How a Deadly Fire Gave Birth to Modern Medicine

The Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston in 1942 tragically claimed 490 lives, but was the catalyst for several important medical advances.

On the evening of November 28, 1942, more than 1,000 revelers from the Boston College-Holy Cross football game jammed into the Cocoanut Grove, Boston's oldest nightclub. When a spark from faulty wiring accidently ignited an artificial palm tree, the packed nightspot, which was only designed to accommodate about 500 people, was quickly engulfed in flames. In the ensuing panic, hundreds of people were trapped inside, with most exit doors locked. Bodies piled up by the only open entrance, jamming the exits, and 490 people ultimately died in the worst fire in the country in forty years.

"People couldn't get out," says Dr. Kenneth Marshall, a retired plastic surgeon in Boston and president of the Cocoanut Grove Memorial Committee. "It was a tragedy of mammoth proportions."

Within a half an hour of the start of the blaze, the Red Cross mobilized more than five hundred volunteers in what one newspaper called a "Rehearsal for Possible Blitz." The mayor of Boston imposed martial law. More than 300 victims—many of whom subsequently died--were taken to Boston City Hospital in one hour, averaging one victim every eleven seconds, while Massachusetts General Hospital admitted 114 victims in two hours. In the hospitals, 220 victims clung precariously to life, in agonizing pain from massive burns, their bodies ravaged by infection.

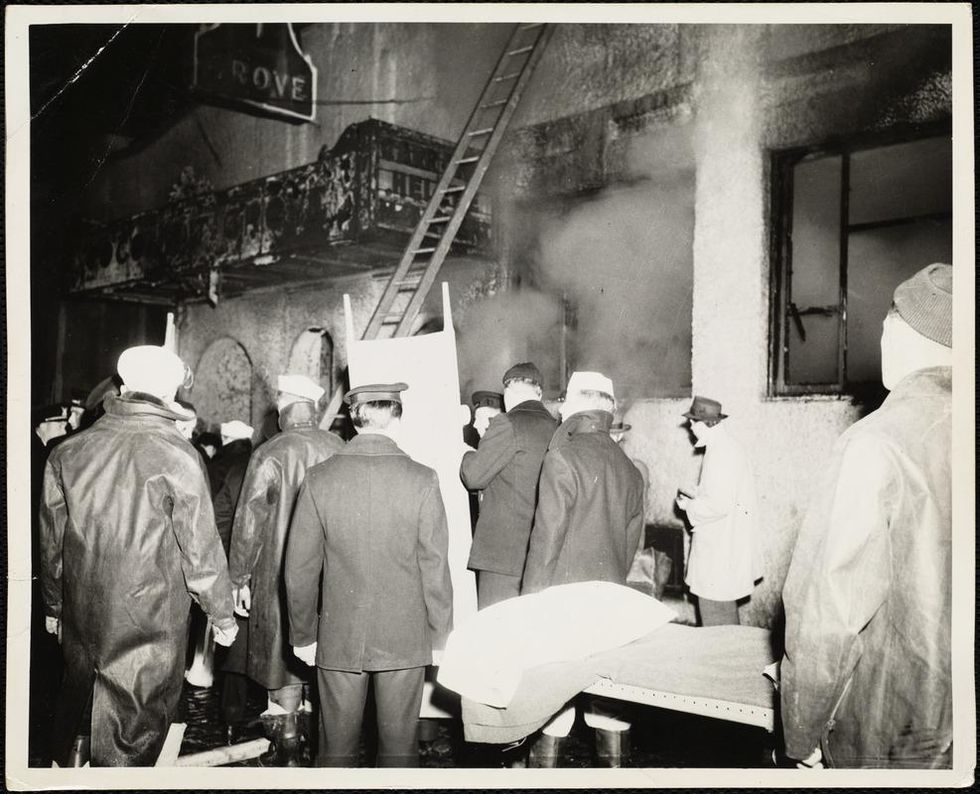

The scene of the fire.

Boston Public Library

Tragic Losses Prompted Revolutionary Leaps

But there is a silver lining: this horrific disaster prompted dramatic changes in safety regulations to prevent another catastrophe of this magnitude and led to the development of medical techniques that eventually saved millions of lives. It transformed burn care treatment and the use of plasma on burn victims, but most importantly, it introduced to the public a new wonder drug that revolutionized medicine, midwifed the birth of the modern pharmaceutical industry, and nearly doubled life expectancy, from 48 years at the turn of the 20th century to 78 years in the post-World War II years.

The devastating grief of the survivors also led to the first published study of post-traumatic stress disorder by pioneering psychiatrist Alexandra Adler, daughter of famed Viennese psychoanalyst Alfred Adler, who was a student of Freud. Dr. Adler studied the anxiety and depression that followed this catastrophe, according to the New York Times, and "later applied her findings to the treatment World War II veterans."

Dr. Ken Marshall is intimately familiar with the lingering psychological trauma of enduring such a disaster. His mother, an Irish immigrant and a nurse in the surgical wards at Boston City Hospital, was on duty that cold Thanksgiving weekend night, and didn't come home for four days. "For years afterward, she'd wake up screaming in the middle of the night," recalls Dr. Marshall, who was four years old at the time. "Seeing all those bodies lined up in neat rows across the City Hospital's parking lot, still in their evening clothes. It was always on her mind and memories of the horrors plagued her for the rest of her life."

The sheer magnitude of casualties prompted overwhelmed physicians to try experimental new procedures that were later successfully used to treat thousands of battlefield casualties. Instead of cutting off blisters and using dyes and tannic acid to treat burned tissues, which can harden the skin, they applied gauze coated with petroleum jelly. Doctors also refined the formula for using plasma--the fluid portion of blood and a medical technology that was just four years old--to replenish bodily liquids that evaporated because of the loss of the protective covering of skin.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance. And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

"The initial insult with burns is a loss of fluids and patients can die of shock," says Dr. Ken Marshall. "The scientific progress that was made by the two institutions revolutionized fluid management and topical management of burn care forever."

Still, they could not halt the staph infections that kill most burn victims—which prompted the first civilian use of a miracle elixir that was being secretly developed in government-sponsored labs and that ultimately ushered in a new age in therapeutics. Military officials quickly realized this disaster could provide an excellent natural laboratory to test the effectiveness of this drug and see if it could be used to treat the acute traumas of combat in this unfortunate civilian approximation of battlefield conditions. At the time, the very existence of this wondrous medicine—penicillin—was a closely guarded military secret.

From Forgotten Lab Experiment to Wonder Drug

In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered the curative powers of penicillin, which promised to eradicate infectious pathogens that killed millions every year. But the road to mass producing enough of the highly unstable mold was littered with seemingly unsurmountable obstacles and it remained a forgotten laboratory curiosity for over a decade. But Fleming never gave up and penicillin's eventual rescue from obscurity was a landmark in scientific history.

In 1940, a group at Oxford University, funded in part by the Rockefeller Foundation, isolated enough penicillin to test it on twenty-five mice, which had been infected with lethal doses of streptococci. Its therapeutic effects were miraculous—the untreated mice died within hours, while the treated ones played merrily in their cages, undisturbed. Subsequent tests on a handful of patients, who were brought back from the brink of death, confirmed that penicillin was indeed a wonder drug. But Britain was then being ravaged by the German Luftwaffe during the Blitz, and there were simply no resources to devote to penicillin during the Nazi onslaught.

In June of 1941, two of the Oxford researchers, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, embarked on a clandestine mission to enlist American aid. Samples of the temperamental mold were stored in their coats. By October, the Roosevelt Administration had recruited four companies—Merck, Squibb, Pfizer and Lederle—to team up in a massive, top-secret development program. Merck, which had more experience with fermentation procedures, swiftly pulled away from the pack and every milligram they produced was zealously hoarded.

After the nightclub fire, the government ordered Merck to dispatch to Boston whatever supplies of penicillin that they could spare and to refine any crude penicillin broth brewing in Merck's fermentation vats. After working in round-the-clock relays over the course of three days, on the evening of December 1st, 1942, a refrigerated truck containing thirty-two liters of injectable penicillin left Merck's Rahway, New Jersey plant. It was accompanied by a convoy of police escorts through four states before arriving in the pre-dawn hours at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dozens of people were rescued from near-certain death in the first public demonstration of the powers of the antibiotic, and the existence of penicillin could no longer be kept secret from inquisitive reporters and an exultant public. The next day, the Boston Globe called it "priceless" and Time magazine dubbed it a "wonder drug."

Within fourteen months, penicillin production escalated exponentially, churning out enough to save the lives of thousands of soldiers, including many from the Normandy invasion. And in October 1945, just weeks after the Japanese surrender ended World War II, Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain were awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine. But penicillin didn't just save lives—it helped build some of the most innovative medical and scientific companies in history, including Merck, Pfizer, Glaxo and Sandoz.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance," concludes Marshall. "And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

Researchers Are Discovering How to Predict – and Maybe Treat — Pregnancy Complications Early On.

Katie Love cradles her newborn daughter, born after a bout with preeclampsia.

Katie Love wishes there was some way she could have been prepared. But there was no way to know, early in 2020, that her pregnancy would lead to terrifyingly high blood pressure and multiple hospital visits, ending in induced labor and a 56-hour-long, “nightmare” delivery at 37 weeks. Love, a social media strategist in Pittsburgh, had preeclampsia, a poorly understood and potentially deadly pregnancy complication that affects 1 in 25 pregnant women in the United States. But there was no blood test, no easy diagnostic marker to warn Love that this might happen. Even on her first visit to the emergency room, with sky-high blood pressure, doctors could not be certain preeclampsia was the cause.

In fact, the primary but imperfect indicators for preeclampsia — high blood pressure and protein in the urine — haven’t changed in decades. The Preeclampsia Foundation calls a simple, rapid test to predict or diagnose the condition “a key component needed in the fight.”

Another common pregnancy complication is preterm birth, which affects 1 in 10 U.S. pregnancies, but there are few options to predict that might happen, either.

“The best tool that obstetricians have at the moment is still a tape measure and a blood pressure cuff to diagnose whatever’s happening in your pregnancy,” says Fiona Kaper, a vice president at the DNA-sequencing company Illumina in San Diego.

The hunt for such specific biomarkers is now taking off, at Illumina and elsewhere, as scientists probe maternal blood for signs that could herald pregnancy problems. These same molecules offer clues that might lead to more specific treatments. So far, it’s clear that many complications start with the placenta, the temporary organ that transfers nutrients, oxygen and waste between mother and fetus, and that these problems often start well before symptoms arise. Researchers are using the latest stem-cell technology to better understand the causes of complications and test treatments.

Pressing Need

Obstetricians aren’t flying completely blind; medical history can point to high or low risk for pregnancy complications. But ultimately, “everybody who’s pregnant is at risk for preeclampsia,” says Sarosh Rana, chief of maternal-fetal medicine at University of Chicago Medicine and an advisor to the Preeclampsia Foundation. And the symptoms of the condition include problems like headache and swollen feet that overlap with those of pregnancy in general, complicating diagnoses.

The “holy grail" would be early, first-trimester biomarkers. If obstetricians and expecting parents could know, in the first few months of pregnancy, that preeclampsia is a risk, a pregnant woman could monitor her blood pressure at home and take-low dose aspirin that might stave it off.

There are a couple more direct tests physicians can turn to, but these are imperfect. For preterm labor, fetal fibronectin makes up a sort of glue that keeps the amniotic sac, which cushions the unborn baby, attached to the uterus. If it’s not present near a woman’s cervix, that’s a good indicator that she’s not in labor, and can be safely sent home, says Lauren Demosthenes, an obstetrician and senior medical director of the digital health company Babyscripts in Washington, D.C. But if fibronectin appears, it might or might not indicate preterm labor.

“What we want is a test that gives us a positive predictive [signal],” says Demosthenes. “I want to know, if I get it, is it really going to predict preterm birth, or is it just going to make us worry more and order more tests?” In fact, the fetal fibronectin test hasn’t been shown to improve pregnancy outcomes, and Demosthenes says it’s fallen out of favor in many clinics.

Similarly, there’s a blood test, based on the ratio of the amounts of two different proteins, that can rule out preeclampsia but not confirm it’s happening. It’s approved in many countries, though not the U.S.; studies are still ongoing. A positive test, which means “maybe preeclampsia,” still leaves doctors and parents-to-be facing excruciating decisions: If the mother’s life is in danger, delivering the baby can save her, but even a few more days in the uterus can promote the baby’s health. In Ireland, where the test is available, it’s not getting much use, says Patricia Maguire, director of the University College Dublin Institute for Discovery.

Maguire has identified proteins released by platelets that indicate pregnancy — the “most expensive pregnancy test in the world,” she jokes. She is now testing those markers in women with suspected preeclampsia.

The “holy grail,” says Maguire, would be early, first-trimester biomarkers. If obstetricians and expecting parents could know, in the first few months of pregnancy, that preeclampsia is a risk, a pregnant woman could monitor her blood pressure at home and take-low dose aspirin that might stave it off. Similarly, if a quick blood test indicated that preterm labor could happen, doctors could take further steps such as measuring the cervix and prescribing progesterone if it’s on the short side.

Biomarkers in Blood

It was fatherhood that drew Stephen Quake, a biophysicist at Stanford University in California, to the study of pregnancy biomarkers. His wife, pregnant with their first child in 2001, had a test called amniocentesis. That involves extracting a sample from within the uterus, using a 3–8-inch-long needle, for genetic testing. The test can identify genetic differences, such as Down syndrome, but also carries risks including miscarriage or infection. In this case, mom and baby were fine (Quake’s daughter is now a college student), but he found the diagnostic danger unacceptable.

Seeking a less invasive test, Quake in 2008 reported that there’s enough fetal DNA in the maternal bloodstream to diagnose Down syndrome and other genetic conditions. “Use of amniocentesis has plunged,” he says.

Then, recalling that his daughter was born three and a half weeks before her due date — and that Quake’s own mom claims he was a month late, which makes him think the due date must have been off — he started researching markers that could accurately assess a fetus’ age and predict the timing of labor. In this case, Quake was interested in RNA, not DNA, because it’s a signal of which genes the fetus’, placenta’s, and mother’s tissues are using to create proteins. Specifically, these are RNAs that have exited the cells that made them. Tissues can use such free RNAs as messages, wrapping them in membranous envelopes to travel the bloodstream to other body parts. Dying cells also release fragments containing RNAs. “A lot of information is in there,” says Kaper.

In a small study of 31 healthy pregnant women, published in 2018, Quake and collaborators discovered nine RNAs that could predict gestational age, which indicates due date, just as well as ultrasound. With another set of 38 women, including 13 who delivered early, the researchers discovered seven RNAs that predicted preterm labor up to two months in advance.

Quake notes that an RNA-based blood test is cheaper and more portable than ultrasound, so it might be useful in the developing world. A company he cofounded, Mirvie, Inc., is now analyzing RNA’s predictive value further, in thousands of diverse women. CEO and cofounder Maneesh Jain says that since preterm labor is so poorly understood, they’re sequencing RNAs that represent about 20,000 genes — essentially all the genes humans have — to find the very best biomarkers. “We don’t know enough about this field to guess what it might be,” he says. “We feel we’ve got to cast the net wide.”

Quake, and Mirvie, are now working on biomarkers for preeclampsia. In a recent preprint study, not yet reviewed by other experts, Quake’s Stanford team reported 18 RNAs that, measured before 16 weeks, correctly predicted preeclampsia 56–100% of the time.

Other researchers are taking a similar tack. Kaper’s team at Illumina was able to classify preeclampsia from bloodstream RNAs with 85 to 89% accuracy, though they didn’t attempt to predict it. And Louise Laurent, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist and researcher at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has defined several pairs of microRNAs — pint-sized RNAs that regulate other ones — in second-trimester blood samples that predict preeclampsia later on.

Placentas in a Dish

The RNAs that show up in these studies often come from genes used by the placenta. But they’re only signals that something’s wrong, not necessarily the root cause. “There still is not much known about what really causes major complications of pregnancy,” says Laurent.

The challenge is that placental problems likely occur early on, as the organ forms in the first trimester. For example, if the placenta did a poor job of building blood vessels through the uterine lining, it might cause preeclampsia later as the growing fetus tries to access more and more blood through insufficient vessels, leading to high blood pressure in the mother. “Everyone has kind of suspected that that is probably what goes wrong,” says Mana Parast, a pathologist and researcher at UCSD.

To see how a placenta first faltered, “you want to go back in time,” says Parast. It’s only recently become possible to do something akin to that: She and Laurent take cells from the umbilical cord (which is a genetic match for the placenta) at the end of pregnancy, and turn them into stem cells, which can become any kind of cell. They then nudge those stem cells to make new placenta cells in lab dishes. But when the researchers start with cells from an umbilical cord after preeclampsia, they find the stem cells struggle to even form proper placenta cells, or they develop abnormally. So yes, something seems to go wrong right at the beginning. Now, the team plans to use these cell cultures to study the microRNAs that indicate preeclampsia risk, and to look for medications that might reverse the problems, Parast says.

Biomarkers could lead to treatments. For example, one of the proteins that commercial preeclampsia diagnostic kits test for is called soluble Flt-1. It’s a sort of anti-growth factor, explains Rana, that can cause problems with blood vessels and thus high blood pressure. Getting rid of the extra Flt-1, then, might alleviate symptoms and keep the mother safe, giving the baby more time to develop. Indeed, a small trial that filtered this protein from the blood did lower blood pressure, allowing participants to keep their babies inside for a couple of weeks longer, researchers reported in 2011.

For pregnant women like Love, even advance warning would have been beneficial. Laurent and others envision a first-trimester blood test that would use different kinds of biomolecules — RNAs, proteins, whatever works best — to indicate whether a pregnancy is at low, medium, or high risk for common complications.

“I prefer to be prepared,” says Love, now the mother of a healthy little girl. “I just wouldn’t have been so thrown off by the whole thing.”

Dec. 17th Event: The Latest on Omicron, Boosters, and Immunity

The Omicron variant poses new uncertainty for the vaccines, which four leading experts will address during our virtual event on December 17th, 2021.

This virtual event will convene leading scientific and medical experts to discuss the most pressing questions around the new Omicron variant, including what we know so far about its ability to evade COVID-19 vaccines, the role of boosters in eliciting heightened immunity, and the science behind variants and vaccines. A public Q&A will follow the expert discussion.

EVENT INFORMATION:

Date: Friday Dec 17, 2021

2:00pm - 3:30pm EST

Dr. Céline Gounder, MD, ScM, is the CEO/President/Founder of Just Human Productions, a non-profit multimedia organization. She is also the host and producer of American Diagnosis, a podcast on health and social justice, and Epidemic, a podcast about infectious disease epidemics and pandemics. She served on the Biden-Harris Transition COVID-19 Advisory Board.

Dr. Theodora Hatziioannou, Ph.D., is a Research Associate Professor in the Laboratory of Retrovirology at The Rockefeller University. Her research includes identifying plasma samples from recovered COVID-19 patients that contain antibodies capable of neutralizing the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus.

Dr. Theodora Hatziioannou, Ph.D., is a Research Associate Professor in the Laboratory of Retrovirology at The Rockefeller University. Her research includes identifying plasma samples from recovered COVID-19 patients that contain antibodies capable of neutralizing the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus.

Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu, MBBCh, is an Associate Professor at Yale School of Medicine and an infectious disease specialist who treats COVID-19 patients and leads Yale’s clinical studies around COVID-19. He ran Yale’s trial of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

Dr. Eric Topol, M.D., is a cardiologist, scientist, professor of molecular medicine, and the director and founder of Scripps Research Translational Institute. He has led clinical trials in over 40 countries with over 200,000 patients and pioneered the development of many routinely used medications.

This event is the fourth of a four-part series co-hosted by Leaps.org, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.