A vaccine for Lyme disease could be coming. But will patients accept it?

Hiking is one of Marci Flory's favorite activities, but her chronic Lyme disease sometimes renders her unable to walk. Biotech companies Pfizer and Valneva are testing a vaccine for Lyme disease in a Phase III clinical trial.

For more than two decades, Marci Flory, a 40-year-old emergency room nurse from Lawrence, Kan., has battled the recurring symptoms of chronic Lyme disease, an illness which she believes began after being bitten by a tick during her teenage years.

Over the years, Flory has been plagued by an array of mysterious ailments, ranging from fatigue to crippling pain in her eyes, joints and neck, and even postural tachycardia syndrome or PoTS, an abnormal increase in heart rate after sitting up or standing. Ten years ago, she began to experience the onset of neurological symptoms which ranged from brain fog to sudden headaches, and strange episodes of leg weakness which would leave her unable to walk.

“Initially doctors thought I had ALS, or less likely, multiple sclerosis,” she says. “But after repeated MRI scans for a year, they concluded I had a rare neurological condition called acute transverse myelitis.”

But Flory was not convinced. After ordering a variety of private blood tests, she discovered she was infected with a range of bacteria in the genus Borrelia that live in the guts of ticks, the infectious agents responsible for Lyme disease.

“It made sense,” she says. “Looking back, I was bitten in high school and misdiagnosed with mononucleosis. This was probably the start, and my immune system kept it under wraps for a while. The Lyme bacteria can burrow into every tissue in the body, go into cyst form and become dormant before reactivating.”

The reason why cases of Lyme disease are increasing is down to changing weather patterns, triggered by climate change, meaning that ticks are now found across a much wider geographic range than ever before.

When these species of bacteria are transmitted to humans, they can attack the nervous system, joints and even internal organs which can lead to serious health complications such as arthritis, meningitis and even heart failure. While Lyme disease can sometimes be successfully treated with antibiotics if spotted early on, not everyone responds to these drugs, and for patients who have developed chronic symptoms, there is no known cure. Flory says she knows of fellow Lyme disease patients who have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars seeking treatments.

Concerningly, statistics show that Lyme and other tick-borne diseases are on the rise. Recently released estimates based on health insurance records suggest that at least 476,000 Americans are diagnosed with Lyme disease every year, and many experts believe the true figure is far higher.

The reason why the numbers are growing is down to changing weather patterns, triggered by climate change, meaning that ticks are now found across a much wider geographic range than ever before. Health insurance data shows that cases of Lyme disease have increased fourfold in rural parts of the U.S. over the last 15 years, and 65 percent in urban regions.

As a result, many scientists who have studied Lyme disease feel that it is paramount to bring some form of protective vaccine to market which can be offered to people living in the most at-risk areas.

“Even the increased awareness for Lyme disease has not stopped the cases,” says Eva Sapi, professor of cellular and molecular biology at the University of New Haven. “Some of these patients are looking for answers for years, running from one doctor to another, so that is obviously a very big cost for our society at so many levels.”

Emerging vaccines – and backlash

But with the rising case numbers, interest has grown among the pharmaceutical industry and research communities. Vienna-based biotech Valneva have partnered with Pfizer to take their vaccine – a seasonal jab which offers protection against the six most common strains of Lyme disease in the northern hemisphere – into a Phase III clinical trial which began in August. Involving 6,000 participants in a number of U.S. states and northern Europe where Lyme disease is endemic, it could lead to a licensed vaccine by 2025, if it proves successful.

“For many years Lyme was considered a small market vaccine,” explains Monica E. Embers, assistant professor of parasitology at Tulane University in New Orleans. “Now we know that this is a much bigger problem, Pfizer has stepped up to invest in preventing this disease and other pharmaceutical companies may as well.”

Despite innovations, patient communities and their representatives remain ambivalent about the idea of a vaccine. Some of this skepticism dates back to the failed LYMErix vaccine which was developed in the late 1990s before being withdrawn from the market.

At the same time, scientists at Yale University are developing a messenger RNA vaccine which aims to train the immune system to respond to tick bites by exposing it to 19 proteins found in tick saliva. Whereas the Valneva vaccine targets the bacteria within ticks, the Yale vaccine attempts to provoke an instant and aggressive immune response at the site of the bite. This causes the tick to fall off and limits the potential for transmitting dangerous infections.

But despite these innovations, patient communities and their representatives remain ambivalent about the idea of a vaccine. Some of this skepticism dates back to the failed LYMErix vaccine which was developed in the late 1990s before being withdrawn from the market in 2002 after concerns were raised that it might induce autoimmune reactions in humans.

While this theory was ultimately disproved, the lingering stigma attached to LYMErix meant that most vaccine manufacturers chose to stay away from the disease for many years, something which Gregory Poland, head of the Mayo Clinic’s Vaccine Research Group in Minnesota, describes as a tragedy.

“Since 2002, we have not had a human Lyme vaccine in the U.S. despite the increasing number of cases,” says Poland. “Pretty much everyone in the field thinks they’re ten times higher than the official numbers, so you’re probably talking at least 400,000 each year. It’s an incredible burden but because of concerns about anti-vax protestors, until very recently, no manufacturer has wanted to touch this.”

Such was the backlash surrounding the failed LYMErix program that scientists have even explored the most creative of workarounds for protecting people in tick-populated regions, without needing to actually vaccinate them. One research program at the University of Tennessee came up with the idea of leaving food pellets containing a vaccine in woodland areas with the idea that rodents would eat the pellets, and the vaccine would then kill Borrelia bacteria within any ticks which subsequently fed on the animals.

Even the Pfizer-Valneva vaccine has been cautiously designed to try and allay any lingering concerns, two decades after LYMErix. “The concept is the same as the original LYMErix vaccine, but it has been made safer by removing regions that had the potential to induce autoimmunity,” says Embers. “There will always be individuals who oppose vaccines, Lyme or otherwise, but it will be a tremendous boost to public health to have the option.”

Vaccine alternatives

Researchers are also considering alternative immunization approaches in case sufficiently large numbers of people choose to reject any Lyme vaccine which gets approved. Researchers at UMass Chan Medical School have developed an artificially generated antibody, administered via an annual injection, which is capable of killing Borrelia bacteria in the guts of ticks before they can get into the human host.

So far animal studies have shown it to be 100 percent effective, while the scientists have completed a Phase I trial in which they tested it for safety on 48 volunteers in Nebraska. Because this approach provides the antibody directly, rather than triggering the human immune system to produce the antibody like a vaccine would, Embers predicts that it could be a viable alternative for the vaccine hesitant as well as providing an option for immunocompromised individuals who cannot produce enough of their own antibodies.

At the same time, many patient groups still raise concerns over the fact that numerous diagnostic tests for Lyme disease have been reported to have a poor accuracy. Without this, they argue that it is difficult to prove whether vaccines or any other form of immunization actually work. “If the disease is not understood enough to create a more accurate test and a universally accepted treatment protocol, particularly for those who weren’t treated promptly, how can we be sure about the efficacy of a vaccine?” says Natasha Metcalf, co-founder of the organization Lyme Disease UK.

Flory points out that there are so many different types of Borrelia bacteria which cause Lyme disease, that the immunizations being developed may only stop a proportion of cases. In addition, she says that chronic Lyme patients often report a whole myriad of co-infections which remain poorly understood and are likely to also be involved in the disease process.

Marci Flory undergoes an infusion in an attempt to treat her Lyme disease symptoms.

Marci Flory

“I would love to see an effective Lyme vaccine but I have my reservations,” she says. “I am infected with four types of Borrelia bacteria, plus many co-infections – Babesia, Bartonella, Erlichiosis, Rickettsia, and Mycoplasma – all from a single Douglas County Kansas tick bite. Lyme never travels alone and the vaccine won’t protect against all the many strains of Borrelia and co-infections.”

Valneva CEO Thomas Lingelbach admits that the Pfizer-Valneva vaccine is not perfect, but predicts that it will still have significant impact if approved.

“We expect the vaccine to have 75 percent plus efficacy,” he says. “There is this legacy around the old Lyme vaccines, but the world is very, very different today. The number of clinical manifestations known to be caused by infection with Lyme Borreliosis has significantly increased, and the understanding around severity has certainly increased.”

Embers agrees that while it will still be important for doctors to monitor for other tick-borne infections which are not necessarily covered by the vaccine, having any clinically approved jab would still represent a major step forward in the fight against the disease.

“I think that any vaccine must be properly vetted, and these companies are performing extensive clinical trials to do just that,” she says. “Lyme is the most common tick-borne disease in the U.S. so the public health impact could be significant. However, clinicians and the general public must remain aware of all of the other tick-borne diseases such as Babesia and Anaplasma, and continue to screen for those when a tick bite is suspected.”

How Excessive Regulation Helped Ignite COVID-19's Rampant Spread

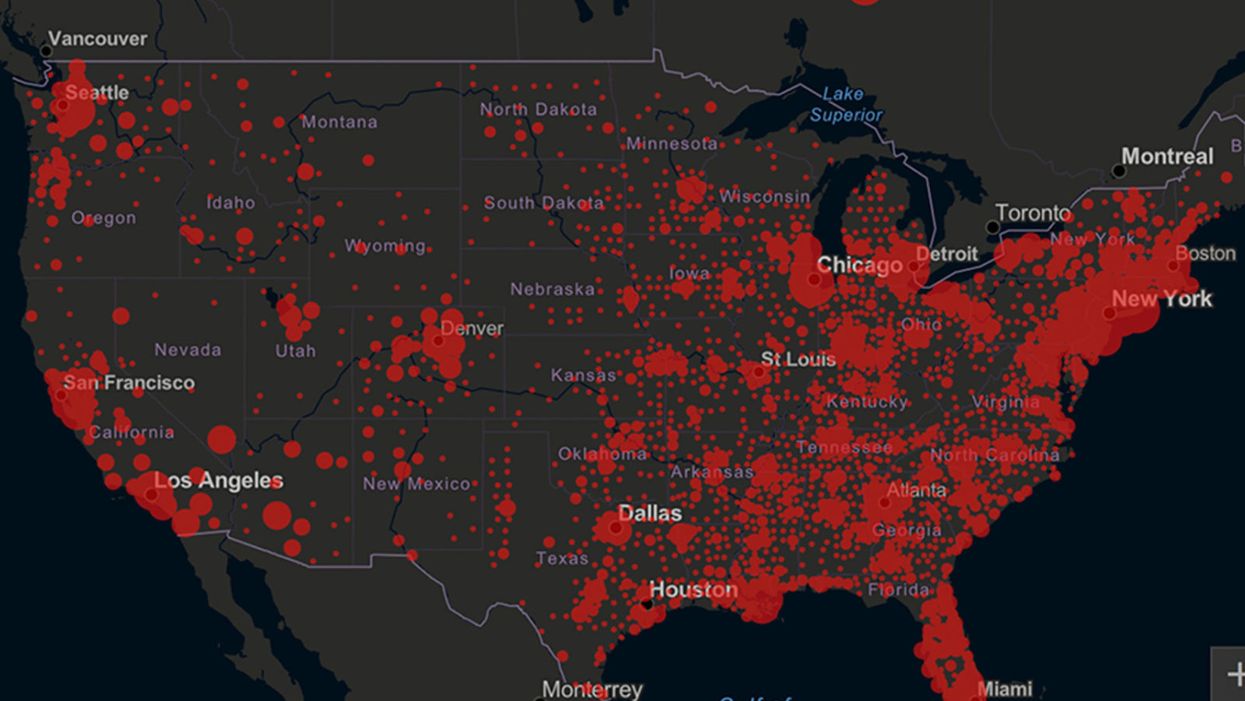

Screenshot of an interactive map of coronavirus cases across the United States, current as of 1:45 p.m. Pacific time on Tuesday, March 31st. Full map accessible at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

When historians of the future look back at the 2020 pandemic, the heroic work of Helen Y. Chu, a flu researcher at the University of Washington, will be worthy of recognition.

Chu's team bravely defied the order and conducted the testing anyway.

In late January, Chu was testing nasal swabs for the Seattle Flu Study to monitor influenza spread when she learned of the first case of COVID-19 in Washington state. She deemed it a pressing public health matter to document if and how the illness was spreading locally, so that early containment efforts could succeed. So she sought regulatory approval to adapt the Flu Study to test for the coronavirus, but the federal government denied the request because the original project was funded to study only influenza.

Aware of the urgency, Chu's team bravely defied the order and conducted the testing anyway. Soon they identified a local case in a teenager without any travel history, followed by others. Still, the government tried to shutter their efforts until the outbreak grew dangerous enough to command attention.

Needless testing delays, prompted by excessive regulatory interference, eliminated any chances of curbing the pandemic at its initial stages. Even after Chu went out on a limb to sound alarms, a heavy-handed bureaucracy crushed the nation's ability to roll out early and widespread testing across the country. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention infamously blundered its own test, while also impeding state and private labs from coming on board, fueling a massive shortage.

The long holdup created "a backlog of testing that needed to be done," says Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease specialist who is a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security.

In a public health crisis, "the ideal situation" would allow the government's test to be "supplanted by private laboratories" without such "a lag in that transition," Adalja says. Only after the eventual release of CDC's test could private industry "begin in earnest" to develop its own versions under the Food and Drug Administration's emergency use authorization.

In a statement, CDC acknowledged that "this process has not gone as smoothly as we would have liked, but there is currently no backlog for testing at CDC."

Now, universities and corporations are in a race against time, playing catch up as the virus continues its relentless spread, also afflicting many health care workers on the front lines.

"Home-testing accessibility is key to preventing further spread of the COVID-19 pandemic."

Hospitals are attempting to add the novel coronavirus to the testing panel of their existent diagnostic machines, which would reduce the results processing time from 48 hours to as little as four hours. Meanwhile, at least four companies announced plans to deliver at-home collection tests to help meet the demand – before a startling injunction by the FDA halted their plans.

Everlywell, an Austin, Texas-based digital health company, had been set to launch online sales of at-home collection kits directly to consumers last week. Scaling up in a matter of days to an initial supply of 30,000 tests, Everlywell collaborated with multiple laboratories where consumers could ship their nasal swab samples overnight, projecting capacity to screen a quarter-million individuals on a weekly basis, says Frank Ong, chief medical and scientific officer.

Secure digital results would have been available online within 48 hours of a sample's arrival at the lab, as well as a telehealth consultation with an independent, board-certified doctor if someone tested positive, for an inclusive $135 cost. The test has a less than 3 percent false-negative rate, Ong says, and in the event of an inadequate self-swab, the lab would not report a conclusive finding. "Home-testing accessibility," he says, "is key to preventing further spread of the COVID-19 pandemic."

But on March 20, the FDA announced restrictions on home collection tests due to concerns about accuracy. The agency did note "the public health value in expanding the availability of COVID-19 testing through safe and accurate tests that may include home collection," while adding that "we are actively working with test developers in this space."

After the restrictions were announced, Everlywell decided to allocate its initial supply of COVID-19 collection kits to hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and other qualifying health care companies that can commit to no-cost screening of frontline workers and high-risk symptomatic patients. For now, no consumers can order a home-collection test.

"Losing two months is close to disastrous, and that's what we did."

Currently, the U.S. has ramped up to testing an estimated 100,000 people a day, according to Stat News. But 150,000 or more Americans should be tested every day, says Ashish Jha, professor and director of the Harvard Global Health Institute. Due to the dearth of tests, many sick people who suspect they are infected still cannot get confirmation unless they need to be hospitalized.

To give a concrete sense of how far behind we are in testing, consider Palm Beach County, Fla. The state's only drive-thru test center just opened there, requiring an appointment. The center aims to test 750 people per day, but more than 330,000 people have already called to try to book a slot.

"This is such a rapidly moving infection that losing a few days is bad, and losing a couple of weeks is terrible," says Jha, a practicing general internist. "Losing two months is close to disastrous, and that's what we did."

At this point, it will take a long time to fully ramp up. "We are blindfolded," he adds, "and I'd like to take the blindfolds off so we can fight this battle with our eyes wide open."

Better late than never: Yesterday, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said in a statement that the agency has worked with more than 230 test developers and has approved 20 tests since January. An especially notable one was authorized last Friday – 67 days since the country's first known case in Washington state. It's a rapid point-of-care test from medical-device firm Abbott that provides positive results in five minutes and negative results in 13 minutes. Abbott will send 50,000 tests a day to urgent care settings. The first tests are expected to ship tomorrow.

Your Privacy vs. the Public's Health: High-Tech Tracking to Fight COVID-19 Evokes Orwell

Governments around the world are using technology to track their citizens to contain COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed public health and personal privacy on a collision course, as smartphone technology has completely rewritten the book on contact tracing.

It's not surprising that an autocratic regime like China would adopt such measures, but democracies such as Israel have taken a similar path.

The gold standard – patient interviews and detective work – had been in place for more than a century. It's been all but replaced by GPS data in smartphones, which allows contact tracing to occur not only virtually in real time, but with vastly more precision.

China has gone the furthest in using such tech to monitor and prevent the spread of the coronavirus. It developed an app called Health Code to determine which of its citizens are infected or at risk of becoming infected. It has assigned each individual a color code – red, yellow or green – and restricts their movement depending on their assignment. It has also leveraged its millions of public video cameras in conjunction with facial recognition tech to identify people in public who are not wearing masks.

It's not surprising that an autocratic regime like China would adopt such measures, but democracies such as Israel have taken a similar path. The national security agency Shin Bet this week began analyzing all personal cellphone data under emergency measures approved by the government. It texts individuals when it's determined they had been in contact with someone who had the coronavirus. In Spain and China, police have sent drones aloft searching for people violating stay-at-home orders. Commands to disperse can be issued through audio systems built into the aircraft. In the U.S., efforts are underway to lift federal restrictions on drones so that police can use them to prevent people from gathering.

The chief executive of a drone manufacturer in the U.S. aptly summed up the situation in an interview with the Financial Times: "It seems a little Orwellian, but this could save lives."

Epidemics and how they're surveilled often pose thorny dilemmas, according to Craig Klugman, a bioethicist and professor of health sciences at DePaul University in Chicago. "There's always a moral issue to contact tracing," he said, adding that the issue doesn't change by nation, only in the way it's resolved.

"Once certain privacy barriers have been breached, it can be difficult to roll them back again."

In China, there's little to no expectation for privacy, so their decision to take the most extreme measures makes sense to Klugman. "In China, the community comes first. In the U.S., individual rights come first," he said.

As the U.S. has scrambled to develop testing kits and manufacture ventilators to identify potential patients and treat them, individual rights have mostly not received any scrutiny. However, that could change in the coming weeks.

The American approach is also leaning toward using smartphone apps, but in a way that may preserve the privacy of users. Researchers at MIT have released a prototype known as Private Kit: Safe Paths. Patients diagnosed with the coronavirus can use the app to disclose their location trail for the prior 28 days to other users without releasing their specific identity. They also have the option of sharing the data with public health officials. But such an app would only be effective if there is a significant number of users.

Singapore is offering a similar app to its citizens known as TraceTogether, which uses both GPS and Bluetooth pings among users to trace potential encounters. It's being offered on a voluntary basis.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, the leading nonprofit organization defending civil liberties in the digital world, said it is monitoring how these apps are developed and deployed. "Governments around the world are demanding new dragnet location surveillance powers to contain the COVID-19 outbreak," it said in a statement. "But before the public allows their governments to implement such systems, governments must explain to the public how these systems would be effective in stopping the spread of COVID-19. There's no questioning the need for far-reaching public health measures to meet this urgent challenge, but those measures must be scientifically rigorous, and based on the expertise of public health professionals."

Andrew Geronimo, director of the intellectual property venture clinic at the Case Western University School of Law, said that the U.S. government is currently in talks with Facebook, Google and other tech companies about using deidentified location data from smartphones to better monitor the progress of the outbreak. He was hesitant to endorse such a step.

"These companies may say that all of this data is anonymized," he said, "but studies have shown that it is difficult to fully anonymize data sets that contain so much information about us."

Beyond the technical issues, social attitudes may mount another challenge. Epic events such as 9/11 tend to loosen vigilance toward protecting privacy, according to Klugman and Geronimo. And as more people are sickened and hospitalized in the U.S. with COVID-19, Klugman believes more Americans will be willing to allow themselves to be tracked. "If that happens, there needs to be a time limitation," he said.

However, even if time limits are put in place, Geronimo believes it would lead to an even greater rollback of privacy during the next crisis.

"Once certain privacy barriers have been breached, it can be difficult to roll them back again," he warned. "And the prior incidents could always be used as a precedent – or as proof of concept."