Meet the Scientists on the Frontlines of Protecting Humanity from a Man-Made Pathogen

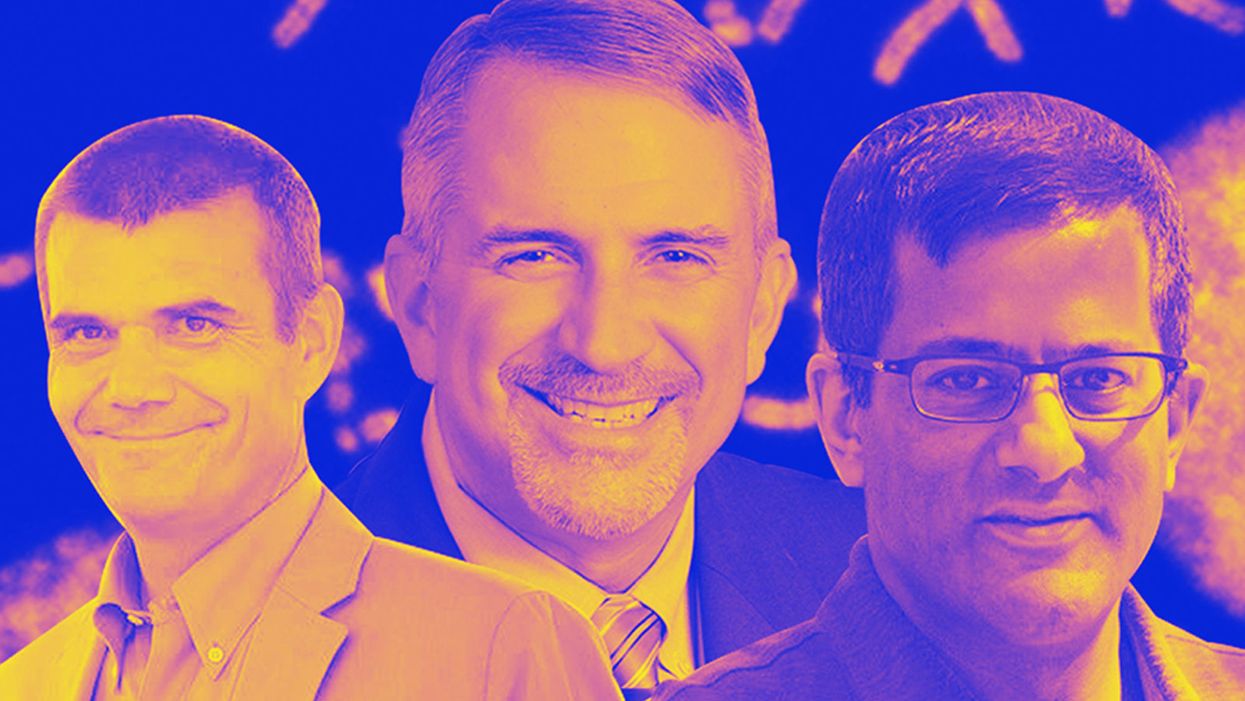

From left: Jean Peccoud, Randall Murch, and Neeraj Rao.

Jean Peccoud wasn't expecting an email from the FBI. He definitely wasn't expecting the agency to invite him to a meeting. "My reaction was, 'What did I do wrong to be on the FBI watch list?'" he recalls.

You use those blueprints for white-hat research—which is, indeed, why the open blueprints exist—or you can do the same for a black-hat attack.

He didn't know what the feds could possibly want from him. "I was mostly scared at this point," he says. "I was deeply disturbed by the whole thing."

But he decided to go anyway, and when he traveled to San Francisco for the 2008 gathering, the reason for the e-vite became clear: The FBI was reaching out to researchers like him—scientists interested in synthetic biology—in anticipation of the potential nefarious uses of this technology. "The whole purpose of the meeting was, 'Let's start talking to each other before we actually need to talk to each other,'" says Peccoud, now a professor of chemical and biological engineering at Colorado State University. "'And let's make sure next time you get an email from the FBI, you don't freak out."

Synthetic biology—which Peccoud defines as "the application of engineering methods to biological systems"—holds great power, and with that (as always) comes great responsibility. When you can synthesize genetic material in a lab, you can create new ways of diagnosing and treating people, and even new food ingredients. But you can also "print" the genetic sequence of a virus or virulent bacterium.

And while it's not easy, it's also not as hard as it could be, in part because dangerous sequences have publicly available blueprints. You use those blueprints for white-hat research—which is, indeed, why the open blueprints exist—or you can do the same for a black-hat attack. You could synthesize a dangerous pathogen's code on purpose, or you could unwittingly do so because someone tampered with your digital instructions. Ordering synthetic genes for viral sequences, says Peccoud, would likely be more difficult today than it was a decade ago.

"There is more awareness of the industry, and they are taking this more seriously," he says. "There is no specific regulation, though."

Trying to lock down the interconnected machines that enable synthetic biology, secure its lab processes, and keep dangerous pathogens out of the hands of bad actors is part of a relatively new field: cyberbiosecurity, whose name Peccoud and colleagues introduced in a 2018 paper.

Biological threats feel especially acute right now, during the ongoing pandemic. COVID-19 is a natural pathogen -- not one engineered in a lab. But future outbreaks could start from a bug nature didn't build, if the wrong people get ahold of the right genetic sequences, and put them in the right sequence. Securing the equipment and processes that make synthetic biology possible -- so that doesn't happen -- is part of why the field of cyberbiosecurity was born.

The Origin Story

It is perhaps no coincidence that the FBI pinged Peccoud when it did: soon after a journalist ordered a sequence of smallpox DNA and wrote, for The Guardian, about how easy it was. "That was not good press for anybody," says Peccoud. Previously, in 2002, the Pentagon had funded SUNY Stonybrook researchers to try something similar: They ordered bits of polio DNA piecemeal and, over the course of three years, strung them together.

Although many years have passed since those early gotchas, the current patchwork of regulations still wouldn't necessarily prevent someone from pulling similar tricks now, and the technological systems that synthetic biology runs on are more intertwined — and so perhaps more hackable — than ever. Researchers like Peccoud are working to bring awareness to those potential problems, to promote accountability, and to provide early-detection tools that would catch the whiff of a rotten act before it became one.

Peccoud notes that if someone wants to get access to a specific pathogen, it is probably easier to collect it from the environment or take it from a biodefense lab than to whip it up synthetically. "However, people could use genetic databases to design a system that combines different genes in a way that would make them dangerous together without each of the components being dangerous on its own," he says. "This would be much more difficult to detect."

After his meeting with the FBI, Peccoud grew more interested in these sorts of security questions. So he was paying attention when, in 2010, the Department of Health and Human Services — now helping manage the response to COVID-19 — created guidance for how to screen synthetic biology orders, to make sure suppliers didn't accidentally send bad actors the sequences that make up bad genomes.

Guidance is nice, Peccoud thought, but it's just words. He wanted to turn those words into action: into a computer program. "I didn't know if it was something you can run on a desktop or if you need a supercomputer to run it," he says. So, one summer, he tasked a team of student researchers with poring over the sentences and turning them into scripts. "I let the FBI know," he says, having both learned his lesson and wanting to get in on the game.

Peccoud later joined forces with Randall Murch, a former FBI agent and current Virginia Tech professor, and a team of colleagues from both Virginia Tech and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, on a prototype project for the Department of Defense. They went into a lab at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln and assessed all its cyberbio-vulnerabilities. The lab develops and produces prototype vaccines, therapeutics, and prophylactic components — exactly the kind of place that you always, and especially right now, want to keep secure.

"We were creating wiki of all these nasty things."

The team found dozens of Achilles' heels, and put them in a private report. Not long after that project, the two and their colleagues wrote the paper that first used the term "cyberbiosecurity." A second paper, led by Murch, came out five months later and provided a proposed definition and more comprehensive perspective on cyberbiosecurity. But although it's now a buzzword, it's the definition, not the jargon, that matters. "Frankly, I don't really care if they call it cyberbiosecurity," says Murch. Call it what you want: Just pay attention to its tenets.

A Database of Scary Sequences

Peccoud and Murch, of course, aren't the only ones working to screen sequences and secure devices. At the nonprofit Battelle Memorial Institute in Columbus, Ohio, for instance, scientists are working on solutions that balance the openness inherent to science and the closure that can stop bad stuff. "There's a challenge there that you want to enable research but you want to make sure that what people are ordering is safe," says the organization's Neeraj Rao.

Rao can't talk about the work Battelle does for the spy agency IARPA, the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity, on a project called Fun GCAT, which aims to use computational tools to deep-screen gene-sequence orders to see if they pose a threat. It can, though, talk about a twin-type internal project: ThreatSEQ (pronounced, of course, "threat seek").

The project started when "a government customer" (as usual, no one will say which) asked Battelle to curate a list of dangerous toxins and pathogens, and their genetic sequences. The researchers even started tagging sequences according to their function — like whether a particular sequence is involved in a germ's virulence or toxicity. That helps if someone is trying to use synthetic biology not to gin up a yawn-inducing old bug but to engineer a totally new one. "How do you essentially predict what the function of a novel sequence is?" says Rao. You look at what other, similar bits of code do.

"We were creating wiki of all these nasty things," says Rao. As they were working, they realized that DNA manufacturers could potentially scan in sequences that people ordered, run them against the database, and see if anything scary matched up. Kind of like that plagiarism software your college professors used.

Battelle began offering their screening capability, as ThreatSEQ. When customers -- like, currently, Twist Bioscience -- throw their sequences in, and get a report back, the manufacturers make the final decision about whether to fulfill a flagged order — whether, in the analogy, to give an F for plagiarism. After all, legitimate researchers do legitimately need to have DNA from legitimately bad organisms.

"Maybe it's the CDC," says Rao. "If things check out, oftentimes [the manufacturers] will fulfill the order." If it's your aggrieved uncle seeking the virulent pathogen, maybe not. But ultimately, no one is stopping the manufacturers from doing so.

Beyond that kind of tampering, though, cyberbiosecurity also includes keeping a lockdown on the machines that make the genetic sequences. "Somebody now doesn't need physical access to infrastructure to tamper with it," says Rao. So it needs the same cyber protections as other internet-connected devices.

Scientists are also now using DNA to store data — encoding information in its bases, rather than into a hard drive. To download the data, you sequence the DNA and read it back into a computer. But if you think like a bad guy, you'd realize that a bad guy could then, for instance, insert a computer virus into the genetic code, and when the researcher went to nab her data, her desktop would crash or infect the others on the network.

Something like that actually happened in 2017 at the USENIX security symposium, an annual programming conference: Researchers from the University of Washington encoded malware into DNA, and when the gene sequencer assembled the DNA, it corrupted the sequencer's software, then the computer that controlled it.

"This vulnerability could be just the opening an adversary needs to compromise an organization's systems," Inspirion Biosciences' J. Craig Reed and Nicolas Dunaway wrote in a paper for Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, included in an e-book that Murch edited called Mapping the Cyberbiosecurity Enterprise.

Where We Go From Here

So what to do about all this? That's hard to say, in part because we don't know how big a current problem any of it poses. As noted in Mapping the Cyberbiosecurity Enterprise, "Information about private sector infrastructure vulnerabilities or data breaches is protected from public release by the Protected Critical Infrastructure Information (PCII) Program," if the privateers share the information with the government. "Government sector vulnerabilities or data breaches," meanwhile, "are rarely shared with the public."

"What I think is encouraging right now is the fact that we're even having this discussion."

The regulations that could rein in problems aren't as robust as many would like them to be, and much good behavior is technically voluntary — although guidelines and best practices do exist from organizations like the International Gene Synthesis Consortium and the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Rao thinks it would be smart if grant-giving agencies like the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation required any scientists who took their money to work with manufacturing companies that screen sequences. But he also still thinks we're on our way to being ahead of the curve, in terms of preventing print-your-own bioproblems: "What I think is encouraging right now is the fact that we're even having this discussion," says Rao.

Peccoud, for his part, has worked to keep such conversations going, including by doing training for the FBI and planning a workshop for students in which they imagine and work to guard against the malicious use of their research. But actually, Peccoud believes that human error, flawed lab processes, and mislabeled samples might be bigger threats than the outside ones. "Way too often, I think that people think of security as, 'Oh, there is a bad guy going after me,' and the main thing you should be worried about is yourself and errors," he says.

Murch thinks we're only at the beginning of understanding where our weak points are, and how many times they've been bruised. Decreasing those contusions, though, won't just take more secure systems. "The answer won't be technical only," he says. It'll be social, political, policy-related, and economic — a cultural revolution all its own.

The Nose Knows: Dogs Are Being Trained to Detect the Coronavirus

Security workers walk with detection dogs in an airport terminal.

Asher is eccentric and inquisitive. He loves an audience, likes keeping busy, and howls to be let through doors. He is a six-year-old working Cocker Spaniel, who, with five other furry colleagues, has now been trained to sniff body odor samples from humans to detect COVID-19 infections.

As the Delta variant and other new versions of the SARS-CoV-2 virus emerge, public health agencies are once again recommending masking while employers contemplate mandatory vaccination. While PCR tests remain the "gold standard" of COVID-19 tests, they can take hours to flag infections. To accelerate the process, scientists are turning to a new testing tool: sniffer dogs.

At the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), researchers deployed Asher and five other trained dogs to test sock samples from 200 asymptomatic, infected individuals and 200 healthy individuals. In May, they published the findings of the yearlong study in a preprint, concluding that dogs could identify COVID-19 infections with a high degree of accuracy – they could correctly identify a COVID-positive sample up to 94% of the time and a negative sample up to 92% of the time. The paper has yet to be peer-reviewed.

"Dogs can screen lots of people very quickly – 300 people per dog per hour. This means they could be used in places like airports or public venues like stadiums and maybe even workplaces," says James Logan, who heads the Department of Disease Control at LSHTM, adding that canines can also detect variants of SARS-CoV-2. "We included samples from two variants and the dogs could still detect them."

Detection dogs have been one of the most reliable biosensors for identifying the odor of human disease. According to Gemma Butlin, a spokesperson of Medical Detection Dogs, the UK-based charity that trained canines for the LSHTM study, the olfactory capabilities of dogs have been deployed to detect malaria, Parkinson's disease, different types of cancers, as well as pseudomonas, a type of bacteria known to cause infections in blood, lungs, eyes, and other parts of the human body.

COVID-19 has a distinctive smell — a result of chemicals known as volatile organic compounds released by infected body cells, which give off an odor "fingerprint."

"It's estimated that the percentage of a dog's brain devoted to analyzing odors is 40 times larger than that of a human," says Butlin. "Humans have around 5 million scent receptors dedicated to smell. Dogs have 350 million and can detect odors at parts per trillion. To put this into context, a dog can detect a teaspoon of sugar in a million gallons of water: two Olympic-sized pools full."

According to LSHTM scientists, COVID-19 has a distinctive smell — a result of chemicals known as volatile organic compounds released by infected body cells, which give off an odor "fingerprint." Other studies, too, have revealed that the SARS-CoV-2 virus has a distinct olfactory signature, detectable in the urine, saliva, and sweat of infected individuals. Humans can't smell the disease in these fluids, but dogs can.

"Our research shows that the smell associated with COVID-19 is at least partly due to small and volatile chemicals that are produced by the virus growing in the body or the immune response to the virus or both," said Steve Lindsay, a public health entomologist at Durham University, whose team collaborated with LSHTM for the study. He added, "There is also a further possibility that dogs can actually smell the virus, which is incredible given how small viruses are."

In April this year, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and collaborators published a similar study in the scientific journal PLOS One, revealing that detection dogs could successfully discriminate between urine samples of infected and uninfected individuals. The accuracy rate of canines in this study was 96%. Similarly, last December, French scientists found that dogs were 76-100% effective at identifying individuals with COVID-19 when presented with sweat samples.

Grandjean Dominique, a professor at France's National Veterinary School of Alfort, who led the French study, said that the researchers used two types of dogs — search and rescue dogs, as they can sniff sweat, and explosive detection dogs, because they're often used at airports to find bomb ingredients. Dogs may very well be as good as PCR tests, said Dominique, but the goal, he added, is not to replace these tests with canines.

In France, the government gave the green light to train hundreds of disease detection dogs and deploy them in airports. "They will act as mass pre-test, and only people who are positive will undergo a PCR test to check their level of infection and the kind of variant," says Dominique. He thinks the dogs will be able to decrease the amount of PCR testing and potentially save money.

Since the accuracy rate for bio-detection dogs is fairly high, scientists think they could prove to be a quick diagnosis and mass screening tool, especially at ports, airports, train stations, stadiums, and public gatherings. Countries like Finland, Thailand, UAE, Italy, Chile, India, Australia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, and Mexico are already training and deploying canines for COVID-19 detection. The dogs are trained to sniff the area around a person, and if they find the odor of COVID-19 they will sit or stand back from an individual as a signal that they've identified an infection.

While bio-detection dogs seem promising for cheap, large-volume screening, many of the studies that have been performed to date have been small and in controlled environments. The big question is whether this approach work on people in crowded airports, not just samples of shirts and socks in a lab.

"The next step is 'real world' testing where they [canines] are placed in airports to screen people and see how they perform," says Anna Durbin, professor of international health at the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. "Testing in real airports with lots of passengers and competing scents will need to be done."

According to Butlin of Medical Detection Dogs, scalability could be a challenge. However, scientists don't intend to have a dog in every waiting room, detecting COVID-19 or other diseases, she said.

"Dogs are the most reliable bio sensors on the planet and they have proven time and time again that they can detect diseases as accurately, if not more so, than current technological diagnostics," said Butlin. "We are learning from them all the time and what their noses know will one day enable the creation an 'E-nose' that does the same job – imagine a day when your mobile phone can tell you that you are unwell."

The Voice Behind Some of Your Favorite Cartoon Characters Helped Create the Artificial Heart

This Jarvik-7 artificial heart was used in the first bridge operation in 1985 meant to replace a failing heart while the patient waited for a donor organ.

In June, a team of surgeons at Duke University Hospital implanted the latest model of an artificial heart in a 39-year-old man with severe heart failure, a condition in which the heart doesn't pump properly. The man's mechanical heart, made by French company Carmat, is a new generation artificial heart and the first of its kind to be transplanted in the United States. It connects to a portable external power supply and is designed to keep the patient alive until a replacement organ becomes available.

Many patients die while waiting for a heart transplant, but artificial hearts can bridge the gap. Though not a permanent solution for heart failure, artificial hearts have saved countless lives since their first implantation in 1982.

What might surprise you is that the origin of the artificial heart dates back decades before, when an inventive television actor teamed up with a famous doctor to design and patent the first such device.

A man of many talents

Paul Winchell was an entertainer in the 1950s and 60s, rising to fame as a ventriloquist and guest-starring as an actor on programs like "The Ed Sullivan Show" and "Perry Mason." When children's animation boomed in the 1960s, Winchell made a name for himself as a voice actor on shows like "The Smurfs," "Winnie the Pooh," and "The Jetsons." He eventually became famous for originating the voices of Tigger from "Winnie the Pooh" and Gargamel from "The Smurfs," among many others.

But Winchell wasn't just an entertainer: He also had a quiet passion for science and medicine. Between television gigs, Winchell busied himself working as a medical hypnotist and acupuncturist, treating the same Hollywood stars he performed alongside. When he wasn't doing that, Winchell threw himself into engineering and design, building not only the ventriloquism dummies he used on his television appearances but a host of products he'd dreamed up himself. Winchell spent hours tinkering with his own inventions, such as a set of battery-powered gloves and something called a "flameless lighter." Over the course of his life, Winchell designed and patented more than 30 of these products – mostly novelties, but also serious medical devices, such as a portable blood plasma defroster.

| Ventriloquist Paul Winchell with Jerry Mahoney, his dummy, in 1951 |

A meeting of the minds

In the early 1950s, Winchell appeared on a variety show called the "Arthur Murray Dance Party" and faced off in a dance competition with the legendary Ricardo Montalban (Winchell won). At a cast party for the show later that same night, Winchell met Dr. Henry Heimlich – the same doctor who would later become famous for inventing the Heimlich maneuver, who was married to Murray's daughter. The two hit it off immediately, bonding over their shared interest in medicine. Before long, Heimlich invited Winchell to come observe him in the operating room at the hospital where he worked. Winchell jumped at the opportunity, and not long after he became a frequent guest in Heimlich's surgical theatre, fascinated by the mechanics of the human body.

One day while Winchell was observing at the hospital, he witnessed a patient die on the operating table after undergoing open-heart surgery. He was suddenly struck with an idea: If there was some way doctors could keep blood pumping temporarily throughout the body during surgery, patients who underwent risky operations like open-heart surgery might have a better chance of survival. Winchell rushed to Heimlich with the idea – and Heimlich agreed to advise Winchell and look over any design drafts he came up with. So Winchell went to work.

Winchell's heart

As it turned out, building ventriloquism dummies wasn't that different from building an artificial heart, Winchell noted later in his autobiography – the shifting valves and chambers of the mechanical heart were similar to the moving eyes and opening mouths of his puppets. After each design, Winchell would go back to Heimlich and the two would confer, making adjustments along the way to.

By 1956, Winchell had perfected his design: The "heart" consisted of a bag that could be placed inside the human body, connected to a battery-powered motor outside of the body. The motor enabled the bag to pump blood throughout the body, similar to a real human heart. Winchell received a patent for the design in 1963.

At the time, Winchell never quite got the credit he deserved. Years later, researchers at the University of Utah, working on their own artificial heart, came across Winchell's patent and got in touch with Winchell to compare notes. Winchell ended up donating his patent to the team, which included Dr. Richard Jarvik. Jarvik expanded on Winchell's design and created the Jarvik-7 – the world's first artificial heart to be successfully implanted in a human being in 1982.

The Jarvik-7 has since been replaced with newer, more efficient models made up of different synthetic materials, allowing patients to live for longer stretches without the heart clogging or breaking down. With each new generation of hearts, heart failure patients have been able to live relatively normal lives for longer periods of time and with fewer complications than before – and it never would have been possible without the unsung genius of a puppeteer and his love of science.