Over 1 Million Seeds Are Buried Near the North Pole to Back Up the World’s Crops

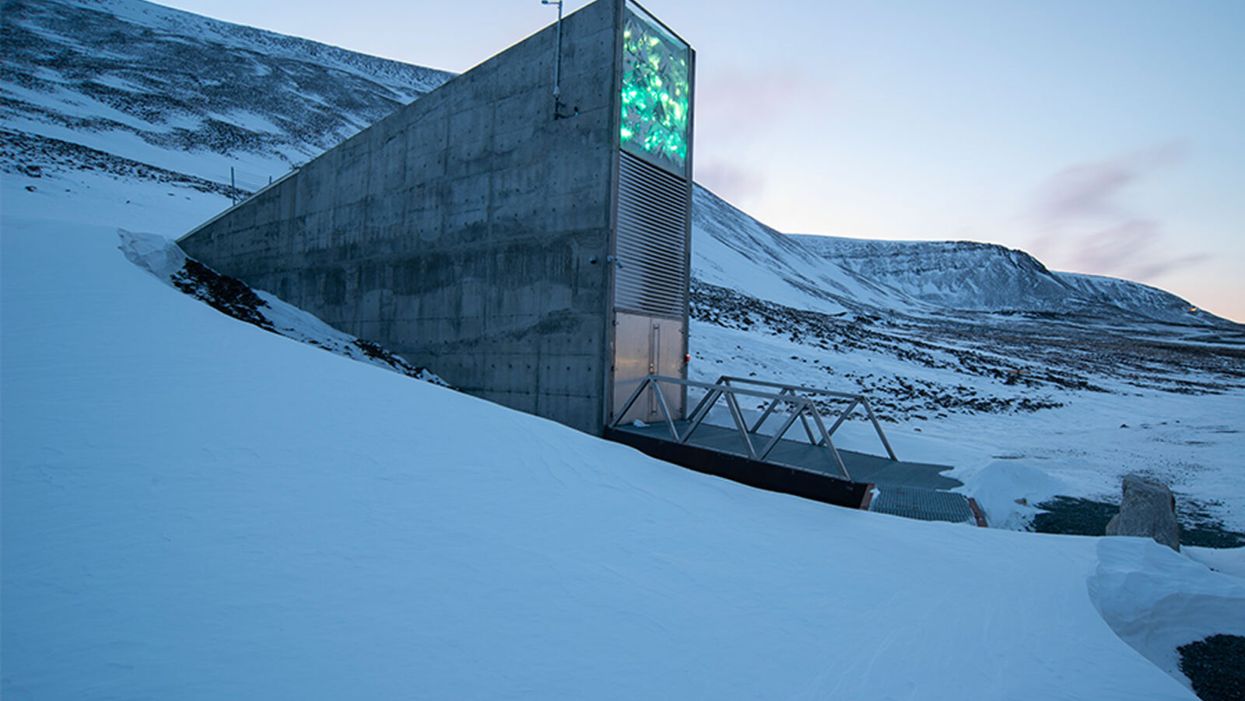

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault preserves more than one million of the world's seeds deep inside Platäfjellet Mountain.

The impressive structure protrudes from the side of a snowy mountain on the Svalbard Archipelago, a cluster of islands about halfway between Norway and the North Pole.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost. We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

Art installations on the building's rooftop and front façade glimmer like diamonds in the polar night, but it is what lies buried deep inside the frozen rock, 475 feet from the building's entrance, that is most precious. Here, in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, are backup copies of more than a million of the world's agricultural seeds.

Inside the vault, seed boxes from many gene banks and many countries. "The seeds don't know national boundaries," says Kent Nnadozie, the UN's Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

(Photo credit: Svalbard Global Seed Vault/Riccardo Gangale)

The Svalbard vault -- which has been called the Doomsday Vault, or a Noah's Ark for seeds -- preserves the genetic materials of more than 6000 crop species and their wild relatives, including many of the varieties within those species. Svalbard's collection represents all the traits that will enable the plants that feed the world to adapt – with the help of farmers and plant breeders – to rapidly changing climactic conditions, including rising temperatures, more intense drought, and increasing soil salinity. "We save these seeds because we want to ensure food security for future generations," says Grethe Helene Evjen, Senior Advisor at the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food .

A recent study in the journal Nature predicted that global warming could cause catastrophic losses of biodiversity in regions across the globe throughout this century. Yet global warming also threatens the permafrost that surrounds the seed vault, the very thing that was once considered a failsafe means of keeping these seeds frozen and safeguarding the diversity of our crops. In fact, record temperatures in Svalbard a few years ago – and a significant breach of water into the access tunnel to the vault -- prompted the Norwegian government to invest $20 million euros on improvements at the facility to further secure the genetic resources locked inside. The hope: that technology can work in concert with nature's freezer to keep the world's seeds viable.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost," says Hege Njaa Aschim, a spokesperson for Statsbygg, the government agency that recently completed the upgrades at the seed vault. "We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

The Apex of the Global Conservation System

More than 1700 genebanks around the globe preserve the diverse seed varieties from their regions. They range from small community seed banks in developing countries, where small farmers save and trade their seeds with growers in nearby villages, to specialized university collections, to national and international genetic resource repositories. But many of these facilities are vulnerable to war, natural disasters, or even lack of funding.

"If anything should happen to the resources in a regular genebank, Svalbard is the backup – it's essentially the apex of the global conservation system," says Kent Nnadozie, Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture at the United Nations, who likens the Global Vault to the Central Reserve Bank. "You have regular banks that do active trading, but the Central Bank is the final reserve where the banks store their gold deposits."

Similarly, farmers deposit their seeds in regional genebanks, and also look to these banks for new varieties to help their crops adapt to, say, increasing temperatures, or resist intrusive pests. Regional banks, in turn, store duplicates from their collections at Svalbard. These seeds remain the sovereign property of the country or institution depositing them; only they can "make a withdrawal."

The Global Vault has already proven invaluable: The International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), formerly located outside of Aleppo, Syria, held more than 140,000 seed samples, including plants that were extinct in their natural habitats, before the Syrian Crisis in 2012. Fortunately, they had managed to back up most of their seed samples at Svalbard before they were forced to relocate to Lebanon and Morocco. In 2017, ICARDA became the first – and only – organization to withdraw their stored seeds. They have now regenerated almost all of the samples at their new locations and recently redeposited new seeds for safekeeping at Svalbard.

Rapid Global Warming Threatens Permafrost

The Global Vault, a joint venture between the Norwegian government, the Crop Trust and the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre (NordGen) that started operating in 2008, was sited in Svalbard in part because of its remote yet accessible location: Svalbard is the northernmost inhabited spot on Earth with an airport. But experts also thought it a failsafe choice for long-term seed storage because its permafrost would offer natural freezing – even if cooling systems were to fail. No one imagined that the permafrost could fail.

"We've had record temperatures in the region recently, and there are a lot of signs that global warming is happening faster at the extreme latitudes," says Geoff Hawtin, a world-renowned authority in plant conservation, who is the founding director of -- and now advisor to -- the Crop Trust. "Svalbard is still arguably one of the safest places for the seeds from a temperature point of view, but it's actually not going to be as cold as we thought 20 years ago."

A recent report by the Norwegian Centre for Climate Services predicted that Svalbard could become 50 degrees Fahrenheit warmer by the year 2100. And data from the Norwegian government's environmental monitoring system in Svalbard shows that the permafrost is already thawing: The "active layer," that is, the layer of surface soil that seasonally thaws, has become 25-30 cm thicker since 1998.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization.

Though the permafrost surrounding the seed vault chambers, which are situated well below the active layer, is still intact, the permafrost around the access tunnel never re-established as expected after construction of the Global Vault twelve years ago. As a result, when Svalbard saw record high temperatures and unprecedented rainfall in 2016, about 164 feet of rainwater and snowmelt leaked into the tunnel, turning it into a skating rink and spurring authorities to take what they called a "better safe than sorry approach." They invested in major upgrades to the facility. "The seeds in the vault were never threatened," says Aschim, "but technology has become more important at Svalbard."

Technology Gives Nature a Boost

For now, the permafrost deep inside the mountain still keeps the temperature in the vault down to about -25°F. The cooling systems then give nature a mechanical boost to keep the seed vault chilled even further, to about -64°F, the optimal temperature for conserving seeds. In addition to upgrading to a more effective and sustainable cooling system that runs on CO2, the Norwegian government added backup generators, removed heat-generating electrical equipment from inside the facility to an outside building, installed a thick, watertight door to the vault, and replaced the corrugated steel access tunnel with a cement tunnel that uses the same waterproofing technology as the North Sea oil platforms.

To re-establish the permafrost around the tunnel, they layered cooling pipes with frozen soil around the concrete tunnel, covered the frozen soil with a cooling mat, and topped the cooling mat with the original permafrost soil. They also added drainage ditches on the mountainside to divert meltwater away from the tunnel as the climate gets warmer and wetter.

New Deposits to the Global Vault

The day before COVID-19 arrived in Norway, on February 25th, Prime Minister Erna Solberg hosted the biggest seed-depositing event in the vault's history in honor of the new and improved vault. As snow fell on Svalbard, depositors from almost every continent traveled the windy road from Longyearbyen up Platåfjellet Mountain and braved frigid -8°F weather to celebrate the massive technical upgrades to the facility – and to hand over their seeds.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization, and Israel's University of Haifa, whose deposit included multiple genotypes of wild emmer wheat, an ancient relative of the modern domesticated crop. The storage boxes carried ceremoniously over the threshold that day contained more than 65,000 new seed samples, bringing the total to more than a million, and almost filling the first of three seed chambers in the vault. (The Global Vault can store up to 4.5 million seed samples.)

"Svalbard's samples contain all the possibilities, all the options for the future of our agricultural crops – it's how crops are going to adapt," says Cary Fowler, former executive director of the Crop Trust, who was instrumental in establishing the Global Vault. "If our crops don't adapt to climate change, then neither will we." Dr. Fowler says he is confident that with the recent improvements in the vault, the seeds are going to remain viable for a very long time.

"It's sometimes tempting to get distracted by the romanticism of a seed vault inside a mountain near the North Pole – it's a little bit James Bondish," muses Dr. Fowler. "But the reality is we've essentially put an end to the extinction of more than a million samples of biodiversity forever."

Gene Transfer Leads to Longer Life and Healthspan

In August, a study provided the first proof-of-principle that genetic material transferred from one species to another can increase both longevity and healthspan in the recipient animal.

The naked mole rat won’t win any beauty contests, but it could possibly win in the talent category. Its superpower: fighting the aging process to live several times longer than other animals its size, in a state of youthful vigor.

It’s believed that naked mole rats experience all the normal processes of wear and tear over their lifespan, but that they’re exceptionally good at repairing the damage from oxygen free radicals and the DNA errors that accumulate over time. Even though they possess genes that make them vulnerable to cancer, they rarely develop the disease, or any other age-related disease, for that matter. Naked mole rats are known to live for over 40 years without any signs of aging, whereas mice live on average about two years and are highly prone to cancer.

Now, these remarkable animals may be able to share their superpower with other species. In August, a study provided what may be the first proof-of-principle that genetic material transferred from one species can increase both longevity and healthspan in a recipient animal.

There are several theories to explain the naked mole rat’s longevity, but the one explored in the study, published in Nature, is based on the abundance of large-molecule high-molecular mass hyaluronic acid (HMM-HA).

A small molecule version of hyaluronic acid is commonly added to skin moisturizers and cosmetics that are marketed as ways to keep skin youthful, but this version, just applied to the skin, won’t have a dramatic anti-aging effect. The naked mole rat has an abundance of the much-larger molecule, HMM-HA, in the chemical-rich solution between cells throughout its body. But does the HMM-HA actually govern the extraordinary longevity and healthspan of the naked mole rat?

To answer this question, Dr. Vera Gorbunova, a professor of biology and oncology at the University of Rochester, and her team created a mouse model containing the naked mole rat gene hyaluronic acid synthase 2, or nmrHas2. It turned out that the mice receiving this gene during their early developmental stage also expressed HMM-HA.

The researchers found that the effects of the HMM-HA molecule in the mice were marked and diverse, exceeding the expectations of the study’s co-authors. High-molecular mass hyaluronic acid was more abundant in kidneys, muscles and other organs of the Has2 mice compared to control mice.

In addition, the altered mice had a much lower incidence of cancer. Seventy percent of the control mice eventually developed cancer, compared to only 57 percent of the altered mice, even after several techniques were used to induce the disease. The biggest difference occurred in the oldest mice, where the cancer incidence for the Has2 mice and the controls was 47 percent and 83 percent, respectively.

With regard to longevity, Has2 males increased their lifespan by more than 16 percent and the females added 9 percent. “Somehow the effect is much more pronounced in male mice, and we don’t have a perfect answer as to why,” says Dr. Gorbunova. Another improvement was in the healthspan of the altered mice: the number of years they spent in a state of relative youth. There’s a frailty index for mice, which includes body weight, mobility, grip strength, vision and hearing, in addition to overall conditions such as the health of the coat and body temperature. The Has2 mice scored lower in frailty than the controls by all measures. They also performed better in tests of locomotion and coordination, and in bone density.

Gorbunova’s results show that a gene artificially transferred from one species can have a beneficial effect on another species for longevity, something that had never been demonstrated before. This finding is “quite spectacular,” said Steven Austad, a biologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who was not involved in the study.

Just as in lifespan, the effects in various organs and systems varied between the sexes, a common occurrence in longevity research, according to Austad, who authored the book Methuselah’s Zoo and specializes in the biological differences between species. “We have ten drugs that we can give to mice to make them live longer,” he says, “and all of them work better in one sex than in the other.” This suggests that more attention needs to be paid to the different effects of anti-aging strategies between the sexes, as well as gender differences in healthspan.

According to the study authors, the HMM-HA molecule delivered these benefits by reducing inflammation and senescence (cell dysfunction and death). The molecule also caused a variety of other benefits, including an upregulation of genes involved in the function of mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cells. These mechanisms are implicated in the aging process, and in human disease. In humans, virtually all noncommunicable diseases entail an acceleration of the aging process.

So, would the gene that creates HMM-HA have similar benefits for longevity in humans? “We think about these questions a lot,” Gorbunova says. “It’s been done by injections in certain patients, but it has a local effect in the treatment of organs affected by disease,” which could offer some benefits, she added.

“Mice are very short-lived and cancer-prone, and the effects are small,” says Steven Austad, a biologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “But they did live longer and stay healthy longer, which is remarkable.”

As for a gene therapy to introduce the nmrHas2 gene into humans to obtain a global result, she’s skeptical because of the complexity involved. Gorbunova notes that there are potential dangers in introducing an animal gene into humans, such as immune responses or allergic reactions.

Austad is equally cautious about a gene therapy. “What this study says is that you can take something a species does well and transfer at least some of that into a new species. It opens up the way, but you may need to transfer six or eight or ten genes into a human” to get the large effect desired. Humans are much more complex and contain many more genes than mice, and all systems in a biological organism are intricately connected. One naked mole rat gene may not make a big difference when it interacts with human genes, metabolism and physiology.

Still, Austad thinks the possibilities are tantalizing. “Mice are very short-lived and cancer-prone, and the effects are small,” he says. “But they did live longer and stay healthy longer, which is remarkable.”

As for further research, says Austad, “The first place to look is the skin” to see if the nmrHas2 gene and the HMM-HA it produces can reduce the chance of cancer. Austad added that it would be straightforward to use the gene to try to prevent cancer in skin cells in a dish to see if it prevents cancer. It would not be hard to do. “We don’t know of any downsides to hyaluronic acid in skin, because it’s already used in skin products, and you could look at this fairly quickly.”

“Aging mechanisms evolved over a long time,” says Gorbunova, “so in aging there are multiple mechanisms working together that affect each other.” All of these processes could play a part and almost certainly differ from one species to the next.

“HMM-HA molecules are large, but we’re now looking for a small-molecule drug that would slow it’s breakdown,” she says. “And we’re looking for inhibitors, now being tested in mice, that would hinder the breakdown of hyaluronic acid.” Gorbunova has found a natural, plant-based product that acts as an inhibitor and could potentially be taken as a supplement. Ultimately, though, she thinks that drug development will be the safest and most effective approach to delivering HMM-HA for anti-aging.

A new study provides key insights in what causes Alzheimer's: a breakdown in the brain’s system for clearing waste.

In recent years, researchers of Alzheimer’s have made progress in figuring out the complex factors that lead to the disease. Yet, the root cause, or causes, of Alzheimer’s are still pretty much a mystery.

In fact, many people get Alzheimer’s even though they lack the gene variant we know can play a role in the disease. This is a critical knowledge gap for research to address because the vast majority of Alzheimer’s patients don’t have this variant.

A new study provides key insights into what’s causing the disease. The research, published in Nature Communications, points to a breakdown over time in the brain’s system for clearing waste, an issue that seems to happen in some people as they get older.

Michael Glickman, a biologist at Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, helped lead this research. I asked him to tell me about his approach to studying how this breakdown occurs in the brain, and how he tested a treatment that has potential to fix the problem at its earliest stages.

Dr. Michael Glickman is internationally renowned for his research on the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), the brain's system for clearing the waste that is involved in diseases such as Huntington's, Alzheimer's, and Parkinson's. He is the head of the Lab for Protein Characterization in the Faculty of Biology at the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology. In the lab, Michael and his team focus on protein recycling and the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which protects against serious diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, cystic fibrosis, and diabetes. After earning his PhD at the University of California at Berkeley in 1994, Michael joined the Technion as a Senior Lecturer in 1998 and has served as a full professor since 2009.

Dr. Michael Glickman