New Hope for Organ Transplantation: Life Without Anti-Rejection Drugs

Kidney transplant patient Robert Waddell, center, with his wife and children after being off immunosuppresants; photo aken last summer in Perdido Key, FL. Left to right: Christian, Bailey, Rob, Karen (wife), Robby and Casey.

Rob Waddell dreaded getting a kidney transplant. He suffers from a genetic condition called polycystic kidney disease that causes the uncontrolled growth of cysts that gradually choke off kidney function. The inherited defect has haunted his family for generations, killing his great grandmother, grandmother, and numerous cousins, aunts and uncles.

But he saw how difficult it was for his mother and sister, who also suffer from this condition, to live with the side effects of the drugs they needed to take to prevent organ rejection, which can cause diabetes, high blood pressure and cancer, and even kidney failure because of their toxicity. Many of his relatives followed the same course, says Waddell: "They were all on dialysis, then a transplant and ended up usually dying from cancers caused by the medications."

When the Louisville native and father of four hit 40, his kidneys barely functioned and the only alternative was either a transplant or the slow death of dialysis. But in 2009, when Waddell heard about an experimental procedure that could eliminate the need for taking antirejection drugs, he jumped at the chance to be their first patient. Devised by scientists at the University of Louisville and Northwestern University, the innovative approach entails mixing stem cells from the live kidney donor with that of the recipient to create a hybrid immune system, known as a chimera, that would trick the immune system and prevent it from attacking the implanted kidney.

The procedure itself was done at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, using a live kidney donated by a neighbor of Waddell's, who camped out in Chicago during his recovery. Prior to surgery, Waddell underwent a conditioning treatment that consisted of low dose radiation and chemotherapy to weaken his own immune system and make room for the infusion of stem cells.

"The low intensity chemo and radiation conditioning regimen create just enough space for the donor stem cells to gain a foothold in the bone marrow and the donor's immune system takes over," says Dr. Joseph Levanthal, the transplant surgeon who performed the operation and director of kidney and pancreas transplantation at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. "That way the recipient develops an immune system that doesn't see the donor organ as foreign."

"As a surgeon, I saw what my patients had to go through—taking 25 pills a day, dying at an early age from heart disease, or having a 35% chance of dying every year on dialysis."

A week later, Waddell had the kidney transplant. The following day, he was infused with a complex cellular cocktail that included blood-forming stem cells derived from his donor's bone marrow mixed what are called tolerance inducing facilitator cells (FCs); these cells help the foreign stem cells get established in the recipient's bone marrow.

Over the course of the following year, he was slowly weaned off of antirejection medications—a precaution in case the procedure didn't work—and remarkably, hasn't needed them since. "I felt better than I had in decades because my kidneys [had been] degrading," recalls Waddell, now 54 and a CPA for a global beverage company. And what's even better is that this new approach offers hope for one of his sons who has also inherited the disorder.

Kidney transplants are the most frequent organ transplants in the world and more than 23,000 of these procedures were done in the United States in 2019, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing. Of this, about 7,000 operations are done annually using live organ donors; the remainder use organs from people who are deceased. Right now, this revolutionary new approach—as well as a similar strategy formulated by Stanford University scientists--is in the final phase of clinical trials. Ultimately, this research may pave the way towards realizing the holy grail of organ transplantation: preventing organ rejection by creating a tolerant state in which the recipient's immune system is compatible with the donor, which would eliminate the need for a lifetime of medications.

"As a surgeon, I saw what my patients had to go through—taking 25 pills a day, dying at an early age from heart disease, or having a 35% chance of dying every year on dialysis," says Dr. Suzanne Ildstad, a transplant surgeon and director of the Institute for Cellular Therapeutics at the University of Louisville, whose discovery of facilitator cells were the basis for this therapeutic platform. Ildstad, who has spent more than two decades searching for a better way, says, "This is something I have worked for my entire life."

The Louisville group uses a combination of chemo and radiation to replace the recipient's immune and blood forming cells with that of the donor. In contrast, the Stanford protocol involves harvesting the donor's blood stem cells and T-cells, which are the foot soldiers of the immune system that fight off infections and would normally orchestrate the rejection of the transplanted organ. Their transplant recipients undergo a milder form of "conditioning" that only radiates discrete parts of the body and selectively targets the recipient's T-cells, creating room for both sets of T-cells, a strategy these researchers believe has a better safety profile and less of a chance of rejection.

"We try to achieve immune tolerance by a true chimerism," says Dr. Samuel Strober, a professor of medicine for immunology and rheumatology at Stanford University and a leader of this research team. "The recipients immune system cells are maintained but mixed in the blood with that of the donor."

Studies suggest both approaches work. In a 2018 clinical trial conducted by Talaris Therapeutics, a Louisville-based biotech founded by Ildstad, 26 of 37 (70%) of the live donor kidney transplant recipients no longer need immunosuppressants. Last fall, Talaris began the final phase of clinical tests that will eventually encompass more than 120 such patients.

The Stanford group's cell-based immunotherapy, which is called MDR-101 and is sponsored by the South San Francisco biotech, Medeor Therapeutics, has had similar results in patients who received organs from live donors who were either well matched, such as one from siblings, meaning they were immunologically identical, or partially matched; Talaris uses unrelated donors where there is only a partial match.

In their 2020 clinical trial of 51 patients, 29 were fully matched and 22 were a partial match; 22 of the fully matched recipients didn't need antirejection drugs and ten of the partial matches were able to stop taking some of these medications without rejection. "With our fully matched, roughly 80% have been completely off drugs up to 14 years later," says Strober, "and reducing the number of drugs from three to one [in the partial matches] means you have far fewer side effects. The goal is to get them off of all drugs."

But these protocols are limited to a small number of patients—living donor kidney recipients. As a consequence, both teams are experimenting with ways to broaden their approach so they can use cadaver organs from deceased donors, with human tests planned in the coming year. Here's how that would work: after the other organs are removed from a deceased donor, stem cells are harvested from the donor's vertebrae in the spinal column and then frozen for storage.

"We do the transplant and give the patient a chance to recover and maintain them on drugs," says Ildstad. "Then we do the tolerance conditioning at a later stage."

If this strategy is successful, it would be a genuine game changer, and open the door to using these protocols for transplanting other cadaver organs, including the heart, lungs and liver. While the overall procedure is complex and costly, in the long run it's less expensive than repeated transplant surgeries, the cost of medications and hospitalizations for complications caused by the drugs, or thrice weekly dialysis treatments, says Ildstad.

And she adds, you can't put a price tag on the vast improvement in quality of life.

Podcast: The Friday Five Weekly Roundup in Health Research

In this week's Friday Five, a new face mask can detect Covid and send an alert to your phone. Plus, promising research for a breakthrough drug to treat schizophrenia, an AI tool that can create new proteins, progress on a longevity drug - and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- A new mask can detect Covid and send an alert to your phone

- More promising research for a breakthrough drug to treat schizophrenia

- AI tool can create new proteins

- Connections between an unhealthy gut and breast cancer

- Progress on the longevity drug, rapamycin

And an honorable mention this week: Certain exercises may benefit some types of memory more than others

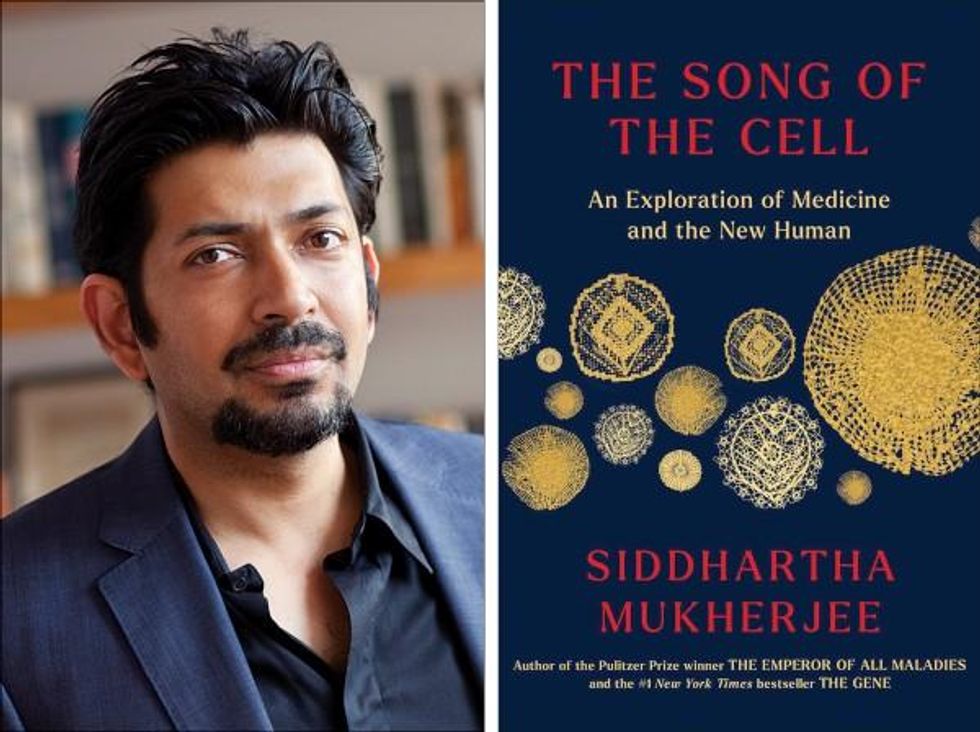

Life is Emerging: Review of Siddhartha Mukherjee’s Song of the Cell

A new book by Pulitzer-winning physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee will be released from Simon & Schuster on October 25, 2022.

The DNA double helix is often the image spiraling at the center of 21st century advances in biomedicine and the growing bioeconomy. And yet, DNA is molecularly inert. DNA, the code for genes, is not alive and is not strictly necessary for life. Ought life be at the center of our communication of living systems? Is not the Cell a superior symbol of life and our manipulation of living systems?

A code for life isn’t a code without the life that instantiates it. A code for life must be translated. The cell is the basic unit of that translation. The cell is the minimal viable package of life as we know it. Therefore, cell biology is at the center of biomedicine’s greatest transformations, suggests Pulitzer-winning physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee in his latest book, The Song of the Cell: The Exploration of Medicine and the New Human.

The Song of the Cell begins with the discovery of cells and of germ theory, featuring characters such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, who brought the cell “into intimate contact with pathology and medicine.” This intercourse would transform biomedicine, leading to the insight that we can treat disease by thinking at the cellular level. The slightest rearrangement of sick cells might be the path toward alleviating suffering for the organism: eroding the cell walls of a bacterium while sparing our human cells; inventing a medium that coaxes sperm and egg to dance into cellular union for in vitro fertilization (IVF); designing molecular missiles that home to the receptors decorating the exterior of cancer cells; teaching adult skin cells to remember their embryonic state for regenerative medicines.

Mukherjee uses the bulk of the book to elucidate key cell types in the human body, along with their “connective relationships” that enable key organs and organ systems to function. This includes the immune system, the heart, the brain, and so on. Mukherjee’s distinctive style features compelling anecdotes and human stories that animate the scientific (and unscientific) processes that have led to our current state of understanding. In his chapter on neurons and the brain, for example, he integrates Santiago Ramon y Cajal’s meticulous black ink sketches of neurons into Mukherjee’s own personal encounter with clinical depression. In one lucid section, he interviews Dr. Helen Mayberg, a pioneering neurologist who takes seriously the descriptive power of her patients’ metaphors, as they suffer from “caves,” “holes,” “voids,” and “force fields” that render their lives gray. Dr. Mayberg aims to stimulate patients’ neuronal cells in a manner that brings back the color.

Beyond exposing the insight and inventiveness that has arisen out of cell-based thinking, it seems that Mukherjee’s bigger project is an epistemological one. The early chapters of The Song of the Cell continually hint at the potential for redefining the basic unit of biology as the cell rather than the gene. The choice to center biomedicine around cells is, above all, a conspicuous choice not to center it around genes (the subject of Mukherjee’s previous book, The Gene), because genes dominate popular science communication.

This choice of cells over genes is most welcome. Cells are alive. Genes are not. Letters—such as the As, Cs, Gs, and Ts that represent the nucleotides of DNA, which make up our genes—must be synthesized into a word or poem or song that offers a glimpse into deeper truths. A key idea embedded in this thinking is that of emergence. Whether in ancient myth or modern art, creation tends to be an emergent process, not a linearly coded script. The cell is our current best guess for the basic unit of life’s emergence, turning a finite set of chemical building blocks—nucleic acids, proteins, sugars, fats—into a replicative, evolving system for fighting stasis and entropy. The cell’s song is one for our times, for it is the song of biology’s emergence out of chemistry and physics, into the “frenetically active process” of homeostasis.

Re-centering our view of biology has practical consequences, too, for how we think about diagnosing and treating disease, and for inventing new medicines. Centering cells presents a challenge: which type of cell to place at the center? Rather than default to the apparent simplicity of DNA as a symbol because it represents the one master code for life, the tension in defining the diversity of cells—a mapping process still far from complete in cutting-edge biology laboratories—can help to create a more thoughtful library of cellular metaphors to shape both the practice and communication of biology.

Further, effective problem solving is often about operating at the right level, or the right scale. The cell feels like appropriate level at which to interrogate many of the diseases that ail us, because the senses that guide our own perceptions of sickness and health—the smoldering pain of inflammation, the tunnel vision of a migraine, the dizziness of a fluttering heart—are emergent.

This, unfortunately, is sort of where Mukherjee leaves the reader, under-exploring the consequences of a biology of emergence. Many practical and profound questions have to do with the ways that each scale of life feeds back on the others. In a tome on Cells and “the future human” I wished that Mukherjee had created more space for seeking the ways that cells will shape and be shaped by the future, of humanity and otherwise.

We are entering a phase of real-world bioengineering that features the modularization of cellular parts within cells, of cells within organs, of organs within bodies, and of bodies within ecosystems. In this reality, we would be unwise to assume that any whole is the mere sum of its parts.

For example, when discussing the regenerative power of pluripotent stem cells, Mukherjee raises the philosophical thought experiment of the Delphic boat, also known as the Ship of Theseus. The boat is made of many pieces of wood, each of which is replaced for repairs over the years, with the boat’s structure unchanged. Eventually none of the boat’s original wood remains: Is it the same boat?

Mukherjee raises the Delphic boat in one paragraph at the end of the chapter on stem cells, as a metaphor related to the possibility of stem cell-enabled regeneration in perpetuity. He does not follow any of the threads of potential answers. Given the current state of cellular engineering, about which Mukherjee is a world expert from his work as a physician-scientist, this book could have used an entire section dedicated to probing this question and, importantly, the ways this thought experiment falls apart.

We are entering a phase of real-world bioengineering that features the modularization of cellular parts within cells, of cells within organs, of organs within bodies, and of bodies within ecosystems. In this reality, we would be unwise to assume that any whole is the mere sum of its parts. Wholeness at any one of these scales of life—organelle, cell, organ, body, ecosystem—is what is at stake if we allow biological reductionism to assume away the relation between those scales.

In other words, Mukherjee succeeds in providing a masterful and compelling narrative of the lives of many of the cells that emerge to enliven us. Like his previous books, it is a worthwhile read for anyone curious about the role of cells in disease and in health. And yet, he fails to offer the broader context of The Song of the Cell.

As leading agronomist and essayist Wes Jackson has written, “The sequence of amino acids that is at home in the human cell, when produced inside the bacterial cell, does not fold quite right. Something about the E. coli internal environment affects the tertiary structure of the protein and makes it inactive. The whole in this case, the E. coli cell, affects the part—the newly made protein. Where is the priority of part now?” [1]

Beyond the ways that different kingdoms of life translate the same genetic code, the practical situation for humanity today relates to the ways that the different disciplines of modern life use values and culture to influence our genes, cells, bodies, and environment. It may be that humans will soon become a bit like the Delphic boat, infused with the buzz of fresh cells to repopulate different niches within our bodies, for healthier, longer lives. But in biology, as in writing, a mixed metaphor can cause something of a cacophony. For we are not boats with parts to be replaced piecemeal. And nor are whales, nor alpine forests, nor topsoil. Life isn’t a sum of parts, and neither is a song that rings true.

[1] Wes Jackson, "Visions and Assumptions," in Nature as Measure (p. 52-53).