Are the gains from gain-of-function research worth the risks?

Gain-of-function research can make pathogens more infectious and deadly. It also enables scientists to prepare remedies in advance.

Scientists have long argued that gain-of-function research, which can make viruses and other infectious agents more contagious or more deadly, was necessary to develop therapies and vaccines to counter the pathogens in case they were used for biological warfare. As the SARS-CoV-2 origins are being investigated, one prominent theory suggests it had leaked from a biolab that conducted gain-of-function research, causing a global pandemic that claimed nearly 6.9 million lives. Now some question the wisdom of engaging in this type of research, stating that the risks may far outweigh the benefits.

“Gain-of-function research means genetically changing a genome in a way that might enhance the biological function of its genes, such as its transmissibility or the range of hosts it can infect,” says George Church, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School. This can occur through direct genetic manipulation as well as by encouraging mutations while growing successive generations of micro-organism in culture. “Some of these changes may impact pathogenesis in a way that is hard to anticipate in advance,” Church says.

In the wake of the global pandemic, the pros and cons of gain-of-function research are being fiercely debated. Some scientists say this type of research is vital for preventing future pandemics or for preparing for bioweapon attacks. Others consider it another disaster waiting to happen. The Government Accounting Office issued a report charging that a framework developed by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) provided inadequate oversight of this potentially deadly research. There’s a movement to stop it altogether. In January, the Viral Gain-of-Function Research Moratorium Act (S. 81) was introduced into the Senate to cease awarding federal research funding to institutions doing gain-of-function studies.

While testifying before the House COVID Origins Select Committee on March 8th, Robert Redfield, former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said that COVID-19 may have resulted from an accidental lab leak involving gain-of-function research. Redfield said his conclusion is based upon the “rapid and high infectivity for human-to-human transmission, which then predicts the rapid evolution of new variants.”

“It is a very, very, very small subset of life science research that could potentially generate a potential pandemic pathogen,” said Gerald Parker, associate dean for Global One Health at Texas A&M University.

“In my opinion,” Redfield continues, “the COVID-19 pandemic presents a case study on the potential dangers of such research. While many believe that gain-of-function research is critical to get ahead of viruses by developing vaccines, in this case, I believe that was the exact opposite.” Consequently, Redfield called for a moratorium on gain-of-function research until there is consensus about the value of such risky science.

What constitutes risky?

The Federal Select Agent Program lists 68 specific infectious agents as risky because they are either very contagious or very deadly. In order to work with these 68 agents, scientists must register with the federal government. Meanwhile, research on deadly pathogens that aren’t easily transmitted, or pathogens that are quite contagious but not deadly, can be conducted without such oversight. “If you’re not working with select agents, you’re not required to register the research with the federal government,” says Gerald Parker, associate dean for Global One Health at Texas A&M University. But the 68-item list may not have everything that could possibly become dangerous or be engineered to be dangerous, thus escaping the government’s scrutiny—an issue that new regulations aim to address.

In January 2017, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) issued additional guidance. It required federal departments and agencies to follow a series of steps when reviewing proposed research that could create, transfer, or use potential pandemic pathogens resulting from the enhancement of a pathogen’s transmissibility or virulence in humans.

In defining risky pathogens, OSTP included viruses that were likely to be highly transmissible and highly virulent, and thus very deadly. The Proposed Biosecurity Oversight Framework for the Future of Science, outlined in 2023, broadened the scope to require federal review of research “that is reasonably anticipated to enhance the transmissibility and/or virulence of any pathogen” likely to pose a threat to public health, health systems or national security. Those types of experiments also include the pathogens’ ability to evade vaccines or therapeutics, or diagnostic detection.

However, Parker says that dangers of generating a pandemic-level germ are tiny. “It is a very, very, very small subset of life science research that could potentially generate a potential pandemic pathogen.” Since gain-of-function guidelines were first issued in 2017, only three such research projects have met those requirements for HHS review. They aimed to study influenza and bird flu. Only two of those projects were funded, according to the NIH Office of Science Policy. For context, NIH funded approximately 11,000 of the 54,000 grant applications it received in 2022.

Guidelines governing gain-of-function research are being strengthened, but Church points out they aren’t ideal yet. “They need to be much clearer about penalties and avoiding positive uses before they would be enforceable.”

What do we gain from gain-of-function research?

The most commonly cited reason to conduct gain-of-function research is for biodefense—the government’s ability to deal with organisms that may pose threats to public health.

In the era of mRNA vaccines, the advance preparedness argument may be even less relevant.

“The need to work with potentially dangerous viruses is central to our preparedness,” Parker says. “It’s essential that we know and understand the basic biology, microbiology, etc. of some of these dangerous pathogens.” That includes increasing our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms by which a virus could become a sustained threat to humans. “Knowing that could help us detect [risks] earlier,” Parker says—and could make it possible to have medical countermeasures, like vaccines and therapeutics, ready.

Most vaccines, however, aren’t affected by this type of research. Essentially, scientists hope they will never need to use it. Moreover, Paul Mango, HSS former deputy chief of staff for policy, and author of the 2022 book Warp Speed, says he believes that in the era of mRNA vaccines, the advance preparedness argument may be even less relevant. “That’s because these vaccines can be developed and produced in less than 12 months, unlike traditional vaccines that require years of development,” he says.

Can better oversight guarantee safety?

Another situation, which Parker calls unnecessarily dangerous, is when regulatory bodies cannot verify that the appropriate biosafety and biosecurity controls are in place.

Gain-of-function studies, Parker points out, are conducted at the basic research level, and they’re performed in high-containment labs. “As long as all the processes, procedures and protocols are followed and there’s appropriate oversight at the institutional and scientific level, it can be conducted safely.”

Globally, there are 69 Biosafety Level 4 (BSL4) labs operating, under construction or being planned, according to recent research from King’s College London and George Mason University for Global BioLabs. Eleven of these 18 high-containment facilities that are planned or under construction are in Asia. Overall, three-quarters of the BSL4 labs are in cities, increasing public health risks if leaks occur.

Researchers say they are confident in the oversight system for BSL4 labs within the U.S. They are less confident in international labs. Global BioLabs’ report concurs. It gives the highest scores for biosafety to industrialized nations, led by France, Australia, Canada, the U.S. and Japan, and the lowest scores to Saudi Arabia, India and some developing African nations. Scores for biosecurity followed similar patterns.

“There are no harmonized international biosafety and biosecurity standards,” Parker notes. That issue has been discussed for at least a decade. Now, in the wake of SARS and the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists and regulators are likely to push for unified oversight standards. “It’s time we got serious about international harmonization of biosafety and biosecurity standards and guidelines,” Parker says. New guidelines are being worked on. The National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) outlined its proposed recommendations in the document titled Proposed Biosecurity Oversight Framework for the Future of Science.

The debates about whether gain-of-function research is useful or poses unnecessary risks to humanity are likely to rage on for a while. The public too has a voice in this debate and should weigh in by communicating with their representatives in government, or by partaking in educational forums or initiatives offered by universities and other institutions. In the meantime, scientists should focus on improving the research regulations, Parker notes. “We need to continue to look for lessons learned and for gaps in our oversight system,” he says. “That’s what we need to do right now.”

How the Human Brain Project Built a Mind of its Own

In 2013, the Human Brain Project set out to build a realistic computer model of the brain over ten years. Now, experts are reflecting on HBP's achievements with an eye toward the future.

In 2009, neuroscientist Henry Markram gave an ambitious TED talk. “Our mission is to build a detailed, realistic computer model of the human brain,” he said, naming three reasons for this unmatched feat of engineering. One was because understanding the human brain was essential to get along in society. Another was because experimenting on animal brains could only get scientists so far in understanding the human ones. Third, medicines for mental disorders weren’t good enough. “There are two billion people on the planet that are affected by mental disorders, and the drugs that are used today are largely empirical,” Markram said. “I think that we can come up with very concrete solutions on how to treat disorders.”

Markram's arguments were very persuasive. In 2013, the European Commission launched the Human Brain Project, or HBP, as part of its Future and Emerging Technologies program. Viewed as Europe’s chance to try to win the “brain race” between the U.S., China, Japan, and other countries, the project received about a billion euros in funding with the goal to simulate the entire human brain on a supercomputer, or in silico, by 2023.

Now, after 10 years of dedicated neuroscience research, the HBP is coming to an end. As its many critics warned, it did not manage to build an entire human brain in silico. Instead, it achieved a multifaceted array of different goals, some of them unexpected.

Scholars have found that the project did help advance neuroscience more than some detractors initially expected, specifically in the area of brain simulations and virtual models. Using an interdisciplinary approach of combining technology, such as AI and digital simulations, with neuroscience, the HBP worked to gain a deeper understanding of the human brain’s complicated structure and functions, which in some cases led to novel treatments for brain disorders. Lastly, through online platforms, the HBP spearheaded a previously unmatched level of global neuroscience collaborations.

Simulating a human brain stirs up controversy

Right from the start, the project was plagued with controversy and condemnation. One of its prominent critics was Yves Fregnac, a professor in cognitive science at the Polytechnic Institute of Paris and research director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research. Fregnac argued in numerous articles that the HBP was overfunded based on proposals with unrealistic goals. “This new way of over-selling scientific targets, deeply aligned with what modern society expects from mega-sciences in the broad sense (big investment, big return), has been observed on several occasions in different scientific sub-fields,” he wrote in one of his articles, “before invading the field of brain sciences and neuromarketing.”

"A human brain model can simulate an experiment a million times for many different conditions, but the actual human experiment can be performed only once or a few times," said Viktor Jirsa, a professor at Aix-Marseille University.

Responding to such critiques, the HBP worked to restructure the effort in its early days with new leadership, organization, and goals that were more flexible and attainable. “The HBP got a more versatile, pluralistic approach,” said Viktor Jirsa, a professor at Aix-Marseille University and one of the HBP lead scientists. He believes that these changes fixed at least some of HBP’s issues. “The project has been on a very productive and scientifically fruitful course since then.”

After restructuring, the HBP became a European hub on brain research, with hundreds of scientists joining its growing network. The HBP created projects focused on various brain topics, from consciousness to neurodegenerative diseases. HBP scientists worked on complex subjects, such as mapping out the brain, combining neuroscience and robotics, and experimenting with neuromorphic computing, a computational technique inspired by the human brain structure and function—to name just a few.

Simulations advance knowledge and treatment options

In 2013, it seemed that bringing neuroscience into a digital age would be farfetched, but research within the HBP has made this achievable. The virtual maps and simulations various HBP teams create through brain imaging data make it easier for neuroscientists to understand brain developments and functions. The teams publish these models on the HBP’s EBRAINS online platform—one of the first to offer access to such data to neuroscientists worldwide via an open-source online site. “This digital infrastructure is backed by high-performance computers, with large datasets and various computational tools,” said Lucy Xiaolu Wang, an assistant professor in the Resource Economics Department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who studies the economics of the HBP. That means it can be used in place of many different types of human experimentation.

Jirsa’s team is one of many within the project that works on virtual brain models and brain simulations. Compiling patient data, Jirsa and his team can create digital simulations of different brain activities—and repeat these experiments many times, which isn’t often possible in surgeries on real brains. “A human brain model can simulate an experiment a million times for many different conditions,” Jirsa explained, “but the actual human experiment can be performed only once or a few times.” Using simulations also saves scientists and doctors time and money when looking at ways to diagnose and treat patients with brain disorders.

Compiling patient data, scientists can create digital simulations of different brain activities—and repeat these experiments many times.

The Human Brain Project

Simulations can help scientists get a full picture that otherwise is unattainable. “Another benefit is data completion,” added Jirsa, “in which incomplete data can be complemented by the model. In clinical settings, we can often measure only certain brain areas, but when linked to the brain model, we can enlarge the range of accessible brain regions and make better diagnostic predictions.”

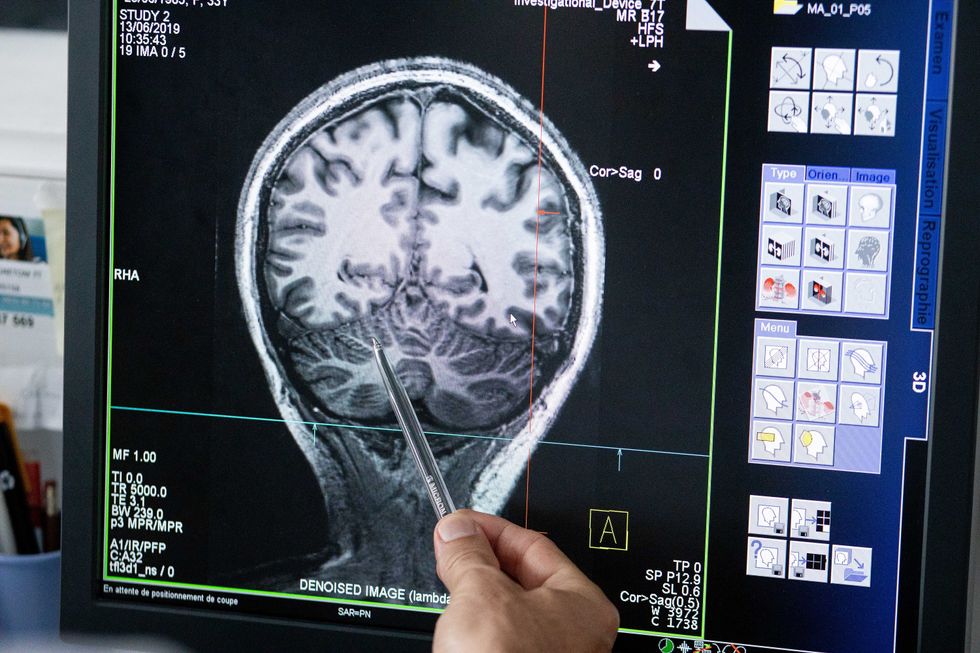

With time, Jirsa’s team was able to move into patient-specific simulations. “We advanced from generic brain models to the ability to use a specific patient’s brain data, from measurements like MRI and others, to create individualized predictive models and simulations,” Jirsa explained. He and his team are working on this personalization technique to treat patients with epilepsy. According to the World Health Organization, about 50 million people worldwide suffer from epilepsy, a disorder that causes recurring seizures. While some epilepsy causes are known others remain an enigma, and many are hard to treat. For some patients whose epilepsy doesn’t respond to medications, removing part of the brain where seizures occur may be the only option. Understanding where in the patients’ brains seizures arise can give scientists a better idea of how to treat them and whether to use surgery versus medications.

“We apply such personalized models…to precisely identify where in a patient’s brain seizures emerge,” Jirsa explained. “This guides individual surgery decisions for patients for which surgery is the only treatment option.” He credits the HBP for the opportunity to develop this novel approach. “The personalization of our epilepsy models was only made possible by the Human Brain Project, in which all the necessary tools have been developed. Without the HBP, the technology would not be in clinical trials today.”

Personalized simulations can significantly advance treatments, predict the outcome of specific medical procedures and optimize them before actually treating patients. Jirsa is watching this happen firsthand in his ongoing research. “Our technology for creating personalized brain models is now used in a large clinical trial for epilepsy, funded by the French state, where we collaborate with clinicians in hospitals,” he explained. “We have also founded a spinoff company called VB Tech (Virtual Brain Technologies) to commercialize our personalized brain model technology and make it available to all patients.”

The Human Brain Project created a level of interconnectedness within the neuroscience research community that never existed before—a network not unlike the brain’s own.

Other experts believe it’s too soon to tell whether brain simulations could change epilepsy treatments. “The life cycle of developing treatments applicable to patients often runs over a decade,” Wang stated. “It is still too early to draw a clear link between HBP’s various project areas with patient care.” However, she admits that some studies built on the HBP-collected knowledge are already showing promise. “Researchers have used neuroscientific atlases and computational tools to develop activity-specific stimulation programs that enabled paraplegic patients to move again in a small-size clinical trial,” Wang said. Another intriguing study looked at simulations of Alzheimer’s in the brain to understand how it evolves over time.

Some challenges remain hard to overcome even with computer simulations. “The major challenge has always been the parameter explosion, which means that many different model parameters can lead to the same result,” Jirsa explained. An example of this parameter explosion could be two different types of neurodegenerative conditions, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases. Both afflict the same area of the brain, the basal ganglia, which can affect movement, but are caused by two different underlying mechanisms. “We face the same situation in the living brain, in which a large range of diverse mechanisms can produce the same behavior,” Jirsa said. The simulations still have to overcome the same challenge.

Understanding where in the patients’ brains seizures arise can give scientists a better idea of how to treat them and whether to use surgery versus medications.

The Human Brain Project

A network not unlike the brain’s own

Though the HBP will be closing this year, its legacy continues in various studies, spin-off companies, and its online platform, EBRAINS. “The HBP is one of the earliest brain initiatives in the world, and the 10-year long-term goal has united many researchers to collaborate on brain sciences with advanced computational tools,” Wang said. “Beyond the many research articles and projects collaborated on during the HBP, the online neuroscience research infrastructure EBRAINS will be left as a legacy even after the project ends.”

Those who worked within the HBP see the end of this project as the next step in neuroscience research. “Neuroscience has come closer to very meaningful applications through the systematic link with new digital technologies and collaborative work,” Jirsa stated. “In that way, the project really had a pioneering role.” It also created a level of interconnectedness within the neuroscience research community that never existed before—a network not unlike the brain’s own. “Interconnectedness is an important advance and prerequisite for progress,” Jirsa said. “The neuroscience community has in the past been rather fragmented and this has dramatically changed in recent years thanks to the Human Brain Project.”

According to its website, by 2023 HBP’s network counted over 500 scientists from over 123 institutions and 16 different countries, creating one of the largest multi-national research groups in the world. Even though the project hasn’t produced the in-silico brain as Markram envisioned it, the HBP created a communal mind with immense potential. “It has challenged us to think beyond the boundaries of our own laboratories,” Jirsa said, “and enabled us to go much further together than we could have ever conceived going by ourselves.”

Regenerative medicine has come a long way, baby

After a cloned baby sheep, what started as one of the most controversial areas in medicine is now promising to transform it.

The field of regenerative medicine had a shaky start. In 2002, when news spread about the first cloned animal, Dolly the sheep, a raucous debate ensued. Scary headlines and organized opposition groups put pressure on government leaders, who responded by tightening restrictions on this type of research.

Fast forward to today, and regenerative medicine, which focuses on making unhealthy tissues and organs healthy again, is rewriting the code to healing many disorders, though it’s still young enough to be considered nascent. What started as one of the most controversial areas in medicine is now promising to transform it.

Progress in the lab has addressed previous concerns. Back in the early 2000s, some of the most fervent controversy centered around somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), the process used by scientists to produce Dolly. There was fear that this technique could be used in humans, with possibly adverse effects, considering the many medical problems of the animals who had been cloned.

But today, scientists have discovered better approaches with fewer risks. Pioneers in the field are embracing new possibilities for cellular reprogramming, 3D organ printing, AI collaboration, and even growing organs in space. It could bring a new era of personalized medicine for longer, healthier lives - while potentially sparking new controversies.

Engineering tissues from amniotic fluids

Work in regenerative medicine seeks to reverse damage to organs and tissues by culling, modifying and replacing cells in the human body. Scientists in this field reach deep into the mechanisms of diseases and the breakdowns of cells, the little workhorses that perform all life-giving processes. If cells can’t do their jobs, they take whole organs and systems down with them. Regenerative medicine seeks to harness the power of healthy cells derived from stem cells to do the work that can literally restore patients to a state of health—by giving them healthy, functioning tissues and organs.

Modern-day regenerative medicine takes its origin from the 1998 isolation of human embryonic stem cells, first achieved by John Gearhart at Johns Hopkins University. Gearhart isolated the pluripotent cells that can differentiate into virtually every kind of cell in the human body. There was a raging controversy about the use of these cells in research because at that time they came exclusively from early-stage embryos or fetal tissue.

Back then, the highly controversial SCNT cells were the only way to produce genetically matched stem cells to treat patients. Since then, the picture has changed radically because other sources of highly versatile stem cells have been developed. Today, scientists can derive stem cells from amniotic fluid or reprogram patients’ skin cells back to an immature state, so they can differentiate into whatever types of cells the patient needs.

In the context of medical history, the field of regenerative medicine is progressing at a dizzying speed. But for those living with aggressive or chronic illnesses, it can seem that the wheels of medical progress grind slowly.

The ethical debate has been dialed back and, in the last few decades, the field has produced important innovations, spurring the development of whole new FDA processes and categories, says Anthony Atala, a bioengineer and director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Atala and a large team of researchers have pioneered many of the first applications of 3D printed tissues and organs using cells developed from patients or those obtained from amniotic fluid or placentas.

His lab, considered to be the largest devoted to translational regenerative medicine, is currently working with 40 different engineered human tissues. Sixteen of them have been transplanted into patients. That includes skin, bladders, urethras, muscles, kidneys and vaginal organs, to name just a few.

These achievements are made possible by converging disciplines and technologies, such as cell therapies, bioengineering, gene editing, nanotechnology and 3D printing, to create living tissues and organs for human transplants. Atala is currently overseeing clinical trials to test the safety of tissues and organs engineered in the Wake Forest lab, a significant step toward FDA approval.

In the context of medical history, the field of regenerative medicine is progressing at a dizzying speed. But for those living with aggressive or chronic illnesses, it can seem that the wheels of medical progress grind slowly.

“It’s never fast enough,” Atala says. “We want to get new treatments into the clinic faster, but the reality is that you have to dot all your i’s and cross all your t’s—and rightly so, for the sake of patient safety. People want predictions, but you can never predict how much work it will take to go from conceptualization to utilization.”

As a surgeon, he also treats patients and is able to follow transplant recipients. “At the end of the day, the goal is to get these technologies into patients, and working with the patients is a very rewarding experience,” he says. Will the 3D printed organs ever outrun the shortage of donated organs? “That’s the hope,” Atala says, “but this technology won’t eliminate the need for them in our lifetime.”

New methods are out of this world

Jeanne Loring, another pioneer in the field and director of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Scripps Research Institute in San Diego, says that investment in regenerative medicine is not only paying off, but is leading to truly personalized medicine, one of the holy grails of modern science.

This is because a patient’s own skin cells can be reprogrammed to become replacements for various malfunctioning cells causing incurable diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, macular degeneration and Parkinson’s. If the cells are obtained from a source other than the patient, they can be rejected by the immune system. This means that patients need lifelong immunosuppression, which isn’t ideal. “With Covid,” says Loring, “I became acutely aware of the dangers of immunosuppression.” Using the patient’s own cells eliminates that problem.

Microgravity conditions make it easier for the cells to form three-dimensional structures, which could more easily lead to the growing of whole organs. In fact, Loring's own cells have been sent to the ISS for study.

Loring has a special interest in neurons, or brain cells that can be developed by manipulating cells found in the skin. She is looking to eventually treat Parkinson’s disease using them. The manipulated cells produce dopamine, the critical hormone or neurotransmitter lacking in the brains of patients. A company she founded plans to start a Phase I clinical trial using cell therapies for Parkinson’s soon, she says.

This is the culmination of many years of basic research on her part, some of it on her own cells. In 2007, Loring had her own cells reprogrammed, so there’s a cell line that carries her DNA. “They’re just like embryonic stem cells, but personal,” she said.

Loring has another special interest—sending immature cells into space to be studied at the International Space Station. There, microgravity conditions make it easier for the cells to form three-dimensional structures, which could more easily lead to the growing of whole organs. In fact, her own cells have been sent to the ISS for study. “My colleagues and I have completed four missions at the space station,” she says. “The last cells came down last August. They were my own cells reprogrammed into pluripotent cells in 2009. No one else can say that,” she adds.

Future controversies and tipping points

Although the original SCNT debate has calmed down, more controversies may arise, Loring thinks.

One of them could concern growing synthetic embryos. The embryos are ultimately derived from embryonic stem cells, and it’s not clear to what stage these embryos can or will be grown in an artificial uterus—another recent invention. The science, so far done only in animals, is still new and has not been widely publicized but, eventually, “People will notice the production of synthetic embryos and growing them in an artificial uterus,” Loring says. It’s likely to incite many of the same reactions as the use of embryonic stem cells.

Bernard Siegel, the founder and director of the Regenerative Medicine Foundation and executive director of the newly formed Healthspan Action Coalition (HSAC), believes that stem cell science is rapidly approaching tipping point and changing all of medical science. (For disclosure, I do consulting work for HSAC). Siegel says that regenerative medicine has become a new pillar of medicine that has recently been fast-tracked by new technology.

Artificial intelligence is speeding up discoveries and the convergence of key disciplines, as demonstrated in Atala’s lab, which is creating complex new medical products that replace the body’s natural parts. Just as importantly, those parts are genetically matched and pose no risk of rejection.

These new technologies must be regulated, which can be a challenge, Siegel notes. “Cell therapies represent a challenge to the existing regulatory structure, including payment, reimbursement and infrastructure issues that 20 years ago, didn’t exist.” Now the FDA and other agencies are faced with this revolution, and they’re just beginning to adapt.

Siegel cited the 2021 FDA Modernization Act as a major step. The Act allows drug developers to use alternatives to animal testing in investigating the safety and efficacy of new compounds, loosening the agency’s requirement for extensive animal testing before a new drug can move into clinical trials. The Act is a recognition of the profound effect that cultured human cells are having on research. Being able to test drugs using actual human cells promises to be far safer and more accurate in predicting how they will act in the human body, and could accelerate drug development.

Siegel, a longtime veteran and founding father of several health advocacy organizations, believes this work helped bring cell therapies to people sooner rather than later. His new focus, through the HSAC, is to leverage regenerative medicine into extending not just the lifespan but the worldwide human healthspan, the period of life lived with health and vigor. “When you look at the HSAC as a tree,” asks Siegel, “what are the roots of that tree? Stem cell science and the huge ecosystem it has created.” The study of human aging is another root to the tree that has potential to lengthen healthspans.

The revolutionary science underlying the extension of the healthspan needs to be available to the whole world, Siegel says. “We need to take all these roots and come up with a way to improve the life of all mankind,” he says. “Everyone should be able to take advantage of this promising new world.”