The Scientist Behind the Pap Smear Saved Countless Women from Cervical Cancer

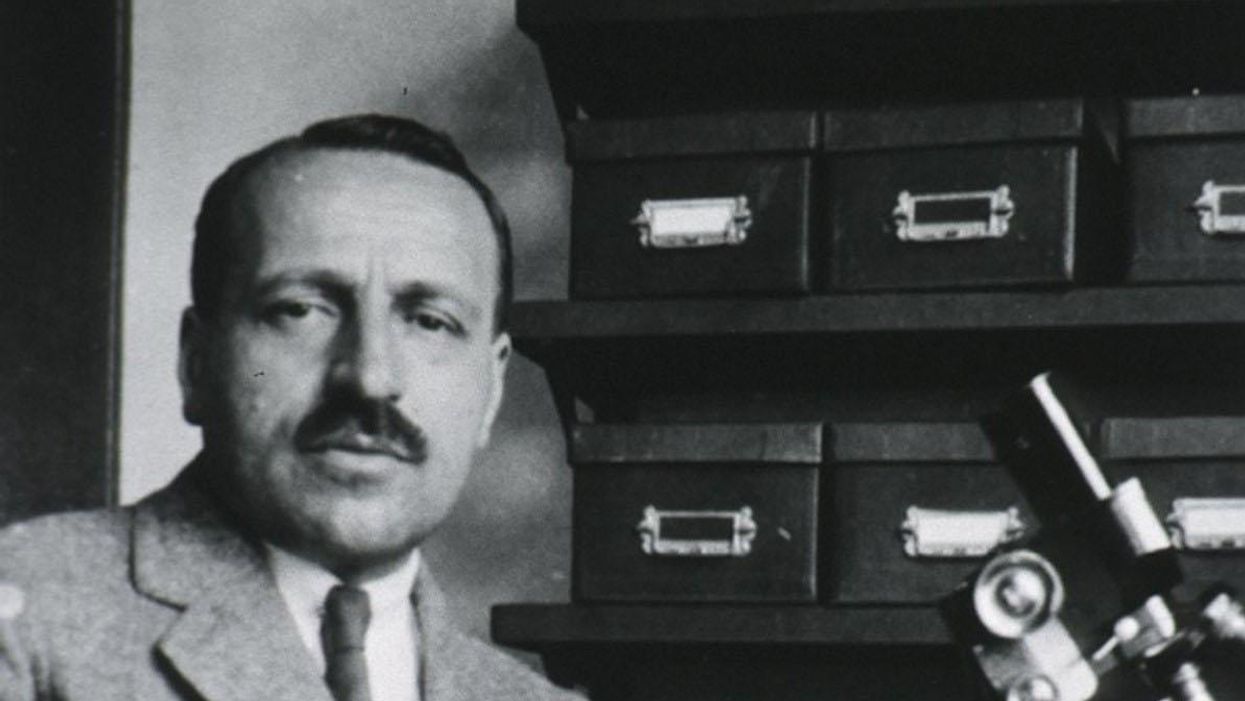

George Papanicolaou (1883-1962), Greek-born American physician developed a simple cytological test for cervical cancer in 1928.

For decades, women around the world have made the annual pilgrimage to their doctor for the dreaded but potentially life-saving Papanicolaou test, a gynecological exam to screen for cervical cancer named for Georgios Papanicolaou, the Greek immigrant who developed it.

The Pap smear, as it is commonly known, is credited for reducing cervical cancer mortality by 70% since the 1960s; the American Cancer Society (ACS) still ranks the Pap as the most successful screening test for preventing serious malignancies. Nonetheless, the agency, as well as other medical panels, including the US Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology are making a strong push to replace the Pap with the more sensitive high-risk HPV screening test for the human papillomavirus virus, which causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

So, how was the Pap developed and how did it become the gold standard of cervical cancer detection for more than 60 years?

Born on May 13, 1883, on the island of Euboea, Greece, Georgios Papanicolaou attended the University of Athens where he majored in music and the humanities before earning his medical degree in 1904 and PhD from the University of Munich six years later. In Europe, Papanicolaou was an assistant military surgeon during the Balkan War, a psychologist for an expedition of the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco and a caregiver for leprosy patients.

When he and his wife, Andromache Mavroyenous (Mary), arrived at Ellis Island on October 19, 1913, the young couple had scarcely more than the $250 minimum required to immigrate, spoke no English and had no job prospects. They worked a series of menial jobs--department store sales clerk, rug salesman, newspaper clerk, restaurant violinist--before Papanicolaou landed a position as an anatomy assistant at Cornell University and Mary was hired as his lab assistant, an arrangement that would last for the next 50 years.

Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

In his early research, Papanikolaou used guinea pigs to prove that gender is determined by the X and Y chromosomes. Using a pediatric nasal speculum, he collected and microscopically examined vaginal secretions of guinea pigs, which revealed distinct cell changes connected to the menstrual cycle. He moved on to study reproductive patterns in humans, beginning with his faithful wife, Mary, who not only endured his almost-daily cervical exams for decades, but also recruited friends as early research participants.

Writing in the medical journal Growth in 1920, the scientist outlined his theory that a microscopic smear of vaginal fluid could detect the presence of cancer cells in the uterus. Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

At this time, cervical cancer was the number one cancer killer of American women but physicians were skeptical of these new findings. They continued to rely on biopsy and curettage to diagnose and treat the disease until Papanicolaou's discovery was published in American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. An inexpensive, easy-to-perform test that could detect cervical cancer, precancerous dysplasia and other cytological diseases was a sea change. Between 1975 and 2001, the cervical cancer rate was cut in half.

Papanicolaou became Emeritus Professor at Cornell University Medical College and received numerous awards, including the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research and the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society. His image was featured on the Greek currency and the US Post Office issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. But international acclaim didn't lead to a more relaxed schedule. The researcher continued to work seven days a week and refused to take vacations.

After nearly 50 years, Papanicolaou left Cornell to head and develop the Cancer Institute of Miami. He died of a heart attack on February 19, 1962, just three months after his arrival. Mary continued to work in the renamed Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute until her death 20 years later.

The annual pap smear was originally tied to renewing a birth control prescription. Canada began recommending Pap exams every three years in 1978. The United States followed suit in 2012, noting that it takes many years for cervical cancer to develop. In September 2020, the American Cancer Society recommended delaying the first gynecological pelvic exam until age 25 and replacing the Pap test completely with the more accurate human papillomavirus (HPV) test every five years as the technology becomes more widely available.

Not everyone agrees that it's time to do away with this proven screening method, though. The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 28% higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnicities.

Whether the Pap is administered every year, every three years or not at all, Papanicolaou will always be known as the medical hero who saved countless women who would otherwise have succumbed to cervical cancer.

How the Human Brain Project Built a Mind of its Own

In 2013, the Human Brain Project set out to build a realistic computer model of the brain over ten years. Now, experts are reflecting on HBP's achievements with an eye toward the future.

In 2009, neuroscientist Henry Markram gave an ambitious TED talk. “Our mission is to build a detailed, realistic computer model of the human brain,” he said, naming three reasons for this unmatched feat of engineering. One was because understanding the human brain was essential to get along in society. Another was because experimenting on animal brains could only get scientists so far in understanding the human ones. Third, medicines for mental disorders weren’t good enough. “There are two billion people on the planet that are affected by mental disorders, and the drugs that are used today are largely empirical,” Markram said. “I think that we can come up with very concrete solutions on how to treat disorders.”

Markram's arguments were very persuasive. In 2013, the European Commission launched the Human Brain Project, or HBP, as part of its Future and Emerging Technologies program. Viewed as Europe’s chance to try to win the “brain race” between the U.S., China, Japan, and other countries, the project received about a billion euros in funding with the goal to simulate the entire human brain on a supercomputer, or in silico, by 2023.

Now, after 10 years of dedicated neuroscience research, the HBP is coming to an end. As its many critics warned, it did not manage to build an entire human brain in silico. Instead, it achieved a multifaceted array of different goals, some of them unexpected.

Scholars have found that the project did help advance neuroscience more than some detractors initially expected, specifically in the area of brain simulations and virtual models. Using an interdisciplinary approach of combining technology, such as AI and digital simulations, with neuroscience, the HBP worked to gain a deeper understanding of the human brain’s complicated structure and functions, which in some cases led to novel treatments for brain disorders. Lastly, through online platforms, the HBP spearheaded a previously unmatched level of global neuroscience collaborations.

Simulating a human brain stirs up controversy

Right from the start, the project was plagued with controversy and condemnation. One of its prominent critics was Yves Fregnac, a professor in cognitive science at the Polytechnic Institute of Paris and research director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research. Fregnac argued in numerous articles that the HBP was overfunded based on proposals with unrealistic goals. “This new way of over-selling scientific targets, deeply aligned with what modern society expects from mega-sciences in the broad sense (big investment, big return), has been observed on several occasions in different scientific sub-fields,” he wrote in one of his articles, “before invading the field of brain sciences and neuromarketing.”

"A human brain model can simulate an experiment a million times for many different conditions, but the actual human experiment can be performed only once or a few times," said Viktor Jirsa, a professor at Aix-Marseille University.

Responding to such critiques, the HBP worked to restructure the effort in its early days with new leadership, organization, and goals that were more flexible and attainable. “The HBP got a more versatile, pluralistic approach,” said Viktor Jirsa, a professor at Aix-Marseille University and one of the HBP lead scientists. He believes that these changes fixed at least some of HBP’s issues. “The project has been on a very productive and scientifically fruitful course since then.”

After restructuring, the HBP became a European hub on brain research, with hundreds of scientists joining its growing network. The HBP created projects focused on various brain topics, from consciousness to neurodegenerative diseases. HBP scientists worked on complex subjects, such as mapping out the brain, combining neuroscience and robotics, and experimenting with neuromorphic computing, a computational technique inspired by the human brain structure and function—to name just a few.

Simulations advance knowledge and treatment options

In 2013, it seemed that bringing neuroscience into a digital age would be farfetched, but research within the HBP has made this achievable. The virtual maps and simulations various HBP teams create through brain imaging data make it easier for neuroscientists to understand brain developments and functions. The teams publish these models on the HBP’s EBRAINS online platform—one of the first to offer access to such data to neuroscientists worldwide via an open-source online site. “This digital infrastructure is backed by high-performance computers, with large datasets and various computational tools,” said Lucy Xiaolu Wang, an assistant professor in the Resource Economics Department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who studies the economics of the HBP. That means it can be used in place of many different types of human experimentation.

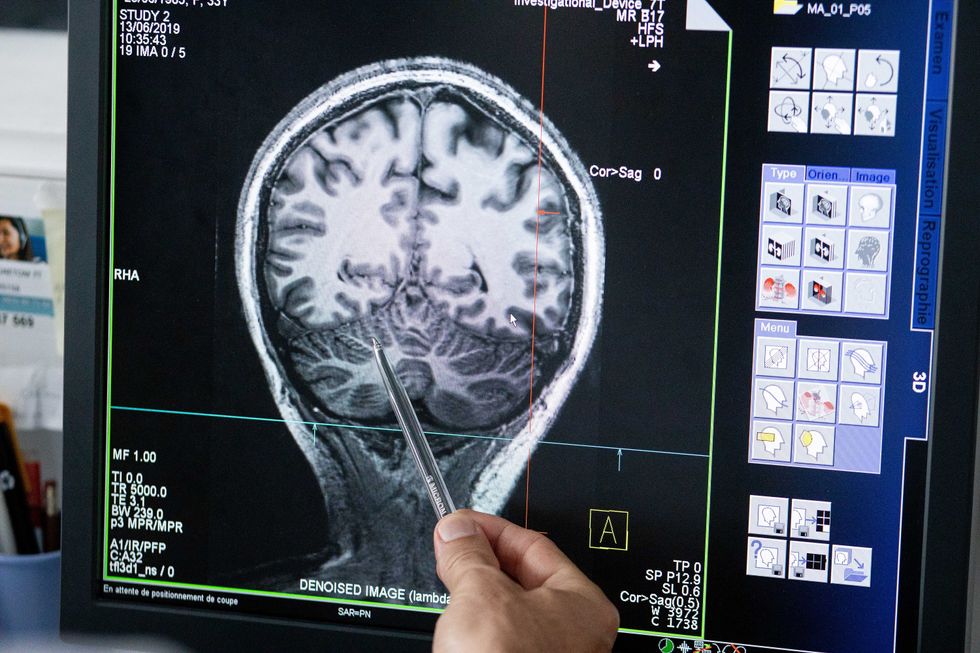

Jirsa’s team is one of many within the project that works on virtual brain models and brain simulations. Compiling patient data, Jirsa and his team can create digital simulations of different brain activities—and repeat these experiments many times, which isn’t often possible in surgeries on real brains. “A human brain model can simulate an experiment a million times for many different conditions,” Jirsa explained, “but the actual human experiment can be performed only once or a few times.” Using simulations also saves scientists and doctors time and money when looking at ways to diagnose and treat patients with brain disorders.

Compiling patient data, scientists can create digital simulations of different brain activities—and repeat these experiments many times.

The Human Brain Project

Simulations can help scientists get a full picture that otherwise is unattainable. “Another benefit is data completion,” added Jirsa, “in which incomplete data can be complemented by the model. In clinical settings, we can often measure only certain brain areas, but when linked to the brain model, we can enlarge the range of accessible brain regions and make better diagnostic predictions.”

With time, Jirsa’s team was able to move into patient-specific simulations. “We advanced from generic brain models to the ability to use a specific patient’s brain data, from measurements like MRI and others, to create individualized predictive models and simulations,” Jirsa explained. He and his team are working on this personalization technique to treat patients with epilepsy. According to the World Health Organization, about 50 million people worldwide suffer from epilepsy, a disorder that causes recurring seizures. While some epilepsy causes are known others remain an enigma, and many are hard to treat. For some patients whose epilepsy doesn’t respond to medications, removing part of the brain where seizures occur may be the only option. Understanding where in the patients’ brains seizures arise can give scientists a better idea of how to treat them and whether to use surgery versus medications.

“We apply such personalized models…to precisely identify where in a patient’s brain seizures emerge,” Jirsa explained. “This guides individual surgery decisions for patients for which surgery is the only treatment option.” He credits the HBP for the opportunity to develop this novel approach. “The personalization of our epilepsy models was only made possible by the Human Brain Project, in which all the necessary tools have been developed. Without the HBP, the technology would not be in clinical trials today.”

Personalized simulations can significantly advance treatments, predict the outcome of specific medical procedures and optimize them before actually treating patients. Jirsa is watching this happen firsthand in his ongoing research. “Our technology for creating personalized brain models is now used in a large clinical trial for epilepsy, funded by the French state, where we collaborate with clinicians in hospitals,” he explained. “We have also founded a spinoff company called VB Tech (Virtual Brain Technologies) to commercialize our personalized brain model technology and make it available to all patients.”

The Human Brain Project created a level of interconnectedness within the neuroscience research community that never existed before—a network not unlike the brain’s own.

Other experts believe it’s too soon to tell whether brain simulations could change epilepsy treatments. “The life cycle of developing treatments applicable to patients often runs over a decade,” Wang stated. “It is still too early to draw a clear link between HBP’s various project areas with patient care.” However, she admits that some studies built on the HBP-collected knowledge are already showing promise. “Researchers have used neuroscientific atlases and computational tools to develop activity-specific stimulation programs that enabled paraplegic patients to move again in a small-size clinical trial,” Wang said. Another intriguing study looked at simulations of Alzheimer’s in the brain to understand how it evolves over time.

Some challenges remain hard to overcome even with computer simulations. “The major challenge has always been the parameter explosion, which means that many different model parameters can lead to the same result,” Jirsa explained. An example of this parameter explosion could be two different types of neurodegenerative conditions, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases. Both afflict the same area of the brain, the basal ganglia, which can affect movement, but are caused by two different underlying mechanisms. “We face the same situation in the living brain, in which a large range of diverse mechanisms can produce the same behavior,” Jirsa said. The simulations still have to overcome the same challenge.

Understanding where in the patients’ brains seizures arise can give scientists a better idea of how to treat them and whether to use surgery versus medications.

The Human Brain Project

A network not unlike the brain’s own

Though the HBP will be closing this year, its legacy continues in various studies, spin-off companies, and its online platform, EBRAINS. “The HBP is one of the earliest brain initiatives in the world, and the 10-year long-term goal has united many researchers to collaborate on brain sciences with advanced computational tools,” Wang said. “Beyond the many research articles and projects collaborated on during the HBP, the online neuroscience research infrastructure EBRAINS will be left as a legacy even after the project ends.”

Those who worked within the HBP see the end of this project as the next step in neuroscience research. “Neuroscience has come closer to very meaningful applications through the systematic link with new digital technologies and collaborative work,” Jirsa stated. “In that way, the project really had a pioneering role.” It also created a level of interconnectedness within the neuroscience research community that never existed before—a network not unlike the brain’s own. “Interconnectedness is an important advance and prerequisite for progress,” Jirsa said. “The neuroscience community has in the past been rather fragmented and this has dramatically changed in recent years thanks to the Human Brain Project.”

According to its website, by 2023 HBP’s network counted over 500 scientists from over 123 institutions and 16 different countries, creating one of the largest multi-national research groups in the world. Even though the project hasn’t produced the in-silico brain as Markram envisioned it, the HBP created a communal mind with immense potential. “It has challenged us to think beyond the boundaries of our own laboratories,” Jirsa said, “and enabled us to go much further together than we could have ever conceived going by ourselves.”

Regenerative medicine has come a long way, baby

After a cloned baby sheep, what started as one of the most controversial areas in medicine is now promising to transform it.

The field of regenerative medicine had a shaky start. In 2002, when news spread about the first cloned animal, Dolly the sheep, a raucous debate ensued. Scary headlines and organized opposition groups put pressure on government leaders, who responded by tightening restrictions on this type of research.

Fast forward to today, and regenerative medicine, which focuses on making unhealthy tissues and organs healthy again, is rewriting the code to healing many disorders, though it’s still young enough to be considered nascent. What started as one of the most controversial areas in medicine is now promising to transform it.

Progress in the lab has addressed previous concerns. Back in the early 2000s, some of the most fervent controversy centered around somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), the process used by scientists to produce Dolly. There was fear that this technique could be used in humans, with possibly adverse effects, considering the many medical problems of the animals who had been cloned.

But today, scientists have discovered better approaches with fewer risks. Pioneers in the field are embracing new possibilities for cellular reprogramming, 3D organ printing, AI collaboration, and even growing organs in space. It could bring a new era of personalized medicine for longer, healthier lives - while potentially sparking new controversies.

Engineering tissues from amniotic fluids

Work in regenerative medicine seeks to reverse damage to organs and tissues by culling, modifying and replacing cells in the human body. Scientists in this field reach deep into the mechanisms of diseases and the breakdowns of cells, the little workhorses that perform all life-giving processes. If cells can’t do their jobs, they take whole organs and systems down with them. Regenerative medicine seeks to harness the power of healthy cells derived from stem cells to do the work that can literally restore patients to a state of health—by giving them healthy, functioning tissues and organs.

Modern-day regenerative medicine takes its origin from the 1998 isolation of human embryonic stem cells, first achieved by John Gearhart at Johns Hopkins University. Gearhart isolated the pluripotent cells that can differentiate into virtually every kind of cell in the human body. There was a raging controversy about the use of these cells in research because at that time they came exclusively from early-stage embryos or fetal tissue.

Back then, the highly controversial SCNT cells were the only way to produce genetically matched stem cells to treat patients. Since then, the picture has changed radically because other sources of highly versatile stem cells have been developed. Today, scientists can derive stem cells from amniotic fluid or reprogram patients’ skin cells back to an immature state, so they can differentiate into whatever types of cells the patient needs.

In the context of medical history, the field of regenerative medicine is progressing at a dizzying speed. But for those living with aggressive or chronic illnesses, it can seem that the wheels of medical progress grind slowly.

The ethical debate has been dialed back and, in the last few decades, the field has produced important innovations, spurring the development of whole new FDA processes and categories, says Anthony Atala, a bioengineer and director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Atala and a large team of researchers have pioneered many of the first applications of 3D printed tissues and organs using cells developed from patients or those obtained from amniotic fluid or placentas.

His lab, considered to be the largest devoted to translational regenerative medicine, is currently working with 40 different engineered human tissues. Sixteen of them have been transplanted into patients. That includes skin, bladders, urethras, muscles, kidneys and vaginal organs, to name just a few.

These achievements are made possible by converging disciplines and technologies, such as cell therapies, bioengineering, gene editing, nanotechnology and 3D printing, to create living tissues and organs for human transplants. Atala is currently overseeing clinical trials to test the safety of tissues and organs engineered in the Wake Forest lab, a significant step toward FDA approval.

In the context of medical history, the field of regenerative medicine is progressing at a dizzying speed. But for those living with aggressive or chronic illnesses, it can seem that the wheels of medical progress grind slowly.

“It’s never fast enough,” Atala says. “We want to get new treatments into the clinic faster, but the reality is that you have to dot all your i’s and cross all your t’s—and rightly so, for the sake of patient safety. People want predictions, but you can never predict how much work it will take to go from conceptualization to utilization.”

As a surgeon, he also treats patients and is able to follow transplant recipients. “At the end of the day, the goal is to get these technologies into patients, and working with the patients is a very rewarding experience,” he says. Will the 3D printed organs ever outrun the shortage of donated organs? “That’s the hope,” Atala says, “but this technology won’t eliminate the need for them in our lifetime.”

New methods are out of this world

Jeanne Loring, another pioneer in the field and director of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Scripps Research Institute in San Diego, says that investment in regenerative medicine is not only paying off, but is leading to truly personalized medicine, one of the holy grails of modern science.

This is because a patient’s own skin cells can be reprogrammed to become replacements for various malfunctioning cells causing incurable diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, macular degeneration and Parkinson’s. If the cells are obtained from a source other than the patient, they can be rejected by the immune system. This means that patients need lifelong immunosuppression, which isn’t ideal. “With Covid,” says Loring, “I became acutely aware of the dangers of immunosuppression.” Using the patient’s own cells eliminates that problem.

Microgravity conditions make it easier for the cells to form three-dimensional structures, which could more easily lead to the growing of whole organs. In fact, Loring's own cells have been sent to the ISS for study.

Loring has a special interest in neurons, or brain cells that can be developed by manipulating cells found in the skin. She is looking to eventually treat Parkinson’s disease using them. The manipulated cells produce dopamine, the critical hormone or neurotransmitter lacking in the brains of patients. A company she founded plans to start a Phase I clinical trial using cell therapies for Parkinson’s soon, she says.

This is the culmination of many years of basic research on her part, some of it on her own cells. In 2007, Loring had her own cells reprogrammed, so there’s a cell line that carries her DNA. “They’re just like embryonic stem cells, but personal,” she said.

Loring has another special interest—sending immature cells into space to be studied at the International Space Station. There, microgravity conditions make it easier for the cells to form three-dimensional structures, which could more easily lead to the growing of whole organs. In fact, her own cells have been sent to the ISS for study. “My colleagues and I have completed four missions at the space station,” she says. “The last cells came down last August. They were my own cells reprogrammed into pluripotent cells in 2009. No one else can say that,” she adds.

Future controversies and tipping points

Although the original SCNT debate has calmed down, more controversies may arise, Loring thinks.

One of them could concern growing synthetic embryos. The embryos are ultimately derived from embryonic stem cells, and it’s not clear to what stage these embryos can or will be grown in an artificial uterus—another recent invention. The science, so far done only in animals, is still new and has not been widely publicized but, eventually, “People will notice the production of synthetic embryos and growing them in an artificial uterus,” Loring says. It’s likely to incite many of the same reactions as the use of embryonic stem cells.

Bernard Siegel, the founder and director of the Regenerative Medicine Foundation and executive director of the newly formed Healthspan Action Coalition (HSAC), believes that stem cell science is rapidly approaching tipping point and changing all of medical science. (For disclosure, I do consulting work for HSAC). Siegel says that regenerative medicine has become a new pillar of medicine that has recently been fast-tracked by new technology.

Artificial intelligence is speeding up discoveries and the convergence of key disciplines, as demonstrated in Atala’s lab, which is creating complex new medical products that replace the body’s natural parts. Just as importantly, those parts are genetically matched and pose no risk of rejection.

These new technologies must be regulated, which can be a challenge, Siegel notes. “Cell therapies represent a challenge to the existing regulatory structure, including payment, reimbursement and infrastructure issues that 20 years ago, didn’t exist.” Now the FDA and other agencies are faced with this revolution, and they’re just beginning to adapt.

Siegel cited the 2021 FDA Modernization Act as a major step. The Act allows drug developers to use alternatives to animal testing in investigating the safety and efficacy of new compounds, loosening the agency’s requirement for extensive animal testing before a new drug can move into clinical trials. The Act is a recognition of the profound effect that cultured human cells are having on research. Being able to test drugs using actual human cells promises to be far safer and more accurate in predicting how they will act in the human body, and could accelerate drug development.

Siegel, a longtime veteran and founding father of several health advocacy organizations, believes this work helped bring cell therapies to people sooner rather than later. His new focus, through the HSAC, is to leverage regenerative medicine into extending not just the lifespan but the worldwide human healthspan, the period of life lived with health and vigor. “When you look at the HSAC as a tree,” asks Siegel, “what are the roots of that tree? Stem cell science and the huge ecosystem it has created.” The study of human aging is another root to the tree that has potential to lengthen healthspans.

The revolutionary science underlying the extension of the healthspan needs to be available to the whole world, Siegel says. “We need to take all these roots and come up with a way to improve the life of all mankind,” he says. “Everyone should be able to take advantage of this promising new world.”