a commitment to change is quickly and repeatedly demonstrated.

The first step to moving forward in an anti-racist framework is to compensate the students for their labor in making the institution more inclusive.

To BIPOC and LGBTQ+ Trainees: Your labor is worth compensation and recognition. It is difficult to see your institution failing to adequately support members of your community without feeling compelled to act. As a Black person in medicine I have served on nearly every committee related to diversity recruitment and admissions. As a queer person I have sat on many taskforces dedicated to improving trans education in medical curricula. I have spent countless hours improving the institutions at which I have been educated and will likely spend countless more. However, over the past few years, I have realized that those hours do not generally advance my academic and professional goals. My peers who do not share in my marginalized identities do not have the external pressure to sequester large parts of their time for institutional change. While I was drafting emails to administrators or preparing journal clubs to educate students on trans health, my peers were studying.

There were periods in my education where there were appreciable declines in my grades and research productivity because of the time I spent on institutional reform. Without care, this phenomenon can translate to a perceived achievement gap. It is not that BIPOC and LGBTQ+ achieve less; in fact, in many ways we achieve more. However, we expend much of our effort on activities that are not traditionally valued as accomplishments for career advancement. The only way to change this norm is to start demanding compensation for your labor and respectfully declining if it is not provided. Compensation can be monetary, but it can also be opportunities for professional identity formation. For uncompensated work that I feel particularly compelled to do, I strategize how it can benefit me before starting the project. Can I write it up for publication in a peer-reviewed scientific journal? Can I find an advisor to support the task force and write a letter of reference on my behalf? Can I use the project to apply for external research funding or scholarships? These are all ways of translating the work that matters to you into the currency that the medical establishment values as productivity.

To Educators and Institutions: Compensate marginalized members of your organizations for making it better. Racism is the oldest institution in America. It is built into the foundation of the country and rests in the very top office in our nation's capital. Analogues of racism, specifically gender-based discrimination, transphobia, and classism, have similarly seeped into the fabric of our country and education system. Given their ubiquity, how can we expect to combat these issues cheaply? Today, anti-racism work is in vogue in academia, and institutions have looked to their Black and otherwise marginalized students to provide ways that the institution can improve. We, as students, regularly respond with well-researched, scholarly, actionable lists of specific interventions that are the result of dozens (sometimes hundreds) of hours of unpaid labor. Then, administrators dissect these interventions and scale them back citing budgetary concerns or hiring limitations.

It gives the impression that they view racism as an easy issue to fix, that can be slotted in under an existing line item, rather than the severe problem requiring radical reform that it actually is. The first step to moving forward in an anti-racist framework is to compensate the students for their labor in making the institution more inclusive. Inclusion and equity improve the educational environment for all students, so in the same way one would pay a consultant for an audit that identifies weaknesses in your institution, you should pay your students who are investing countless hours in strategic planning. While financial compensation is usually preferable, institutions can endow specific equity-related student awards, fellowships, and research programs that allow the work that students are already doing to help further their careers. Next, it is important to invest. Add anti-racism and equity interventions as specific items in departmental and institutional budgets so that there is annual reserved capital dedicated to these improvements, part of which can include the aforementioned student compensation.

To BIPOC and LGBTQ+ Trainees: Seek and be mentors. Early in my training, I often lamented the lack of mentors who shared important identities with myself. I initially sought a Black, queer mentor in medicine who could open doors and guide me from undergrad pre-med to university professor. Unfortunately, given the composition of the U.S. academy, this was not a realistic goal. While our white, cisgender, heterosexual colleagues can identify mentors they reflect, we have to operate on a different mentorship model. In my experience, it is more effective to assemble a mentorship network: a group of allies who facilitate your professional and personal development across one or more arenas. For me, as a physician-scholar-advocate, I need professional mentors who support my specific research interests, help me develop as a policy innovator and advocate, and who can guide my overall career trajectory on the short- and long- term time scales.

Rather than expecting one mentor to fulfill all those roles, as well as be Black and queer, I instead seek a set of mentors that can share in these roles, all of whom are informed or educable on the unique needs of Black and queer trainees. When assembling your own mentorship network, remember personal mentors who can help you develop self-care strategies and achieve work-life balance. Also, there is much value in peer mentorship. Some of my best mentors are my contemporaries. Your experiences have allowed you to accumulate knowledge—share that knowledge with each other.

To Educators and Institutions: Hire better mentors. Be better mentors. Poor mentorship is a challenge throughout academia that is amplified for BIPOC and LGBTQ+ trainees. Part of this challenge is due to priorities established in the hiring process. Institutions need to update hiring practices to explicitly evaluate faculty and staff candidates for their ability to be good mentors, particularly to students from marginalized communities. This can be achieved by including diverse groups of students on hiring committees and allowing them to interview candidates and assess how the candidate will support student needs. Also, continually evaluate current faculty and staff based on standardized feedback from students that will allow you to identify and intervene on deficits and continually improve the quality of mentorship at your institution.

The suggestions I provided are about navigating medical education, as it exists now. I hope that incorporating these practices will allow institutions to better serve the BIPOC and LGBTQ+ trainees that help make their communities vibrant. I also hope that my fellow BIPOC and LGBTQ+ trainees can see themselves in this conversation and feel affirmed and equipped in navigating medicine based on the tools I provide here. However, my words are only a tempering measure. True justice in medical education and health will only happen when we overhaul our institutions and dismantle systems of oppression in our society.

[Editor's Note: To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the beautifully designed e-reader version.]

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

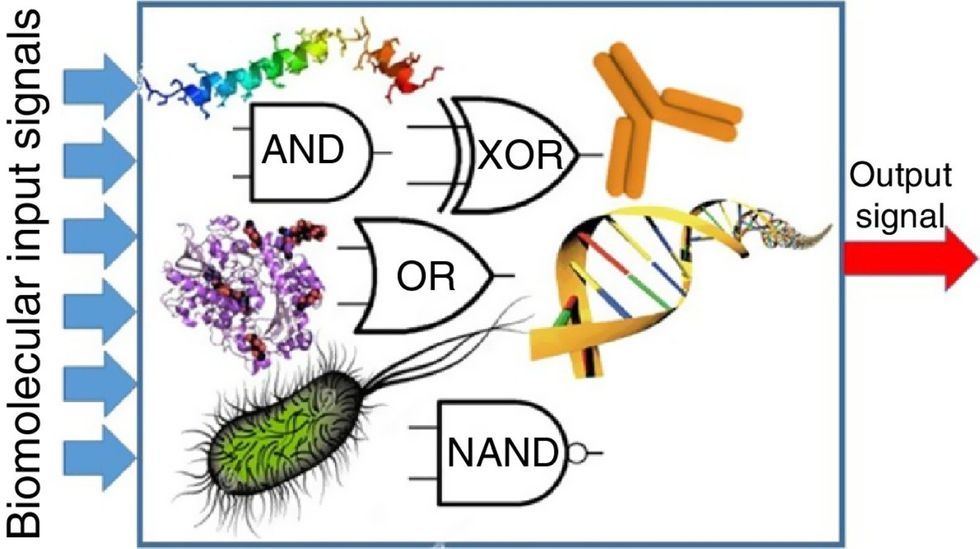

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.