Can tech help prevent the insect apocalypse?

Declining numbers of insects, coupled with climate change, can have devastating effects for people in more ways than one. But clever use of technologies like AI could keep them buzzing.

This article originally appeared in One Health/One Planet, a single-issue magazine that explores how climate change and other environmental shifts are making us more vulnerable to infectious diseases by land and by sea - and how scientists are working on solutions.

On a warm summer day, forests, meadows, and riverbanks should be abuzz with insects—from butterflies to beetles and bees. But bugs aren’t as abundant as they used to be, and that’s not a plus for people and the planet, scientists say. The declining numbers of insects, coupled with climate change, can have devastating effects for people in more ways than one. “Insects have been around for a very long time and can live well without humans, but humans cannot live without insects and the many services they provide to us,” says Philipp Lehmann, a researcher in the Department of Zoology at Stockholm University in Sweden. Their decline is not just bad, Lehmann adds. “It’s devastating news for humans.

”Insects and other invertebrates are the most diverse organisms on the planet. They fill most niches in terrestrial and aquatic environments and drive ecosystem functions. Many insects are also economically vital because they pollinate crops that humans depend on for food, including cereals, vegetables, fruits, and nuts. A paper published in PNAS notes that insects alone are worth more than $70 billion a year to the U.S. economy. In places where pollinators like honeybees are in decline, farmers now buy them from rearing facilities at steep prices rather than relying on “Mother Nature.”

And because many insects serve as food for other species—bats, birds and freshwater fish—they’re an integral part of the ecosystem’s food chain. “If you like to eat good food, you should thank an insect,” says Scott Hoffman Black, an ecologist and executive director of the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation in Portland, Oregon. “And if you like birds in your trees and fish in your streams, you should be concerned with insect conservation.”

Deforestation, urbanization, and agricultural spread have eaten away at large swaths of insect habitat. The increasingly poorly controlled use of insecticides, which harms unintended species, and the proliferation of invasive insect species that disrupt native ecosystems compound the problem.

“There is not a single reason why insects are in decline,” says Jessica L. Ware, associate curator in the Division of Invertebrate Zoology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and president of the Entomological Society of America. “There are over one million described insect species, occupying different niches and responding to environmental stressors in different ways.”

Jessica Ware, an entomologist at the American Museum of Natural History, is using DNA methods to monitor insects.

Credit:D.Finnin/AMNH

In addition to habitat loss fueling the decline in insect populations, the other “major drivers” Ware identified are invasive species, climate change, pollution, and fluctuating levels of nitrogen, which play a major role in the lifecycle of plants, some of which serve as insect habitants and others as their food. “The causes of world insect population declines are, unfortunately, very easy to link to human activities,” Lehmann says.

Climate change will undoubtedly make the problem worse. “As temperatures start to rise, it can essentially make it too hot for some insects to survive,” says Emily McDermott, an assistant professor in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology at the University of Arkansas. “Conversely in other areas, it could potentially also allow other insects to expand their ranges.”

Without Pollinators Humans Will Starve

We may not think much of our planet’s getting warmer by only one degree Celsius, but it can spell catastrophe for many insects, plants, and animals, because it’s often accompanied by less rainfall. “Changes in precipitation patterns will have cascading consequences across the tree of life,” says David Wagner, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut. Insects, in particular, are “very vulnerable” because “they’re small and susceptible to drying.”

For instance, droughts have put the monarch butterfly at risk of being unable to find nectar to “recharge its engine” as it migrates from Canada and New England to Mexico for winter, where it enters a hibernation state until it journeys back in the spring. “The monarch is an iconic and a much-loved insect,” whose migration “is imperiled by climate change,” Wagner says.

Warming and drying trends in the Western United States are perhaps having an even more severe impact on insects than in the eastern region. As a result, “we are seeing fewer individual butterflies per year,” says Matt Forister, a professor of insect ecology at the University of Nevada, Reno.

There are hundreds of butterfly species in the United States and thousands in the world. They are pollinators and can serve as good indicators of other species’ health. “Although butterflies are only one group among many important pollinators, in general we assume that what’s bad for butterflies is probably bad for other insects,” says Forister, whose research focuses on butterflies. Climate change and habitat destruction are wreaking havoc on butterflies as well as plants, leading to a further indirect effect on caterpillars and butterflies.

Different insect species have different levels of sensitivity to environmental changes. For example, one-half of the bumblebee species in the United States are showing declines, whereas the other half are not, says Christina Grozinger, a professor of entomology at the Pennsylvania State University. Some species of bumble bees are even increasing in their range, seemingly resilient to environmental changes. But other pollinators are dwindling to the point that farmers have to buy from the rearing facilities, which is the case for the California almond industry. “This is a massive cost to the farmer, which could be provided for free, in case the local habitats supported these pollinators,” Lehmann says.

For bees and other insects, climate change can harm the plants they depend on for survival or have a negative impact on the insects directly. Overly rainy and hot conditions may limit flowering in plants or reduce the ability of a pollinator to forage and feed, which then decreases their reproductive success, resulting in dwindling populations, Grozinger explains.

“Nutritional deprivation can also make pollinators more sensitive to viruses and parasites and therefore cause disease spread,” she says. “There are many ways that climate change can reduce our pollinator populations and make it more difficult to grow the many fruit, vegetable and nut crops that depend on pollinators.”

Disease-Causing Insects Can Bring More Outbreaks

While some much-needed insects are declining, certain disease-causing species may be spreading and proliferating, which is another reason for human concern. Many mosquito types spread malaria, Zika virus, West Nile virus, and a brain infection called equine encephalitis, along with other diseases as well as heartworms in dogs, says Michael Sabourin, president of the Vermont Entomological Society. An animal health specialist for the state, Sabourin conducts vector surveys that identify ticks and mosquitoes.

Scientists refer to disease-carrying insects as vector species and, while there’s a limited number of them, many of these infections can be deadly. Fleas were a well-known vector for the bubonic plague, while kissing bugs are a vector for Chagas disease, a potentially life-threatening parasitic illness in humans, dogs, and other mammals, Sabourin says.

As the planet heats up, some of the creepy crawlers are able to survive milder winters or move up north. Warmer temperatures and a shorter snow season have spawned an increasing abundance of ticks in Maine, including the blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis), known to transmit Lyme disease, says Sean Birkel, an assistant professor in the Climate Change Institute and Cooperative Extension at the University of Maine.

Coupled with more frequent and heavier precipitation, rising temperatures bring a longer warm season that can also lead to a longer period of mosquito activity. “While other factors may be at play, climate change affects important underlying conditions that can, in turn, facilitate the spread of vector-borne disease,” Birkel says.

For example, if mosquitoes are finding fewer of their preferred food sources, they may bite humans more. Both male and female mosquitoes feed on sugar as part of their normal behavior, but if they aren’t eating their fill, they may become more bloodthirsty. One recent paper found that sugar-deprived Anopheles gambiae females go for larger blood meals to stay in good health and lay eggs. “More blood meals equals more chances to pick up and transmit a pathogen,” McDermott says, He adds that climate change could reduce the number of available plants to feed on. And while most mosquitoes are “generalist sugar-feeders” meaning that they will likely find alternatives, losing their favorite plants can make them hungrier for blood.

Similar to the effect of losing plants, mosquitoes may get turned onto people if they lose their favorite animal species. For example, some studies found that Culex pipiens mosquitoes that transmit the West Nile virus feed primarily on birds in summer. But that changes in the fall, at least in some places. Because there are fewer birds around, C. pipiens switch to mammals, including humans. And if some disease-carrying insect species proliferate or increase their ranges, that increases chances for human infection, says McDermott. “A larger concern is that climate change could increase vector population sizes, making it more likely that people or animals would be bitten by an infected insect.”

Science Can Help Bring Back the Buzz

To help friendly insects thrive and keep the foes in check, scientists need better ways of trapping, counting, and monitoring insects. It’s not an easy job, but artificial intelligence and molecular methods can help. Ware’s lab uses various environmental DNA methods to monitor freshwater habitats. Molecular technologies hold much promise. The so-called DNA barcodes, in which species are identified using a short string of their genes, can now be used to identify birds, bees, moths and other creatures, and should be used on a larger scale, says Wagner, the University of Connecticut professor. “One day, something akin to Star Trek’s tricorder will soon be on sale down at the local science store.”

Scientists are also deploying artificial intelligence, or AI, to identify insects in agricultural systems and north latitudes where there are fewer bugs, Wagner says. For instance, some automated traps already use the wingbeat frequencies of mosquitoes to distinguish the harmless ones from the disease-carriers. But new technology and software are needed to further expand detection based on vision, sound, and odors.

“Because of their ubiquity, enormity of numbers, and seemingly boundless diversity, we desperately need to develop molecular and AI technologies that will allow us to automate sampling and identification,” says Wagner. “That would accelerate our ability to track insect populations, alert us to the presence of new disease vectors, exotic pest introductions, and unexpected declines.”

Doctors worry that fungal pathogens may cause the next pandemic.

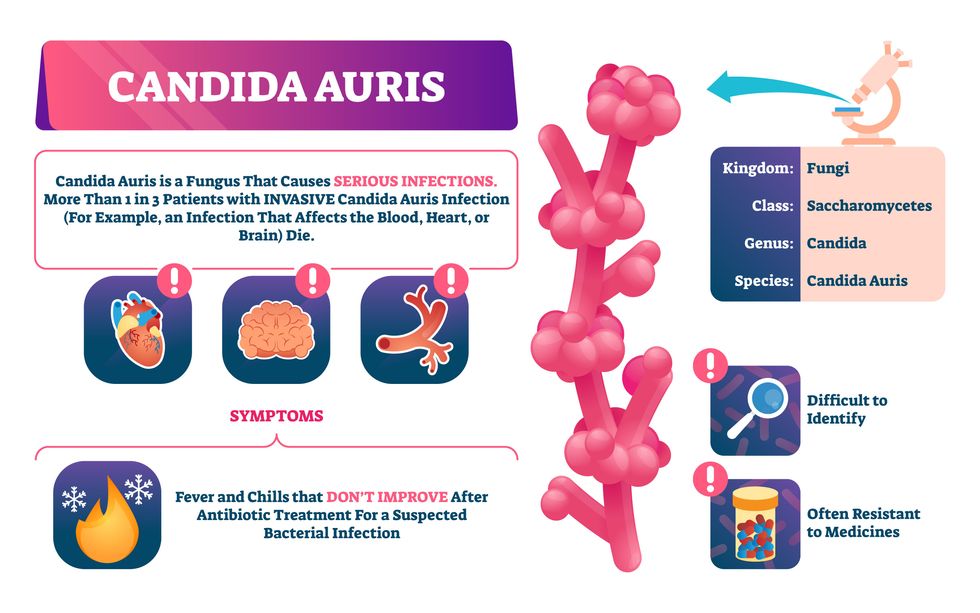

Bacterial antibiotic resistance has been a concern in the medical field for several years. Now a new, similar threat is arising: drug-resistant fungal infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers antifungal and antimicrobial resistance to be among the world’s greatest public health challenges.

One particular type of fungal infection caused by Candida auris is escalating rapidly throughout the world. And to make matters worse, C. auris is becoming increasingly resistant to current antifungal medications, which means that if you develop a C. auris infection, the drugs your doctor prescribes may not work. “We’re effectively out of medicines,” says Thomas Walsh, founding director of the Center for Innovative Therapeutics and Diagnostics, a translational research center dedicated to solving the antimicrobial resistance problem. Walsh spoke about the challenges at a Demy-Colton Virtual Salon, one in a series of interactive discussions among life science thought leaders.

Although C. auris typically doesn’t sicken healthy people, it afflicts immunocompromised hospital patients and may cause severe infections that can lead to sepsis, a life-threatening condition in which the overwhelmed immune system begins to attack the body’s own organs. Between 30 and 60 percent of patients who contract a C. auris infection die from it, according to the CDC. People who are undergoing stem cell transplants, have catheters or have taken antifungal or antibiotic medicines are at highest risk. “We’re coming to a perfect storm of increasing resistance rates, increasing numbers of immunosuppressed patients worldwide and a bug that is adapting to higher temperatures as the climate changes,” says Prabhavathi Fernandes, chair of the National BioDefense Science Board.

Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures.

Although medical professionals aren’t concerned at this point about C. auris evolving to affect healthy people, they worry that its presence in hospitals can turn routine surgeries into life-threatening calamities. “It’s coming,” says Fernandes. “It’s just a matter of time.”

An emerging global threat

“Fungi are found in the environment,” explains Fernandes, so Candida spores can easily wind up on people’s skin. In hospitals, they can be transferred from contact with healthcare workers or contaminated surfaces. Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures. It can enter the body during medical treatments that break the skin—and cause an infection. Overall, fungal infections cost some $48 billion in the U.S. each year. And infection rates are increasing because, in an ironic twist, advanced medical therapies are enabling severely ill patients to live longer and, therefore, be exposed to this pathogen.

The first-ever case of a C. auris infection was reported in Japan in 2009, although an analysis of Candida samples dated the earliest strain to a 1996 sample from South Korea. Since then, five separate varieties – called clades, which are similar to strains among bacteria – developed independently in different geographies: South Asia, East Asia, South Africa, South America and, recently, Iran. So far, C. auris infections have been reported in 35 countries.

In the U.S., the first infection was reported in 2016, and the CDC started tracking it nationally two years later. During that time, 5,654 cases have been reported to the CDC, which only tracks U.S. data.

What’s more notable than the number of cases is their rate of increase. In 2016, new cases increased by 175 percent and, on average, they have approximately doubled every year. From 2016 through 2022, the number of infections jumped from 63 to 2,377, a roughly 37-fold increase.

“This reminds me of what we saw with epidemics from 2013 through 2020… with Ebola, Zika and the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Robin Robinson, CEO of Spriovas and founding director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. These epidemics started with a hockey stick trajectory, Robinson says—a gradual growth leading to a sharp spike, just like the shape of a hockey stick.

Another challenge is that right now medics don’t have rapid diagnostic tests for fungal infections. Currently, patients are often misdiagnosed because C. auris resembles several other easily treated fungi. Or they are diagnosed long after the infection begins and is harder to treat.

The problem is that existing diagnostics tests can only identify C. auris once it reaches the bloodstream. Yet, because this pathogen infects bodily tissues first, it should be possible to catch it much earlier before it becomes life-threatening. “We have to diagnose it before it reaches the bloodstream,” Walsh says.

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics.

“We need to focus on rapid diagnostic tests that do not rely on a positive blood culture,” says John Sperzel, president and CEO of T2 Biosystems, a company specializing in diagnostics solutions. Blood cultures typically take two to three days for the concentration of Candida to become large enough to detect. The company’s novel test detects about 90 percent of Candida species within three to five hours—thanks to its ability to spot minute quantities of the pathogen in blood samples instead of waiting for them to incubate and proliferate.

Unlike other Candida species C. auris thrives at human body temperatures

Adobe Stock

Tackling the resistance challenge

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics. The number of cases that stopped responding to echinocandin, the first-line therapy for most Candida infections, tripled in 2020, according to a study by the CDC.

Now, each of the first four clades shows varying levels of resistance to all three commonly prescribed classes of antifungal medications, such as azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes. For example, 97 percent of infections from C. auris Clade I are resistant to fluconazole, 54 percent to voriconazole and 30 percent of amphotericin. Nearly half are resistant to multiple antifungal drugs. Even with Clade II fungi, which has the least resistance of all the clades, 11 to 14 percent have become resistant to fluconazole.

Anti-fungal therapies typically target specific chemical compounds present on fungi’s cell membranes, but not on human cells—otherwise the medicine would cause damage to our own tissues. Fluconazole and other azole antifungals target a compound called ergosterol, preventing the fungal cells from replicating. Over the years, however, C. auris evolved to resist it, so existing fungal medications don’t work as well anymore.

A newer class of drugs called echinocandins targets a different part of the fungal cell. “The echinocandins – like caspofungin – inhibit (a part of the fungi) involved in making glucan, which is an essential component of the fungal cell wall and is not found in human cells,” Fernandes says. New antifungal treatments are needed, she adds, but there are only a few magic bullets that will hit just the fungus and not the human cells.

Research to fight infections also has been challenged by a lack of government support. That is changing now that BARDA is requesting proposals to develop novel antifungals. “The scope includes C. auris, as well as antifungals following a radiological/nuclear emergency, says BARDA spokesperson Elleen Kane.

The remaining challenge is the number of patients available to participate in clinical trials. Large numbers are needed, but the available patients are quite sick and often die before trials can be completed. Consequently, few biopharmaceutical companies are developing new treatments for C. auris.

ClinicalTrials.gov reports only two drugs in development for invasive C. auris infections—those than can spread throughout the body rather than localize in one particular area, like throat or vaginal infections: ibrexafungerp by Scynexis, Inc., fosmanogepix, by Pfizer.

Scynexis’ ibrexafungerp appears active against C. auris and other emerging, drug-resistant pathogens. The FDA recently approved it as a therapy for vaginal yeast infections and it is undergoing Phase III clinical trials against invasive candidiasis in an attempt to keep the infection from spreading.

“Ibreafungerp is structurally different from other echinocandins,” Fernandes says, because it targets a different part of the fungus. “We’re lucky it has activity against C. auris.”

Pfizer’s fosmanogepix is in Phase II clinical trials for patients with invasive fungal infections caused by multiple Candida species. Results are showing significantly better survival rates for people taking fosmanogepix.

Although C. auris does pose a serious threat to healthcare worldwide, scientists try to stay optimistic—because they recognized the problem early enough, they might have solutions in place before the perfect storm hits. “There is a bit of hope,” says Robinson. “BARDA has finally been able to fund the development of new antifungal agents and, hopefully, this year we can get several new classes of antifungals into development.”

New elevators could lift up our access to space

A space elevator would be cheaper and cleaner than using rockets

Story by Big Think

When people first started exploring space in the 1960s, it cost upwards of $80,000 (adjusted for inflation) to put a single pound of payload into low-Earth orbit.

A major reason for this high cost was the need to build a new, expensive rocket for every launch. That really started to change when SpaceX began making cheap, reusable rockets, and today, the company is ferrying customer payloads to LEO at a price of just $1,300 per pound.

This is making space accessible to scientists, startups, and tourists who never could have afforded it previously, but the cheapest way to reach orbit might not be a rocket at all — it could be an elevator.

The space elevator

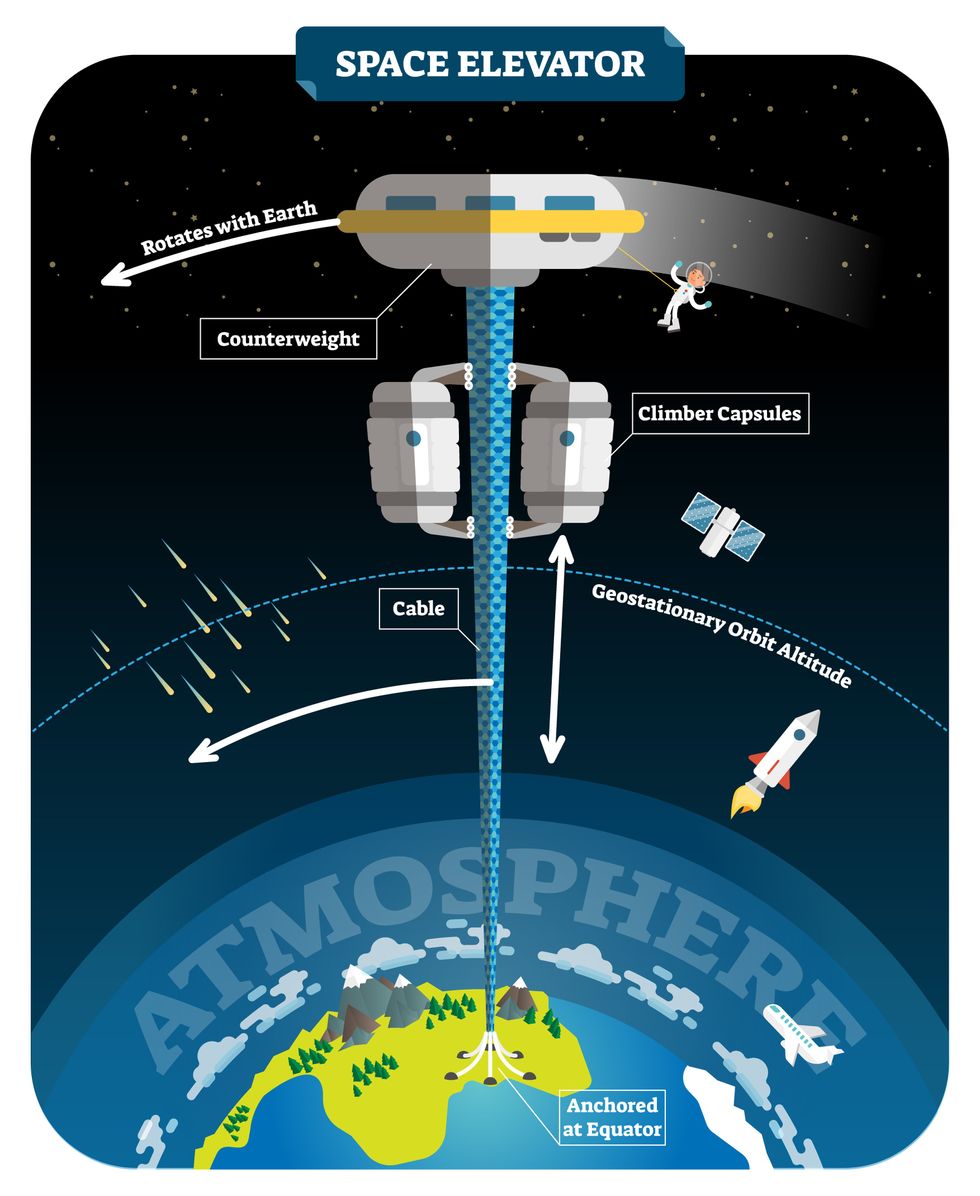

The seeds for a space elevator were first planted by Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1895, who, after visiting the 1,000-foot (305 m) Eiffel Tower, published a paper theorizing about the construction of a structure 22,000 miles (35,400 km) high.

This would provide access to geostationary orbit, an altitude where objects appear to remain fixed above Earth’s surface, but Tsiolkovsky conceded that no material could support the weight of such a tower.

We could then send electrically powered “climber” vehicles up and down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit.

In 1959, soon after Sputnik, Russian engineer Yuri N. Artsutanov proposed a way around this issue: instead of building a space elevator from the ground up, start at the top. More specifically, he suggested placing a satellite in geostationary orbit and dropping a tether from it down to Earth’s equator. As the tether descended, the satellite would ascend. Once attached to Earth’s surface, the tether would be kept taut, thanks to a combination of gravitational and centrifugal forces.

We could then send electrically powered “climber” vehicles up and down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit. According to physicist Bradley Edwards, who researched the concept for NASA about 20 years ago, it’d cost $10 billion and take 15 years to build a space elevator, but once operational, the cost of sending a payload to any Earth orbit could be as low as $100 per pound.

“Once you reduce the cost to almost a Fed-Ex kind of level, it opens the doors to lots of people, lots of countries, and lots of companies to get involved in space,” Edwards told Space.com in 2005.

In addition to the economic advantages, a space elevator would also be cleaner than using rockets — there’d be no burning of fuel, no harmful greenhouse emissions — and the new transport system wouldn’t contribute to the problem of space junk to the same degree that expendable rockets do.

So, why don’t we have one yet?

Tether troubles

Edwards wrote in his report for NASA that all of the technology needed to build a space elevator already existed except the material needed to build the tether, which needs to be light but also strong enough to withstand all the huge forces acting upon it.

The good news, according to the report, was that the perfect material — ultra-strong, ultra-tiny “nanotubes” of carbon — would be available in just two years.

“[S]teel is not strong enough, neither is Kevlar, carbon fiber, spider silk, or any other material other than carbon nanotubes,” wrote Edwards. “Fortunately for us, carbon nanotube research is extremely hot right now, and it is progressing quickly to commercial production.”Unfortunately, he misjudged how hard it would be to synthesize carbon nanotubes — to date, no one has been able to grow one longer than 21 inches (53 cm).

Further research into the material revealed that it tends to fray under extreme stress, too, meaning even if we could manufacture carbon nanotubes at the lengths needed, they’d be at risk of snapping, not only destroying the space elevator, but threatening lives on Earth.

Looking ahead

Carbon nanotubes might have been the early frontrunner as the tether material for space elevators, but there are other options, including graphene, an essentially two-dimensional form of carbon that is already easier to scale up than nanotubes (though still not easy).

Contrary to Edwards’ report, Johns Hopkins University researchers Sean Sun and Dan Popescu say Kevlar fibers could work — we would just need to constantly repair the tether, the same way the human body constantly repairs its tendons.

“Using sensors and artificially intelligent software, it would be possible to model the whole tether mathematically so as to predict when, where, and how the fibers would break,” the researchers wrote in Aeon in 2018.

“When they did, speedy robotic climbers patrolling up and down the tether would replace them, adjusting the rate of maintenance and repair as needed — mimicking the sensitivity of biological processes,” they continued.Astronomers from the University of Cambridge and Columbia University also think Kevlar could work for a space elevator — if we built it from the moon, rather than Earth.

They call their concept the Spaceline, and the idea is that a tether attached to the moon’s surface could extend toward Earth’s geostationary orbit, held taut by the pull of our planet’s gravity. We could then use rockets to deliver payloads — and potentially people — to solar-powered climber robots positioned at the end of this 200,000+ mile long tether. The bots could then travel up the line to the moon’s surface.

This wouldn’t eliminate the need for rockets to get into Earth’s orbit, but it would be a cheaper way to get to the moon. The forces acting on a lunar space elevator wouldn’t be as strong as one extending from Earth’s surface, either, according to the researchers, opening up more options for tether materials.

“[T]he necessary strength of the material is much lower than an Earth-based elevator — and thus it could be built from fibers that are already mass-produced … and relatively affordable,” they wrote in a paper shared on the preprint server arXiv.

After riding up the Earth-based space elevator, a capsule would fly to a space station attached to the tether of the moon-based one.

Electrically powered climber capsules could go up down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit.

Adobe Stock

Some Chinese researchers, meanwhile, aren’t giving up on the idea of using carbon nanotubes for a space elevator — in 2018, a team from Tsinghua University revealed that they’d developed nanotubes that they say are strong enough for a tether.

The researchers are still working on the issue of scaling up production, but in 2021, state-owned news outlet Xinhua released a video depicting an in-development concept, called “Sky Ladder,” that would consist of space elevators above Earth and the moon.

After riding up the Earth-based space elevator, a capsule would fly to a space station attached to the tether of the moon-based one. If the project could be pulled off — a huge if — China predicts Sky Ladder could cut the cost of sending people and goods to the moon by 96 percent.

The bottom line

In the 120 years since Tsiolkovsky looked at the Eiffel Tower and thought way bigger, tremendous progress has been made developing materials with the properties needed for a space elevator. At this point, it seems likely we could one day have a material that can be manufactured at the scale needed for a tether — but by the time that happens, the need for a space elevator may have evaporated.

Several aerospace companies are making progress with their own reusable rockets, and as those join the market with SpaceX, competition could cause launch prices to fall further.

California startup SpinLaunch, meanwhile, is developing a massive centrifuge to fling payloads into space, where much smaller rockets can propel them into orbit. If the company succeeds (another one of those big ifs), it says the system would slash the amount of fuel needed to reach orbit by 70 percent.

Even if SpinLaunch doesn’t get off the ground, several groups are developing environmentally friendly rocket fuels that produce far fewer (or no) harmful emissions. More work is needed to efficiently scale up their production, but overcoming that hurdle will likely be far easier than building a 22,000-mile (35,400-km) elevator to space.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.