The Skinny on Fat and Covid-19

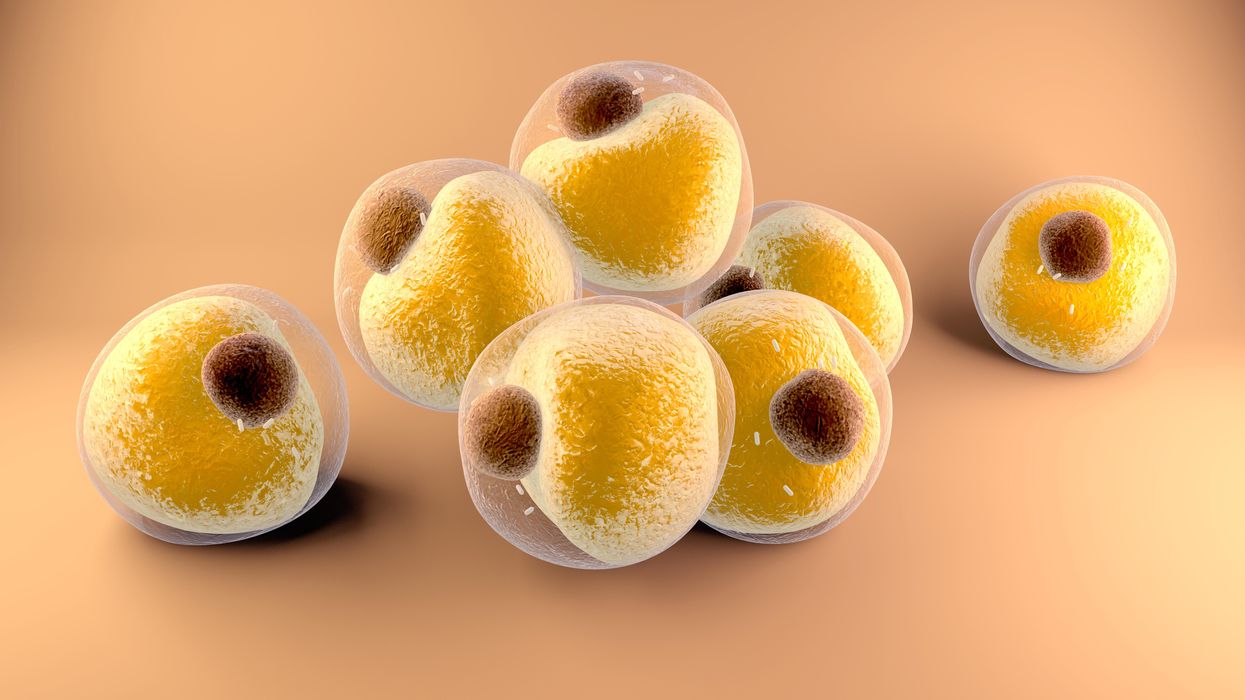

Researchers at Stanford have found that the virus that causes Covid-19 can infect fat cells, which could help explain why obesity is linked to worse outcomes for those who catch Covid-19.

Obesity is a risk factor for worse outcomes for a variety of medical conditions ranging from cancer to Covid-19. Most experts attribute it simply to underlying low-grade inflammation and added weight that make breathing more difficult.

Now researchers have found a more direct reason: SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, can infect adipocytes, more commonly known as fat cells, and macrophages, immune cells that are part of the broader matrix of cells that support fat tissue. Stanford University researchers Catherine Blish and Tracey McLaughlin are senior authors of the study.

Most of us think of fat as the spare tire that can accumulate around the middle as we age, but fat also is present closer to most internal organs. McLaughlin's research has focused on epicardial fat, “which sits right on top of the heart with no physical barrier at all,” she says. So if that fat got infected and inflamed, it might directly affect the heart.” That could help explain cardiovascular problems associated with Covid-19 infections.

Looking at tissue taken from autopsy, there was evidence of SARS-CoV-2 virus inside the fat cells as well as surrounding inflammation. In fat cells and immune cells harvested from health humans, infection in the laboratory drove "an inflammatory response, particularly in the macrophages…They secreted proteins that are typically seen in a cytokine storm” where the immune response runs amok with potential life-threatening consequences. This suggests to McLaughlin “that there could be a regional and even a systemic inflammatory response following infection in fat.”

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

The macrophages studied by McLaughlin and Blish were spewing out inflammatory proteins, While the the virus within them was replicating, the new viral particles were not able to replicate within those cells. It was a different story in the fat cells. “When [the virus] gets into the fat cells, it not only replicates, it's a productive infection, which means the resulting viral particles can infect another cell,” including microphages, McLaughlin explains. It seems to be a symbiotic tango of the virus between the two cell types that keeps the cycle going.

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

Macrophages are mobile; they engulf and carry invading pathogens to lymphoid tissue in the lymph nodes, tonsils and elsewhere in the body to alert T cells of the immune system to the pathogen. Perhaps some of them also carry the virus through the bloodstream to more distant tissue.

ACE2 receptors are the means by which SARS-CoV-2 latches on to and enters most cells. They are not thought to be common on fat cells, so initially most researchers thought it unlikely they would become infected.

However, while some cell receptors always sit on the surface of the cell, other receptors are expressed on the surface only under certain conditions. Philipp Scherer, a professor of internal medicine and director of the Touchstone Diabetes Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, suggests that, in people who have obesity, “There might be higher levels of dysfunctional [fat cells] that facilitate entry of the virus,” either through transiently expressed ACE2 or other receptors. Inflammatory proteins generated by macrophages might contribute to this process.

Another hypothesis is that viral RNA might be smuggled into fat cells as cargo in small bits of material called extracellular vesicles, or EVs, that can travel between cells. Other researchers have shown that when EVs express ACE2 receptors, they can act as decoys for SARS-CoV-2, where the virus binds to them rather than a cell. These scientists are working to create drugs that mimic this decoy effect as an approach to therapy.

Do fat cells play a role in Long Covid? “Fat cells are a great place to hide. You have all the energy you need and fat cells turn over very slowly; they have a half-life of ten years,” says Scherer. Observational studies suggest that acute Covid-19 can trigger the onset of diabetes especially in people who are overweight, and that patients taking medicines to regulate their diabetes “were actually quite protective” against acute Covid-19. Scherer has funding to study the risks and benefits of those drugs in animal models of Long Covid.

McLaughlin says there are two areas of potential concern with fat tissue and Long Covid. One is that this tissue might serve as a “big reservoir where the virus continues to replicate and is sent out” to other parts of the body. The second is that inflammation due to infected fat cells and macrophages can result in fibrosis or scar tissue forming around organs, inhibiting their function. Once scar tissue forms, the tissue damage becomes more difficult to repair.

Current Covid-19 treatments work by stopping the virus from entering cells through the ACE2 receptor, so they likely would have no effect on virus that uses a different mechanism. That means another approach will have to be developed to complement the treatments we already have. So the best advice McLaughlin can offer today is to keep current on vaccinations and boosters and lose weight to reduce the risk associated with obesity.

Are Brain Implants the Future of Treatment for Depression and Anxiety?

Sarah, clinical trial participant, at an appointment with Katherine Scangos, MD, PhD, at UCSF’s Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute.

When she woke up after a procedure involving drilling small holes in her skull, a woman suffering from chronic depression reported feeling “euphoric”. The holes were made to fit the wires that connected her brain with a matchbox-sized electrical implant; this would deliver up to 300 short-lived electricity bursts per day to specific parts of her brain.

Over a year later, Sarah, 36, says the brain implant has turned her life around. A sense of alertness and energy have replaced suicidal thoughts and feelings of despair, which had persisted despite antidepressants and electroconvulsive therapy. Sarah is the first person to have received a brain implant to treat depression, a breakthrough that happened during an experimental study published recently in Nature Medicine.

“What we did was use deep-brain stimulation (DBS), a technique used in the treatment of epilepsy,” says Andrew Krystal, professor of psychiatry at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and one of the study’s researchers. DBS typically involves implanting electrodes into specific areas of the brain to reduce seizures not controlled with medication or to remove the part of the brain that causes the seizures. Instead of choosing and stimulating a single brain site though, the UCSF team took a different approach.

They first used 10 electrodes to map Sarah’s brain activity, a phase that lasted 10 days, during which they developed a neural biomarker, a specific pattern of brain activity that indicated the onset of depression symptoms (in Sarah, this was detected in her amygdala, an almondlike structure located near the base of the brain). But they also saw that delivering a tiny burst of electricity to the patient’s ventral striatum, an area of the brain that sits in the center, above and behind the ears, dramatically improved these symptoms. What they had to do was outfit Sara’s brain with a DBS-device programmed to propagate small waves of electricity to the ventral striatum only when it discerned the pattern.

“We are not trying to take away normal responses to the world. We are just trying to eliminate this one thing, which is depression, which impedes patients’ ability to function and deal with normal stuff.”

“It was a personalized treatment not only in where to stimulate, but when to stimulate,” Krystal says. Sarah’s depression translated to low amounts of energy, loss of pleasure and interest in life, and feelings of sluggishness. Those symptoms went away when scientists stimulated her ventral capsule area. When the same area was manipulated by electricity when Sarah’s symptoms “were not there” though, she was feeling more energetic, but this sudden flush of energy soon gave way to feelings of overstimulation and anxiety. “This is a very tangible illustration of why it's best to simulate only when you need it,” says Krystal.

We have the tendency to lump together depression symptoms, but, in reality, they are quite diverse; some people feel sad and lethargic, others stay up all night; some overeat, others don’t eat at all. “This happens because people have different underlying dysfunctions in different parts of their brain. Our approach is targeting the specific brain circuit that modulates different kinds of symptoms. Simply, where we stimulate depends on the specific set of problems a person has,” Krystal says. Such tailormade brain stimulation for patients with long-term, drug-resistant depression, which would be easy to use at home, could be transformative, the UCSF researcher concludes.

In the U.S., 12.7 percent of the population is on antidepressants. Almost exactly the same percentage of Australians–12.5–take similar drugs every day. With 13 percent of its population being on antidepressants, Iceland is the world’s highest antidepressant consumer. And quite away from Scandinavia, the Southern European country of Portugal is the world’s third strongest market for corresponding medication.

By 2020, nearly 15.5 million people had been consuming antidepressants for a time period exceeding five years. Between 40 and 60 percent of them saw improvements. “For those people, it was absolutely what they needed, whether that was increased serotonin, or increased norepinephrine or increased dopamine, ” says Frank Anderson, a psychiatrist who has been administering antidepressants in his private practice “for a long time”, and author of Transcending Trauma, a book about resolving complex and dissociative trauma.

Yet the UCSF study brings to the mental health field a specificity it has long lacked. “A lot of the traditional medications only really work on six neurotransmitters, when there are over 100 neurotransmitters in the brain,” Anderson says. Drugs are changing the chemistry of a single system in the brain, but brain stimulation is essentially changing the very architecture of the brain, says James Giordano, professor of neurology and biochemistry at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington and a neuroethicist. It is a far more elegant approach to treating brain disorders, with the potential to prove a lifesaver for the 40 to 50 percent of patients who see no benefits at all with antidepressants, Giordano says. It is neurofeedback, on steroids, adds Anderson. But it comes with certain risks.

Even if the device generating the brain stimulation sits outside the skull and could be easily used at home, the whole process still involves neurosurgery. While the sophistication and precision of brain surgeries has significantly improved over the last years, says Giordano, they always carry risks, such as an allergic reaction to anesthesia, bleeding in the brain, infection at the wound site, blood clots, even coma. Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS), a technology currently being developed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), could potentially tackle this. Patients could wear a cap, helmet, or visor that transmits electrical signals from the brain to a computer system and back, in a brain-computer interface that would not need surgery.

“This could counter the implantation of hardware into the brain and body, around which there is also a lot of public hesitance,” says Giordano, who is working on such techniques at DARPA.

Embedding a chip in your head is one of the finest examples of biohacking, an umbrella word for all the practices aimed at hacking one’s body and brain to enhance performance –a citizen do-it-yourself biology. It is also a word charged enough to set off a public backlash. Large segments of the population will simply refuse to allow that level of invasiveness in their heads, says Laura Cabrera, an associate professor of neuroethics at the Center for Neural Engineering, Department of Engineering Science and Mechanics at Penn State University. Cabrera urges caution when it comes to DBS’s potential.

“We've been using it for Parkinson's for over two decades, hoping that now that they get DBS, patients will get off medications. But people have continued taking their drugs, even increasing them,” she says. What the UCSF found is a proof of concept that DBS worked in one depressed person, but there’s a long way ahead until we can confidently say this finding is generalizable to a large group of patients. Besides, as a society, we are not there yet, says Cabrera. “Most people, at least in my research, say they don't want to have things in their brain,” she says. But what could really go wrong if we biohacked our own brains anyway?

In 2014, a man who had received a deep brain implant for a movement disorder started developing an affection for Johnny Cash’s music when he had previously been an avid country music fan. Many protested that the chip had tampered with his personality. Could sparking the brain with electricity generated by a chip outside it put an end to our individuality, messing with our musical preferences, unique quirks, our deeper sense of ego?

“What we found is that when you stimulate a region, you affect people’s moods, their energies,” says Krystal. You are neither changing their personality nor creating creatures of eternal happiness, he says. “’Being on a phone call would generally be a setting that would normally trigger symptoms of depression in me,’” Krystal reports his patient telling him. ‘I now know bad things happen, but am not affected by them in the same way. They don’t trigger the depression.’” Of the research, Krystal continues: “We are not trying to take away normal responses to the world. We are just trying to eliminate this one thing, which is depression, which impedes patients’ ability to function and deal with normal stuff.”

Yet even change itself shouldn't be seen as threatening, especially if the patient had probably desired it in the first place. “The intent of therapy in psychiatric disorders is to change the personality, because a psychiatric disorder by definition is a disorder of personality,” says Cabrera. A person in therapy wants to restore the lost sense of “normal self”. And as for this restoration altering your original taste in music, Cabrera says we are talking about rarities, extremely scarce phenomena that are possible with medication as well.

Maybe it is the allure of dystopian sci-fi films: people have a tendency to worry about dark forces that will spread malice across the world when the line between human and machine has blurred. Such mind-control through DBS would probably require a decent leap of logic with the tools science has--at least to this day. “This would require an understanding of the parameters of brain stimulation we still don't have,” says Cabrera. Still, brain implants are not fully corrupt-proof.

“Hackers could shut off the device or change the parameters of the patient's neurological function enhancing symptoms or creating harmful side-effects,” says Giordano.

There are risks, but also failsafe ways to tackle them, adds Anderson. “Just like medications are not permanent, we could ensure the implants are used for a specific period of time,” he says. And just like people go in for checkups when they are under medication, they could periodically get their personal brain implants checked to see if they have been altered or not, he continues. “It is what my research group refers to as biosecurity by design,” says Giordano. “It is important that we proactively design systems that cannot be corrupted.”

Two weeks after receiving the implant, Sarah scored 14 out of 54 on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, a ten-item questionnaire psychiatrists use to measure the severity of depressive episodes. She had initially scored 36. Today she scores under 10. She would have had to wait between four and eight weeks to see positive results had she taken the antidepressant road, says Krystal.

He and his team have enrolled two other patients in the trials and hope to add nine more. They already have some preliminary evidence that there's another place that works better in the brain of another patient, because that specific patient had been experiencing more anxiety as opposed to despondency. Almost certainly, we will have different biomarkers for different people, and brain stimulation will be tailored to a person’s unique situation, says Krystal. “Each brain is different, just like each face is different.”

Researchers Are Discovering How to Predict – and Maybe Treat — Pregnancy Complications Early On.

Katie Love cradles her newborn daughter, born after a bout with preeclampsia.

Katie Love wishes there was some way she could have been prepared. But there was no way to know, early in 2020, that her pregnancy would lead to terrifyingly high blood pressure and multiple hospital visits, ending in induced labor and a 56-hour-long, “nightmare” delivery at 37 weeks. Love, a social media strategist in Pittsburgh, had preeclampsia, a poorly understood and potentially deadly pregnancy complication that affects 1 in 25 pregnant women in the United States. But there was no blood test, no easy diagnostic marker to warn Love that this might happen. Even on her first visit to the emergency room, with sky-high blood pressure, doctors could not be certain preeclampsia was the cause.

In fact, the primary but imperfect indicators for preeclampsia — high blood pressure and protein in the urine — haven’t changed in decades. The Preeclampsia Foundation calls a simple, rapid test to predict or diagnose the condition “a key component needed in the fight.”

Another common pregnancy complication is preterm birth, which affects 1 in 10 U.S. pregnancies, but there are few options to predict that might happen, either.

“The best tool that obstetricians have at the moment is still a tape measure and a blood pressure cuff to diagnose whatever’s happening in your pregnancy,” says Fiona Kaper, a vice president at the DNA-sequencing company Illumina in San Diego.

The hunt for such specific biomarkers is now taking off, at Illumina and elsewhere, as scientists probe maternal blood for signs that could herald pregnancy problems. These same molecules offer clues that might lead to more specific treatments. So far, it’s clear that many complications start with the placenta, the temporary organ that transfers nutrients, oxygen and waste between mother and fetus, and that these problems often start well before symptoms arise. Researchers are using the latest stem-cell technology to better understand the causes of complications and test treatments.

Pressing Need

Obstetricians aren’t flying completely blind; medical history can point to high or low risk for pregnancy complications. But ultimately, “everybody who’s pregnant is at risk for preeclampsia,” says Sarosh Rana, chief of maternal-fetal medicine at University of Chicago Medicine and an advisor to the Preeclampsia Foundation. And the symptoms of the condition include problems like headache and swollen feet that overlap with those of pregnancy in general, complicating diagnoses.

The “holy grail" would be early, first-trimester biomarkers. If obstetricians and expecting parents could know, in the first few months of pregnancy, that preeclampsia is a risk, a pregnant woman could monitor her blood pressure at home and take-low dose aspirin that might stave it off.

There are a couple more direct tests physicians can turn to, but these are imperfect. For preterm labor, fetal fibronectin makes up a sort of glue that keeps the amniotic sac, which cushions the unborn baby, attached to the uterus. If it’s not present near a woman’s cervix, that’s a good indicator that she’s not in labor, and can be safely sent home, says Lauren Demosthenes, an obstetrician and senior medical director of the digital health company Babyscripts in Washington, D.C. But if fibronectin appears, it might or might not indicate preterm labor.

“What we want is a test that gives us a positive predictive [signal],” says Demosthenes. “I want to know, if I get it, is it really going to predict preterm birth, or is it just going to make us worry more and order more tests?” In fact, the fetal fibronectin test hasn’t been shown to improve pregnancy outcomes, and Demosthenes says it’s fallen out of favor in many clinics.

Similarly, there’s a blood test, based on the ratio of the amounts of two different proteins, that can rule out preeclampsia but not confirm it’s happening. It’s approved in many countries, though not the U.S.; studies are still ongoing. A positive test, which means “maybe preeclampsia,” still leaves doctors and parents-to-be facing excruciating decisions: If the mother’s life is in danger, delivering the baby can save her, but even a few more days in the uterus can promote the baby’s health. In Ireland, where the test is available, it’s not getting much use, says Patricia Maguire, director of the University College Dublin Institute for Discovery.

Maguire has identified proteins released by platelets that indicate pregnancy — the “most expensive pregnancy test in the world,” she jokes. She is now testing those markers in women with suspected preeclampsia.

The “holy grail,” says Maguire, would be early, first-trimester biomarkers. If obstetricians and expecting parents could know, in the first few months of pregnancy, that preeclampsia is a risk, a pregnant woman could monitor her blood pressure at home and take-low dose aspirin that might stave it off. Similarly, if a quick blood test indicated that preterm labor could happen, doctors could take further steps such as measuring the cervix and prescribing progesterone if it’s on the short side.

Biomarkers in Blood

It was fatherhood that drew Stephen Quake, a biophysicist at Stanford University in California, to the study of pregnancy biomarkers. His wife, pregnant with their first child in 2001, had a test called amniocentesis. That involves extracting a sample from within the uterus, using a 3–8-inch-long needle, for genetic testing. The test can identify genetic differences, such as Down syndrome, but also carries risks including miscarriage or infection. In this case, mom and baby were fine (Quake’s daughter is now a college student), but he found the diagnostic danger unacceptable.

Seeking a less invasive test, Quake in 2008 reported that there’s enough fetal DNA in the maternal bloodstream to diagnose Down syndrome and other genetic conditions. “Use of amniocentesis has plunged,” he says.

Then, recalling that his daughter was born three and a half weeks before her due date — and that Quake’s own mom claims he was a month late, which makes him think the due date must have been off — he started researching markers that could accurately assess a fetus’ age and predict the timing of labor. In this case, Quake was interested in RNA, not DNA, because it’s a signal of which genes the fetus’, placenta’s, and mother’s tissues are using to create proteins. Specifically, these are RNAs that have exited the cells that made them. Tissues can use such free RNAs as messages, wrapping them in membranous envelopes to travel the bloodstream to other body parts. Dying cells also release fragments containing RNAs. “A lot of information is in there,” says Kaper.

In a small study of 31 healthy pregnant women, published in 2018, Quake and collaborators discovered nine RNAs that could predict gestational age, which indicates due date, just as well as ultrasound. With another set of 38 women, including 13 who delivered early, the researchers discovered seven RNAs that predicted preterm labor up to two months in advance.

Quake notes that an RNA-based blood test is cheaper and more portable than ultrasound, so it might be useful in the developing world. A company he cofounded, Mirvie, Inc., is now analyzing RNA’s predictive value further, in thousands of diverse women. CEO and cofounder Maneesh Jain says that since preterm labor is so poorly understood, they’re sequencing RNAs that represent about 20,000 genes — essentially all the genes humans have — to find the very best biomarkers. “We don’t know enough about this field to guess what it might be,” he says. “We feel we’ve got to cast the net wide.”

Quake, and Mirvie, are now working on biomarkers for preeclampsia. In a recent preprint study, not yet reviewed by other experts, Quake’s Stanford team reported 18 RNAs that, measured before 16 weeks, correctly predicted preeclampsia 56–100% of the time.

Other researchers are taking a similar tack. Kaper’s team at Illumina was able to classify preeclampsia from bloodstream RNAs with 85 to 89% accuracy, though they didn’t attempt to predict it. And Louise Laurent, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and researcher at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has defined several pairs of microRNAs — pint-sized RNAs that regulate other ones — in second-trimester blood samples that predict preeclampsia later on.

Placentas in a Dish

The RNAs that show up in these studies often come from genes used by the placenta. But they’re only signals that something’s wrong, not necessarily the root cause. “There still is not much known about what really causes major complications of pregnancy,” says Laurent.

The challenge is that placental problems likely occur early on, as the organ forms in the first trimester. For example, if the placenta did a poor job of building blood vessels through the uterine lining, it might cause preeclampsia later as the growing fetus tries to access more and more blood through insufficient vessels, leading to high blood pressure in the mother. “Everyone has kind of suspected that that is probably what goes wrong,” says Mana Parast, a pathologist and researcher at UCSD.

To see how a placenta first faltered, “you want to go back in time,” says Parast. It’s only recently become possible to do something akin to that: She and Laurent take cells from the umbilical cord (which is a genetic match for the placenta) at the end of pregnancy, and turn them into stem cells, which can become any kind of cell. They then nudge those stem cells to make new placenta cells in lab dishes. But when the researchers start with cells from an umbilical cord after preeclampsia, they find the stem cells struggle to even form proper placenta cells, or they develop abnormally. So yes, something seems to go wrong right at the beginning. Now, the team plans to use these cell cultures to study the microRNAs that indicate preeclampsia risk, and to look for medications that might reverse the problems, Parast says.

Biomarkers could lead to treatments. For example, one of the proteins that commercial preeclampsia diagnostic kits test for is called soluble Flt-1. It’s a sort of anti-growth factor, explains Rana, that can cause problems with blood vessels and thus high blood pressure. Getting rid of the extra Flt-1, then, might alleviate symptoms and keep the mother safe, giving the baby more time to develop. Indeed, a small trial that filtered this protein from the blood did lower blood pressure, allowing participants to keep their babies inside for a couple of weeks longer, researchers reported in 2011.

For pregnant women like Love, even advance warning would have been beneficial. Laurent and others envision a first-trimester blood test that would use different kinds of biomolecules — RNAs, proteins, whatever works best — to indicate whether a pregnancy is at low, medium, or high risk for common complications.

“I prefer to be prepared,” says Love, now the mother of a healthy little girl. “I just wouldn’t have been so thrown off by the whole thing.”