The Inside Story of Two Young Scientists Who Helped Make Moderna's Covid Vaccine Possible

Scientists Jason Schrum and Kerry Benenato solved crucial challenges in mRNA vaccine development.

In early 2020, Moderna Inc. was a barely-known biotechnology company with an unproven approach. It wanted to produce messenger RNA molecules to carry instructions into the body, teaching it to ward off disease. Experts doubted the Boston-based company would meet success.

Today, Moderna is a pharmaceutical power thanks to its success developing an effective Covid-19 vaccine. The company is worth $124 billion, more than giants including GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi, and evidence has emerged that Moderna's shots are more protective than those produced by Pfizer-BioNTech and other vaccine makers. Pressure is building on the company to deliver more of its doses to people around the world, especially in poorer countries, and Moderna is working on vaccines against other pathogens, including Zika, influenza and cytomegalovirus.

But Moderna encountered such difficulties over the course of its eleven-year history that some executives worried it wouldn't survive. Two unlikely scientists helped save the company. Their breakthroughs paved the way for Moderna's Covid-19 shots but their work has never been publicized nor have their contributions been properly appreciated.

Derrick Rossi, a scientist at MIT, and Noubar Afeyan, a Cambridge-based investor, launched Moderna in September 2010. Their idea was to create mRNA molecules capable of delivering instructions to the body's cells, directing them to make proteins to heal ailments and cure disease. Need a statin, immunosuppressive, or other drug or vaccine? Just use mRNA to send a message to the body's cells to produce it. Rossi and Afeyan were convinced injecting mRNA into the body could turn it into its own laboratory, generating specific medications or vaccines as needed.

At the time, the notion that one might be able to teach the body to make proteins bordered on heresy. Everyone knew mRNA was unstable and set off the body's immune system on its way into cells. But in the late 2000's, two scientists at the University of Pennsylvania, Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, had figured out how to modify mRNA's chemical building blocks so the molecule could escape the notice of the immune system and enter the cell. Rossi and Afeyan couldn't convince the University of Pennsylvania to license Karikó and Weissman's patent, however, stymying Moderna's early ambitions. At the same time, the Penn scientists' technique seemed more applicable to an academic lab than a biotech company that needed to produce drugs or shots consistently and in bulk. Rossi and Afeyan's new company needed their own solution to help mRNA evade the body's defenses.

Some of Moderna's founders doubted Schrum could find success and they worried if their venture was doomed from the start.

The Scientist Who Modified mRNA: Jason Schrum

In 2010, Afeyan's firm subleased laboratory space in the basement of another Cambridge biotech company to begin scientific work. Afeyan chose a young scientist on his staff, Jason Schrum, to be Moderna's first employee, charging him with getting mRNA into cells without relying on Karikó and Weissman's solutions.

Schrum seemed well suited for the task. Months earlier, he had received a PhD in biological chemistry at Harvard University, where he had focused on nucleotide chemistry. Schrum even had the look of someone who might do big things. The baby-faced twenty-eight-year-old favored a relaxed, start-up look: khakis, button-downs, and Converse All-Stars.

Schrum felt immediate strain, however. He hadn't told anyone, but he was dealing with intense pain in his hands and joints, a condition that later would be diagnosed as degenerative arthritis. Soon Schrum couldn't bend two fingers on his left hand, making lab work difficult. He joined a drug trial, but the medicine proved useless. Schrum tried corticosteroid injections and anti-inflammatory drugs, but his left hand ached, restricting his experiments.

"It just wasn't useful," Schrum says, referring to his tender hand.*

He persisted, nonetheless. Each day in the fall of 2010, Schrum walked through double air-locked doors into a sterile "clean room" before entering a basement laboratory, in the bowels of an office in Cambridge's Kendall Square neighborhood, where he worked deep into the night. Schrum searched for potential modifications of mRNA nucleosides, hoping they might enable the molecule to produce proteins. Like all such rooms, there were no windows, so Schrum had to check a clock to know if it was day or night. A colleague came to visit once in a while, but most of the time, Schrum was alone.

Some of Moderna's founders doubted Schrum could find success and they worried if their venture was doomed from the start. An established MIT scientist turned down a job with the start-up to join pharmaceutical giant Novartis, dubious of Moderna's approach. Colleagues wondered if mRNA could produce proteins, at least on a consistent basis.

As Schrum began testing the modifications in January 2011, he made an unexpected discovery. Karikó and Weissman saw that by turned one of the building blocks for mRNA, a ribonucleoside called uridine, into a slightly different form called pseudouridine, the cell's immune system ignored the mRNA and the molecule avoided an immune response. After a series of experiments in the basement lab, Schrum discovered that a variant of pseudouridine called N1- methyl-pseudouridine did an even better job reducing the cell's innate immune response. Schrum's nucleoside switch enabled even higher protein production than Karikó and Weissman had generated, and Schrum's mRNAs lasted longer than either unmodified molecules or the modified mRNA the Penn academics had used, startling the young researcher. Working alone in a dreary basement and through intense pain, he had actually improved on the Penn professors' work.

Years later, Karikó and Weissman who would win acclaim. In September 2021, the scientists were awarded the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award. Some predict they eventually will win a Nobel prize. But it would be Schrum's innovation that would form the backbone of both Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech's Covid-19 vaccine, not the chemical modifications that Karikó and Weissman developed. For Schrum, necessity had truly been the mother of invention.

The Scientist Who Solved Delivery: Kerry Benenato

For several years, Moderna would make slow progress developing drugs to treat various diseases. Eventually, the company decided that mRNA was likely better suited for vaccines. By 2017, Moderna and the National Institutes of Health were discussing working together to develop mRNA–based vaccines, a partnership that buoyed Moderna's executives. There remained a huge obstacle in Moderna's way, however. It was up to Kerry Benenato to find a solution.

Benenato received an early hint of the hurdle in front of her three years earlier, when the organic chemist was first hired. When a colleague gave her a company tour, she was introduced to Moderna's chief scientific officer, Joseph Bolen, who seemed unusually excited to meet her.

"Oh, great!" Bolen said with a smile. "She's the one who's gonna solve delivery."

Bolen gave a hearty laugh and walked away, but Benenato detected seriousness in his quip.

Solve delivery?

It was a lot to expect from a 37-year-old scientist already dealing with insecurities and self-doubt. Benenato was an accomplished researcher who most recently had worked at AstraZeneca after completing post-doctoral studies at Harvard University. Despite her impressive credentials, Benenato battled a lack of confidence that sometimes got in her way. Performance reviews from past employers had been positive, but they usually produced similar critiques: Be more vocal. Do a better job advocating for your ideas. Give us more, Kerry.

Benenato was petite and soft-spoken. She sometimes stuttered or relied on "ums" and "ahs" when she became nervous, especially in front of groups, part of why she sometimes didn't feel comfortable speaking up.

"I'm an introvert," she says. "Self-confidence is something that's always been an issue."

To Benenato, Moderna's vaccine approach seemed promising—the team was packaging mRNAs in microscopic fatty-acid compounds called lipid nanoparticles, or LNPs, that protected the molecules on their way into cells. Moderna's shots should have been producing ample and long-lasting proteins. But the company's scientists were alarmed—they were injecting shots deep into the muscle of mice, but their immune systems were mounting spirited responses to the foreign components of the LNPs, which had been developed by a Canadian company.

This toxicity was a huge issue: A vaccine or drug that caused sharp pain and awful fevers wasn't going to prove very popular. The Moderna team was in a bind: Its mRNA had to be wrapped in the fatty nanoparticles to have a chance at producing plentiful proteins, but the body wasn't tolerating the microscopic encasements, especially upon repeated dosing.

The company's scientists had done everything they could to try to make the molecule's swathing material disappear soon after entering the cells, in order to avoid the unfortunate side effects, such as chills and headaches, but they weren't making headway. Frustration mounted. Somehow, the researchers had to find a way to get the encasements—made of little balls of fat, cholesterol, and other substances—to deliver their payload mRNA and then quickly vanish, like a parent dropping a teenager off at a party, to avoid setting off the immune system in unpleasant ways, even as the RNA and the proteins the molecule created stuck around.

Benenato wasn't entirely shocked by the challenges Moderna was facing. One of the reasons she had joined the upstart company was to help develop its delivery technology. She just didn't realize how pressing the issue was, or how stymied the researchers had become. Benenato also didn't know that Moderna board members were among those most discouraged by the delivery issue. In meetings, some of them pointed out that pharmaceutical giants like Roche Holding and Novartis had worked on similar issues and hadn't managed to develop lipid nanoparticles that were both effective and well tolerated by the body. Why would Moderna have any more luck?

Stephen Hoge insisted the company could yet find a solution.

"There's no way the only innovations in LNP are going to come from some academics and a small Canadian company," insisted Hoge, who had convinced the executives that hiring Benenato might help deliver an answer.

Benenato realized that while Moderna might have been a hot Boston-area start- up, it wasn't set up to do the chemistry necessary to solve their LNP problem. Much of its equipment was old or secondhand, and it was the kind used to tinker with mRNAs, not lipids.

"It was scary," she says.

When Benenato saw the company had a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer, which allows chemists to see the molecular structure of material, she let out a sigh of relief. Then Benenato inspected the machine and realized it was a jalopy. The hulking, aging instrument had been decommissioned and left behind by a previous tenant, too old and banged up to bring with them.

Benenato began experimenting with different chemical changes for Moderna's LNPs, but without a working spectrometer she and her colleagues had to have samples ready by noon each day, so they could be picked up by an outside company that would perform the necessary analysis. After a few weeks, her superiors received an enormous bill for the outsourced work and decided to pay to get the old spectrometer running again.

After months of futility, Benenato became impatient. An overachiever who could be hard on herself, she was eager to impress her new bosses. Benenato felt pressure outside the office, as well. She was married with a preschool-age daughter and an eighteen-month-old son. In her last job, Benenato's commute had been a twenty-minute trip to Astra-Zeneca's office in Waltham, outside Boston; now she was traveling an hour to Moderna's Cambridge offices. She became anxious—how was she going to devote the long hours she realized were necessary to solve their LNP quandary while providing her children proper care? Joining Moderna was beginning to feel like a possible mistake.

She turned to her husband and father for help. They reminded her of the hard work she had devoted to establishing her career and said it would be a shame if she couldn't take on the new challenge. Benenato's husband said he was happy to stay home with the kids, alleviating some of her concerns.

Back in the office, she got to work. She wanted to make lipids that were easier for the body to chop into smaller pieces, so they could be eliminated by the body's enzymes. Until then, Moderna, like most others, relied on all kinds of complicated chemicals to hold its LNP packaging together. They weren't natural, though, so the body was having a hard time breaking them down, causing the toxicity.

Benenato began experimenting with simpler chemicals. She inserted "ester bonds"—compounds referred to in chemical circles as "handles" because the body easily grabs them and breaks them apart. Ester bonds had two things going for them: They were strong enough to help ensure the LNP remained stable, acting much like a drop of oil in water, but they also gave the body's enzymes something to target and break down as soon as the LNP entered the cell, a way to quickly rid the body of the potentially toxic LNP components. Benenato thought the inclusion of these chemicals might speed the elimination of the LNP delivery material.

This idea, Benenato realized, was nothing more than traditional, medicinal chemistry. Most people didn't use ester bonds because they were pretty unsophisticated. But, hey, the tricky stuff wasn't working, so Benenato thought she'd see if the simple stuff worked.

Benenato also wanted to try to replace a group of unnatural chemicals in the LNP that was contributing to the spirited and unwelcome response from the immune system. Benenato set out to build a new and improved chemical combination. She began with ethanolamine, a colorless, natural chemical, an obvious start for any chemist hoping to build a more complex chemical combination. No one relied on ethanolamine on its own.

Benenato was curious, though. What would happen if she used just these two simple modifications to the LNP: ethanolamine with the ester bonds? Right away, Benenato noticed her new, super-simple compound helped mRNA create some protein in animals. It wasn't much, but it was a surprising and positive sign. Benenato spent over a year refining her solution, testing more than one hundred variations, all using ethanolamine and ester bonds, showing improvements with each new version of LNP. After finishing her 102nd version of the lipid molecule, which she named SM102, Benenato was confident enough in her work to show it to Hoge and others.

They immediately got excited. The team kept tweaking the composition of the lipid encasement. In 2017, they wrapped it around mRNA molecules and injected the new combination in mice and then monkeys. They saw plentiful, potent proteins were being produced and the lipids were quickly being eliminated, just as Benenato and her colleagues had hoped. Moderna had its special sauce.

That year, Benenato was asked to deliver a presentation to Stephane Bancel, Moderna's chief executive, Afeyan, and Moderna's executive committee to explain why it made sense to use the new, simpler LNP formulation for all its mRNA vaccines. She still needed approval from the executives to make the change. Ahead of the meeting, she was apprehensive, as some of her earlier anxieties returned. But an unusual calm came over her as she began speaking to the group. Benenato explained how experimenting with basic, overlooked chemicals had led to her discovery.

She said she had merely stumbled onto the company's solution, though her bosses understood the efforts that had been necessary for the breakthrough. The board complimented her work and agreed with the idea of switching to the new LNP. Benenato beamed with pride.

"As a scientist, serendipity has been my best friend," she told the executives.

Over the next few years, Benenato and her colleagues would improve on their methods and develop even more tolerable and potent LNP encasement for mRNA molecules. Their work enabled Moderna to include higher doses of vaccine in its shots. In early 2020, Moderna developed Covid-19 shots that included 100 micrograms of vaccine, compared with 30 micrograms in the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. That difference appears to help the Moderna vaccine generate higher titers and provide more protection.

"You set out in a career in drug discovery to want to make a difference," Benenato says. "Seeing it come to reality has been surreal and emotional."

Editor's Note: This essay is excerpted from A SHOT TO SAVE THE WORLD: The Inside Story of the Life-or-Death Race for a COVID-19 Vaccine by Gregory Zuckerman, now on sale from Portfolio/Penguin.

*Jason Schrum's arthritis is now in complete remission, thanks to Humira (adalimumab), a TNF-alpha blocker.

DNA- and RNA-based electronic implants may revolutionize healthcare

The test tubes contain tiny DNA/enzyme-based circuits, which comprise TRUMPET, a new type of electronic device, smaller than a cell.

Implantable electronic devices can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. A pacemaker can encourage the heart to beat more regularly. A neural implant, usually placed at the back of the skull, can help brain function and encourage higher neural activity. Current research on neural implants finds them helpful to patients with Parkinson’s disease, vision loss, hearing loss, and other nerve damage problems. Several of these implants, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink, have already been approved by the FDA for human use.

Yet, pacemakers, neural implants, and other such electronic devices are not without problems. They require constant electricity, limited through batteries that need replacements. They also cause scarring. “The problem with doing this with electronics is that scar tissue forms,” explains Kate Adamala, an assistant professor of cell biology at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. “Anytime you have something hard interacting with something soft [like muscle, skin, or tissue], the soft thing will scar. That's why there are no long-term neural implants right now.” To overcome these challenges, scientists are turning to biocomputing processes that use organic materials like DNA and RNA. Other promised benefits include “diagnostics and possibly therapeutic action, operating as nanorobots in living organisms,” writes Evgeny Katz, a professor of bioelectronics at Clarkson University, in his book DNA- And RNA-Based Computing Systems.

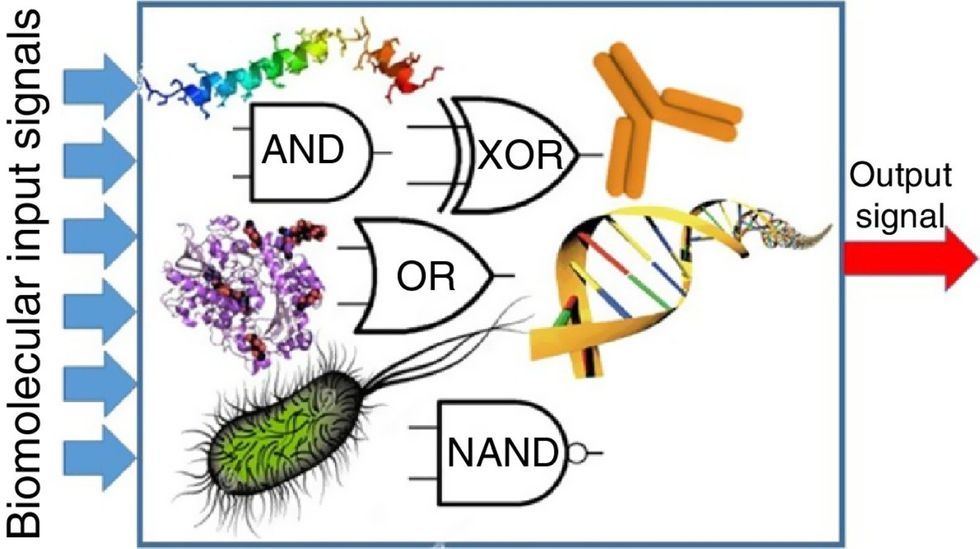

While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output.

Adamala’s research focuses on developing such biocomputing systems using DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Using these molecules in the biocomputing systems allows the latter to be biocompatible with the human body, resulting in a natural healing process. In a recent Nature Communications study, Adamala and her team created a new biocomputing platform called TRUMPET (Transcriptional RNA Universal Multi-Purpose GatE PlaTform) which acts like a DNA-powered computer chip. “These biological systems can heal if you design them correctly,” adds Adamala. “So you can imagine a computer that will eventually heal itself.”

The basics of biocomputing

Biocomputing and regular computing have many similarities. Like regular computing, biocomputing works by running information through a series of gates, usually logic gates. A logic gate works as a fork in the road for an electronic circuit. The input will travel one way or another, giving two different outputs. An example logic gate is the AND gate, which has two inputs (A and B) and two different results. If both A and B are 1, the AND gate output will be 1. If only A is 1 and B is 0, the output will be 0 and vice versa. If both A and B are 0, the result will be 0. While a computer gives these inputs in binary code or "bits," such as a 0 or 1, biocomputing uses DNA strands as inputs, whether double or single-stranded, and often uses fluorescent RNA as an output. In this case, the DNA enters the logic gate as a single or double strand.

If the DNA is double-stranded, the system “digests” the DNA or destroys it, which results in non-fluorescence or “0” output. Conversely, if the DNA is single-stranded, it won’t be digested and instead will be copied by several enzymes in the biocomputing system, resulting in fluorescent RNA or a “1” output. And the output for this type of binary system can be expanded beyond fluorescence or not. For example, a “1” output might be the production of the enzyme insulin, while a “0” may be that no insulin is produced. “This kind of synergy between biology and computation is the essence of biocomputing,” says Stephanie Forrest, a professor and the director of the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society at Arizona State University.

Biocomputing circles are made of DNA, RNA, proteins and even bacteria.

Evgeny Katz

The TRUMPET’s promise

Depending on whether the biocomputing system is placed directly inside a cell within the human body, or run in a test-tube, different environmental factors play a role. When an output is produced inside a cell, the cell's natural processes can amplify this output (for example, a specific protein or DNA strand), creating a solid signal. However, these cells can also be very leaky. “You want the cells to do the thing you ask them to do before they finish whatever their businesses, which is to grow, replicate, metabolize,” Adamala explains. “However, often the gate may be triggered without the right inputs, creating a false positive signal. So that's why natural logic gates are often leaky." While biocomputing outside a cell in a test tube can allow for tighter control over the logic gates, the outputs or signals cannot be amplified by a cell and are less potent.

TRUMPET, which is smaller than a cell, taps into both cellular and non-cellular biocomputing benefits. “At its core, it is a nonliving logic gate system,” Adamala states, “It's a DNA-based logic gate system. But because we use enzymes, and the readout is enzymatic [where an enzyme replicates the fluorescent RNA], we end up with signal amplification." This readout means that the output from the TRUMPET system, a fluorescent RNA strand, can be replicated by nearby enzymes in the platform, making the light signal stronger. "So it combines the best of both worlds,” Adamala adds.

These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body.

The TRUMPET biocomputing process is relatively straightforward. “If the DNA [input] shows up as single-stranded, it will not be digested [by the logic gate], and you get this nice fluorescent output as the RNA is made from the single-stranded DNA, and that's a 1,” Adamala explains. "And if the DNA input is double-stranded, it gets digested by the enzymes in the logic gate, and there is no RNA created from the DNA, so there is no fluorescence, and the output is 0." On the story's leading image above, if the tube is "lit" with a purple color, that is a binary 1 signal for computing. If it's "off" it is a 0.

While still in research, TRUMPET and other biocomputing systems promise significant benefits to personalized healthcare and medicine. These organic-based systems could detect cancer cells or low insulin levels inside a patient’s body. The study’s lead author and graduate student Judee Sharon is already beginning to research TRUMPET's ability for earlier cancer diagnoses. Because the inputs for TRUMPET are single or double-stranded DNA, any mutated or cancerous DNA could theoretically be detected from the platform through the biocomputing process. Theoretically, devices like TRUMPET could be used to detect cancer and other diseases earlier.

Adamala sees TRUMPET not only as a detection system but also as a potential cancer drug delivery system. “Ideally, you would like the drug only to turn on when it senses the presence of a cancer cell. And that's how we use the logic gates, which work in response to inputs like cancerous DNA. Then the output can be the production of a small molecule or the release of a small molecule that can then go and kill what needs killing, in this case, a cancer cell. So we would like to develop applications that use this technology to control the logic gate response of a drug’s delivery to a cell.”

Although platforms like TRUMPET are making progress, a lot more work must be done before they can be used commercially. “The process of translating mechanisms and architecture from biology to computing and vice versa is still an art rather than a science,” says Forrest. “It requires deep computer science and biology knowledge,” she adds. “Some people have compared interdisciplinary science to fusion restaurants—not all combinations are successful, but when they are, the results are remarkable.”

Crickets are low on fat, high on protein, and can be farmed sustainably. They are also crunchy.

In today’s podcast episode, Leaps.org Deputy Editor Lina Zeldovich speaks about the health and ecological benefits of farming crickets for human consumption with Bicky Nguyen, who joins Lina from Vietnam. Bicky and her business partner Nam Dang operate an insect farm named CricketOne. Motivated by the idea of sustainable and healthy protein production, they started their unconventional endeavor a few years ago, despite numerous naysayers who didn’t believe that humans would ever consider munching on bugs.

Yet, making creepy crawlers part of our diet offers many health and planetary advantages. Food production needs to match the rise in global population, estimated to reach 10 billion by 2050. One challenge is that some of our current practices are inefficient, polluting and wasteful. According to nonprofit EarthSave.org, it takes 2,500 gallons of water, 12 pounds of grain, 35 pounds of topsoil and the energy equivalent of one gallon of gasoline to produce one pound of feedlot beef, although exact statistics vary between sources.

Meanwhile, insects are easy to grow, high on protein and low on fat. When roasted with salt, they make crunchy snacks. When chopped up, they transform into delicious pâtes, says Bicky, who invents her own cricket recipes and serves them at industry and public events. Maybe that’s why some research predicts that edible insects market may grow to almost $10 billion by 2030. Tune in for a delectable chat on this alternative and sustainable protein.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Further reading:

More info on Bicky Nguyen

https://yseali.fulbright.edu.vn/en/faculty/bicky-n...

The environmental footprint of beef production

https://www.earthsave.org/environment.htm

https://www.watercalculator.org/news/articles/beef-king-big-water-footprints/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005/full

https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

Insect farming as a source of sustainable protein

https://www.insectgourmet.com/insect-farming-growing-bugs-for-protein/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/insect-farming

Cricket flour is taking the world by storm

https://www.cricketflours.com/

https://talk-commerce.com/blog/what-brands-use-cricket-flour-and-why/

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.