How a Deadly Fire Gave Birth to Modern Medicine

The Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston in 1942 tragically claimed 490 lives, but was the catalyst for several important medical advances.

On the evening of November 28, 1942, more than 1,000 revelers from the Boston College-Holy Cross football game jammed into the Cocoanut Grove, Boston's oldest nightclub. When a spark from faulty wiring accidently ignited an artificial palm tree, the packed nightspot, which was only designed to accommodate about 500 people, was quickly engulfed in flames. In the ensuing panic, hundreds of people were trapped inside, with most exit doors locked. Bodies piled up by the only open entrance, jamming the exits, and 490 people ultimately died in the worst fire in the country in forty years.

"People couldn't get out," says Dr. Kenneth Marshall, a retired plastic surgeon in Boston and president of the Cocoanut Grove Memorial Committee. "It was a tragedy of mammoth proportions."

Within a half an hour of the start of the blaze, the Red Cross mobilized more than five hundred volunteers in what one newspaper called a "Rehearsal for Possible Blitz." The mayor of Boston imposed martial law. More than 300 victims—many of whom subsequently died--were taken to Boston City Hospital in one hour, averaging one victim every eleven seconds, while Massachusetts General Hospital admitted 114 victims in two hours. In the hospitals, 220 victims clung precariously to life, in agonizing pain from massive burns, their bodies ravaged by infection.

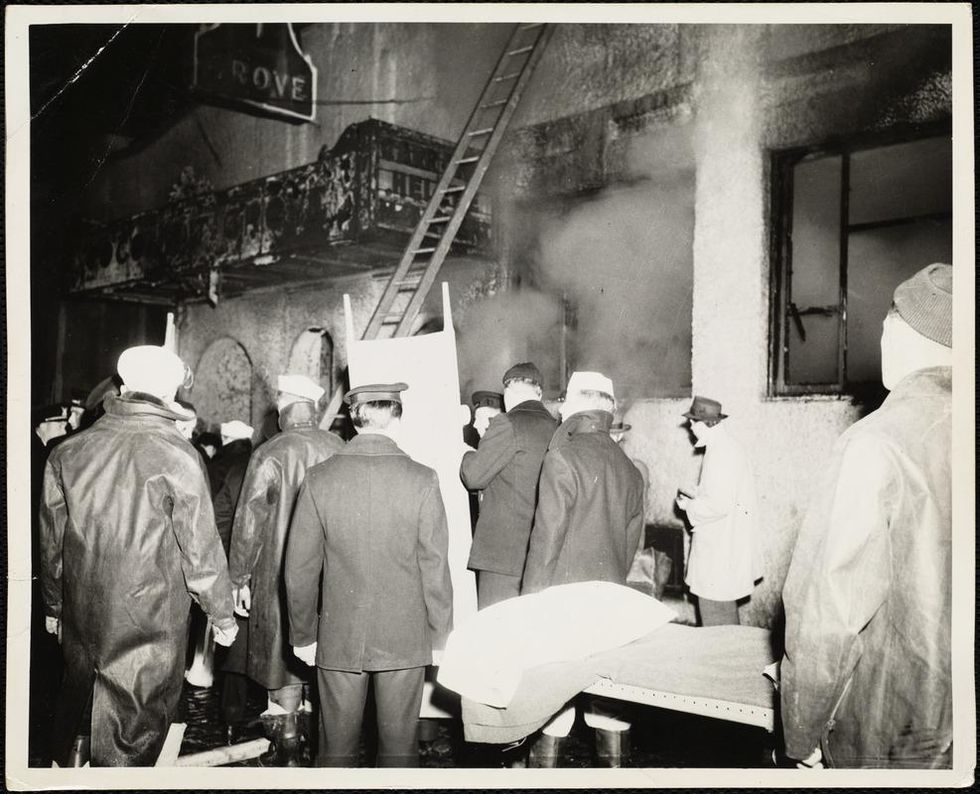

The scene of the fire.

Boston Public Library

Tragic Losses Prompted Revolutionary Leaps

But there is a silver lining: this horrific disaster prompted dramatic changes in safety regulations to prevent another catastrophe of this magnitude and led to the development of medical techniques that eventually saved millions of lives. It transformed burn care treatment and the use of plasma on burn victims, but most importantly, it introduced to the public a new wonder drug that revolutionized medicine, midwifed the birth of the modern pharmaceutical industry, and nearly doubled life expectancy, from 48 years at the turn of the 20th century to 78 years in the post-World War II years.

The devastating grief of the survivors also led to the first published study of post-traumatic stress disorder by pioneering psychiatrist Alexandra Adler, daughter of famed Viennese psychoanalyst Alfred Adler, who was a student of Freud. Dr. Adler studied the anxiety and depression that followed this catastrophe, according to the New York Times, and "later applied her findings to the treatment World War II veterans."

Dr. Ken Marshall is intimately familiar with the lingering psychological trauma of enduring such a disaster. His mother, an Irish immigrant and a nurse in the surgical wards at Boston City Hospital, was on duty that cold Thanksgiving weekend night, and didn't come home for four days. "For years afterward, she'd wake up screaming in the middle of the night," recalls Dr. Marshall, who was four years old at the time. "Seeing all those bodies lined up in neat rows across the City Hospital's parking lot, still in their evening clothes. It was always on her mind and memories of the horrors plagued her for the rest of her life."

The sheer magnitude of casualties prompted overwhelmed physicians to try experimental new procedures that were later successfully used to treat thousands of battlefield casualties. Instead of cutting off blisters and using dyes and tannic acid to treat burned tissues, which can harden the skin, they applied gauze coated with petroleum jelly. Doctors also refined the formula for using plasma--the fluid portion of blood and a medical technology that was just four years old--to replenish bodily liquids that evaporated because of the loss of the protective covering of skin.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance. And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

"The initial insult with burns is a loss of fluids and patients can die of shock," says Dr. Ken Marshall. "The scientific progress that was made by the two institutions revolutionized fluid management and topical management of burn care forever."

Still, they could not halt the staph infections that kill most burn victims—which prompted the first civilian use of a miracle elixir that was being secretly developed in government-sponsored labs and that ultimately ushered in a new age in therapeutics. Military officials quickly realized this disaster could provide an excellent natural laboratory to test the effectiveness of this drug and see if it could be used to treat the acute traumas of combat in this unfortunate civilian approximation of battlefield conditions. At the time, the very existence of this wondrous medicine—penicillin—was a closely guarded military secret.

From Forgotten Lab Experiment to Wonder Drug

In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered the curative powers of penicillin, which promised to eradicate infectious pathogens that killed millions every year. But the road to mass producing enough of the highly unstable mold was littered with seemingly unsurmountable obstacles and it remained a forgotten laboratory curiosity for over a decade. But Fleming never gave up and penicillin's eventual rescue from obscurity was a landmark in scientific history.

In 1940, a group at Oxford University, funded in part by the Rockefeller Foundation, isolated enough penicillin to test it on twenty-five mice, which had been infected with lethal doses of streptococci. Its therapeutic effects were miraculous—the untreated mice died within hours, while the treated ones played merrily in their cages, undisturbed. Subsequent tests on a handful of patients, who were brought back from the brink of death, confirmed that penicillin was indeed a wonder drug. But Britain was then being ravaged by the German Luftwaffe during the Blitz, and there were simply no resources to devote to penicillin during the Nazi onslaught.

In June of 1941, two of the Oxford researchers, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, embarked on a clandestine mission to enlist American aid. Samples of the temperamental mold were stored in their coats. By October, the Roosevelt Administration had recruited four companies—Merck, Squibb, Pfizer and Lederle—to team up in a massive, top-secret development program. Merck, which had more experience with fermentation procedures, swiftly pulled away from the pack and every milligram they produced was zealously hoarded.

After the nightclub fire, the government ordered Merck to dispatch to Boston whatever supplies of penicillin that they could spare and to refine any crude penicillin broth brewing in Merck's fermentation vats. After working in round-the-clock relays over the course of three days, on the evening of December 1st, 1942, a refrigerated truck containing thirty-two liters of injectable penicillin left Merck's Rahway, New Jersey plant. It was accompanied by a convoy of police escorts through four states before arriving in the pre-dawn hours at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dozens of people were rescued from near-certain death in the first public demonstration of the powers of the antibiotic, and the existence of penicillin could no longer be kept secret from inquisitive reporters and an exultant public. The next day, the Boston Globe called it "priceless" and Time magazine dubbed it a "wonder drug."

Within fourteen months, penicillin production escalated exponentially, churning out enough to save the lives of thousands of soldiers, including many from the Normandy invasion. And in October 1945, just weeks after the Japanese surrender ended World War II, Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain were awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine. But penicillin didn't just save lives—it helped build some of the most innovative medical and scientific companies in history, including Merck, Pfizer, Glaxo and Sandoz.

"Every war has given us a new medical advance," concludes Marshall. "And penicillin was the great scientific advance of World War II."

Friday Five Podcast: New drug may slow the rate of Alzheimer's disease

On September 27, pharmaceuticals Biogen and Eisai announced that their drug, lecanemab, can slow the rate of Alzheimer's disease, according to a clinical trial. Today's Friday Five episode covers this story and other health research over the month of September.

The Friday Five covers important stories in health and science research that you may have missed - usually over the previous week, but today's episode is a lookback on important studies over the month of September.

Most recently, on September 27, pharmaceuticals Biogen and Eisai announced that a clinical trial showed their drug, lecanemab, can slow the rate of Alzheimer's disease. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend and the new month.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

This Friday Five episode covers the following studies published and announced over the past month:

- A new drug is shown to slow the rate of Alzheimer's disease

- The need for speed if you want to reduce your risk of dementia

- How to refreeze the north and south poles

- Ancient wisdom about Neti pots could pay off for Covid

- Two women, one man and a baby

Could epigenetic reprogramming reverse aging?

A range of strategies are being explored to reprogram the body's cells to an earlier state. Most scientists aren't betting on a new fountain of youth just yet - but, in theory, epigenetic reprogramming is a recipe for self-renewal.

Ten thousand years ago, the average human spent a maximum of 30 years on Earth. Despite the glory of Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, most of their inhabitants didn’t surpass the age of 35. Between the 1500s and 1800, life expectancy (at least in Europe) fluctuated between 30 and 40 years.

Public health advancements like control of infectious diseases, better diet and clean sanitation, as well as social improvements have made it possible for human lifespans to double since 1800. Although lifespan differs widely today from country to country according to socioeconomic health, the average has soared to 73.2 years.

But this may turn out to be on the low side if epigenetic rejuvenation fulfills its great promise: to reverse aging, perhaps even completely. Epigenetic rejuvenation, or partial reprogramming, is the process by which a set of therapies are trying to manipulate epigenetics – how various changes can affect our genes – and the Yamanaka factors. These Yamanaka factors are a group of proteins that can convert any cell of the body into pluripotent stem cells, a group of cells that can turn into brand new cells, such as those of the brain or skin. At least in theory, it could be a recipe for self-renewal.

“Partial reprogramming tries to knock a few years off of people’s biological age, while preserving their original cell identity and function,” says Yuri Deigin, cofounder and director of YouthBio Therapeutics, a longevity startup utilizing partial reprogramming to develop gene therapies aimed at the renewal of epigenetic profiles. YouthBio plans to experiment with injecting these gene therapies into target organs. Once the cargo is delivered, a specific small molecule will trigger gene expression and rejuvenate those organs.

“Our ultimate mission is to find the minimal number of tissues we would need to target to achieve significant systemic rejuvenation,” Deigin says. Initially, YouthBio will apply these therapies to treat age-related conditions. Down the road, though, their goal is for everyone to get younger. “We want to use them for prophylaxis, which is rejuvenation that would lower disease risk,” Deigin says.

Epigenetics has swept the realm of biology off its feet over the last decade. We now know that we can switch genes on and off by tweaking the chemical status quo of the DNA’s local environment. "Epigenetics is a fascinating and important phenomenon in biology,’’ says Henry Greely, a bioethicist at Stanford Law School. Greely is quick to stress that this kind of modulation (turning genes on and off and not the entire DNA) happens all the time. “When you eat and your blood sugar goes up, the gene in the beta cells of your pancreas that makes insulin is turned on or up. Almost all medications are going to have effects on epigenetics, but so will things like exercise, food, and sunshine.”

Can intentional control over epigenetic mechanisms lead to novel and useful therapies? “It is a very plausible scenario,” Greely says, though a great deal of basic research into epigenetics is required before it becomes a well-trodden way to stay healthy or treat disease. Whether these therapies could cause older cells to become younger in ways that have observable effects is “far from clear,” he says. “Historically, betting on someone’s new ‘fountain of youth’ has been a losing strategy.”

The road to de-differentiation, the process by which cells return to an earlier state, is not paved with roses; de-differentiate too much and you may cause pathology and even death.

In 2003 researchers finished sequencing the roughly 3 billion letters of DNA that make up the human genome. The human genome sequencing was hailed as a vast step ahead in our understanding of how genetics contribute to diseases like cancer or to developmental disorders. But for Josephine Johnston, director of research and research scholar at the Hastings Center, the hype has not lived up to its initial promise. “Other than some quite effective tests to diagnose certain genetic conditions, there isn't a radical intervention that reverses things yet,” Johnston says. For her, this is a testament to the complexity of biology or at least to our tendency to keep underestimating it. And when it comes to epigenetics specifically, Johnston believes there are some hard questions we need to answer before we can safely administer relevant therapies to the population.

“You'd need to do longitudinal studies. You can't do a study and look at someone and say they’re safe only six months later,” Johnston says. You can’t know long-term side effects this way, and how will companies position their therapies on the market? Are we talking about interventions that target health problems, or life enhancements? “If you describe something as a medical intervention, it is more likely to be socially acceptable, to attract funding from governments and ensure medical insurance, and to become a legitimate part of medicine,” she says.

Johnston’s greatest concerns are of the philosophical and ethical nature. If we’re able to use epigenetic reprogramming to double the human lifespan, how much of the planet’s resources will we take up during this long journey? She believes we have a moral obligation to make room for future generations. “We should also be honest about who's actually going to afford such interventions; they would be extraordinarily expensive and only available to certain people, and those are the people who would get to live longer, healthier lives, and the rest of us wouldn't.”

That said, Johnston agrees there is a place for epigenetic reprogramming. It could help people with diseases that are caused by epigenetic problems such as Fragile X syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome and various cancers.

Zinaida Good, a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford Cancer Institute, says these problems are still far in the future. Any change will be incremental. “Thinking realistically, there’s not going to be a very large increase in lifespan anytime soon,” she says. “I would not expect something completely drastic to be invented in the next 5 to 10 years. ”

Good won’t get any such treatment for herself until it’s shown to be effective and safe. Nature has programmed our bodies to resist hacking, she says, in ways that could undermine any initial benefits to longevity. A preprint that is not yet peer-reviewed reports cellular reprogramming may lead to premature death due to liver and intestinal problems, and using the Yamanaka factors may have the potential to cause cancer, at least in animal studies.

“Side effects are an open research question that all partial reprogramming companies and labs are trying to address,” says Deigin. The road to de-differentiation, the process by which cells return to an earlier state, is not paved with roses; de-differentiate too much and you may cause pathology and even death. Deigin is exploring other, less risky approaches. “One way is to look for novel factors tailored toward rejuvenation rather than de-differentiation.” Unlike Yamanaka factors, such novel factors would never involve taking a given cell to a state in which it could turn cancerous, according to Deigin.

An example of a novel factor that could lower the risk of cancer is artificially introducing mRNA molecules, or molecules carrying the genetic information necessary to make proteins, by using electricity to penetrate the cell instead of a virus. There is also chemical-based reprogramming, in which chemicals are applied to convert regular cells into pluripotent cells. This approach is currently effective only for mice though.

“The search for novel factors tailored toward rejuvenation without de-differentiation is an ongoing research and development effort by several longevity companies, including ours,” says Deigin.

He isn't disclosing the details of his own company’s underlying approach to lowering the risk, but he’s hopeful that something will eventually end up working in humans. Yet another challenge is that, partly because of the uncertainties, the FDA hasn’t seen fit to approve a single longevity therapy. But with the longevity market projected to soar to $600 billion by 2025, Deigin says naysayers are clinging irrationally to the status quo. “Thankfully, scientific progress is moved forward by those who bet for something while disregarding the skeptics - who, in the end, are usually proven wrong.”