A surprising weapon in the fight against food poisoning

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

Phages, which are harmless viruses that destroy specific bacteria, are becoming useful tools to protect our food supply.

Every year, one in seven people in America comes down with a foodborne illness, typically caused by a bacterial pathogen, including E.Coli, listeria, salmonella, or campylobacter. That adds up to 48 million people, of which 120,000 are hospitalized and 3000 die, according to the Centers for Disease Control. And the variety of foods that can be contaminated with bacterial pathogens is growing too. In the 20th century, E.Coli and listeria lurked primarily within meat. Now they find their way into lettuce, spinach, and other leafy greens, causing periodic consumer scares and product recalls. Onions are the most recent suspected culprit of a nationwide salmonella outbreak.

Some of these incidents are almost inevitable because of how Mother Nature works, explains Divya Jaroni, associate professor of animal and food sciences at Oklahoma State University. These common foodborne pathogens come from the cattle's intestines when the animals shed them in their manure—and then they get washed into rivers and lakes, especially in heavy rains. When this water is later used to irrigate produce farms, the bugs end up on salad greens. Plus, many small farms do both—herd cattle and grow produce.

"Unfortunately for us, these pathogens are part of the microflora of the cows' intestinal tract," Jaroni says. "Some farmers may have an acre or two of cattle pastures, and an acre of a produce farm nearby, so it's easy for this water to contaminate the crops."

Food producers and packagers fight bacteria by potent chemicals, with chlorine being the go-to disinfectant. Cattle carcasses, for example, are typically washed by chlorine solutions as the animals' intestines are removed. Leafy greens are bathed in water with added chlorine solutions. However, because the same "bath" can be used for multiple veggie batches and chlorine evaporates over time, the later rounds may not kill all of the bacteria, sparing some. The natural and organic producers avoid chlorine, substituting it with lactic acid, a more holistic sanitizer, but even with all these efforts, some pathogens survive, sickening consumers and causing food recalls. As we farm more animals and grow more produce, while also striving to use fewer chemicals and more organic growing methods, it will be harder to control bacteria's spread.

"It took us a long time to convince the FDA phages were safe and efficient alternatives. But we had worked with them to gather all the data they needed, and the FDA was very supportive in the end."

Luckily, bacteria have their own killers. Called bacteriophages, or phages for short, they are viruses that prey on bacteria only. Under the electron microscope, they look like fantasy spaceships, with oblong bodies, spider-like legs and long tails. Much smaller than a bacterium, phages pierce the microbes' cells with their tails, sneak in and begin multiplying inside, eventually bursting the microbes open—and then proceed to infect more of them.

The best part is that these phages are harmless to humans. Moreover, recent research finds that millions of phages dwell on us and in us—in our nose, throat, skin and gut, protecting us from bacterial infections as part of our healthy microbiome. A recent study suggested that we absorb about 30 billion phages into our bodies on a daily basis. Now, ingeniously, they are starting to be deployed as anti-microbial agents in the food industry.

A Maryland-based phage research company called Intralytix is doing just that. Founded by Alexander Sulakvelidze, a microbiologist and epidemiologist who came to the United States from Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, Intralytix makes and sells five different FDA-approved phage cocktails that work against some of the most notorious food pathogens: ListShield for Listeria, SalmoFresh for Salmonella, ShigaShield for Shigella, another foodborne bug, and EcoShield for E.coli, including the infamous strain that caused the Jack in the Box outbreak in 1993 that killed four children and sickened 732 people across four states. Last year, the FDA granted its approval to yet another Intralytix phage for managing Campylobacter contamination, named CampyShield. "We call it safety by nature," Sulakvelidze says.

Intralytix grows phages inside massive 1500-liter fermenters, feeding them bacterial "fodder."

Photo credit: Living Radiant Photography

Phage preparations are relatively straightforward to make. In nature, phages thrive in any body of water where bacteria live too, including rivers, lakes and bays. "I can dip a bucket into the Chesapeake Bay, and it will be full of all kinds of phages," Sulakvelidze says. "Sewage is another great place to look for specific phages of interest, because it's teeming with all sorts of bacteria—and therefore the viruses that prey on them."

In lab settings, Intralytix grows phages inside massive 1500-liter fermenters, feeding them bacterial "fodder." Once phages multiply enough, they are harvested, dispensed into containers and shipped to food producers who have adopted this disinfecting practice into their preparation process. Typically, it's done by computer-controlled sprayer systems that disperse mist-like phage preparations onto the food.

Unlike chemicals like chlorine or antibiotics, which kill a wide spectrum of bacteria, phages are more specialized, each feeding on specific microbial species. A phage that targets salmonella will not prey on listeria and vice versa. So food producers may sometimes use a combo of different phage preparations. Intralytix is continuously researching and testing new phages. With a contract from the National Institutes of Health, Intralytix is expanding its automated high-throughput robot that tests which phages work best against which bacteria, speeding up the development of the new phage cocktails.

Phages have other "talents." In her recent study, Jaroni found that phages have the ability to destroy bacterial biofilms—colonies of microorganisms that tend to grow on surfaces of the food processing equipment, surrounding themselves with protective coating that even very harsh chemicals can't crack.

"Phages are very clever," Jaroni says. "They produce enzymes that target the biofilms, and once they break through, they can reach the bacteria."

Convincing the FDA that phages were safe to use on food products was no easy feat, Sulakvelidze says. In his home country of Georgia, phages have been used as antimicrobial remedies for over a century, but the FDA was leery of using viruses as food safety agents. "It took us a long time to convince the FDA phages were safe and efficient alternatives," Sulakvelidze says. "But we had worked with them to gather all the data they needed, and the FDA was very supportive in the end."

The agency had granted Intralytix its first approval in 2006, and over the past 10 years, the company's sales increased by over 15-fold. "We currently sell to about 40 companies and are in discussions with several other large food producers," Sulakvelidze says. One indicator that the industry now understands and appreciates the science of phages was that his company was ranked as Top Food Safety Provider in 2021 by Food and Beverage Technology Review, he adds. Notably, phage sprays are kosher, halal and organic-certified.

Intralytix's phage cocktails to safeguard food from bacteria are approved for consumers in addition to food producers, but currently the company sells to food producers only. Selling retail requires different packaging like easy-to-use spray bottles and different marketing that would inform people about phages' antimicrobial qualities. But ultimately, giving people the ability to remove pathogens from their food with probiotic phage sprays is the goal, Sulakvelidze says.

It's not the company's only goal. Now Intralytix is going a step further, investigating phages' probiotic and therapeutic abilities. Because phages are highly specialized in the bacteria they target, they can be used to treat infections caused by specific pathogens while leaving the beneficial species of our microbiome intact. In an ongoing clinical trial with Mount Sinai, Intralytix is now investigating a potential phage treatment against a certain type of E. coli for patients with Crohn's disease, and is about to start another clinical trial for treating bacterial dysentery.

"Now that we have proved that phages are safe and effective against foodborne bacteria," Sulakvelidze says, "we are going to demonstrate their potential in therapeutic applications."

This article was first published by Leaps.org on October 27, 2021.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

Tech-related injuries are becoming more common as many people depend on - and often develop addictions for - smart phones and computers.

In the 1990s, a mysterious virus spread throughout the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Artificial Intelligence Lab—or that’s what the scientists who worked there thought. More of them rubbed their aching forearms and massaged their cricked necks as new computers were introduced to the AI Lab on a floor-by-floor basis. They realized their musculoskeletal issues coincided with the arrival of these new computers—some of which were mounted high up on lab benches in awkward positions—and the hours spent typing on them.

Today, these injuries have become more common in a society awash with smart devices, sleek computers, and other gadgets. And we don’t just get hurt from typing on desktop computers; we’re massaging our sore wrists from hours of texting and Facetiming on phones, especially as they get bigger in size.

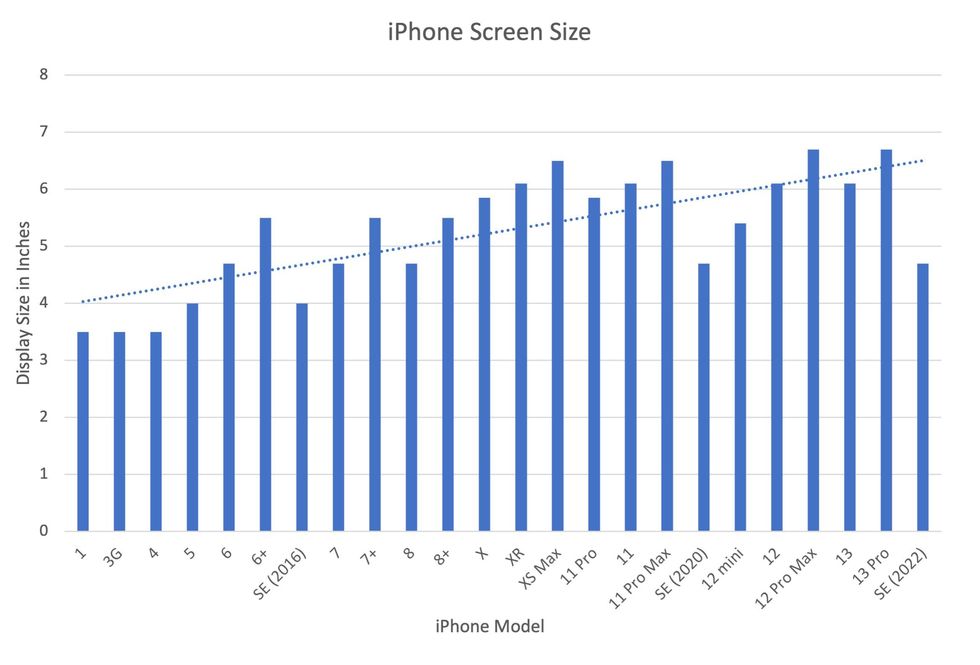

In 2007, the first iPhone measured 3.5-inches diagonally, a measurement known as the display size. That’s been nearly doubled by the newest iPhone 13 Pro, which has a 6.7-inch display. Other phones, too, like the Google Pixel 6 and the Samsung Galaxy S22, have bigger screens than their predecessors. Physical therapists and orthopedic surgeons have had to come up with names for a variety of new conditions: selfie elbow, tech neck, texting thumb. Orthopedic surgeon Sonya Sloan says she sees selfie elbow in younger kids and in women more often than men. She hears complaints related to technology once or twice a day.

The addictive quality of smartphones and social media means that people spend more time on their devices, which exacerbates injuries. According to Statista, 68 percent of those surveyed spent over three hours a day on their phone, and almost half spent five to six hours a day. Another report showed that people dedicate a third of their day to checking their phones, while the Media Effects Research Laboratory at Pennsylvania State University has found that bigger screens, ideal for entertainment purposes, immerse their users more than smaller screens. Oversized screens also provide easier navigation and more space for those with bigger hands or trouble seeing.

But others with conditions like arthritis can benefit from smaller phones. In March of 2016, Apple released the iPhone SE with a display size of 4.7 inches—an inch smaller than the iPhone 7, released that September. Apple has since come out with two more versions of the diminutive iPhone SE, one in 2020 and another in 2022.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance science journalist, has the Google Pixel 6. She was drawn to the phone because Google marketed the Pixel 6’s camera as better at capturing different skin tones. But this phone boasts one of the largest display sizes on the market: 6.4 inches.

Senapathy was diagnosed with carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes in 2017 and fibromyalgia in 2019. She has had to create a curated ergonomic workplace setup, otherwise her wrists and hands get weak and tingly, and she’s had to adjust how she holds her phone to prevent pain flares.

Recently, Senapathy underwent an electromyography, or an EMG, in which doctors insert electrodes into muscles to measure their electrical activity. The electrical response of the muscles tells doctors whether the nerve cells and muscles are successfully communicating. Depending on her results, steroid shots and even surgery might be required. Senapathy wants to stick with her Pixel 6, but the pain she’s experiencing may push her to buy a smaller phone. Unfortunately, options for these modestly sized phones are more limited.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers like Senapathy to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable for creating addictive devices that lead to musculoskeletal injury?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance journalist, bought the Google Pixel 6 because of its high-quality camera, but she’s had to adjust how she holds the oversized phone to prevent pain flares.

Kavin Senapathy

A one-size-fits-all mentality for smartphones will continue to lead to injuries because every user has different wants and needs. S. Shyam Sundar, the founder of Penn State’s lab on media effects and a communications professor, says the needs for mobility and portability conflict with the desire for greater visibility. “The best thing a company can do is offer different sizes,” he says.

Joanna Bryson, an AI ethics expert and professor at The Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, Germany, echoed these sentiments. “A lot of the lack of choice we see comes from the fact that the markets have consolidated so much,” she says. “We want to make sure there’s sufficient diversity [of products].”

Consumers can still maintain some control despite the ubiquity of tech. Sloan, the orthopedic surgeon, has to pester her son to change his body positioning when using his tablet. Our heads get heavier as they bend forward: at rest, they weigh 12 pounds, but bent 60 degrees, they weigh 60. “I have to tell him, ‘Raise your head, son!’” she says. It’s important, Sloan explains, to consider that growth and development will affect ligaments and bones in the neck, potentially making kids even more vulnerable to injuries from misusing gadgets. She recommends that parents limit their kids’ tech time to alleviate strain. She also suggested that tech companies implement a timer to remind us to change our body positioning.

In 2017, Nan-Wei Gong, a former contractor for Google, founded Figur8, which uses wearable trackers to measure muscle function and joint movement. It’s like physical therapy with biofeedback. “Each unique injury has a different biomarker,” says Gong. “With Figur8, you are comparing yourself to yourself.” This allows an individual to self-monitor for wear and tear and strengthen an injury in a way that’s efficient and designed for their body. Gong noticed that the work-from-home model during the COVID-19 pandemic created a new set of ergonomic problems that resulted in injuries. Figur8 provides real-time data for these injuries because “behavioral change requires feedback.”

Gong worked on a project called Jacquard while at Google. Textile experts weave conductive thread into their fabric, and the result is a patch of the fabric—like the cuff of a Levi’s jacket—that responds to commands on your smartphone. One swipe can call your partner or check the weather. It was designed with cyclists in mind who can’t easily check their phones, and it’s part of a growing movement in the tech industry to deliver creative, hands-free design. Gong thinks that engineers at large corporations like Google have accessibility in mind; it’s part of what drives their decisions for new products.

Display sizes of iPhones have become larger over time.

Sourced from Screenrant https://screenrant.com/iphone-apple-release-chronological-order-smartphone/ and Apple Tech Specs: https://www.apple.com/iphone-se/specs/

Back in Germany, Joanna Bryson reminds us that products like smartphones should adhere to best practices. These rules may be especially important for phones and other products with AI that are addictive. Disclosure, accountability, and regulation are important for AI, she says. “The correct balance will keep changing. But we have responsibilities and obligations to each other.” She was on an AI Ethics Council at Google, but the committee was disbanded after only one week due to issues with one of their members.

Bryson was upset about the Council’s dissolution but has faith that other regulatory bodies will prevail. OECD.AI, and international nonprofit, has drafted policies to regulate AI, which countries can sign and implement. “As of July 2021, 46 governments have adhered to the AI principles,” their website reads.

Sundar, the media effects professor, also directs Penn State’s Center for Socially Responsible AI. He says that inclusivity is a crucial aspect of social responsibility and how devices using AI are designed. “We have to go beyond first designing technologies and then making them accessible,” he says. “Instead, we should be considering the issues potentially faced by all different kinds of users before even designing them.”

Entomologist Jessica Ware is using new technologies to identify insect species in a changing climate. She shares her suggestions for how we can live harmoniously with creeper crawlers everywhere.

Jessica Ware is obsessed with bugs.

My guest today is a leading researcher on insects, the president of the Entomological Society of America and a curator at the American Museum of Natural History. Learn more about her here.

You may not think that insects and human health go hand-in-hand, but as Jessica makes clear, they’re closely related. A lot of people care about their health, and the health of other creatures on the planet, and the health of the planet itself, but researchers like Jessica are studying another thing we should be focusing on even more: how these seemingly separate areas are deeply entwined. (This is the theme of an upcoming event hosted by Leaps.org and the Aspen Institute.)

Listen to the Episode

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Entomologist Jessica Ware

D. Finnin / AMNH

Maybe it feels like a core human instinct to demonize bugs as gross. We seem to try to eradicate them in every way possible, whether that’s with poison, or getting out our blood thirst by stomping them whenever they creep and crawl into sight.

But where did our fear of bugs really come from? Jessica makes a compelling case that a lot of it is cultural, rather than in-born, and we should be following the lead of other cultures that have learned to live with and appreciate bugs.

The truth is that a healthy planet depends on insects. You may feel stung by that news if you hate bugs. Reality bites.

Jessica and I talk about whether learning to live with insects should include eating them and gene editing them so they don’t transmit viruses. She also tells me about her important research into using genomic tools to track bugs in the wild to figure out why and how we’ve lost 50 percent of the insect population since 1970 according to some estimates – bad news because the ecosystems that make up the planet heavily depend on insects. Jessica is leading the way to better understand what’s causing these declines in order to start reversing these trends to save the insects and to save ourselves.