Scientists make progress with growing organs for transplants

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have laid the foundations for growing synthetic embryos that could develop a beating heart, gut and brain.

Story by Big Think

For over a century, scientists have dreamed of growing human organs sans humans. This technology could put an end to the scarcity of organs for transplants. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The capability to grow fully functional organs would revolutionize research. For example, scientists could observe mysterious biological processes, such as how human cells and organs develop a disease and respond (or fail to respond) to medication without involving human subjects.

Recently, a team of researchers from the University of Cambridge has laid the foundations not just for growing functional organs but functional synthetic embryos capable of developing a beating heart, gut, and brain. Their report was published in Nature.

The organoid revolution

In 1981, scientists discovered how to keep stem cells alive. This was a significant breakthrough, as stem cells have notoriously rigorous demands. Nevertheless, stem cells remained a relatively niche research area, mainly because scientists didn’t know how to convince the cells to turn into other cells.

Then, in 1987, scientists embedded isolated stem cells in a gelatinous protein mixture called Matrigel, which simulated the three-dimensional environment of animal tissue. The cells thrived, but they also did something remarkable: they created breast tissue capable of producing milk proteins. This was the first organoid — a clump of cells that behave and function like a real organ. The organoid revolution had begun, and it all started with a boob in Jello.

For the next 20 years, it was rare to find a scientist who identified as an “organoid researcher,” but there were many “stem cell researchers” who wanted to figure out how to turn stem cells into other cells. Eventually, they discovered the signals (called growth factors) that stem cells require to differentiate into other types of cells.

For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells.

By the end of the 2000s, researchers began combining stem cells, Matrigel, and the newly characterized growth factors to create dozens of organoids, from liver organoids capable of producing the bile salts necessary for digesting fat to brain organoids with components that resemble eyes, the spinal cord, and arguably, the beginnings of sentience.

Synthetic embryos

Organoids possess an intrinsic flaw: they are organ-like. They share some characteristics with real organs, making them powerful tools for research. However, no one has found a way to create an organoid with all the characteristics and functions of a real organ. But Magdalena Żernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist, might have set the foundation for that discovery.

Żernicka-Goetz hypothesized that organoids fail to develop into fully functional organs because organs develop as a collective. Organoid research often uses embryonic stem cells, which are the cells from which the developing organism is created. However, there are two other types of stem cells in an early embryo: stem cells that become the placenta and those that become the yolk sac (where the embryo grows and gets its nutrients in early development). For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells. In other words, Żernicka-Goetz suspected the best way to grow a functional organoid was to produce a synthetic embryoid.

As described in the aforementioned Nature paper, Żernicka-Goetz and her team mimicked the embryonic environment by mixing these three types of stem cells from mice. Amazingly, the stem cells self-organized into structures and progressed through the successive developmental stages until they had beating hearts and the foundations of the brain.

“Our mouse embryo model not only develops a brain, but also a beating heart [and] all the components that go on to make up the body,” said Żernicka-Goetz. “It’s just unbelievable that we’ve got this far. This has been the dream of our community for years and major focus of our work for a decade and finally we’ve done it.”

If the methods developed by Żernicka-Goetz’s team are successful with human stem cells, scientists someday could use them to guide the development of synthetic organs for patients awaiting transplants. It also opens the door to studying how embryos develop during pregnancy.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy could treat Long COVID, new study shows

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been used in the past to help people with traumatic brain injury, stroke and other conditions involving wounds to the brain. Now, researchers at Shamir Medical Center in Tel Aviv are studying how it could treat Long Covid.

Long COVID is not a single disease, it is a syndrome or cluster of symptoms that can arise from exposure to SARS-CoV-2, a virus that affects an unusually large number of different tissue types. That's because the ACE2 receptor it uses to enter cells is common throughout the body, and inflammation from the immune response fighting that infection can damage surrounding tissue.

One of the most widely shared groups of symptoms is fatigue and what has come to be called “brain fog,” a difficulty focusing and an amorphous feeling of slowed mental functioning and capacity. Researchers have tied these COVID-related symptoms to tissue damage in specific sections of the brain and actual shrinkage in its size.

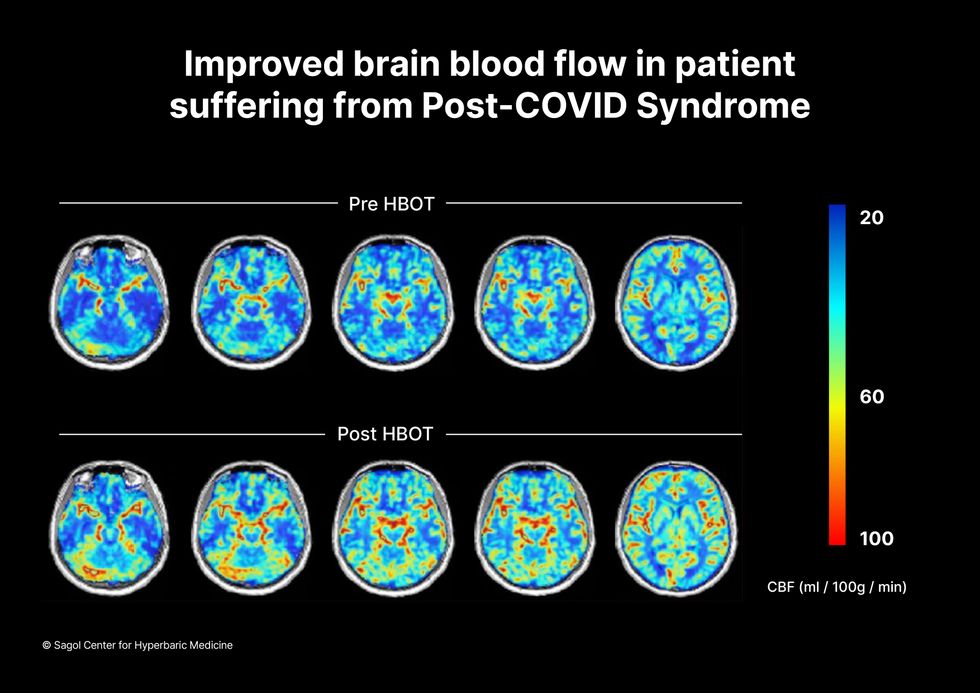

When Shai Efrati, medical director of the Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Research in Tel Aviv, first looked at functional magnetic resonance images (fMRIs) of patients with what is now called long COVID, he saw “micro infarcts along the brain.” It reminded him of similar lesions in other conditions he had treated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). “Once we saw that, we said, this is the type of wound we can treat. It doesn't matter if the primary cause is mechanical injury like TBI [traumatic brain injury] or stroke … we know how to oxidize them.”Efrati came to HBOT almost by accident. The physician had seen how it had helped heal diabetic ulcers and improved the lives of other patients, but he was busy with his own research. Then the director of his Tel Aviv hospital threatened to shut down the small HBOT chamber unless Efrati took on administrative responsibility for it. He reluctantly agreed, a decision that shifted the entire focus of his research.

“The main difference between wounds in the leg and wounds in the brain is that one is something we can see, it's tangible, and the wound in the brain is hidden,” says Efrati. With fMRIs, he can measure how a limited supply of oxygen in blood is shuttled around to fuel activity in various parts of the brain. Years of research have mapped how specific areas of the brain control activity ranging from thinking to moving. An fMRI captures the brain area as it’s activated by supplies of oxygen; lack of activity after the same stimuli suggests damage has occurred in that tissue. Suddenly, what was hidden became visible to researchers using fMRI. It helped to make a diagnosis and measure response to treatment.

HBOT is not a single thing but rather a tool, a process or approach with variations depending on the condition being treated. It aims to increase the amount of oxygen that gets to damaged tissue and speed up healing. Regular air is about 21 percent oxygen. But inside the HBOT chamber the atmospheric pressure can be increased to up to three times normal pressure at sea level and the patient breathes pure oxygen through a mask; blood becomes saturated with much higher levels of oxygen. This can defuse through the damaged capillaries of a wound and promote healing.

The trial

Efrati’s clinical trials started in December 2020, barely a year after SARS-CoV-2 had first appeared in Israel. Patients who’d experienced cognitive issues after having COVID received 40 sessions in the chamber over a period of 60 days. In each session, they spent 90 minutes breathing through a mask at two atmospheres of pressure. While inside, they performed mental exercises to train the brain. The only difference between the two groups of patients was that one breathed pure oxygen while the other group breathed normal air. No one knew who was receiving which level of oxygen.

The results were striking. Before and after fMRIs showed significant repair of damaged tissue in the brain and functional cognition tests improved substantially among those who received pure oxygen. Importantly, 80 percent of patients said they felt back to “normal,” but Efrati says they didn't include patient evaluation in the paper because there was no baseline data to show how they functioned before COVID. After the study was completed, the placebo group was offered a new round of treatments using 100 percent oxygen, and the team saw similar results.

Scans show improved blood flow in a patient suffering from Long Covid.

Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine

Efrati's use of HBOT is part of an emerging geroscience approach to diseases associated with aging. These researchers see systems dysfunctions that are common to several diseases, such as inflammation, which has been shown to play a role in micro infarcts, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Preliminary research suggests that HBOT can retard some underlying mechanisms of aging, which might address several medical conditions. However, the drug approval process is set up to regulate individual disease, not conditions as broad as aging, and so they concentrate on treating the low hanging fruit: disorders where effective treatments currently are limited and success might be demonstrated.

The key to HBOT's effectiveness is something called the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox where a body does not react to an increase in available oxygen, only to a decrease, regardless of the starting point. That danger signal has a powerful effect on gene expression, resulting in changes in metabolism, and the proliferation of stem cells. That occurs with each cycle of 20 minutes of pure oxygen followed by 5 minutes of regular air circulating through the masks, while the chamber remains pressurized. The high levels of oxygen in the blood provide the fuel necessary for tissue regeneration.

The hyperbaric chamber that Efrati has built can hold a dozen patients and attending medical staff. Think of it as a pressurized airplane cabin, only with much more space than even in first class. In the U.S., people think of HBOT as “a sack of air or some tube that you can buy on Amazon” or find at a health spa. “That is total bullshit,” Efrati says. “It has to be a medical class center where a physician can lose their license if they are not operating it properly.”

Shai Efrati

Alexander Charney, a research psychiatrist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, calls Efrati’s study thoughtful and well designed. But it demands a lot from patients with its intense number of sessions. Those types of regimens have proven difficult to roll out to large numbers of patients. Still, the results are intriguing enough to merit additional trials.

John J. Miller, a physician and editor in chief of Psychiatric Times, has seen “many physicians that use hyperbaric oxygen for various brain disorders such as TBI.” He is intrigued by Efrati's work and believes the approach “has great potential to help patients with long COVID whose symptoms are related to brain tissue changes.”

Efrati believes so much in the power of the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox to heal a variety of tissue injuries that he is leading the medical advisory board at Aviv Clinic, an international network of clinics that are delivering HBOT treatments based on research conducted in Israel. His goal is to silence doubters by quickly opening about 50 such clinics worldwide, based on the model of standalone dialysis clinics in the United States. Sagol Center is treating 300 patients per day, and clinics have opened in Florida and Dubai. There are plans to open another in Manhattan.

A blood test may catch colorectal cancer before it's too late

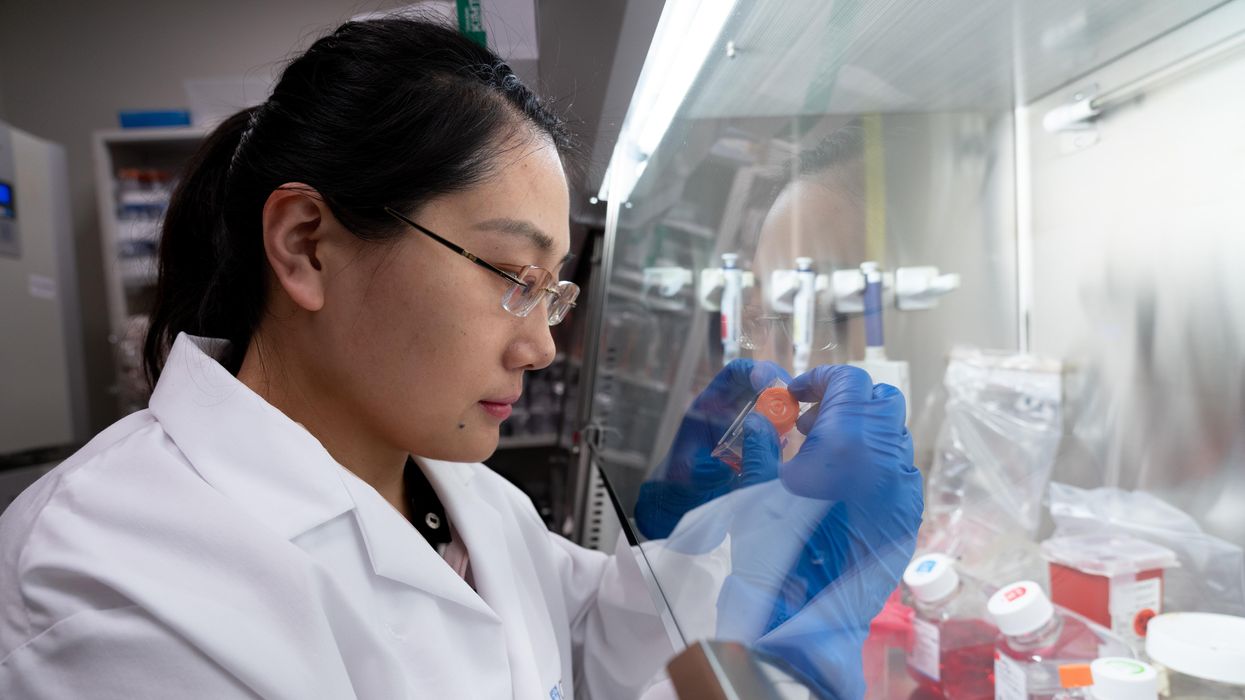

A scientist works on a blood test in the Ajay Goel Lab, one of many labs that are developing blood tests to screen for different types of cancer.

Soon it may be possible to find different types of cancer earlier than ever through a simple blood test.

Among the many blood tests in development, researchers announced in July that they have developed one that may screen for early-onset colorectal cancer. The new potential screening tool, detailed in a study in the journal Gastroenterology, represents a major step in noninvasively and inexpensively detecting nonhereditary colorectal cancer at an earlier and more treatable stage.

In recent years, this type of cancer has been on the upswing in adults under age 50 and in those without a family history. In 2021, the American Cancer Society's revised guidelines began recommending that colorectal cancer screenings with colonoscopy begin at age 45. But that still wouldn’t catch many early-onset cases among people in their 20s and 30s, says Ajay Goel, professor and chair of molecular diagnostics and experimental therapeutics at City of Hope, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit cancer research and treatment center that developed the new blood test.

“These people will mostly be missed because they will never be screened for it,” Goel says. Overall, colorectal cancer is the fourth most common malignancy, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Goel is far from the only one working on this. Dozens of companies are in the process of developing blood tests to screen for different types of malignancies.

Some estimates indicate that between one-fourth and one-third of all newly diagnosed colorectal cancers are early-onset. These patients generally present with more aggressive and advanced disease at diagnosis compared to late-onset colorectal cancer detected in people 50 years or older.

To develop his test, Goel examined publicly available datasets and figured out that changes in novel microRNAs, or miRNAs, which regulate the expression of genes, occurred in people with early-onset colorectal cancer. He confirmed these biomarkers by looking for them in the blood of 149 patients who had the early-onset form of the disease. In particular, Goel and his team of researchers were able to pick out four miRNAs that serve as a telltale sign of this cancer when they’re found in combination with each other.

The blood test is being validated by following another group of patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. “We have filed for intellectual property on this invention and are currently seeking biotech/pharma partners to license and commercialize this invention,” Goel says.

He’s far from the only one working on this. Dozens of companies are in the process of developing blood tests to screen for different types of malignancies, says Timothy Rebbeck, a professor of cancer prevention at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. But, he adds, “It’s still very early, and the technology still needs a lot of work before it will revolutionize early detection.”

The accuracy of the early detection blood tests for cancer isn’t yet where researchers would like it to be. To use these tests widely in people without cancer, a very high degree of precision is needed, says David VanderWeele, interim director of the OncoSET Molecular Tumor Board at Northwestern University’s Lurie Cancer Center in Chicago.

Otherwise, “you’re going to cause a lot of anxiety unnecessarily if people have false-positive tests,” VanderWeele says. So far, “these tests are better at finding cancer when there’s a higher burden of cancer present,” although the goal is to detect cancer at the earliest stages. Even so, “we are making progress,” he adds.

While early detection is known to improve outcomes, most cancers are detected too late, often after they metastasize and people develop symptoms. Only five cancer types have recommended standard screenings, none of which involve blood tests—breast, cervical, colorectal, lung (smokers considered at risk) and prostate cancers, says Trish Rowland, vice president of corporate communications at GRAIL, a biotechnology company in Menlo Park, Calif., which developed a multi-cancer early detection blood test.

These recommended screenings check for individual cancers rather than looking for any form of cancer someone may have. The devil lies in the fact that cancers without widespread screening recommendations represent the vast majority of cancer diagnoses and most cancer deaths.

GRAIL’s Galleri multi-cancer early detection test is designed to find more cancers at earlier stages by analyzing DNA shed into the bloodstream by cells—with as few false positives as possible, she says. The test is currently available by prescription only for those with an elevated risk of cancer. Consumers can request it from their healthcare or telemedicine provider. “Galleri can detect a shared cancer signal across more than 50 types of cancers through a simple blood draw,” Rowland says, adding that it can be integrated into annual health checks and routine blood work.

Cancer patients—even those with early and curable disease—often have tumor cells circulating in their blood. “These tumor cells act as a biomarker and can be used for cancer detection and diagnosis,” says Andrew Wang, a radiation oncologist and professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “Our research goal is to be able to detect these tumor cells to help with cancer management.” Collaborating with Seungpyo Hong, the Milton J. Henrichs Chair and Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy, “we have developed a highly sensitive assay to capture these circulating tumor cells.”

Even if the quality of a blood test is superior, finding cancer early doesn’t always mean it’s absolutely best to treat it. For example, prostate cancer treatment’s potential side effects—the inability to control urine or have sex—may be worse than living with a slow-growing tumor that is unlikely to be fatal. “[The test] needs to tell me, am I going to die of that cancer? And, if I intervene, will I live longer?” says John Marshall, chief of hematology and oncology at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Ajay Goel Lab

A blood test developed at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston helps predict who may benefit from lung cancer screening when it is combined with a risk model based on an individual’s smoking history, according to a study published in January in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The personalized lung cancer risk assessment was more sensitive and specific than the 2021 and 2013 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force criteria.

The study involved participants from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial with a minimum of a 10 pack-year smoking history, meaning they smoked 20 cigarettes per day for ten years. If implemented, the blood test plus model would have found 9.2 percent more lung cancer cases for screening and decreased referral to screening among non-cases by 13.7 percent compared to the 2021 task force criteria, according to Oncology Times.

The conventional type of screening for lung cancer is an annual low-dose CT scan, but only a small percentage of people who are eligible will actually get these scans, says Sam Hanash, professor of clinical cancer prevention and director of MD Anderson’s Center for Global Cancer Early Detection. Such screening is not readily available in most countries.

In methodically searching for blood-based biomarkers for lung cancer screening, MD Anderson researchers developed a simple test consisting of four proteins. These proteins circulating in the blood were at high levels in individuals who had lung cancer or later developed it, Hanash says.

“The interest in blood tests for cancer early detection has skyrocketed in the past few years,” he notes, “due in part to advances in technology and a better understanding of cancer causation, cancer drivers and molecular changes that occur with cancer development.”

However, at the present time, none of the blood tests being considered eliminate the need for screening of eligible subjects using established methods, such as colonoscopy for colorectal cancer. Yet, Hanash says, “they have the potential to complement these modalities.”