CRISPR base editing gives measure of hope to people with muscular dystrophy

Next year, a neurologist will test CRISPR base editing in a trial of five people with muscular dystrophy to see if their muscles accept corrected cells and whether they multiply and take over the function of damaged cells.

When Martin Weber climbs the steps to his apartment on the fifth floor in Munich, an attentive observer might notice that he walks a little unevenly. “That’s because my calf muscles were the first to lose strength,” Weber explains.

About three years ago, the now 19-year-old university student realized that he suddenly had trouble keeping up with his track team at school. At tennis tournaments, he seemed to lose stamina after the first hour. “But it was still within the norm,” he says. “So it took a while before I noticed something was seriously wrong.” A blood test showed highly elevated liver markers. His parents feared he had liver cancer until a week-long hospital visit and scores of tests led to a diagnosis: hereditary limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, an incurable genetic illness that causes muscles to deteriorate.

As you read this text, you will surely use several muscles without being aware of them: Your heart muscle pumps blood through your arteries, your eye muscles let you follow the words in this sentence, and your hand muscles hold the tablet or cell phone. Muscles make up 40 percent of your body weight; we usually have 656 of them. Now imagine they are slowly losing their strength. No training, no protein shake can rebuild their function.

This is the reality for most people in Simone Spuler’s outpatient clinic at the Charité Hospital in Berlin, Germany: Almost all of her 2,500 patients have muscular dystrophy, a progressive illness striking mostly young people. Muscle decline leads to a wheelchair and, eventually, an early death due to a heart attack or the inability to breathe. In Germany alone, 300,000 people live with this illness, the youngest barely a year old. The CDC estimates that its most common form, Duchenne, affects 1 in every 3,500 to 6,000 male births each year in the United States.

The devastating progression of the disease is what motivates Spuler and her team of 25 scientists to find a cure. In 2019, they made a spectacular breakthrough: For the first time, they successfully used mRNA to introduce the CRISPR-Cas9 tool into human muscle stem cells to repair the dystrophy. “It’s really just one tiny molecule that doesn’t work properly,” Spuler explains.

CRISPR-Cas9 is a technology that lets scientists select and alter parts of the genome. It’s still comparatively new but has advanced quickly since its discovery in the early 2010s. “We now have the possibility to repair certain mutations with genetic editing,” Spuler says. “It’s pure magic.”

She projects a warm, motherly air and a professional calm that inspires trust from her patients. She needs these qualities because the 60-year-old neurologist has one of the toughest jobs in the world: All day long, patients with the incurable diagnosis of muscular dystrophy come to her clinic, and she watches them decline over the years. “Apart from physiotherapy, there is nothing we can recommend right now,” she says. That motivated her early in her career, when she met her first patients at the Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology near Munich in the 1990s. “I knew I had 30, 40 years to find something.”

She learned from the luminaries of her profession with postdocs at the University of California San Diego, Harvard and Johns Hopkins, before serving as a clinical fellow at the Mayo Clinic. In 2005, the Charité offered her the opportunity to establish a specialized clinic for myasthenia, or muscular weakness. An important influence on Spuler, she says, has been the French microbiologist Emmanuelle Charpentier, who received the Nobel Prize in 2020 along with Jennifer Doudna for their CRISPR research, and has worked in Berlin since 2015.

When CRISPR was first introduced, it was mainly used to cut through DNA. However, the cut can lead to undesired side effects. For the muscle stem cells, Spuler now uses a base editor to repair the damaged molecule with super fine scissors or tweezers.

“Apart from physiotherapy, there is nothing we can recommend right now,” Spuler says about her patients with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy.

Pablo Castagnola

Last year, she proved that the method works in mice. Injecting repaired cells into the rodents led to new muscle fibers and, in 2021 and 2022, she passed the first safety meetings with the Paul-Ehrlich Institute, which is responsible for approving human gene editing trials in Germany. She raised the nearly four million Euros needed to test the new method in the first clinical trial in humans with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, beginning with one muscle that can easily be measured, such as the biceps.

This spring, Weber and his parents drove the 400 miles from Munich to Berlin. At Spuler’s lab, her team took a biopsy from muscles in his left arm. The first two steps – extraction and repair in a culture dish – went according to plan; Spuler was able to repair the mutation in Weber’s cells outside his body.

Next year, Weber will be the youngest participant when Spuler starts to test the method in a trial of five people “in vivo,” inside their bodies. This will be the real moment of truth: Will the participants’ muscles accept the corrected cells? Will the cells multiply and take over the function of damaged cells, just like Spuler was able to do in her lab with the rodents?

The effort is costly and complex. “The biggest challenge is to make absolutely sure that we don’t harm the patient,” Spuler says. This means scanning their entire genomes, “so we don’t accidentally damage or knock out an important gene.”

Weber, who asked not to be identified by his real name, is looking forward to the trial and he feels confident that “the risks are comparatively small because the method will only be applied to one muscle. The worst that can happen is that it doesn’t work. But in the best case, the muscle function will improve.”

He was so impressed with the Charité scientists that he decided to study biology at his university. He’s read extensively about CRISPR, so he understands why he has three healthy siblings. “That’s the statistics,” the biologist in training explains. “You get two sets of genes from each parent, and you have to get two faulty mutations to have muscular dystrophy. So we fit the statistics exactly: One of us four kids inherited the mutation.”

It was his mother, a college teacher, and father, a physicist by training, who heard about Spuler’s research. Even though Weber does not live at home anymore, having a chronically ill son is nearly a full-time job for his mother, Annette. The Berlin visit and the trial are financed separately through private sponsors, but the fights with Weber’s health insurance are frustrating and time-consuming. “Physiotherapy is the only thing that helps a bit,” Weber says, “and yet, they fought us on approving it every step of the way.”

Spuler does not want to evoke unrealistic expectations. “Patients who are wheelchair-bound won’t suddenly get up and walk."

Her son continues to exercise as much as possible. Riding his bicycle to the university has become too difficult, so he got an e-scooter. He had to give up competitive tennis because he does not have the stamina for a two-hour match, but he can still play with his dad or his buddies for an hour. His closest friends know about the diagnosis. “They help me, for instance, to lift something heavy because I can’t do that anymore,” Weber says.

The family was elated to find medical support at the Munich Muscle Center by the German Alliance for Muscular Patients and then at Spuler’s clinic in Berlin. “When you hear that this is a progressive illness with no chance of improvement, your world collapses as a parent,” Annette Weber says. “And then all of a sudden, there is this woman who sees scientific progress as an opportunity. Even just to be able to participate in the study is fantastic.”

Spuler does not want to evoke unrealistic expectations. “Patients who are wheelchair-bound won’t suddenly get up and walk,” she says. After all, she will start by applying the gene editor to only one muscle, “but it would be a big step if even a small muscle that is essential to grip something, or to swallow, regains function.”

Weber agrees. “I understand that I won’t regain 100 percent of my muscle function but even a small improvement or at least halting the deterioration is the goal.”

And yet, Spuler and others are ultimately searching for a true solution. In a separate effort, Massachusetts-based biotech company Sarepta announced this month it will seek expedited regulators’ approval to treat Duchenne patients with its investigational gene therapy. Unlike Spuler’s methods, Sarepta focuses specifically on the Duchenne form of muscular dystrophy, and it uses an adeno-assisted virus to deliver the therapy.

Spuler’s vision is to eventually apply gene editing to the entire body of her patients. To speed up the research, she and a colleague founded a private research company, Myopax. If she is able to prove that the body accepts the edited cells, the technique could be used for other monogenetic illnesses as well. “When we speak of genetic editing, many are scared and say, oh no, this is God’s work,” says Spuler. But she sees herself as a mechanic, not a divine being. “We really just exchange a molecule, that’s it.”

If everything goes well, Weber hopes that ten years from now, he will be the one taking biopsies from the next generation of patients and repairing their genes.

Scientists Are Working to Decipher the Puzzle of ‘Broken Heart Syndrome’

Elaine Kamil had just returned home after a few days of business meetings in 2013 when she started having chest pains. At first Kamil, then 66, wasn't worried—she had had some chest pain before and recently went to a cardiologist to do a stress test, which was normal.

"I can't be having a heart attack because I just got checked," she thought, attributing the discomfort to stress and high demands of her job. A pediatric nephrologist at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, she takes care of critically ill children who are on dialysis or are kidney transplant patients. Supporting families through difficult times and answering calls at odd hours is part of her daily routine, and often leaves her exhausted.

She figured the pain would go away. But instead, it intensified that night. Kamil's husband drove her to the Cedars-Sinai hospital, where she was admitted to the coronary care unit. It turned out she wasn't having a heart attack after all. Instead, she was diagnosed with a much less common but nonetheless dangerous heart condition called takotsubo syndrome, or broken heart syndrome.

A heart attack happens when blood flow to the heart is obstructed—such as when an artery is blocked—causing heart muscle tissue to die. In takotsubo syndrome, the blood flow isn't blocked, but the heart doesn't pump it properly. The heart changes its shape and starts to resemble a Japanese fishing device called tako-tsubo, a clay pot with a wider body and narrower mouth, used to catch octopus.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks," explains Noel Bairey Merz, the cardiologist at Cedar Sinai who Kamil went to see after she was discharged.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks."

But even though the heart isn't permanently damaged, mortality rates due to takotsubo syndrome are comparable to those of a heart attack, Merz notes—about 4-5 percent of patients die from the attack, and 20 percent within the next five years. "It's as bad as a heart attack," Merz says—only it's much less known, even to doctors. The condition affects only about 1 percent of people, and there are around 15,000 new cases annually. It's diagnosed using a cardiac ventriculogram, an imaging test that allows doctors to see how the heart pumps blood.

Scientists don't fully understand what causes Takotsubo syndrome, but it usually occurs after extreme emotional or physical stress. Doctors think it's triggered by a so-called catecholamine storm, a phenomenon in which the body releases too much catecholamines—hormones involved in the fight-or-flight response. Evolutionarily, when early humans lived in savannas or forests and had to either fight off predators or flee from them, these hormones gave our ancestors the needed strength and stamina to take either action. Released by nerve endings and by the adrenal glands that sit on top of the kidneys, these hormones still flood our bodies in moments of stress, but an overabundance of them could sometimes be damaging.

Elaine Kamil

A study by scientists at Harvard Medical School linked increased risk of takotsubo to higher activity in the amygdala, a brain region responsible for emotions that's involved in responses to stress. The scientists believe that chronic stress makes people more susceptible to the syndrome. Notably, one small study suggested that the number of Takotsubo cases increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are no specific drugs to treat takotsubo, so doctors rely on supportive therapies, which include medications typically used for high blood pressure and heart failure. In most cases, the heart returns to its normal shape within a few weeks. "It's a spontaneous recovery—the catecholamine storm is resolved, the injury trigger is removed and the heart heals itself because our bodies have an amazing healing capacity," Merz says. It also helps that tissues remain intact. 'The heart cells don't die, they just aren't functioning properly for some time."

That's the good news. The bad news is that takotsubo is likely to strike again—in 5-20 percent of patients the condition comes back, sometimes more severe than before.

That's exactly what happened to Kamil. After getting her diagnosis in 2013, she realized that she actually had a previous takotsubo episode. In 2010, she experienced similar symptoms after her son died. "The night after he died, I was having severe chest pain at night, but I was too overwhelmed with grief to do anything about it," she recalls. After a while, the pain subsided and didn't return until three years later.

For weeks after her second attack, she felt exhausted, listless and anxious. "You lose confidence in your body," she says. "You have these little twinges on your chest, or if you start having arrhythmia, and you wonder if this is another episode coming up. It's really unnerving because you don't know how to read these cues." And that's very typical, Merz says. Even when the heart muscle appears to recover, patients don't return to normal right away. They have shortens of breath, they can't exercise, and they stay anxious and worried for a while.

Women over the age of 50 are diagnosed with takotsubo more often than other demographics. However, it happens in men too, although it typically strikes after physical stress, such as a triathlon or an exhausting day of cycling. Young people can also get takotsubo. Older patients are hospitalized more often, but younger people tend to have more severe complications. It could be because an older person may go for a jog while younger one may run a marathon, which would take a stronger toll on the body of a person who's predisposed to the condition.

Notably, the emotional stressors don't always have to be negative—the heart muscle can get out of shape from good emotions, too. "There have been case reports of takotsubo at weddings," Merz says. Moreover, one out of three or four takotsubo patients experience no apparent stress, she adds. "So it could be that it's not so much the catecholamine storm itself, but the body's reaction to it—the physiological reaction deeply embedded into out physiology," she explains.

Merz and her team are working to understand what makes people predisposed to takotsubo. They think a person's genetics play a role, but they haven't yet pinpointed genes that seem to be responsible. Genes code for proteins, which affect how the body metabolizes various compounds, which, in turn, affect the body's response to stress. Pinning down the protein involved in takotsubo susceptibility would allow doctors to develop screening tests and identify those prone to severe repeating attacks. It will also help develop medications that can either prevent it or treat it better than just waiting for the body to heal itself.

Researchers at the Imperial College London found that elevated levels of certain types of microRNAs—molecules involved in protein production—increase the chances of developing takotsubo.

In one study, researchers tried treating takotsubo in mice with a drug called suberanilohydroxamic acid, or SAHA, typically used for cancer treatment. The drug improved cardiac health and reversed the broken heart in rodents. It remains to be seen if the drug would have a similar effect on humans. But identifying a drug that shows promise is progress, Merz says. "I'm glad that there's research in this area."

This article was originally published by Leaps.org on July 28, 2021.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

Did Anton the AI find a new treatment for a deadly cancer?

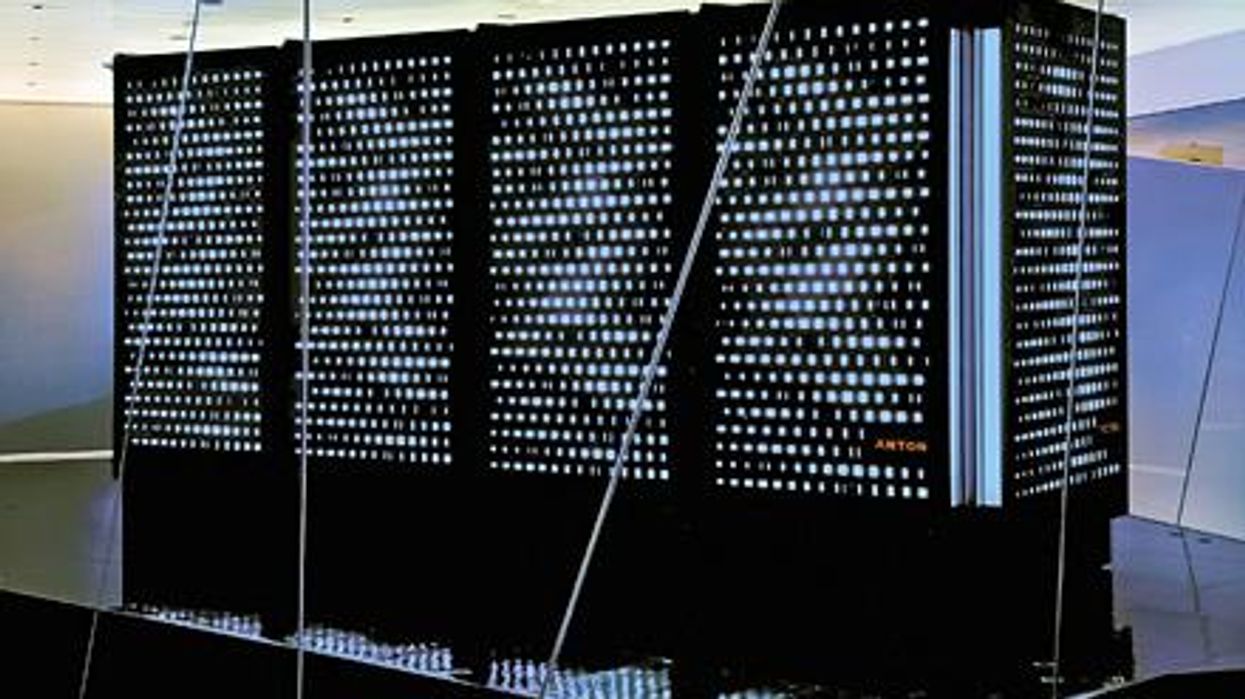

Researchers used a supercomputer to learn about the subtle movement of a cancer-causing molecule, and then they found the precise drug that can recognize that motion.

Bile duct cancer is a rare and aggressive form of cancer that is often difficult to diagnose. Patients with advanced forms of the disease have an average life expectancy of less than two years.

Many patients who get cancer in their bile ducts – the tubes that carry digestive fluid from the liver to the small intestine – have mutations in the protein FGFR2, which leads cells to grow uncontrollably. One treatment option is chemotherapy, but it’s toxic to both cancer cells and healthy cells, failing to distinguish between the two. Increasingly, cancer researchers are focusing on biomarker directed therapy, or making drugs that target a particular molecule that causes the disease – FGFR2, in the case of bile duct cancer.

A problem is that in targeting FGFR2, these drugs inadvertently inhibit the FGFR1 protein, which looks almost identical. This causes elevated phosphate levels, which is a sign of kidney damage, so doses are often limited to prevent complications.

In recent years, though, a company called Relay has taken a unique approach to picking out FGFR2, using a powerful supercomputer to simulate how proteins move and change shape. The team, leveraging this AI capability, discovered that FGFR2 and FGFR1 move differently, which enabled them to create a more precise drug.

Preliminary studies have shown robust activity of this drug, called RLY-4008, in FGFR2 altered tumors, especially in bile duct cancer. The drug did not inhibit FGFR1 or cause significant side effects. “RLY-4008 is a prime example of a precision oncology therapeutic with its highly selective and potent targeting of FGFR2 genetic alterations and resistance mutations,” says Lipika Goyal, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. She is a principal investigator of Relay’s phase 1-2 clinical trial.

Boosts from AI and a billionaire

Traditional drug design has been very much a case of trial and error, as scientists investigate many molecules to see which ones bind to the intended target and bind less to other targets.

“It’s being done almost blindly, without really being guided by structure, so it fails very often,” says Olivier Elemento, associate director of the Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Cornell. “The issue is that they are not sampling enough molecules to cover some of the chemical space that would be specific to the target of interest and not specific to others.”

Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

Some scientists have tried to use X-rays of crystallized proteins to look at the structure of proteins and design better drugs. But they have failed to account for an important factor: proteins are moving and constantly folding into different shapes.

David Shaw, a hedge fund billionaire, wanted to help improve drug discovery and understood that a key obstacle was that computer models of molecular dynamics were limited; they simulated motion for less than 10 millionths of a second.

In 2001, Shaw set up his own research facility, D.E. Shaw Research, to create a supercomputer that would be specifically designed to simulate protein motion. Seven years later, he succeeded in firing up a supercomputer that can now conduct high speed simulations roughly 100 times faster than others. Called Anton, it has special computer chips to enable this speed, and its software is powered by AI to conduct many simulations.

After creating the supercomputer, Shaw teamed up with leading scientists who were interested in molecular motion, and they founded Relay Therapeutics.

Elemento believes that Relay’s approach is highly beneficial in designing a better drug for bile duct cancer. “Relay Therapeutics has a cutting-edge approach for molecular dynamics that I don’t believe any other companies have, at least not as advanced.” Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

How it works

Relay used both experimental and computational approaches to design RLY-4008. The team started out by taking X-rays of crystallized versions of both their intended target, FGFR2, and the almost identical FGFR1. This enabled them to get a 3D snapshot of each of their structures. They then fed the X-rays into the Anton supercomputer to simulate how the proteins were likely to move.

Anton’s simulations showed that the FGFR1 protein had a flap that moved more frequently than FGFR2. Based on this distinct motion, the team tried to design a compound that would recognize this flap shifting around and bind to FGFR2 while steering away from its more active lookalike.

For that, they went back Anton, using the supercomputer to simulate the behavior of thousands of potential molecules for over a year, looking at what made a particular molecule selective to the target versus another molecule that wasn’t. These insights led them to determine the best compounds to make and test in the lab and, ultimately, they found that RLY-4008 was the most effective.

Promising results so far

Relay began phase 1-2 trials in 2020 and will continue until 2024. Preliminary results showed that, in the 17 patients taking a 70 mg dose of RLY-4008, the drug worked to shrink tumors in 88 percent of patients. This was a significant increase compared to other FGFR inhibitors. For instance, Futibatinib, which recently got FDA approval, had a response rate of only 42 percent.

Across all dose levels, RLY-4008 shrank tumors by 63 percent in 38 patients. In more good news, the drug didn’t elevate their phosphate levels, which suggests that it could be taken without increasing patients’ risk for kidney disease.

“Objectively, this is pretty remarkable,” says Elemento. “In a small patient study, you have a molecule that is able to shrink tumors in such a high fraction of patients. It is unusual to see such good results in a phase 1-2 trial.”

A simulated future

The research team is continuing to use molecular dynamic simulations to develop other new drug, such as one that is being studied in patients with solid tumors and breast cancer.

As for their bile duct cancer drug, RLY-4008, Relay plans by 2024 to have tested it in around 440 patients. “The mature results of the phase 1-2 trial are highly anticipated,” says Goyal, the principal investigator of the trial.

Sameek Roychowdhury, an oncologist and associate professor of internal medicine at Ohio State University, highlights the need for caution. “This has early signs of benefit, but we will look forward to seeing longer term results for benefit and side effect profiles. We need to think a few more steps ahead - these treatments are like the ’Whack-a-Mole game’ where cancer finds a way to become resistant to each subsequent drug.”

“I think the issue is going to be how durable are the responses to the drug and what are the mechanisms of resistance,” says Raymond Wadlow, an oncologist at the Inova Medical Group who specializes in gastrointestinal and haematological cancer. “But the results look promising. It is a much more selective inhibitor of the FGFR protein and less toxic. It’s been an exciting development.”