The Scientist Behind the Pap Smear Saved Countless Women from Cervical Cancer

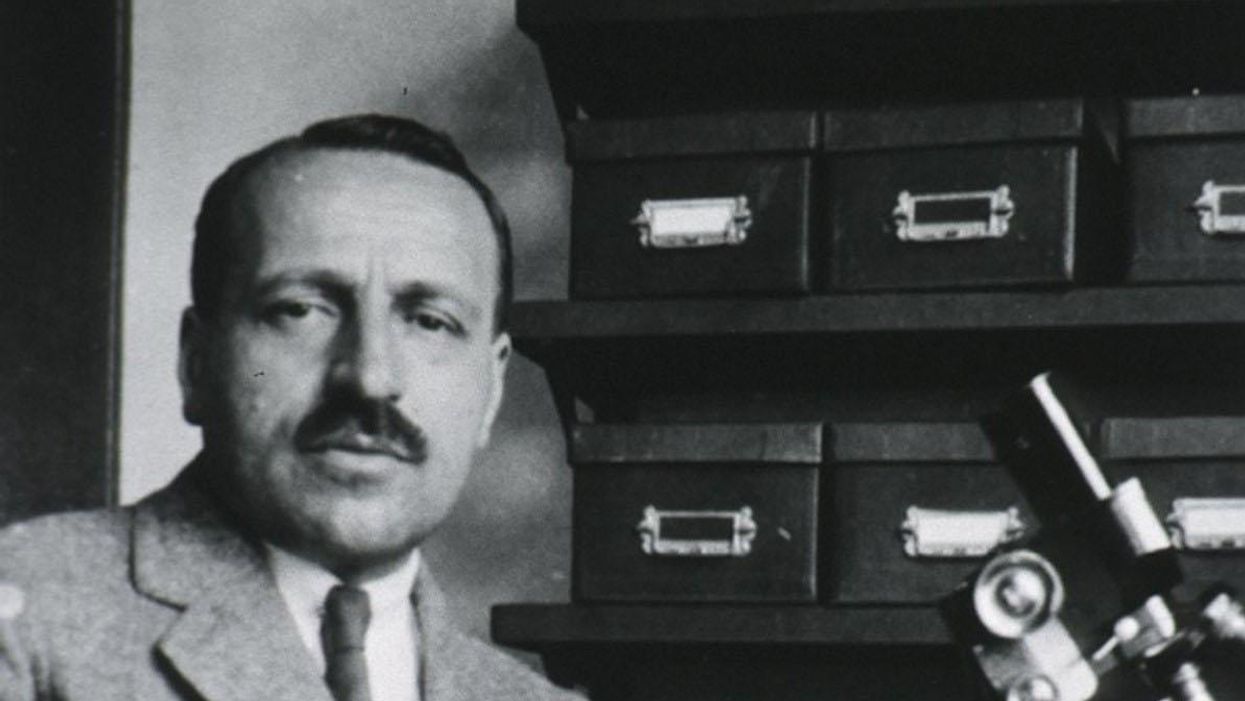

George Papanicolaou (1883-1962), Greek-born American physician developed a simple cytological test for cervical cancer in 1928.

For decades, women around the world have made the annual pilgrimage to their doctor for the dreaded but potentially life-saving Papanicolaou test, a gynecological exam to screen for cervical cancer named for Georgios Papanicolaou, the Greek immigrant who developed it.

The Pap smear, as it is commonly known, is credited for reducing cervical cancer mortality by 70% since the 1960s; the American Cancer Society (ACS) still ranks the Pap as the most successful screening test for preventing serious malignancies. Nonetheless, the agency, as well as other medical panels, including the US Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology are making a strong push to replace the Pap with the more sensitive high-risk HPV screening test for the human papillomavirus virus, which causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

So, how was the Pap developed and how did it become the gold standard of cervical cancer detection for more than 60 years?

Born on May 13, 1883, on the island of Euboea, Greece, Georgios Papanicolaou attended the University of Athens where he majored in music and the humanities before earning his medical degree in 1904 and PhD from the University of Munich six years later. In Europe, Papanicolaou was an assistant military surgeon during the Balkan War, a psychologist for an expedition of the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco and a caregiver for leprosy patients.

When he and his wife, Andromache Mavroyenous (Mary), arrived at Ellis Island on October 19, 1913, the young couple had scarcely more than the $250 minimum required to immigrate, spoke no English and had no job prospects. They worked a series of menial jobs--department store sales clerk, rug salesman, newspaper clerk, restaurant violinist--before Papanicolaou landed a position as an anatomy assistant at Cornell University and Mary was hired as his lab assistant, an arrangement that would last for the next 50 years.

Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

In his early research, Papanikolaou used guinea pigs to prove that gender is determined by the X and Y chromosomes. Using a pediatric nasal speculum, he collected and microscopically examined vaginal secretions of guinea pigs, which revealed distinct cell changes connected to the menstrual cycle. He moved on to study reproductive patterns in humans, beginning with his faithful wife, Mary, who not only endured his almost-daily cervical exams for decades, but also recruited friends as early research participants.

Writing in the medical journal Growth in 1920, the scientist outlined his theory that a microscopic smear of vaginal fluid could detect the presence of cancer cells in the uterus. Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

At this time, cervical cancer was the number one cancer killer of American women but physicians were skeptical of these new findings. They continued to rely on biopsy and curettage to diagnose and treat the disease until Papanicolaou's discovery was published in American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. An inexpensive, easy-to-perform test that could detect cervical cancer, precancerous dysplasia and other cytological diseases was a sea change. Between 1975 and 2001, the cervical cancer rate was cut in half.

Papanicolaou became Emeritus Professor at Cornell University Medical College and received numerous awards, including the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research and the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society. His image was featured on the Greek currency and the US Post Office issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. But international acclaim didn't lead to a more relaxed schedule. The researcher continued to work seven days a week and refused to take vacations.

After nearly 50 years, Papanicolaou left Cornell to head and develop the Cancer Institute of Miami. He died of a heart attack on February 19, 1962, just three months after his arrival. Mary continued to work in the renamed Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute until her death 20 years later.

The annual pap smear was originally tied to renewing a birth control prescription. Canada began recommending Pap exams every three years in 1978. The United States followed suit in 2012, noting that it takes many years for cervical cancer to develop. In September 2020, the American Cancer Society recommended delaying the first gynecological pelvic exam until age 25 and replacing the Pap test completely with the more accurate human papillomavirus (HPV) test every five years as the technology becomes more widely available.

Not everyone agrees that it's time to do away with this proven screening method, though. The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 28% higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnicities.

Whether the Pap is administered every year, every three years or not at all, Papanicolaou will always be known as the medical hero who saved countless women who would otherwise have succumbed to cervical cancer.

A leading virologist reflects on the past year and the unknowns about COVID-19 that we still need to solve.

On the one-year anniversary of the World Health Organization declaring SARS-CoV-2 a global pandemic, it's hard to believe that so much and yet so little time has passed. The past twelve months seem to have dragged by, with each day feeling like an eternity, yet also it feels as though it has flashed by in a blur.

Nearly everyone I've spoken with, from recent acquaintances to my closest friends and family, have reported feeling the same odd sense of disconnectedness, which I've taken to calling "pandemic relativity." Just this week, Ellen Cushing published a piece in The Atlantic about the effects of "late-stage pandemic" on memory and cognitive function. Perhaps, thanks to twelve months of living this way, we have all found it that much more difficult to distill the key lessons that will allow us to emerge from the relentless, disconnected grind of our current reality, return to some semblance of normalcy, and take the decisive steps needed to ensure the mistakes of this pandemic are not repeated in the next one.

As a virologist who studies SARS-CoV-2 and other emerging viruses, and who sometimes writes and publicly comments on my thoughts, I've been asked frequently about what we've learned as we approach a year of living in suspension. While I always come up with an answer, the truth is similar to my perception of time: we've learned a lot, but at the same time, that's only served to highlight how much we still don't know. We have uncovered and clarified many scientific truths, but also revealed the limits of our scientific knowledge.

The Most Important Lessons Learned

The dangers of false dichotomies.

From the early days, we have been guilty of binary thinking, and this has touched nearly every aspect of the pandemic. The following statements are not true, but the narratives are all too common: The only outcomes of COVID-19 are full recovery or death. Masks either work perfectly or they don't work at all. Transmission only occurs entirely by droplets or is entirely airborne. Children are either complete immune or they are equally as susceptible as adults. Vaccines either completely protect against infection and illness or they are completely useless. Any true student of biology can tell you that there are very rarely binary certainties that apply to every situation, but sensible public health advice can be rapidly derailed by discussing biological realities that exist on a continuum as if they are all categorically true or false.

It's a natural impulse to reduce complex systems to a choice of two options, and also to seek absolute certainty. A challenge for all scientists is how to communicate uncertainty when many people are understandably frustrated at this point and sick of hearing "we don't know." If we don't know now, when will we know? How much do we need to know to make good decisions? When will we get back to "normal"? In trying to simplify complex scientific concepts, we've made them hopelessly complicated. An important lesson going forward is that we should move away from black and white conversations about the emerging science and embrace the shades of gray, with all the nuance and uncertainty that entails.

Novel pandemic viruses can be controlled without a vaccine or effective antiviral therapeutics, and there is no one right way to do so.

Coronaviruses are very different from influenza.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the superficial similarities between SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses have inevitably led to comparisons: both are primarily respiratory viruses with some symptoms in common, both have a relatively low overall mortality rate, both are zoonotic viruses that spilled over into the human population from animals, both are enveloped viruses that use RNA, rather than DNA, as their genetic material.

But these similarities disguise the fact that these are two fundamentally different pathogens. They have very different biology at virtually every step of the viral replication cycle, or the process that a virus goes through when it infects a cell and transforms it into a virus factory. SARS-CoV-2 enters cells by interacting with a protein on cell surfaces called ACE-2, while influenza viruses interact with a sugar molecule called sialic acid that "decorates" cell surface proteins. This means the viruses infect different types of cells in the respiratory tract and throughout the body. They also encode vastly different types of viral proteins meant to subvert and hijack the cells they infect: the genome of influenza virus is less than half the size of the genome of SARS-CoV-2, and encodes fewer than half as many viral proteins that can interact with the host cell.

As a result, these viruses each interact with host cells in unique ways and induce different responses to infection. The host response to infection is critically important for determining disease severity in both influenza and COVID-19, with the most severe disease associated with an uncontrolled inflammatory response that results in damaging the lungs and other affected tissues. Indeed, comparative studies have now shown that COVID-19 and influenza infection induce very different host response profiles in infected cells, leading to fundamentally different diseases. Our early reliance on pandemic response plans and public health strategies designed for influenza virus was a mistake, and this will be critical to preparedness and improved response plans going forward.

Transmission is situational.

Another way in which SARS-CoV-2 is very different from influenza is how it spreads through a population, which is relevant to how it is transmitted. Early on, many people focused on the fact that the basic reproduction number (R0) of SARS-CoV-2 was between 2 and 4, similar to the 1918 influenza pandemic. R0 describes the number of people that an infected person will transmit the virus to, but this is an average.

Another key measurement epidemiologists use to look at spread is dispersion, or patterns of transmission. If R0 is 2, and you have a population of 10 people, does that mean that all 10 people transmitted the virus to exactly 2 people? Or did 4 of the people each transmit to 5 people, with the other 6 of the 10 transmitting to nobody? In both situations, the average number of new infections is still 2, but the latter situation is described as overdispersion. While influenza is typically not very overdispersed, SARS-CoV-2 is heavily overdispersed. This is reflected in the high frequency of "superspreading events", where many people are infected at the same time.

Superspreading events are highly dependent on circumstances that need to align to create a conducive environment for transmission. SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted by either inhalation of infectious aerosols (smaller respiratory particles suspended in the air) or direct contact with infectious droplets (larger respiratory particles that can be transferred from the body to the nose or mouth). This means that transmission is more likely to occur in situations with increased exposure risk. The risk is additive, with the likelihood of transmission being higher with more potential sources of virus (people from different households), higher respiratory particle emissions (lack of masks and/or shouting or singing), a physical environment that concentrates potentially infectious particles (an enclosed, poorly ventilated indoor space), close physical proximity (crowding), and increased exposure time.

We have seen repeatedly that when these conditions are met, such as in crowded bars or restaurants, gyms, cruise ships, buses, or weddings, superspreading can occur. The good news, however, is that identifying all these different risk factors has also allowed us to identify methods to mitigate transmission, and these are also additive: masks, physical distancing, avoiding enclosed spaces, limiting interactions with people outside your household, improving ventilation, and practicing good hand hygiene all reduce exposure risk.

Presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission are critical to controlling a pandemic.

Another critical early mistake was assuming that SARS-CoV-2 would be transmitted only by symptomatic people. This was an understandable assumption to make, as people infected with "classic" SARS-CoV reliably developed fevers and could be identified based on body temperature and symptom screening. However, by March 2020, it was apparent that symptom-based screening was inadequate. The symptoms of COVID-19 fall along a very broad spectrum, ranging from completely asymptomatic infection to lethal pneumonia, with everything from loss of taste and smell to "COVID toes" to diarrhea to kidney failure to strokes in between.

Furthermore, last spring several studies showed that viral loads in the nose and throat were highest at the time of symptom onset, suggesting that people were likely to be contagious before they would be aware that they were sick. This created a tremendous challenge that repeatedly thwarted efforts to control community transmission in many countries, including the U.S. Without sufficient testing and surveillance, and with prevalence too high to enable robust contact tracing, efforts to identify and quarantine exposed people were unsuccessful. While the percentage of cases resulting from silent asymptomatic or presymptomatic transmission is still not precisely determined, it may account for nearly half of new infections and has been observed repeatedly. However, our policies have not caught up, and overeager reopening and blanket lifting of mask mandates often fail to account for contagious people who don't realize they are infected. Unfortunately, it's now also well-established that prematurely letting up on precautions can drive new surges in case numbers.

There's more than one way to stop a pandemic. While we've certainly seen examples of failed pandemic responses by looking at the U.S. and most of Western Europe, there have been a number of other countries that have very effectively controlled the pandemic within their borders. This hasn't been a one-size-fits-all approach, either. China infamously instituted a draconian lockdown in late January after the pandemic quickly spread from Wuhan to the rest of the country. A number of other countries, including Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Vietnam, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, have implemented various combinations of policy measures (travel restrictions, lockdowns), epidemiological approaches (contact tracing, isolation and quarantine), data collection (testing capacity and surveillance), and mitigation measures (mask availability and mandates, exposure risk reduction education campaigns), that have effectively kept prevalence low and in some cases eliminated COVID-19 altogether. It shows that novel pandemic viruses can be controlled without a vaccine or effective antiviral therapeutics, and also that there is no one right way to do so.

We can develop safe, effective vaccines in record time.

Last March, Dr. Anthony S. Fauci estimated that a vaccine might be available in 12 to 18 months. At the time this was thought to be an extremely optimistic estimate, given that vaccines typically take years to design, develop, and test to ensure they are safe and effective. So how did we go from the drawing board to authorized vaccines, which so far appear to be very safe and effective, in less than a year? In part this is due to streamlining the clinical trial process, allowing previously sequential steps in the pipeline to occur simultaneously, such as phase 3 clinical trials and manufacturing.

The expedited trial process also built upon previous studies with the vaccine technologies, including extensive preclinical studies and clinical trials that tested mRNA (Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna) and adenovirus-vectored (Johnson and Johnson and AstraZeneca) vaccines against other viruses, including MERS-CoV, a cousin of SARS-CoV-2. Prior to the phase 3 clinical trials "reading out" (amassing enough data to enable a statistically robust appraisal of their safety and efficacy), our expectations were modest, hoping for 50 to 60% protection against COVID-19. Thus far, all the vaccines that have completed phase 3 trials have exceeded that expectation. While future vaccines will likely still take years to fully evaluate, we can apply the achievements of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to make the regulatory process more efficient for other vaccines, as well as develop ways to further expedite the process in emergencies without compromising safety or effectiveness. A more efficient regulatory environment could improve access to other technologies, such as promising new tests and therapeutics, as well.

The Biggest Unknowns

While we have made extraordinary strides forward in better understanding SARS-CoV-2 and both the triumphs and the failures of the response to the greatest public health challenge of our lifetime, the lessons we've learned have highlighted the many questions that remain. We will be studying many aspects of the pandemic for decades. Long after SARS-CoV-2 is finished with humanity on a global scale, we will not be finished with it. Some of these remaining questions won't have easy answers, and in fact may not even be answerable. But it is critical to engage with these questions as we move into a post-pandemic future.

The origin of SARS-CoV-2.

This topic is as confusing and murky as it is contentious, proving to be as confounding to science as it is disruptive to geopolitics. Multiple hypotheses abound: SARS-CoV-2 emerged into the human population naturally, passing from an infected animal to an unlucky human in the wrong place at the wrong time in a process called zoonotic spillover. This natural origin hypothesis is considered the most likely, as this is overwhelmingly the most common path for novel viruses to emerge in the human population.

Tracing SARS-CoV-2 back to its source is critical for both understanding how this pandemic began and preventing the emergence of SARS-CoV-3, which almost certainly is circulating in wildlife along with a frighteningly large number of other potential pandemic pathogens.

However, the evidence supporting this hypothesis is scant, and limited to genetic analyses that don't indicate anything artificial or engineered about the SARS-CoV-2 genome, as well as some very small studies suggesting that people who live close to bat caves in southern China have antibodies to closely related viruses. Such uncertainty has led to several other hypotheses, including that the virus emerged from a laboratory at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, either through accident or design. While there is far more speculation than evidence affirming any laboratory origin hypothesis, neither can be definitively excluded and both should be fairly investigated. In addition, the Chinese government has suggested that SARS-CoV-2 was imported via frozen seafood from Europe or North America. This hypothesis strains credulity, given that the most closely related viruses have been identified in China and transmission by indirect contact (with contaminated objects, or fomites, is thought to be uncommon), but it still should be ruled out objectively.

About the only thing most experts agree on is that SARS-CoV-2 evolved from an ancestral betacoronavirus that likely was circulating in bats. However, because we have not yet found that ancestral virus in nature, we are left still looking. Sometimes origin investigations into zoonotic origins can take decades, since we live in a big world, with many wild animals carrying many different viruses at different times in their lives. Trying to find the immediate forbear of SARS-CoV-2 in wildlife is like seeking a very specific tiny needle in a planet-sized haystack that is also littered with other tiny needles.

To further complicate matters, there is the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 did not spill over from bats to humans directly, but stopped off in another species along the way. Intermediary species have been involved in the transmission of both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, and we already know that SARS-CoV-2 can infect other animal species, including minks, dogs, and cats.

And if the science weren't complex enough, conducting any type of origin investigation, but particularly a rigorous independent investigation of lab origin theories, depends on other countries maintaining a productive diplomatic relationship with the Chinese government. That relationship erodes every time another piece is published outside China that treats laboratory origin as a foregone conclusion. Tracing SARS-CoV-2 back to its source is critical for both understanding how this pandemic began and preventing the emergence of SARS-CoV-3, which almost certainly is circulating in wildlife along with a frighteningly large number of other potential pandemic pathogens. But it won't be easy and we need to prepare ourselves for the possibility of a very long and arduous search for answers.

The long-term consequences of COVID-19.

While it is not clear how common "long COVID" is, one thing is certain: it has impacted a substantial number of COVID-19 survivors' lives. It remains unknown what predisposes a person to this outcome, now dubbed post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Nor does anyone truly know how long it lasts, or even what the most common presentation of it looks like. Many patients have reported a diverse array of symptoms, some very severe, that have persisted for months.

PASC can range from recurring neurological problems to hair and tooth loss to permanent lung injury. Some people have reported relapsing pain and severe fatigue similar to myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome. Even more troubling, PASC can be severe in patients who reported having extremely mild acute COVID-19. Last month, the National Institutes of Health announced plans to study PASC in detail, but it may be some time before we know the cause (or causes) of PASC, much less how to treat it and ameliorate its impact on those suffering from it. But the potential for long-term debilitating illness persisting long after the resolution of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection suggests that even when the pandemic is behind us, public health will continue to struggle with the legacy of COVID-19.

Immune correlates of protection and durability.

While vaccine trials were designed to sacrifice little in the way of assessing short-term efficacy, they did not assess the length of time that protective immunity will last. This was because of the urgency of the situation, and allowed us to begin vaccinating as soon as we learned that the vaccines were safe and effective in the short term. Durability studies are one reason why normally vaccine trials can take over a decade, as unfortunately the only way to assess how long a vaccine lasts is to wait and see when protection begins to wane.

Furthermore, because the virus is novel and the technologies underlying the vaccine platforms are being used for the first time at population scale, we haven't yet defined correlates of protection for the vaccines. Correlates of protection are easily measurable features, such as antibody levels or cell counts, that can be used as surrogates for vaccine function. In other words, what we are missing is the knowledge of how many antibodies, or T-cells, does your immune system actually need to protect you from infection? We know that a high number is protective, but the question is how high.

Until we have enough data to define these correlates, we have to continue to follow trial participants and analyze observational studies of vaccinated individuals, which can be tedious as well as time-consuming. So it may be some time before we can advise people confidently about how long vaccine protection will last beyond a year or so, based on the duration of immune function in people who have recovered from natural SARS-CoV-2 infection. The good news is that protective immune responses can be easily restored with a booster shot, but that will present major logistical challenges if needed while global immunization efforts are still underway.

What price will we pay for nationalizing vaccine responses?

Finally, one of the biggest questions as we move into the post-pandemic future in the developed world is what the decision to respond nationally, rather than as a cooperative global community, will cost us in terms of truly ending the pandemic. Without question, in countries like the U.S., which will have enough vaccine doses in the next few months to vaccinate every American who wants one, the pandemic will end for most people's daily lives. But globally, the reality is very different. Many countries have yet to administer a single dose of any vaccine. While this may not seem relevant to people who do not intend to travel to those countries, it is relevant to every human being on earth. None of us are safe until all of us are safe.

Viruses infect their hosts regardless of what passport they carry. Pandemics, by definition, are global epidemics, and thus impact the global population. If people are vaccinated only in certain countries, SARS-CoV-2 can continue to circulate in populations with less immunization and fewer barriers to infection. As the U.S. today reaches this grim anniversary along with the rest of the world, we would do well to remember the lessons we've learned as we forge ahead with filling the remaining gaps in our knowledge.

No, the New COVID Vaccine Is Not "Morally Compromised"

As the proportion of vaccinated elderly people increases, family reunions become possible again -- but not if people reject the vaccines on religious grounds.

The approval of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine has been heralded as a major advance. A single-dose vaccine that is highly efficacious at removing the ability of the virus to cause severe disease, hospitalization, and death (even in the face of variants) is nothing less than pathbreaking. Anyone who is offered this vaccine should take it. However, one group advises its adherents to preferentially request the Moderna or Pfizer vaccines instead in the quest for morally "irreproachable" vaccines.

Is this group concerned about lower numerical efficacy in clinical trials? No, it seems that they have deemed the J&J vaccine "morally compromised". The group is the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and if something is "morally compromised" it is surely not the vaccine. (Notably Pope Francis has not taken such a stance).

At issue is a cell line used to manufacture the vaccine. Specifically, a cell line used to grow the adenovirus vector used in the vaccine. The purpose of the vector is to carry a genetic snippet of the coronavirus spike protein into the body, like a Trojan Horse ferrying in an enemy combatant, in order to safely trigger an immune response without any chance of causing COVID-19 itself.

It is my hope that the country's 50 million Catholics do not heed the U.S. Conference of Bishops' potentially deadly advice and instead obtain whichever vaccine is available to them as soon as possible.

The cell line of the vector, known as PER.C6, was derived from a fetus that was aborted in 1985. This cell line is prolific in biotechnology, as are other fetal-derived cell lines such as HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney), used in the manufacture of the Astra Zeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Indeed, fetal cell lines are used in the manufacture of critical vaccines directed against pathogens such as hepatitis A, rubella, rabies, chickenpox, and shingles and were used to test the Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines (which, accordingly, the U.S. Conference of Bishops deem to only raise moral "concerns").

As such, fetal cell lines from abortions are a common and critical component of biotechnology that we all rely on to improve our health. Such cell lines have been used to help find treatments for cancer, Ebola, and many other diseases.

Dr. Andrea Gambotto, a vaccine scientist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, explained to Science magazine last year why fetal cells are so important to vaccine development: "Cultured [nonhuman] animal cells can produce the same proteins, but they would be decorated with different sugar molecules, which—in the case of vaccines—runs the risk of failing to evoke a robust and specific immune response." Thus, the fetal cells' human origins are key to their effectiveness.

So why the opposition to this life-saving technology, especially in the midst of the deadliest pandemic in over a century? How could such a technology be "morally compromised" when morality, as I understand it, is a code of values to guide human life on Earth with the purpose of enhancing well-being?

By any measure, the J&J vaccine accomplishes that, since human life, not embryonic or fetal life, is the standard of value. An embryo or fetus in the earlier stages of development, while harboring the potential to grow into a human being, is not the moral equivalent of a person. Thus, creating life-saving medical technology using cells that would have otherwise been destroyed is not in conflict with a proper moral code. To me, it is nihilistic to oppose these vaccines on the grounds cited by the U.S. Conference of Bishops.

Reason, the rational faculty, is the human means of knowledge. It is what one should wield when approaching a scientific or health issue. Appeals from clerics, devoid of any need to tether their principles to this world, should not have any bearing on one's medical decision-making.

In the Dark Ages, the Catholic Church opposed all forms of scientific inquiry, even castigating science and curiosity as the "lust of the eyes": One early Middle Ages church father reveled in his rejection of reality and evidence, proudly declaring, "I believe because it is absurd." This organization, which tyrannized scientists such as Galileo and murdered the Italian cosmologist Bruno, today has shown itself to still harbor anti-science sentiments in its ranks.

It is my hope that the country's 50 million Catholics do not heed the U.S. Conference of Bishops' potentially deadly advice and instead obtain whichever vaccine is available to them as soon as possible. When judged using the correct standard of value, vaccines using fetal cell lines in their development are an unequivocal good -- while those who attempt to undermine them deserve a different category altogether.

Dr. Adalja is focused on emerging infectious disease, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity. He has served on US government panels tasked with developing guidelines for the treatment of plague, botulism, and anthrax in mass casualty settings and the system of care for infectious disease emergencies, and as an external advisor to the New York City Health and Hospital Emergency Management Highly Infectious Disease training program, as well as on a FEMA working group on nuclear disaster recovery. Dr. Adalja is an Associate Editor of the journal Health Security. He was a coeditor of the volume Global Catastrophic Biological Risks, a contributing author for the Handbook of Bioterrorism and Disaster Medicine, the Emergency Medicine CorePendium, Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple, UpToDate's section on biological terrorism, and a NATO volume on bioterrorism. He has also published in such journals as the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Emerging Infectious Diseases, and the Annals of Emergency Medicine. He is a board-certified physician in internal medicine, emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and critical care medicine. Follow him on Twitter: @AmeshAA