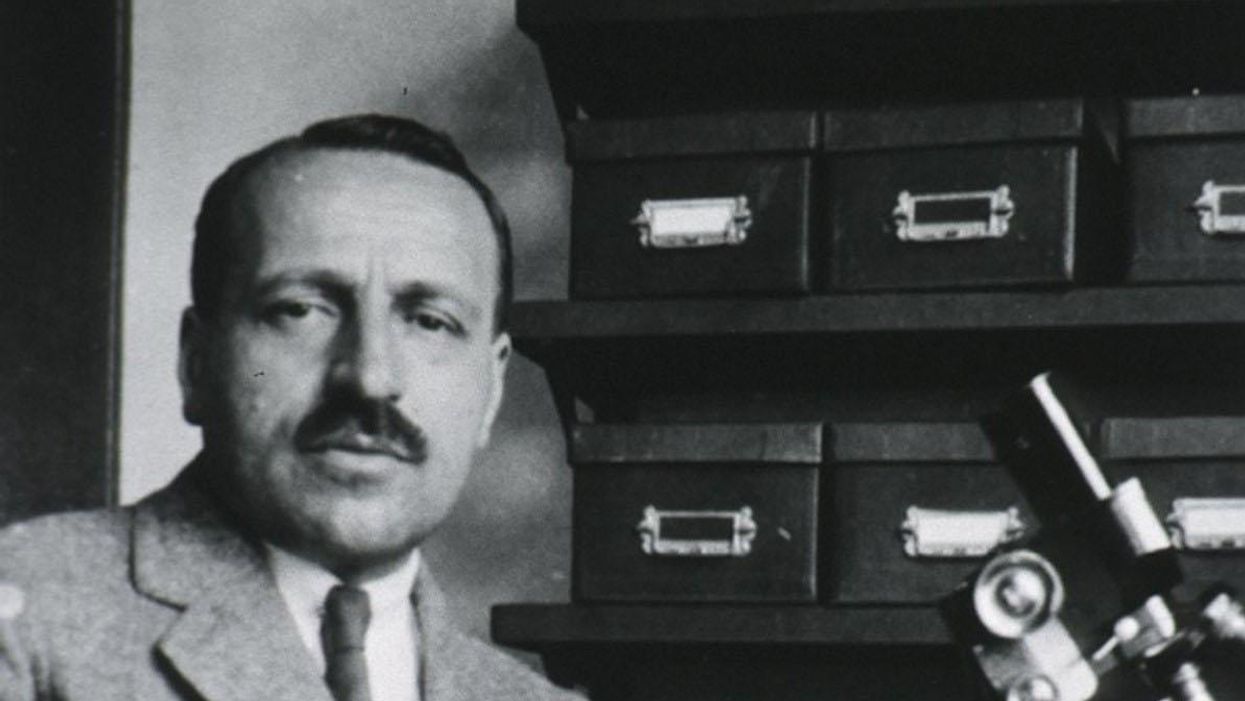

The Scientist Behind the Pap Smear Saved Countless Women from Cervical Cancer

George Papanicolaou (1883-1962), Greek-born American physician developed a simple cytological test for cervical cancer in 1928.

For decades, women around the world have made the annual pilgrimage to their doctor for the dreaded but potentially life-saving Papanicolaou test, a gynecological exam to screen for cervical cancer named for Georgios Papanicolaou, the Greek immigrant who developed it.

The Pap smear, as it is commonly known, is credited for reducing cervical cancer mortality by 70% since the 1960s; the American Cancer Society (ACS) still ranks the Pap as the most successful screening test for preventing serious malignancies. Nonetheless, the agency, as well as other medical panels, including the US Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology are making a strong push to replace the Pap with the more sensitive high-risk HPV screening test for the human papillomavirus virus, which causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

So, how was the Pap developed and how did it become the gold standard of cervical cancer detection for more than 60 years?

Born on May 13, 1883, on the island of Euboea, Greece, Georgios Papanicolaou attended the University of Athens where he majored in music and the humanities before earning his medical degree in 1904 and PhD from the University of Munich six years later. In Europe, Papanicolaou was an assistant military surgeon during the Balkan War, a psychologist for an expedition of the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco and a caregiver for leprosy patients.

When he and his wife, Andromache Mavroyenous (Mary), arrived at Ellis Island on October 19, 1913, the young couple had scarcely more than the $250 minimum required to immigrate, spoke no English and had no job prospects. They worked a series of menial jobs--department store sales clerk, rug salesman, newspaper clerk, restaurant violinist--before Papanicolaou landed a position as an anatomy assistant at Cornell University and Mary was hired as his lab assistant, an arrangement that would last for the next 50 years.

Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

In his early research, Papanikolaou used guinea pigs to prove that gender is determined by the X and Y chromosomes. Using a pediatric nasal speculum, he collected and microscopically examined vaginal secretions of guinea pigs, which revealed distinct cell changes connected to the menstrual cycle. He moved on to study reproductive patterns in humans, beginning with his faithful wife, Mary, who not only endured his almost-daily cervical exams for decades, but also recruited friends as early research participants.

Writing in the medical journal Growth in 1920, the scientist outlined his theory that a microscopic smear of vaginal fluid could detect the presence of cancer cells in the uterus. Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

At this time, cervical cancer was the number one cancer killer of American women but physicians were skeptical of these new findings. They continued to rely on biopsy and curettage to diagnose and treat the disease until Papanicolaou's discovery was published in American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. An inexpensive, easy-to-perform test that could detect cervical cancer, precancerous dysplasia and other cytological diseases was a sea change. Between 1975 and 2001, the cervical cancer rate was cut in half.

Papanicolaou became Emeritus Professor at Cornell University Medical College and received numerous awards, including the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research and the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society. His image was featured on the Greek currency and the US Post Office issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. But international acclaim didn't lead to a more relaxed schedule. The researcher continued to work seven days a week and refused to take vacations.

After nearly 50 years, Papanicolaou left Cornell to head and develop the Cancer Institute of Miami. He died of a heart attack on February 19, 1962, just three months after his arrival. Mary continued to work in the renamed Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute until her death 20 years later.

The annual pap smear was originally tied to renewing a birth control prescription. Canada began recommending Pap exams every three years in 1978. The United States followed suit in 2012, noting that it takes many years for cervical cancer to develop. In September 2020, the American Cancer Society recommended delaying the first gynecological pelvic exam until age 25 and replacing the Pap test completely with the more accurate human papillomavirus (HPV) test every five years as the technology becomes more widely available.

Not everyone agrees that it's time to do away with this proven screening method, though. The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 28% higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnicities.

Whether the Pap is administered every year, every three years or not at all, Papanicolaou will always be known as the medical hero who saved countless women who would otherwise have succumbed to cervical cancer.

At the “Apple Store of Doctor’s Offices,” Preventive Care Is High Tech. Is it Worth $150 a Month?

A patient getting examined at health startup Forward.

What if going to the doctor's office could be … nice?

If you didn't have to wait for your appointment, but were ushered right in; if your medical data was all collated and easily searchable on an iPhone app; if a remote scribe took notes while you spoke with your doctor so you could make eye contact with them; if your doctor didn't seem horribly rushed.

Would you go to the doctor to get help staying healthy, rather than just to stop being sick?

Would that change the way you thought about your health? Would you go to the doctor to get help staying healthy, rather than just to stop being sick? And would that, in the long run, be much better for you?

Those are the animating questions for Forward, a healthcare startup devoted to preventive care. Led by founder Adrian Aoun, formerly of Google/Sidewalk labs, Forward opened its first office in San Francisco in 2016 and has since expanded to Los Angeles, Orange County, New York, and Washington, D.C., with a San Diego location opening soon.

It's been described as the "Apple Store of doctor's offices," which in some ways is a reaction to Forward's vibe: Patients have described the offices as having blonde wood, minimalist design, sparkling water on tap — and lots of high-tech gadgets, like the full-body scanner that replaces the standard scale and stethoscope.

The interior of a Forward office.

(Courtesy Forward)

The more crucial difference, though, is its model of care. Forward doesn't take insurance. Instead, patients, or "members," pay a flat $149 per month, along the lines of a subscription service like Netflix or a gym membership. That fee covers visits, messaging with medical staff through the Forward app, the use of a wearable (like a Fitbit or a sleep tracker) if the physician recommends it, plus any bloodwork or diagnostic tests run in the on-site labs. (The company declined to disclose how many people have signed up for memberships.)

Predictability is Forward's other significant, distinguishing feature: No surprise co-pays, or extra charges showing up on a billing statement months later. Everything is wrapped up in the $149 membership fee, unless the physician recommends visiting an outside specialist.

That caveat isn't a small one. It's important to note that Forward is in no way meant to replace standard health insurance. The service is strictly focused on preventive care, so it wouldn't be much use in case of an emergency; it's meant to help people, as far as is possible, avoid that emergency at all.

Ani Okkasian's family recently went through such an emergency. Her 62-year-old father, an active and seemingly healthy man living with diabetes, had been feeling unwell for a while, but struggled to receive constructive follow-up or tests from his doctor. It finally emerged that his liver was severely damaged, and he suffered a stroke — the risk of which can be elevated by liver disease. He seemed to deteriorate completely within mere weeks, Okkasian said, and in January he passed away.

"He was someone who'd go to the doctor regularly and listen to what they said and follow it," Okkasian said. "I shouldn't have had to bury my father at 62. I still believe to my core that his death could have been avoided if the primary care was adequate."

"I could tell that the people who designed [Forward] had lost someone to the legacy system; it was so streamlined and so much clearer."

Okkasian began researching, looking for a better alternative, and discovered Forward. Founder Aoun lost his grandfather to a heart attack; his brother's heart attack at age 31 was the impetus to start Forward.

"I could tell that that was the genesis," Okkasian said. "Having just lost someone, and having had to deal with different aspects of the healthcare industry — how complicated and convoluted that all is — I could tell that the people who designed [Forward] had lost someone to the legacy system; it was so streamlined and so much clearer."

So Who Is Forward For?

The Affordable Care Act mandates that evidence-based preventive care must be covered by insurers without any cost to the patient. Today, 30 million Americans are still living without health insurance; but for most of the population, cost shouldn't prevent access to standard, preventive care, says Benjamin Sommers, a physician and professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health who has studied the effect of the ACA on preventive care access.

For Okkasian and her family, it wasn't a lack of access to primary care that was at issue; it was the quality of that primary care. In 2019, that's probably true for a lot of people.

"How come all other industries have been disturbed except the medical industry?" Okkasian asked. "It's disturbing the most people. We're so advanced in so many ways, but when it comes to the healthcare system, we're not prioritizing the wellness of a person."

Is Forward the answer? Well, probably not for everyone. Its office are only in a handful of cities, and there are limits to how scalable it would be; it's unavoidable that the $149 per month charge restricts access for a lot of people. Those who have insurance through their employer might have a flexible spending account (FSA) that would cover some or all of the membership fee, and Forward has said that 15 percent of their early members came from underserved communities and were offered free plans; but for many others, that's just an unworkable extra cost.

Sommers also sounded a dubious note about a maximalist attitude toward data collection.

"Even though some patients may think that 'more is always better' — more testing, more screening, etc. — this isn't true," he said. "Some types of cancer screening, ovarian cancer screening for instance, are actually harmful or of no benefit, because studies have shown that they don't improve survival or health outcomes, but can lead to unnecessary testing, pain, false positives, anxiety, and other side effects.

"It's really great for people who are in good health, looking to make it better."

"I'm generally skeptical of efforts to charge people more to get 'extra testing' that isn't currently supported by the medical evidence," he added.

But relatively healthy people who want to take a more active approach to their health — or people who have frequent testing needs, like those using the HIV-prevention drug PrEP, and want to avoid co-pays — might benefit from the on-demand, low-friction experience that Forward offers.

"It's really great for people who are in good health, looking to make it better," Okkasian said. "Your experience is simplified to a point where you feel empowered, not scared."

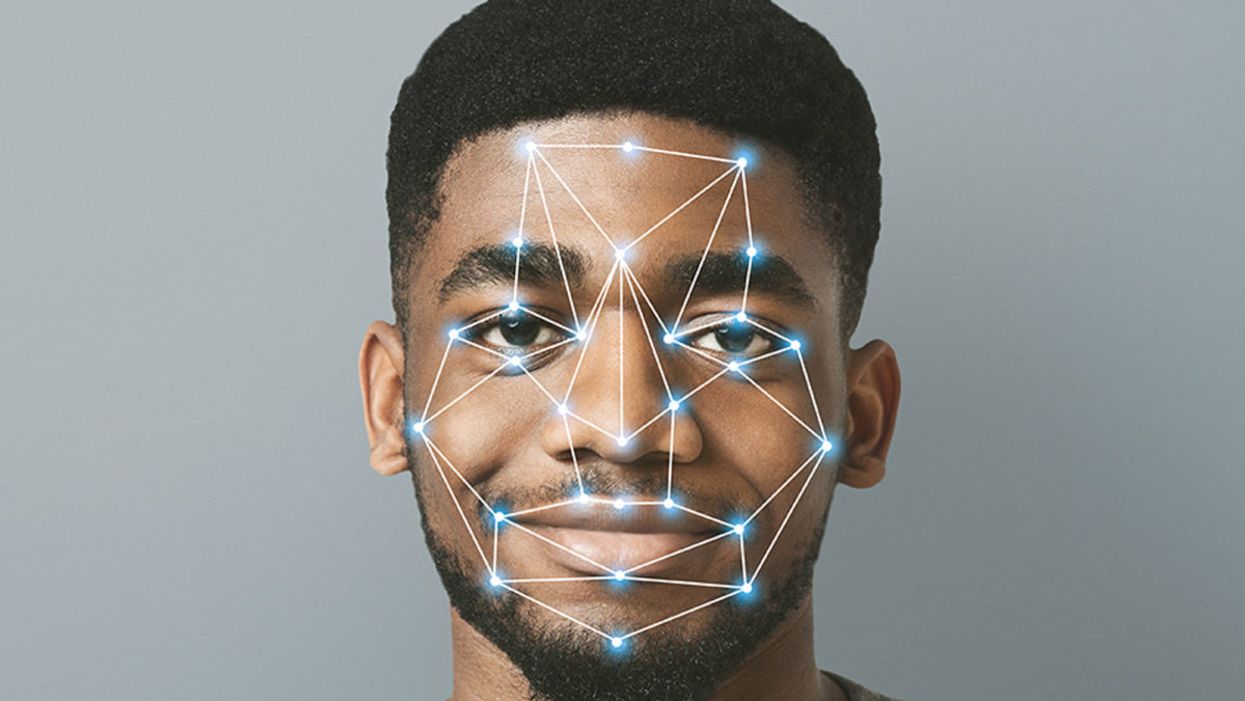

Facial Recognition Can Reduce Racial Profiling and False Arrests

The use of face recognition technology is expanding exponentially right now.

[Editor's Note: This essay is in response to our current Big Question, which we posed to experts with different perspectives: "Do you think the use of facial recognition technology by the police or government should be banned? If so, why? If not, what limits, if any, should be placed on its use?"]

Opposing facial recognition technology has become an article of faith for civil libertarians. Many who supported the bans in cities like San Francisco and Oakland have declared the technology to be inherently racist and abusive.

The greatest danger would be to categorically oppose this technology and pretend that it will simply go away.

I have spent my career as a criminal defense attorney and a civil libertarian -- and I do not fear it. Indeed, I see it as positive so long as it is appropriately regulated and controlled.

We are living in the beginning of a biometric age, where technology uses our physical or biological characteristics for a variety of products and services. It holds great promises as well as great risks. The greatest danger, however, would be to categorically oppose this technology and pretend that it will simply go away.

This is an age driven as much by consumer as it is government demand. Living in denial may be emotionally appealing, but it will only hasten the creation of post-privacy world. If we do not address this emerging technology, movements in public will increasingly result in instant recognition and even tracking. It is the type of fish-bowl society that strips away any expectation of privacy in our interactions and associations.

The biometrics field is expanding exponentially, largely due to the popularity of consumer products using facial recognition technology (FRT) -- from the iPhone program to shopping ones that recognize customers.

But the privacy community is losing this battle because it is using the privacy rationales and doctrines forged in the earlier electronic surveillance periods. Just as generals are often accused of planning to fight the last war, civil libertarians can sometimes cling to past models despite their decreasing relevance in the current world.

I see FRT as having positive implications that are worth pursuing. When properly used, biometrics can actually enhance privacy interests and even reduce racial profiling by reducing false arrests and the warrantless "patdowns" allowed by the Supreme Court. Bans not only deny police a technology widely used by businesses, but return police to the highly flawed default of "eye balling" suspects -- a system with a considerably higher error rate than top FRT programs.

Officers are often wrong and stop a great number of suspects in the hopes of finding a wanted felon.

A study in Australia showed that passport officers who had taken photographs of subjects in ideal conditions nonetheless experienced high error rates when identifying them shortly afterward, including 14 percent false acceptance rates. Currently, officers stop suspects based on their memory from seeing a photograph days or weeks earlier. They are often wrong and stop a great number of suspects in the hopes of finding a wanted felon. The best FRT programs achieve an astonishing accuracy rate, though real-world implementation has challenges that must be addressed.

One legitimate concern raised in early studies showed higher error rates in recognitions for certain groups, particularly African American women. An MIT study finding that error rate prompted major improvements in the algorithms as well as training changes to greatly reduce the frequency of errors. The issue remains a concern, but there is nothing inherently racist in algorithms. These are a set of computer instructions that isolate and process with the parameters and conditions set by creators.

To be sure, there is room for improvement in some algorithms. Tests performed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reportedly showed only an 80 percent accuracy rate in comparing mug shots to pictures of members of Congress when using Amazon's "Rekognition" system. It recently showed the same 80 percent rate in doing the same comparison to members of the California legislators.

However, different algorithms are available with differing levels of performance. Moreover, these products can be set with a lower discrimination level. The fact is that the top algorithms tested by the National Institute of Standards and Technology showed that their accuracy rate is greater than 99 percent.

The greatest threat of biometric technologies is to democratic values.

Assuming a top-performing algorithm is used, the result could be highly beneficial for civil liberties as opposed to the alternative of "eye balling" suspects. Consider the Boston Bombing where police declared a "containment zone" and forced families into the street with their hands in the air.

The suspect, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, moved around Boston and was ultimately found outside the "containment zone" once authorities abandoned near martial law. He was caught on some surveillance systems but not identified. FRT can help law enforcement avoid time-consuming area searches and the questionable practice of forcing people out of their homes to physically examine them.

If we are to avoid a post-privacy world, we will have to redefine what we are trying to protect and reconceive how we hope to protect it. In my view, the greatest threat of biometric technologies is to democratic values. Authoritarian nations like China have made huge investments into FRT precisely because they know that the threat of recognition in public deters citizens from associating or interacting with protesters or dissidents. Recognition changes conduct. That chilling effect is what we have the worry about the most.

Conventional privacy doctrines do not offer much protection. The very concept of "public privacy" is treated as something of an oxymoron by courts. Public acts and associations are treated as lacking any reasonable expectation of privacy. In the same vein, the right to anonymity is not a strong avenue for protection. We are not living in an anonymous world anymore.

Consumers want products like FaceFind, which link their images with others across social media. They like "frictionless" transactions and authentications using faceprints. Despite the hyperbole in places like San Francisco, civil libertarians will not succeed in getting that cat to walk backwards.

The basis for biometric privacy protection should not be focused on anonymity, but rather obscurity. You will be increasingly subject to transparency-forcing technology, but we can legislatively mandate ways of obscuring that information. That is the objective of the Biometric Privacy Act that I have proposed in recent research. However, no such comprehensive legislation has passed through Congress.

The ability to spot fraudulent entries at airports or recognizing a felon in flight has obvious benefits for all citizens.

We also need to recognize that FRT has many beneficial uses. Biometric guns can reduce accidents and criminals' conduct. New authentications using FRT and other biometric programs could reduce identity theft.

And, yes, FRT could help protect against unnecessary police stops or false arrests. Finally, and not insignificantly, this technology could stop serious crimes, from terrorist attacks to the capturing of dangerous felons. The ability to spot fraudulent entries at airports or recognizing a felon in flight has obvious benefits for all citizens.

We can live and thrive in a biometric era. However, we will need to bring together civil libertarians with business and government experts if we are going to control this technology rather than have it control us.

[Editor's Note: Read the opposite perspective here.]