How a Deadly Fire Gave Birth to Modern Medicine

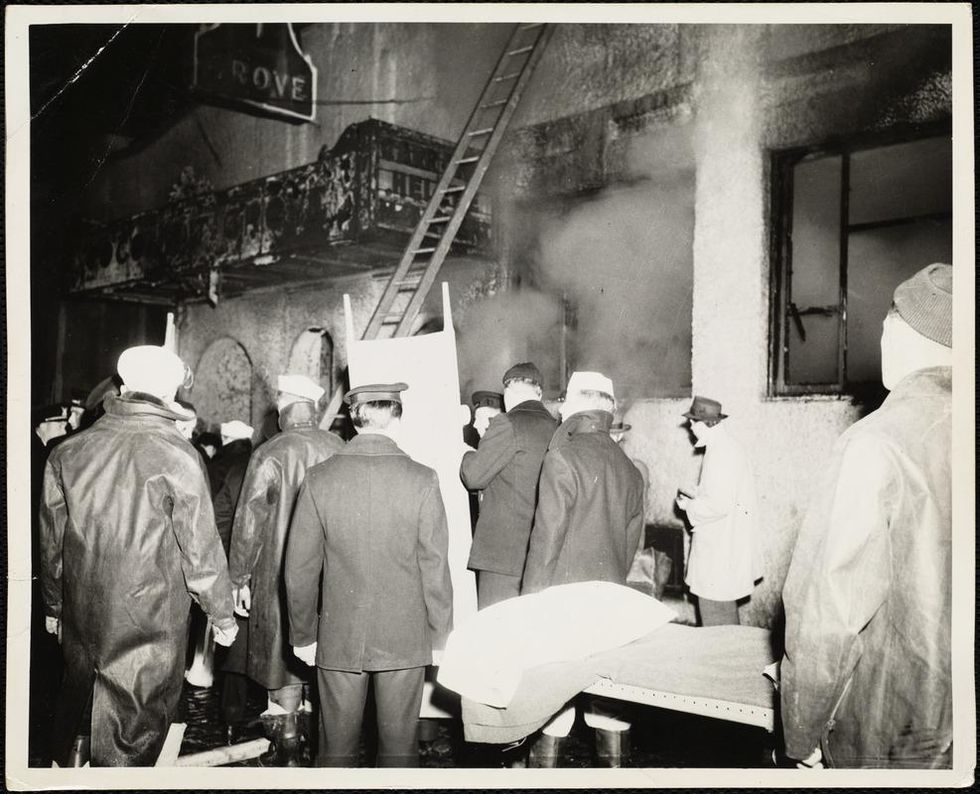

The Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston in 1942 tragically claimed 490 lives, but was the catalyst for several important medical advances.

On the evening of November 28, 1942, more than 1,000 revelers from the Boston College-Holy Cross football game jammed into the Cocoanut Grove, Boston's oldest nightclub. When a spark from faulty wiring accidently ignited an artificial palm tree, the packed nightspot, which was only designed to accommodate about 500 people, was quickly engulfed in flames. In the ensuing panic, hundreds of people were trapped inside, with most exit doors locked. Bodies piled up by the only open entrance, jamming the exits, and 490 people ultimately died in the worst fire in the country in forty years.

"People couldn't get out," says Dr. Kenneth Marshall, a retired plastic surgeon in Boston and president of the Cocoanut Grove Memorial Committee. "It was a tragedy of mammoth proportions."

Within a half an hour of the start of the blaze, the Red Cross mobilized more than five hundred volunteers in what one newspaper called a "Rehearsal for Possible Blitz." The mayor of Boston imposed martial law. More than 300 victims—many of whom subsequently died--were taken to Boston City Hospital in one hour, averaging one victim every eleven seconds, while Massachusetts General Hospital admitted 114 victims in two hours. In the hospitals, 220 victims clung precariously to life, in agonizing pain from massive burns, their bodies ravaged by infection.

The scene of the fire.

Boston Public Library

Tragic Losses Prompted Revolutionary Leaps

But there is a silver lining: this horrific disaster prompted dramatic changes in safety regulations to prevent another catastrophe of this magnitude and led to the development of medical techniques that eventually saved millions of lives. It transformed burn care treatment and the use of plasma on burn victims, but most importantly, it introduced to the public a new wonder drug that revolutionized medicine, midwifed the birth of the modern pharmaceutical industry, and nearly doubled life expectancy, from 48 years at the turn of the 20th century to 78 years in the post-World War II years.

The devastating grief of the survivors also led to the first published study of post-traumatic stress disorder by pioneering psychiatrist Alexandra Adler, daughter of famed Viennese psychoanalyst Alfred Adler, who was a student of Freud. Dr. Adler studied the anxiety and depression that followed this catastrophe, according to the New York Times, and "later applied her findings to the treatment World War II veterans."

Dr. Ken Marshall is intimately familiar with the lingering psychological trauma of enduring such a disaster. His mother, an Irish immigrant and a nurse in the surgical wards at Boston City Hospital, was on duty that cold Thanksgiving weekend night, and didn't come home for four days. "For years afterward, she'd wake up screaming in the middle of the night," recalls Dr. Marshall, who was four years old at the time. "Seeing all those bodies lined up in neat rows across the City Hospital's parking lot, still in their evening clothes. It was always on her mind and memories of the horrors plagued her for the rest of her life."

The sheer magnitude of casualties prompted overwhelmed physicians to try experimental new procedures that were later successfully used to treat thousands of battlefield casualties. Instead of cutting off blisters and using dyes and tannic acid to treat burned tissues, which can harden the skin, they applied gauze coated with petroleum jelly. Doctors also refined the formula for using plasma--the fluid portion of blood and a medical technology that was just four years old--to replenish bodily liquids that evaporated because of the loss of the protective covering of skin.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance. And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

"The initial insult with burns is a loss of fluids and patients can die of shock," says Dr. Ken Marshall. "The scientific progress that was made by the two institutions revolutionized fluid management and topical management of burn care forever."

Still, they could not halt the staph infections that kill most burn victims—which prompted the first civilian use of a miracle elixir that was being secretly developed in government-sponsored labs and that ultimately ushered in a new age in therapeutics. Military officials quickly realized this disaster could provide an excellent natural laboratory to test the effectiveness of this drug and see if it could be used to treat the acute traumas of combat in this unfortunate civilian approximation of battlefield conditions. At the time, the very existence of this wondrous medicine—penicillin—was a closely guarded military secret.

From Forgotten Lab Experiment to Wonder Drug

In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered the curative powers of penicillin, which promised to eradicate infectious pathogens that killed millions every year. But the road to mass producing enough of the highly unstable mold was littered with seemingly unsurmountable obstacles and it remained a forgotten laboratory curiosity for over a decade. But Fleming never gave up and penicillin's eventual rescue from obscurity was a landmark in scientific history.

In 1940, a group at Oxford University, funded in part by the Rockefeller Foundation, isolated enough penicillin to test it on twenty-five mice, which had been infected with lethal doses of streptococci. Its therapeutic effects were miraculous—the untreated mice died within hours, while the treated ones played merrily in their cages, undisturbed. Subsequent tests on a handful of patients, who were brought back from the brink of death, confirmed that penicillin was indeed a wonder drug. But Britain was then being ravaged by the German Luftwaffe during the Blitz, and there were simply no resources to devote to penicillin during the Nazi onslaught.

In June of 1941, two of the Oxford researchers, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, embarked on a clandestine mission to enlist American aid. Samples of the temperamental mold were stored in their coats. By October, the Roosevelt Administration had recruited four companies—Merck, Squibb, Pfizer and Lederle—to team up in a massive, top-secret development program. Merck, which had more experience with fermentation procedures, swiftly pulled away from the pack and every milligram they produced was zealously hoarded.

After the nightclub fire, the government ordered Merck to dispatch to Boston whatever supplies of penicillin that they could spare and to refine any crude penicillin broth brewing in Merck's fermentation vats. After working in round-the-clock relays over the course of three days, on the evening of December 1st, 1942, a refrigerated truck containing thirty-two liters of injectable penicillin left Merck's Rahway, New Jersey plant. It was accompanied by a convoy of police escorts through four states before arriving in the pre-dawn hours at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dozens of people were rescued from near-certain death in the first public demonstration of the powers of the antibiotic, and the existence of penicillin could no longer be kept secret from inquisitive reporters and an exultant public. The next day, the Boston Globe called it "priceless" and Time magazine dubbed it a "wonder drug."

Within fourteen months, penicillin production escalated exponentially, churning out enough to save the lives of thousands of soldiers, including many from the Normandy invasion. And in October 1945, just weeks after the Japanese surrender ended World War II, Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain were awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine. But penicillin didn't just save lives—it helped build some of the most innovative medical and scientific companies in history, including Merck, Pfizer, Glaxo and Sandoz.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance," concludes Marshall. "And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

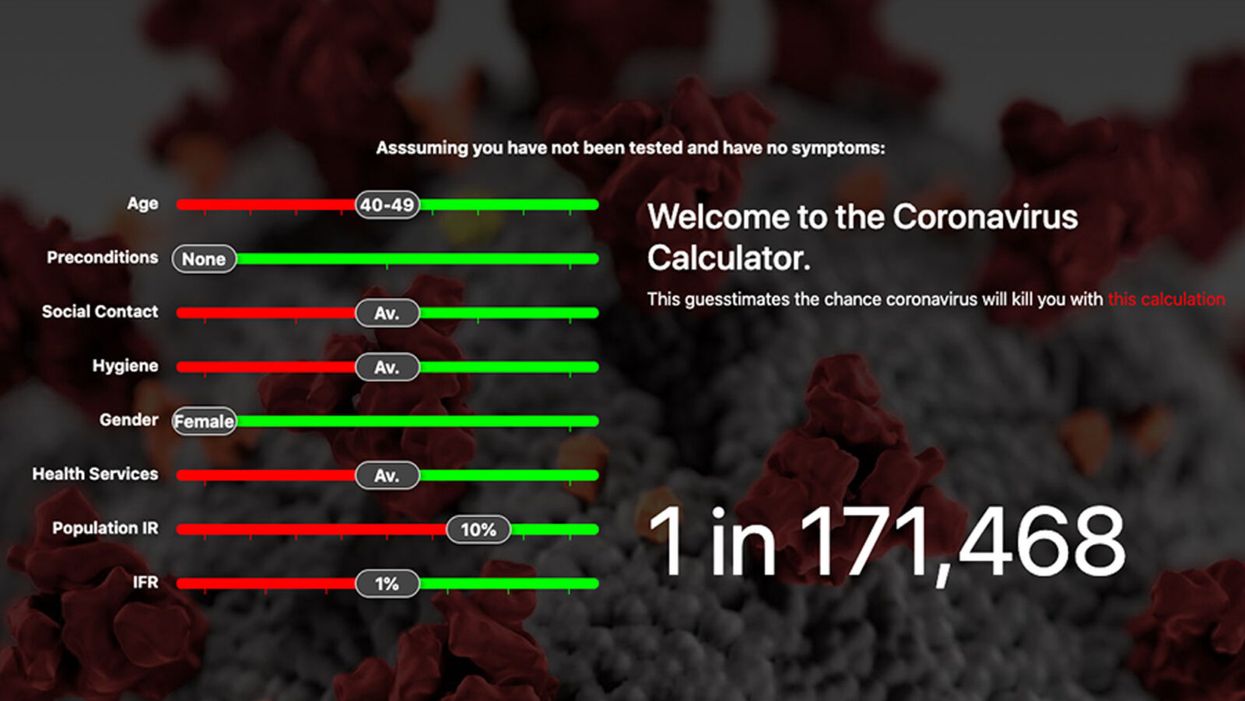

Coronavirus Risk Calculators: What You Need to Know

A screenshot of one coronavirus risk calculator.

People in my family seem to develop every ailment in the world, including feline distemper and Dutch elm disease, so I naturally put fingers to keyboard when I discovered that COVID-19 risk calculators now exist.

"It's best to look at your risk band. This will give you a more useful insight into your personal risk."

But the results – based on my answers to questions -- are bewildering.

A British risk calculator developed by the Nexoid software company declared I have a 5 percent, or 1 in 20, chance of developing COVID-19 and less than 1 percent risk of dying if I get it. Um, great, I think? Meanwhile, 19 and Me, a risk calculator created by data scientists, says my risk of infection is 0.01 percent per week, or 1 in 10,000, and it gave me a risk score of 44 out of 100.

Confused? Join the club. But it's actually possible to interpret numbers like these and put them to use. Here are five tips about using coronavirus risk calculators:

1. Make Sure the Calculator Is Designed For You

Not every COVID-19 risk calculator is designed to be used by the general public. Cleveland Clinic's risk calculator, for example, is only a tool for medical professionals, not sick people or the "worried well," said Dr. Lara Jehi, Cleveland Clinic's chief research information officer.

Unfortunately, the risk calculator's web page fails to explicitly identify its target audience. But there are hints that it's not for lay people such as its references to "platelets" and "chlorides."

The 19 and Me or the Nexoid risk calculators, in contrast, are both designed for use by everyone, as is a risk calculator developed by Emory University.

2. Take a Look at the Calculator's Privacy Policy

COVID-19 risk calculators ask for a lot of personal information. The Nexoid calculator, for example, wanted to know my age, weight, drug and alcohol history, pre-existing conditions, blood type and more. It even asked me about the prescription drugs I take.

It's wise to check the privacy policy and be cautious about providing an email address or other personal information. Nexoid's policy says it provides the information it gathers to researchers but it doesn't release IP addresses, which can reveal your location in certain circumstances.

John-Arne Skolbekken, a professor and risk specialist at Norwegian University of Science and Technology, entered his own data in the Nexoid calculator after being contacted by LeapsMag for comment. He noted that the calculator, among other things, asks for information about use of recreational drugs that could be illegal in some places. "I have given away some of my personal data to a company that I can hope will not misuse them," he said. "Let's hope they are trustworthy."

The 19 and Me calculator, by contrast, doesn't gather any data from users, said Cindy Hu, data scientist at Mathematica, which created it. "As soon as the window is closed, that data is gone and not captured."

The Emory University risk calculator, meanwhile, has a long privacy policy that states "the information we collect during your assessment will not be correlated with contact information if you provide it." However, it says personal information can be shared with third parties.

3. Keep an Eye on Time Horizons

Let's say a risk calculator says you have a 1 percent risk of infection. That's fairly low if we're talking about this year as a whole, but it's quite worrisome if the risk percentage refers to today and jumps by 1 percent each day going forward. That's why it's helpful to know exactly what the numbers mean in terms of time.

Unfortunately, this information isn't always readily available. You may have to dig around for it or contact a risk calculator's developers for more information. The 19 and Me calculator's risk percentages refer to this current week based on your behavior this week, Hu said. The Nexoid calculator, by contrast, has an "infinite timeline" that assumes no vaccine is developed, said Jonathon Grantham, the company's managing director. But your results will vary over time since the calculator's developers adjust it to reflect new data.

When you use a risk calculator, focus on this question: "How does your risk compare to the risk of an 'average' person?"

4. Focus on the Big Picture

The Nexoid calculator gave me numbers of 5 percent (getting COVID-19) and 99.309 percent (surviving it). It even provided betting odds for gambling types: The odds are in favor of me not getting infected (19-to-1) and not dying if I get infected (144-to-1).

However, Grantham told me that these numbers "are not the whole story." Instead, he said, "it's best to look at your risk band. This will give you a more useful insight into your personal risk." Risk bands refer to a segmentation of people into five categories, from lowest to highest risk, according to how a person's result sits relative to the whole dataset.

The Nexoid calculator says I'm in the "lowest risk band" for getting COVID-19, and a "high risk band" for dying of it if I get it. That suggests I'd better stay in the lowest-risk category because my pre-existing risk factors could spell trouble for my survival if I get infected.

Michael J. Pencina, a professor and biostatistician at Duke University School of Medicine, agreed that focusing on your general risk level is better than focusing on numbers. When you use a risk calculator, he said, focus on this question: "How does your risk compare to the risk of an 'average' person?"

The 19 and Me calculator, meanwhile, put my risk at 44 out of 100. Hu said that a score of 50 represents the typical person's risk of developing serious consequences from another disease – the flu.

5. Remember to Take Action

Hu, who helped develop the 19 and Me risk calculator, said it's best to use it to "understand the relative impact of different behaviors." As she noted, the calculator is designed to allow users to plug in different answers about their behavior and immediately see how their risk levels change.

This information can help us figure out if we should change the way we approach the world by, say, washing our hands more or avoiding more personal encounters.

"Estimation of risk is only one part of prevention," Pencina said. "The other is risk factors and our ability to reduce them." In other words, odds, percentages and risk bands can be revealing, but it's what we do to change them that matters.

Pseudoscience Is Rampant: How Not to Fall for It

A metaphorical rendering of scientific truth gone awry.

Whom to believe?

The relentless and often unpredictable coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has, among its many quirky terrors, dredged up once again the issue that will not die: science versus pseudoscience.

How does one learn to spot the con without getting a Ph.D. and spending years in a laboratory?

The scientists, experts who would be the first to admit they are not infallible, are now in danger of being drowned out by the growing chorus of pseudoscientists, conspiracy theorists, and just plain troublemakers that seem to be as symptomatic of the virus as fever and weakness.

How is the average citizen to filter this cacophony of information and misinformation posing as science alongside real science? While all that noise makes it difficult to separate the real stuff from the fakes, there is at least one positive aspect to it all.

A famous aphorism by one Charles Caleb Colton, a popular 19th-century English cleric and writer, says that "imitation is the sincerest form of flattery."

The frauds and the paranoid conspiracy mongers who would perpetrate false science on a susceptible public are at least recognizing the value of science—they imitate it. They imitate the ways in which science works and make claims as if they were scientists, because even they recognize the power of a scientific approach. They are inadvertently showing us how much we value science. Unfortunately they are just shabby counterfeits.

Separating real science from pseudoscience is not a new problem. Philosophers, politicians, scientists, and others have been worrying about this perhaps since science as we know it, a science based entirely on experiment and not opinion, arrived in the 1600s. The original charter of the British Royal Society, the first organized scientific society, stated that at their formal meetings there would be no discussion of politics, religion, or perpetual motion machines.

The first two of those for the obvious purpose of keeping the peace. But the third is interesting because at that time perpetual motion machines were one of the main offerings of the imitators, the bogus scientists who were sure that you could find ways around the universal laws of energy and make a buck on it. The motto adopted by the society was, and remains, Nullius in verba, Latin for "take nobody's word for it." Kind of an early version of Missouri's venerable state motto: "Show me."

You might think that telling phony science from the real thing wouldn't be so difficult, but events, historical and current, tell a very different story—often with tragic outcomes. Just one terrible example is the estimated 350,000 additional HIV deaths in South Africa directly caused by the now-infamous conspiracy theories of their own elected President no less (sound familiar?). It's surprisingly easy to dress up phony science as the real thing by simply adopting, or appearing to adopt, the trappings of science.

Thus, the anti-vaccine movement claims to be based on suspicion of authority, beginning with medical authority in this case, stemming from the fraudulent data published by the now-disgraced Andrew Wakefield, an English gastroenterologist. And it's true that much of science is based on suspicion of authority. Science got its start when the likes of Galileo and Copernicus claimed that the Church, the State, even Aristotle, could no longer be trusted as authoritative sources of knowledge.

But Galileo and those who followed him produced alternative explanations, and those alternatives were based on data that arose independently from many sources and generated a great deal of debate and, most importantly, could be tested by experiments that could prove them wrong. The anti-vaccine movement imitates science, still citing the discredited Wakefield report, but really offers nothing but suspicion—and that is paranoia, not science.

Similarly, there are those who try to cloak their nefarious motives in the trappings of science by claiming that they are taking the scientific posture of doubt. Science after all depends on doubt—every scientist doubts every finding they make. Every scientist knows that they can't possibly foresee all possible instances or situations in which they could be proven wrong, no matter how strong their data. Einstein was doubted for two decades, and cosmologists are still searching for experimental proofs of relativity. Science indeed progresses by doubt. In science revision is a victory.

But the imitators merely use doubt to suggest that science is not dependable and should not be used for informing policy or altering our behavior. They claim to be taking the legitimate scientific stance of doubt. Of course, they don't doubt everything, only what is problematic for their individual enterprises. They don't doubt the value of blood pressure medicine to control their hypertension. But they should, because every medicine has side effects and we don't completely understand how blood pressure is regulated and whether there may not be still better ways of controlling it.

But we use the pills we have because the science is sound even when it is not completely settled. Ask a hypertensive oil executive who would like you to believe that climate science should be ignored because there are too many uncertainties in the data, if he is willing to forgo his blood pressure medicine—because it, too, has its share of uncertainties and unwanted side effects.

The apparent success of pseudoscience is not due to gullibility on the part of the public. The problem is that science is recognized as valuable and that the imitators are unfortunately good at what they do. They take a scientific pose to gain your confidence and then distort the facts to their own purposes. How does one learn to spot the con without getting a Ph.D. and spending years in a laboratory?

"If someone claims to have the ultimate answer or that they know something for certain, the only thing for sure is that they are trying to fool you."

What can be done to make the distinction clearer? Several solutions have been tried—and seem to have failed. Radio and television shows about the latest scientific breakthroughs are a noble attempt to give the public a taste of good science, but they do nothing to help you distinguish between them and the pseudoscience being purveyed on the neighboring channel and its "scientific investigations" of haunted houses.

Similarly, attempts to inculcate what are called "scientific habits of mind" are of little practical help. These habits of mind are not so easy to adopt. They invariably require some amount of statistics and probability and much of that is counterintuitive—one of the great values of science is to help us to counter our normal biases and expectations by showing that the actual measurements may not bear them out.

Additionally, there is math—no matter how much you try to hide it, much of the language of science is math (Galileo said that). And half the audience is gone with each equation (Stephen Hawking said that). It's hard to imagine a successful program of making a non-scientifically trained public interested in adopting the rigors of scientific habits of mind. Indeed, I suspect there are some people, artists for example, who would be rightfully suspicious of changing their thinking to being habitually scientific. Many scientists are frustrated by the public's inability to think like a scientist, but in fact it is neither easy nor always desirable to do so. And it is certainly not practical.

There is a more intuitive and simpler way to tell the difference between the real thing and the cheap knock-off. In fact, it is not so much intuitive as it is counterintuitive, so it takes a little bit of mental work. But the good thing is it works almost all the time by following a simple, if as I say, counterintuitive, rule.

True science, you see, is mostly concerned with the unknown and the uncertain. If someone claims to have the ultimate answer or that they know something for certain, the only thing for sure is that they are trying to fool you. Mystery and uncertainty may not strike you right off as desirable or strong traits, but that is precisely where one finds the creative solutions that science has historically arrived at. Yes, science accumulates factual knowledge, but it is at its best when it generates new and better questions. Uncertainty is not a place of worry, but of opportunity. Progress lives at the border of the unknown.

How much would it take to alter the public perception of science to appreciate unknowns and uncertainties along with facts and conclusions? Less than you might think. In fact, we make decisions based on uncertainty every day—what to wear in case of 60 percent chance of rain—so it should not be so difficult to extend that to science, in spite of what you were taught in school about all the hard facts in those giant textbooks.

You can believe science that says there is clear evidence that takes us this far… and then we have to speculate a bit and it could go one of two or three ways—or maybe even some way we don't see yet. But like your blood pressure medicine, the stuff we know is reliable even if incomplete. It will lower your blood pressure, no matter that better treatments with fewer side effects may await us in the future.

Unsettled science is not unsound science. The honesty and humility of someone who is willing to tell you that they don't have all the answers, but they do have some thoughtful questions to pursue, are easy to distinguish from the charlatans who have ready answers or claim that nothing should be done until we are an impossible 100-percent sure.

Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery.

The problem, as we all know, is that flattery will get you nowhere.

[Editor's Note: This article was originally published on June 8th, 2020 as part of a standalone magazine called GOOD10: The Pandemic Issue. Produced as a partnership among LeapsMag, The Aspen Institute, and GOOD, the magazine is available for free online.]