Scientists are making machines, wearable and implantable, to act as kidneys

Recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen soon.

Like all those whose kidneys have failed, Scott Burton’s life revolves around dialysis. For nearly two decades, Burton has been hooked up (or, since 2020, has hooked himself up at home) to a dialysis machine that performs the job his kidneys normally would. The process is arduous, time-consuming, and expensive. Except for a brief window before his body rejected a kidney transplant, Burton has depended on machines to take the place of his kidneys since he was 12-years-old. His whole life, the 39-year-old says, revolves around dialysis.

“Whenever I try to plan anything, I also have to plan my dialysis,” says Burton says, who works as a freelance videographer and editor. “It’s a full-time job in itself.”

Many of those on dialysis are in line for a kidney transplant that would allow them to trade thrice-weekly dialysis and strict dietary limits for a lifetime of immunosuppressants. Burton’s previous transplant means that his body will likely reject another donated kidney unless it matches perfectly—something he’s not counting on. It’s why he’s enthusiastic about the development of artificial kidneys, small wearable or implantable devices that would do the job of a healthy kidney while giving users like Burton more flexibility for traveling, working, and more.

Still, the devices aren’t ready for testing in humans—yet. But recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen soon, according to Jonathan Himmelfarb, a nephrologist at the University of Washington.

“It would liberate people with kidney failure,” Himmelfarb says.

An engineering marvel

Compared to the heart or the brain, the kidney doesn’t get as much respect from the medical profession, but its job is far more complex. “It does hundreds of different things,” says UCLA’s Ira Kurtz.

Kurtz would know. He’s worked as a nephrologist for 37 years, devoting his career to helping those with kidney disease. While his colleagues in cardiology and endocrinology have seen major advances in the development of artificial hearts and insulin pumps, little has changed for patients on hemodialysis. The machines remain bulky and require large volumes of a liquid called dialysate to remove toxins from a patient’s blood, along with gallons of purified water. A kidney transplant is the next best thing to someone’s own, functioning organ, but with over 600,000 Americans on dialysis and only about 100,000 kidney transplants each year, most of those in kidney failure are stuck on dialysis.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. To build an artificial heart, Kurtz says, you basically need to engineer a pump. An artificial pancreas needs to balance blood sugar levels with insulin secretion. While neither of these tasks is simple, they are fairly straightforward. The kidney, on the other hand, does more than get rid of waste products like urea and other toxins. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different, helping to regulate electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and phosphorous; maintaining blood pressure and water balance; guiding the body’s hormonal and inflammatory responses; and aiding in the formation of red blood cells.

There's been little progress for patients during Ira Kurtz's 37 years as a nephrologist. Artificial kidneys would change that.

UCLA

Dialysis primarily filters waste, and does so well enough to keep someone alive, but it isn’t a true artificial kidney because it doesn’t perform the kidney’s other jobs, according to Kurtz, such as sensing levels of toxins, wastes, and electrolytes in the blood. Due to the size and water requirements of existing dialysis machines, the equipment isn’t portable. Physicians write a prescription for a certain duration of dialysis and assess how well it’s working with semi-regular blood tests. The process of dialysis itself, however, is conducted blind. Doctors can’t tell how much dialysis a patient needs based on kidney values at the time of treatment, says Meera Harhay, a nephrologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

But it’s the impact of dialysis on their day-to-day lives that creates the most problems for patients. Only one-quarter of those on dialysis are able to remain employed (compared to 85% of similar-aged adults), and many report a low quality of life. Having more flexibility in life would make a major different to her patients, Harhay says.

“Almost half their week is taken up by the burden of their treatment. It really eats away at their freedom and their ability to do things that add value to their life,” she says.

Art imitates life

The challenge for artificial kidney designers was how to compress the kidney’s natural functions into a portable, wearable, or implantable device that wouldn’t need constant access to gallons of purified and sterilized water. The other universal challenge they faced was ensuring that any part of the artificial kidney that would come in contact with blood was kept germ-free to prevent infection.

As part of the 2021 KidneyX Prize, a partnership between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the American Society of Nephrology, inventors were challenged to create prototypes for artificial kidneys. Himmelfarb’s team at the University of Washington’s Center for Dialysis Innovation won the prize by focusing on miniaturizing existing technologies to create a portable dialysis machine. The backpack sized AKTIV device (Ambulatory Kidney to Increase Vitality) will recycle dialysate in a closed loop system that removes urea from blood and uses light-based chemical reactions to convert the urea to nitrogen and carbon dioxide, which allows the dialysate to be recirculated.

Himmelfarb says that the AKTIV can be used when at home, work, or traveling, which will give users more flexibility and freedom. “If you had a 30-pound device that you could put in the overhead bins when traveling, you could go visit your grandkids,” he says.

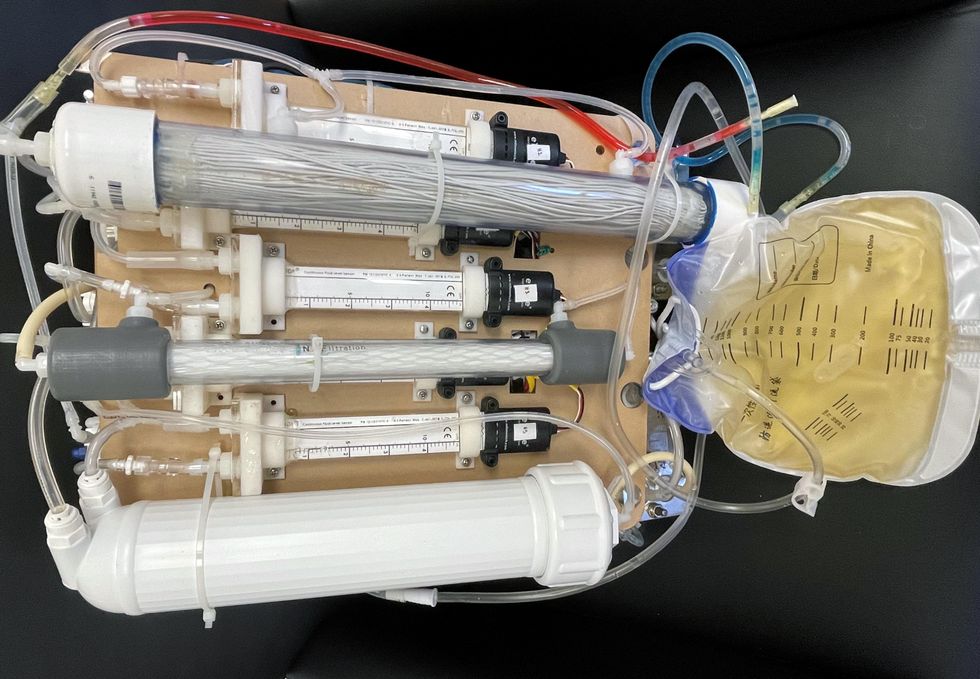

Kurtz’s team at UCLA partnered with the U.S. Kidney Research Corporation and Arkansas University to develop a dialysate-free desktop device (about the size of a small printer) as the first phase of a progression that will he hopes will lead to something small and implantable. Part of the reason for the artificial kidney’s size, Kurtz says, is the number of functions his team are cramming into it. Not only will it filter urea from blood, but it will also use electricity to help regulate electrolyte levels in a process called electrodeionization. Kurtz emphasizes that these additional functions are what makes his design a true artificial kidney instead of just a small dialysis machine.

One version of an artificial kidney.

UCLA

“It doesn't have just a static function. It has a bank of sensors that measure chemicals in the blood and feeds that information back to the device,” Kurtz says.

Other startups are getting in on the game. Nephria Bio, a spinout from the South Korean-based EOFlow, is working to develop a wearable dialysis device, akin to an insulin pump, that uses miniature cartridges with nanomaterial filters to clean blood (Harhay is a scientific advisor to Nephria). Ian Welsford, Nephria’s co-founder and CTO, says that the device’s design means that it can also be used to treat acute kidney injuries in resource-limited settings. These potentials have garnered interest and investment in artificial kidneys from the U.S. Department of Defense.

For his part, Burton is most interested in an implantable device, as that would give him the most freedom. Even having a regular outpatient procedure to change batteries or filters would be a minor inconvenience to him.

“Being plugged into a machine, that’s not mimicking life,” he says.

This article was first published by Leaps.org on May 5, 2022.

7 Reasons Why We Should Not Need Boosters for COVID-19

A top infectious disease physician explains why immunity derived from natural infection and the vaccines should be long-lasting.

There are at least 7 reasons why immunity after vaccination or infection with COVID-19 should likely be long-lived. If durable, I do not think boosters will be necessary in the future, despite CEOs of pharmaceutical companies (who stand to profit from boosters) messaging that they may and readying such boosters. To explain these reasons, let's orient ourselves to the main components of the immune system.

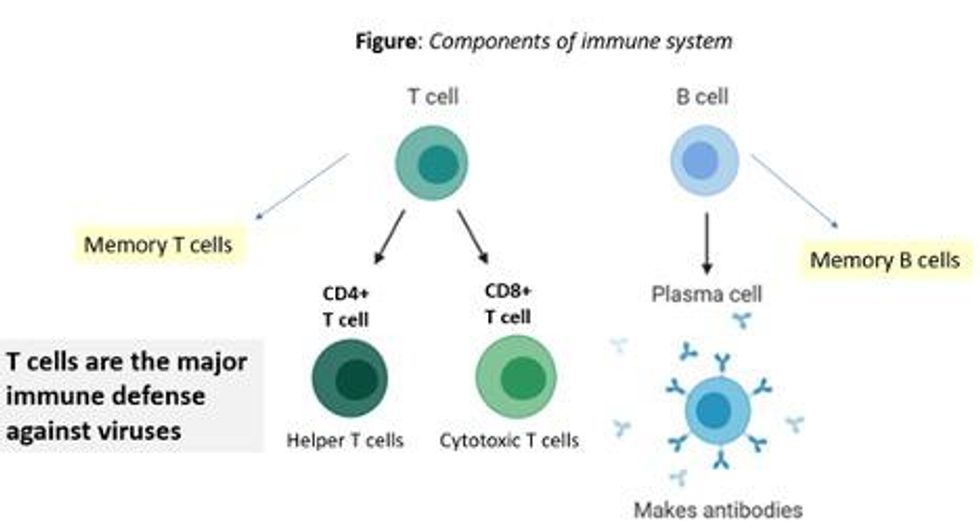

There are two major arms of the immune system: B cells (which produce antibodies) and T cells (which are formed specifically to attack and kill pathogens). T cells are divided into two types, CD4 cells ("helper" T cells) and CD8 cells ("cytotoxic" T cells).

Each arm, once stimulated by infection or vaccine, should hopefully make "memory" banks. So if the body sees the pathogen in the future, these defenses should come roaring back to attack the virus and protect you from getting sick. Plenty of research in COVID-19 indicates a likely long-lasting response to the vaccine or infection. Here are seven of the most compelling reasons:

REASON 1: Memory B Cells Are Produced By Vaccines and Natural Infection

In one study, 12 volunteers who had never had Covid-19--and were fully vaccinated with two Pfizer/BioNTech shots-- underwent biopsies of their lymph nodes. This is where memory B cells are stored in places called "germinal centers". The biopsies were performed three, four, six, and seven weeks after the first mRNA vaccine shot, and were stained to reveal that germinal center memory B cells in the lymph nodes increased in concentration over time.

Natural infection also generates memory B cells. Even after antibody levels wane over time, strong memory B cells were detected in the blood of individuals six and eight months after infection in different studies. Indeed, the half-lives of the memory B cells seen in the study examining patients 8 months after COVID-19 led the authors to conclude that "B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 was robust and is likely long-lasting." Reason #2 tells us that memory B cells can be active for a very long time indeed.

REASON #2: Memory B Cells Can Produce Neutralizing Antibodies If They See Infection Again Decades Later

Demonstrated production of memory B cells after vaccination or natural infection with COVID-19 is so important because memory B cells, once generated, can be activated to produce high levels of neutralizing antibodies against the pathogen even if encountered many years after the initial exposure. In one amazing study (published in 2008), researchers isolated memory B cells against the 1918 flu strain from the blood of 32 individuals aged 91-101 years. These people had been born on or before 1915 and had survived that pandemic.

Their memory B cells, when exposed to the 1918 flu strain in a test tube, generated high levels of neutralizing antibodies against the virus -- antibodies that then protected mice from lethal infection with this deadly strain. The ability of memory B cells to produce complex antibody responses against an infection nine decades after exposure speaks to their durability.

REASON #3: Vaccines or Natural Infection Trigger Strong Memory T Cell Immunity

All of the trials of the major COVID-19 vaccine candidates measured strong T cell immunity following vaccination, most often assessed by measuring SARS-CoV-2 specific T cells in the phase I/II safety and immunogenicity studies. There are a number of studies that demonstrate the production of strong T cell immunity to COVID-19 after natural infection as well, even when the infection was mild or asymptomatic.

The same study that showed us robust memory B cell production 8 months after natural infection also demonstrated strong and sustained memory T cell production. In fact, the half-lives of the memory T cells in this cohort were long (~125-225 days for CD8+ and ~94-153 days for CD4+ T cells), comparable to the 123-day half-life observed for memory CD8+ T cells after yellow fever immunization (a vaccine usually given once over a lifetime).

A recent study of individuals recovered from COVID-19 show that the initial T cells generated by natural infection mature and differentiate over time into memory T cells that will be "put in the bank" for sustained periods.

REASON #4: T Cell Immunity Following Vaccinations for Other Infections Is Long-Lasting

Last year, we were fortunate to be able to measure how T cell immunity is generated by COVID-19 vaccines, which was not possible in earlier eras when vaccine trials were done for other infections (such as measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, diphtheria). Antibodies are just the "tip of the iceberg" when assessing the response to vaccination, but were the only arm of the immune response that could be measured following vaccination in the past.

Measuring pathogen-specific T cell responses takes sophisticated technology. However, T cell responses, when assessed years after vaccination for other pathogens, has been shown to be long-lasting. For example, in one study of 56 volunteers who had undergone measles vaccination when they were much younger, strong CD8 and CD4 cell responses to vaccination could be detected up to 34 years later.

REASON #5: T Cell Immunity to Related Coronaviruses That Caused Severe Disease is Long-Lasting

SARS-CoV-2 is a coronavirus that causes severe disease, unlike coronaviruses that cause the common cold. Two other coronaviruses in the recent past caused severe disease, specifically Severely Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (SARS) in late 2002-2003 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2011.

A study performed in 2020 demonstrated that the blood of 23 recovered SARS patients possess long-lasting memory T cells that were still reactive to SARS 17 years after the outbreak in 2003. Many scientists expect that T cell immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will be equally durable to that of its cousin.

REASON #6: T Cell Responses from Vaccination and Natural Infection With the Ancestral Strain of COVID-19 Are Robust Against Variants

Even though antibody responses from vaccination may be slightly lower against various COVID-19 variants of concern that have emerged in recent months, T cell immunity after vaccination has been shown to be unperturbed by mutations in the spike protein (in the variants). For instance, T cell responses after mRNA vaccines maintained strong activity against different variants (including P.1 Brazil variant, B.1.1.7 UK variant, B.1.351 South Africa variant and the CA.20.C California variant) in a recent study.

Another study showed that the vaccines generated robust T cell immunity that was unfazed by different variants, including B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. The CD4 and CD8 responses generated after natural infection are equally robust, showing activity against multiple "epitopes" (little segments) of the spike protein of the virus. For instance, CD8 cells responds to 52 epitopes and CD4 cells respond to 57 epitopes across the spike protein, so that a few mutations in the variants cannot knock out such a robust and in-breadth T cell response. Indeed, a recent paper showed that mRNA vaccines were 97.4 percent effective against severe COVID-19 disease in Qatar, even when the majority of circulating virus there was from variants of concern (B.1.351 and B.1.1.7).

REASON #7: Coronaviruses Don't Mutate Quickly Like Influenza, Which Requires Annual Booster Shots

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses, like influenza and HIV (which is actually a retrovirus), but do not mutate as quickly as either one. The reason that coronaviruses don't mutate very rapidly is that their replicating mechanism (polymerase) has a strong proofreading mechanism: If the virus mutates, it usually goes back and self-corrects. Mutations can arise with high rates of replication when transmission is very frequent -- as has been seen in recent months with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants during surges. However, the COVID-19 virus will not be mutating like this when we tamp down transmission with mass vaccination.

In conclusion, I and many of my infectious disease colleagues expect the immunity from natural infection or vaccination to COVID-19 to be durable. Let's put discussion of boosters aside and work hard on global vaccine equity and distribution since the pandemic is not over until it is over for us all.

Professor Tim Caulfield stops by the "Making Sense of Science" podcast this month to discuss the infodemic around COVID-19 and how to deal with it.

The "Making Sense of Science" podcast features interviews with leading medical and scientific experts about the latest developments and the big ethical and societal questions they raise. This monthly podcast is hosted by journalist Kira Peikoff, founding editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

Hear the 30-second trailer:

Listen to the whole episode:

.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.