Her Incredible Sense of Smell Helped Scientists Develop the First Parkinson's Test

Joy Milne's unusual sense of smell led Dr. Tilo Kunath, a neurobiologist at the Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, and a host of other scientists, to develop a new diagnostic test for Parkinson's.

Forty years ago, Joy Milne, a nurse from Perth, Scotland, noticed a musky odor coming from her husband, Les. At first, Milne thought the smell was a result of bad hygiene and badgered her husband to take longer showers. But when the smell persisted, Milne learned to live with it, not wanting to hurt her husband's feelings.

Twelve years after she first noticed the "woodsy" smell, Les was diagnosed at the age of 44 with Parkinson's Disease, a neurodegenerative condition characterized by lack of dopamine production and loss of movement. Parkinson's Disease currently affects more than 10 million people worldwide.

Milne spent the next several years believing the strange smell was exclusive to her husband. But to her surprise, at a local support group meeting in 2012, she caught the familiar scent once again, hanging over the group like a cloud. Stunned, Milne started to wonder if the smell was the result of Parkinson's Disease itself.

Milne's discovery led her to Dr. Tilo Kunath, a neurobiologist at the Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh. Together, Milne, Kunath, and a host of other scientists would use Milne's unusual sense of smell to develop a new diagnostic test, now in development and poised to revolutionize the treatment of Parkinson's Disease.

"Joy was in the audience during a talk I was giving on my work, which has to do with Parkinson's and stem cell biology," Kunath says. "During the patient engagement portion of the talk, she asked me if Parkinson's had a smell to it." Confused, Kunath said he had never heard of this – but for months after his talk he continued to turn the question over in his mind.

Kunath knew from his research that the skin's microbiome changes during different disease processes, releasing metabolites that can give off odors. In the medical literature, diseases like melanoma and Type 2 diabetes have been known to carry a specific scent – but no such connection had been made with Parkinson's. If people could smell Parkinson's, he thought, then it stood to reason that those metabolites could be isolated, identified, and used to potentially diagnose Parkinson's by their presence alone.

First, Kunath and his colleagues decided to test Milne's sense of smell. "I got in touch with Joy again and we designed a protocol to test her sense of smell without her having to be around patients," says Kunath, which could have affected the validity of the test. In his spare time, Kunath collected t-shirt samples from people diagnosed with Parkinson's and from others without the diagnosis and gave them to Milne to smell. In 100 percent of the samples, Milne was able to detect whether a person had Parkinson's based on smell alone. Amazingly, Milne was even able to detect the "Parkinson's scent" in a shirt from the control group – someone who did not have a Parkinson's diagnosis, but would go on to be diagnosed nine months later.

From the initial study, the team discovered that Parkinson's did have a smell, that Milne – inexplicably – could detect it, and that she could detect it long before diagnosis like she had with her husband, Les. But the experiments revealed other things that the team hadn't been expecting.

"One surprising thing we learned from that experiment was that the odor was always located in the back of the shirt – never in the armpit, where we expected the smell to be," Kunath says. "I had a chance meeting with a dermatologist and he said the smell was due to the patient's sebum, which are greasy secretions that are really dense on your upper back. We have sweat glands, instead of sebum, in our armpits." Patients with Parkinson's are also known to have increased sebum production.

With the knowledge that a patient's sebum was the source of the unusual smell, researchers could go on to investigate exactly what metabolites were in the sebum and in what amounts. Kunath, along with his associate, Dr. Perdita Barran, collected and analyzed sebum samples from 64 participants across the United Kingdom. Once the samples were collected, Barran and others analyzed it using a method called gas chromatography mass spectrometry, or GS-MC, which separated, weighed and helped identify the individual compounds present in each sebum sample.

Barran's team can now correctly identify Parkinson's in nine out of 10 patients – a much quicker and more accurate way to diagnose than what clinicians do now.

"The compounds we've identified in the sebum are not unique to people with Parkinson's, but they are differently expressed," says Barran, a professor of mass spectrometry at the University of Manchester. "So this test we're developing now is not a black-and-white, do-you-have-something kind of test, but rather how much of these compounds do you have compared to other people and other compounds." The team identified over a dozen compounds that were present in the sebum of Parkinson's patients in much larger amounts than the control group.

Using only the GC-MS and a sebum swab test, Barran's team can now correctly identify Parkinson's in nine out of 10 patients – a much quicker and more accurate way to diagnose than what clinicians do now.

"At the moment, a clinical diagnosis is based on the patient's physical symptoms," Barran says, and determining whether a patient has Parkinson's is often a long and drawn-out process of elimination. "Doctors might say that a group of symptoms looks like Parkinson's, but there are other reasons people might have those symptoms, and it might take another year before they're certain," Barran says. "Some of those symptoms are just signs of aging, and other symptoms like tremor are present in recovering alcoholics or people with other kinds of dementia." People under the age of 40 with Parkinson's symptoms, who present with stiff arms, are often misdiagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome, she adds.

Additionally, by the time physical symptoms are present, Parkinson's patients have already lost a substantial amount of dopamine receptors – about sixty percent -- in the brain's basal ganglia. Getting a diagnosis before physical symptoms appear would mean earlier interventions that could prevent dopamine loss and preserve regular movement, Barran says.

"Early diagnosis is good if it means there's a chance of early intervention," says Barran. "It stops the process of dopamine loss, which means that motor symptoms potentially will not happen, or the onset of symptoms will be substantially delayed." Barran's team is in the processing of streamlining the sebum test so that definitive results will be ready in just two minutes.

"What we're doing right now will be a very inexpensive test, a rapid-screen test, and that will encourage people to self-sample and test at home," says Barran. In addition to diagnosing Parkinson's, she says, this test could also be potentially useful to determine if medications were at a therapeutic dose in people who have the disease, since the odor is strongest in people whose symptoms are least controlled by medication.

"When symptoms are under control, the odor is lower," Barran says. "Potentially this would allow patients and clinicians to see whether their symptoms are being managed properly with medication, or perhaps if they're being overmedicated." Hypothetically, patients could also use the test to determine if interventions like diet and exercise are effective at keeping Parkinson's controlled.

"We hope within the next two to five years we will have a test available."

Barran is now running another clinical trial – one that determines whether they can diagnose at an earlier stage and whether they can identify a difference in sebum samples between different forms of Parkinson's or diseases that have Parkinson's-like symptoms, such as Lewy Body Dementia.

"Within the next one to two years, we hope to be running a trial in the Manchester area for those people who do not have motor symptoms but are at risk for developing dementia due to symptoms like loss of smell and sleep difficulty," Barran had said in 2019. "If we can establish that, we can roll out a test that determines if you have Parkinson's or not with those first pre-motor symptoms, and then at what stage. We hope within the next two to five years we will have a test available."

In a 2022 study, published in the American Chemical Society, researchers used mass spectrometry to analyze sebum from skin swabs for the presence of the specific molecules. They found that some specific molecules are present only in people who have Parkinson’s. Now they hope that the same method can be used in regular diagnostic labs. The test, many years in the making, is inching its way to the clinic.

"We would likely first give this test to people who are at risk due to a genetic predisposition, or who are at risk based on prodomal symptoms, like people who suffer from a REM sleep disorder who have a 50 to 70 percent chance of developing Parkinson's within a ten year period," Barran says. "Those would be people who would benefit from early therapeutic intervention. For the normal population, it isn't beneficial at the moment to know until we have therapeutic interventions that can be useful."

Milne's husband, Les, passed away from complications of Parkinson's Disease in 2015. But thanks to him and the dedication of his wife, Joy, science may have found a way to someday prolong the lives of others with this devastating disease. Sometimes she can smell people who have Parkinson’s while in the supermarket or walking down the street but has been told by medical ethicists she cannot tell them, Milne said in an interview with the Guardian. But once the test becomes available in the clinics, it will do the job for her.

[Ed. Note: A older version of this hit article originally ran on September 3, 2019.]

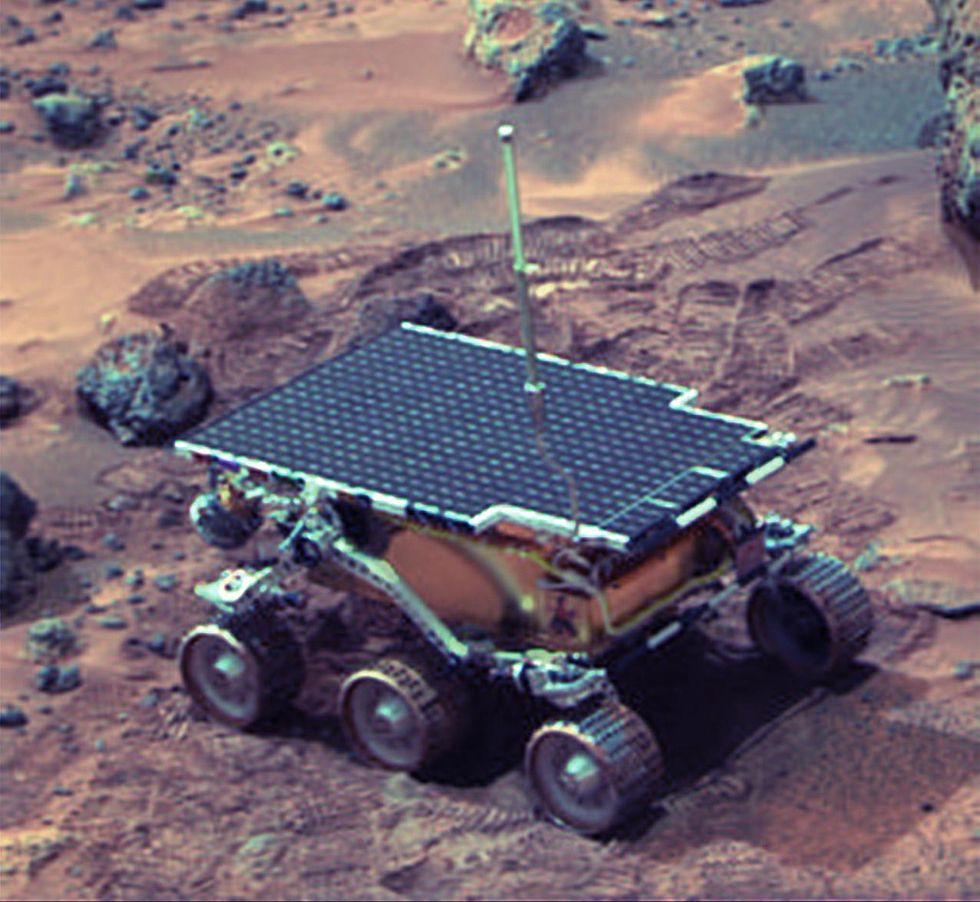

Donna Shirley pictured at her home in Tulsa, with a model of the Sojourner rover she was in charge of that explored Mars.

When NASA's Perseverance rover landed successfully on Mars on February 18, 2021, calling it "one giant leap for mankind" – as Neil Armstrong said when he set foot on the moon in 1969 – would have been inaccurate. This year actually marked the fifth time the U.S. space agency has put a remote-controlled robotic exploration vehicle on the Red Planet. And it was a female engineer named Donna Shirley who broke new ground for women in science as the manager of both the Mars Exploration Program and the 30-person team that built Sojourner, the first rover to land on Mars on July 4, 1997.

For Shirley, the Mars Pathfinder mission was the climax of her 32-year career at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. The Oklahoma-born scientist, who earned her Master's degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Southern California, saw her profile skyrocket with media appearances from CNN to the New York Times, and her autobiography Managing Martians came out in 1998. Now 79 and living in a Tulsa retirement community, she still embraces her status as a female pioneer.

"Periodically, I'll hear somebody say they got into the space program because of me, and that makes me feel really good," Shirley told Leaps.org. "I look at the mission control area, and there are a lot of women in there. I'm quite pleased I was able to break the glass ceiling."

Her $25-million, 25-pound microrover – powered by solar energy and designed to get rock samples and test soil chemistry for evidence of life – was named after Sojourner Truth, a 19th-century Black abolitionist and women's rights activist. Unlike Mars Pathfinder, Shirley didn't have to travel more than 131 million miles to reach her goal, but her path to scientific fame as a woman sometimes resembled an asteroid field.

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.

NASA/JPL

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.

NASA/JPL

As a high-IQ tomboy growing up in Wynnewood, Oklahoma (pop. 2,300), Shirley yearned to escape. She decided to become an engineer at age 10 and took flying lessons at 15. Her extraterrestrial aspirations were fueled by Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles and Arthur C. Clarke's The Sands of Mars. Yet when she entered the University of Oklahoma (OU) in 1958, her freshman academic advisor initially told her: "Girls can't be engineers." She ignored him.

Years later, Shirley would combat such archaic thinking, succeeding at JPL with her creative, collaborative management style. "If you look at the literature, you'll find that teams that are either led by or heavily involved with women do better than strictly male teams," she noted.

However, her career trajectory stalled at OU. Burned out by her course load and distracted by a broken engagement to marry a fellow student, she switched her major to professional writing. After graduation, she applied her aeronautical background as a McDonnell Aircraft technical writer, but her boss, she says, harassed her and she faced gender-based hostility from male co-workers.

Returning to OU, Shirley finished off her engineering degree and became a JPL aerodynamist in 1966 after answering an ad in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. At first, she was the only female engineer among the research center's 2,000-odd engineers. She wore many hats, from designing planetary atmospheric entry vehicles to picking the launch date of November 4, 1973 for Mariner 10's mission to Venus and Mercury.

By the mid-1980's, she was managing teams that focused on robotics and Mars, delivering creative solutions when NASA budget cuts loomed. In 1989, the same year the Sojourner microrover concept was born, President George H.W. Bush announced his Space Exploration Initiative, including plans for a human mission to Mars by 2019.

That target, of course, wasn't attained, despite huge advances in technology and our understanding of the Martian environment. Today, Shirley believes humans could land on Mars by 2030. She became the founding director of the Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle in 2004 after leaving NASA, and to this day, she enjoys checking out pop culture portrayals of Mars landings – even if they're not always accurate.

After the novel The Martian was published in 2011, which later was adapted into the hit film starring Matt Damon, Shirley phoned author Andy Weir: "You've got a major mistake in here. It says there's a storm that tries to blow the rocket over. But actually, the Mars atmosphere is so thin, it would never blow a rocket over!"

Fearlessly speaking her mind and seeking the stars helped Donna Shirley make history. However, a 2019 Washington Post story noted: "Women make up only about a third of NASA's workforce. They comprise just 28 percent of senior executive leadership positions and are only 16 percent of senior scientific employees." Whether it's traveling to Mars or trending toward gender equality, we've still got a long way to go.

Announcing March Event: "COVID Vaccines and the Return to Life: Part 1"

Leading medical and scientific experts will discuss the latest developments around the COVID-19 vaccines at our March 11th event.

EVENT INFORMATION

DATE:

Thursday, March 11th, 2021 at 12:30pm - 1:45pm EST

On the one-year anniversary of the global declaration of the pandemic, this virtual event will convene leading scientific and medical experts to discuss the most pressing questions around the COVID-19 vaccines. Planned topics include the effect of the new circulating variants on the vaccines, what we know so far about transmission dynamics post-vaccination, how individuals can behave post-vaccination, the myths of "good" and "bad" vaccines as more alternatives come on board, and more. A public Q&A will follow the expert discussion.

CONTACT:

kira@goodinc.com

LOCATION:

Zoom webinar

SPEAKERS:

Dr. Paul Offit speaking at Communicating Vaccine Science.

commons.wikimedia.orgDr. Paul Offit, M.D., is the director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in infectious diseases at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. He is a co-inventor of the rotavirus vaccine for infants, and he has lent his expertise to the advisory committees that review data on new vaccines for the CDC and FDA.

Dr. Monica Gandhi

UCSF Health

Dr. Monica Gandhi, M.D., MPH, is Professor of Medicine and Associate Division Chief (Clinical Operations/ Education) of the Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases, and Global Medicine at UCSF/ San Francisco General Hospital.

Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu, MBBCh, FACP, FIDSA

Yale Medicine

Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu, MBBCh, is an infectious disease physician at Yale Medicine who treats COVID-19 patients and leads Yale's clinical studies around COVID-19. He ran Yale's trial of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

Dr. Eric Topol

Dr. Topol's Twitter

Dr. Eric Topol, M.D., is a cardiologist, scientist, professor of molecular medicine, and the director and founder of Scripps Research Translational Institute. He has led clinical trials in over 40 countries with over 200,000 patients and pioneered the development of many routinely used medications.

REGISTER NOW

This event is the first of a four-part series co-hosted by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.